Ferdinand Weber (German, 1715–1784). Square piano, 1772. Dublin, Ireland. Mahogany, iron, brass, ivory, ebony, various materials. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Bequest of Murtogh D. Guinness, 2003 (2003.300)

«Dublin had a flourishing music scene in the eighteenth century. The city had two cathedrals, St. Patrick's and Christ Church, that both employed a retinue of full-time professional musicians. In addition, a state orchestra was also maintained to provide music for civic occasions. Musicians were attracted to Dublin for these positions and found ample additional opportunities for music making in the numerous concert halls and theaters across the city. Dublin even attracted George Frederick Handel, who visited in 1741 and 1742, and premiered the Messiah there on April 13, 1742.»

This vibrant music scene fostered a highly active market for the sale of musical instruments, which understandably appealed to instrument makers. One such maker was the German keyboard builder Ferdinand Weber, who would become recognized as the most important keyboard maker active in Ireland in the eighteenth century. Weber was born in Borstendorf, Saxony, in 1715, and apprenticed with the organ maker Johann Ernst Hähnel. Before arriving in Dublin, in 1749, Weber is known to have been active in London for several years earlier in that decade. In Dublin, he built organs for several of the city's churches, though none of the instruments survive intact, and to maintain and tune the organs of Christ Church Cathedral and Trinity College. Weber also built stringed keyboard instruments including harpsichords, spinets, and at least one clavicytherium (upright harpsichord) that still exist, but a square piano at The Metropolitan Museum of Art is the only instrument of its type that survives from his workshop.

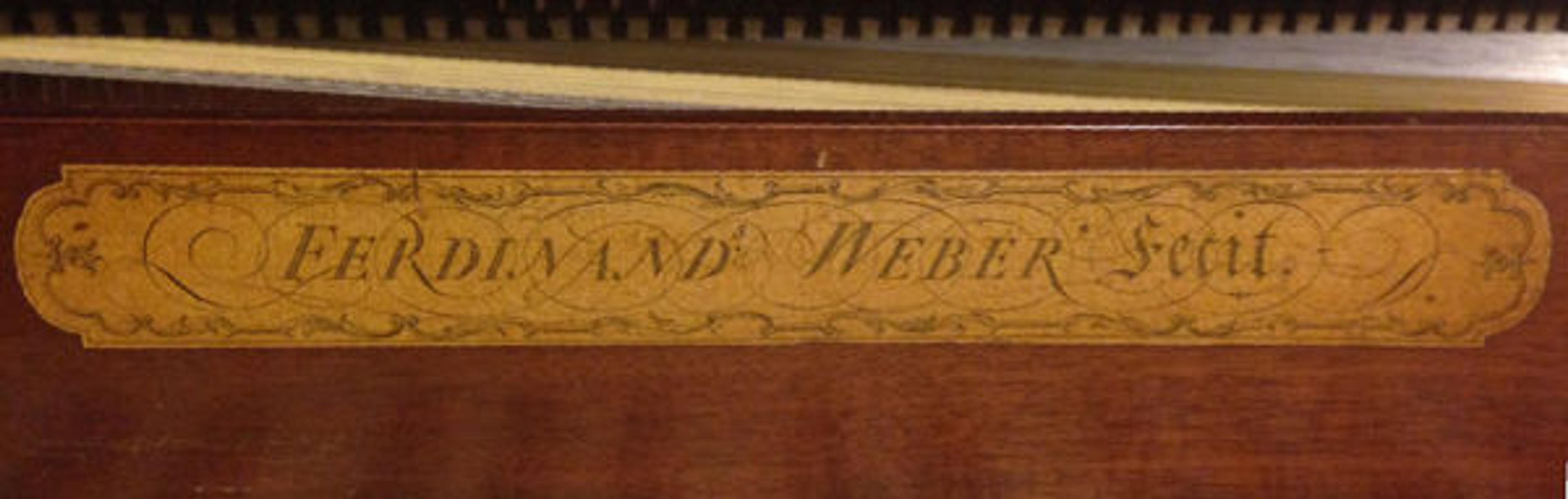

The piano's name board. Photo courtesy of the author

The square piano was a small instrument, actually rectangular in shape, invented by Johannes Zumpe, in London, in 1766. Its size and affordability made it a good instrument for home use, especially in the apartments and houses of the growing middle class to whom the instrument was marketed. Zumpe's instruments were championed by Johann Christian Bach (the tenth child of Johann Sebastian Bach), who helped popularize the square piano model.

Dated 1772, only a few years after the square piano was invented, the Met's instrument by Ferdinand Weber shows several rather remarkable and innovative ideas. Although its size and appearance—a mahogany case and fifty-nine keys (spanning the range of GG to f3) with ivory-covered naturals and ebony-block accidentals—are typical for the time, the instrument sits on two collapsible legs that allow the instrument to be folded up for easy transportation or storage.

Detail view of the piano's hammer heads. Photo courtesy of the author

The most interesting feature of this piano is that it has two hammers for each note on the keyboard. The main playing hammers have wooden heads wrapped in a thin layer of leather, while a second set of hammers with heads made of buff leather are used to create a softer volume and sweeter timbre. The player can switch from the hard hammers to the soft ones by pulling out a brass-knobbed hand stop located inside the piano case, to the left of the keyboard. Engaging the knob shifts all of the hammers slightly to position the soft hammers into alignment with the keys and strings. It is an ingenious mechanism. A second hand stop removes the dampers, allowing the strings to vibrate longer after they are struck and create a more sustained sound. Two foot pedals, one mounted to each leg, were added at a later point and connect to the hand stops.

This remarkable piano was given to the Museum by Murtogh D. Guinness, a member of the prominent Irish beer-making family.

Follow Jayson on Twitter: @JayKerrDobney

Related Link

Of Note: Celebrating National Piano Month at the Met