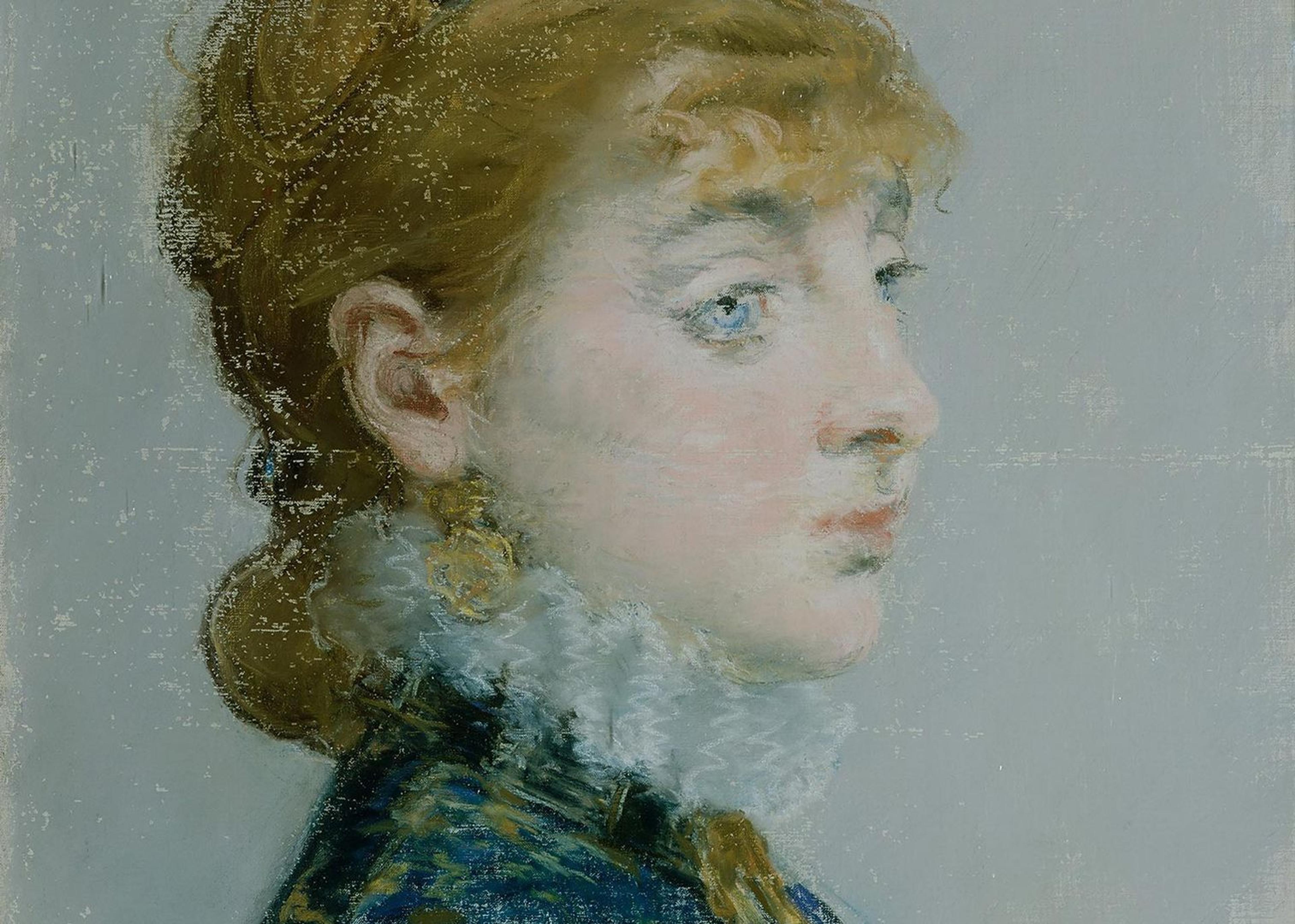

When we among the staff talk about missing The Met in this period of quarantine, my mind often turns to such small jewels of the collection as Edouard Manet’s Emilie-Louise Delabigne (1848–1910), Called Valtesse de la Bigne. A technical tour de force in which minimal swathes, dabs, and squiggles of pastel on canvas form the bust of one of the most notorious beautiful young women in late nineteenth-century Paris, Manet’s Valtesse is both a wondrous object and a record of one of Paris’s high-class courtesans. Yes, that’s right, this stunning portrait depicts a prostitute. Delabigne also seems to have had something of a personal relationship with the artist late in his life. Manet completed this work just four years before he died of syphilis at age fifty-one in 1883.

Born Emilie-Louise Delabigne, and aged thirty-one in Manet’s portrait, the sitter had grown up quickly after working in a dress shop at age thirteen and being sexually assaulted by an older man. She followed her mother into the sex trade as a young grisette, all the while admiring the lifestyle of the high-class call girls (grandes horizontales) who were often kept in fancy apartments and given fashionable clothes and jewelry. After bearing two children to a man who refused to marry her, she focused on her social ambition, leaving her two young daughters to be raised by their grandmother.

Soon, she became a chorus girl at the popular Bouffes-Parisiens, where she chose the stage name “Valtesse,” a contraction of “Votre Altesse” (Your Highness). She became the mistress of Jacques Offenbach, the composer and founder of the Bouffes-Parisiens, and appeared as Hebe in his Orpheus of the Underworld. From his circle, she moved on after the Franco-Prussian War to consort with Prince Lubomirski of Poland, who showered her with dresses, hats, jewels, and even a large new residence. Dropping him for the next ritzy suitor, the Valtesse changed her name from “Delabigne” to “de la Bigne” to imply aristocratic origins. (The name was associated with one of the oldest noble families in Normandy, the province from which the Valtesse originally came.) She even dubbed herself “Comtesse” (Countess) and had the painter Edouard Detaille (another client-suitor) paint portraits of her fictional noble ancestors. She embraced blue as her signature color to match her large pale blue eyes and adopted the nickname “Rayon d’or” (ray of gold), in reference to her gold-toned red hair. Manet was careful to capture her in a celestial blue that complements her eyes and contrasts with her porcelain skin and her trademark golden-red hair.

In her later days, she attended opening nights at the opera, was waited on by servants, and lived in a Parisian hôtel particulieron the Boulevard Malesherbes, a gift from the Prince de Sagan. There, she greeted her male guests in a lavish gilt bronze and wooden state bed adorned with two flaming incense burners and a headboard featuring two cupids bearing a shield with the crowned letter “V” and masks of leering fauns smiling down upon the proceedings. The bed was designed especially for her by Edouard Lièvre in 1875, just four years before The Met’s portrait; you can visit it today—or, let’s hope, very soon—in the Musée des Arts Décoratifs in Paris.

Edouard Lièvre (1828–1886). State bed of Valtesse de la Bigne, ca. 1875. Paris. Carcase of wood, gilt bronze, green silk velvet. Paris, Musée des Arts Décoratifs. Bequest of Emilie-Louise de la Bigne, known as Valtesse de la Bigne, 1911. © MAD, Paris

Her bedroom (and, some say, she herself) became the inspiration for Emile Zola’s novel Nana, first published serially the same year as Manet’s portrait. She also is said to have consorted with artists beyond Manet, including Gustave Courbet, Eugène Boudin, and Henri Gervex, whose fashionable portrait of her in a garden with a parasol appeared at the Salon of 1879, a year before Manet’s pastel. (Gervex also included her as the very self-possessed courtesan who looks directly out at the viewer in his large The Civil Marriage [1880–81, Salle des Mariages, Mairie of the 19th arrondissement, Paris].) Male artists appreciated her for her quick wit and conversation as much as for her beauty. In 1876, she wrote a mostly autobiographical novel under the pseudonym “Ego” called Isola, in which a striking redhead like herself falls into prostitution after being assaulted.

Later in life, she sold her Paris and Monte Carlo homes and retired to the suburb of Ville d’Avray to teach young courtesans-to-be the ways of the world. Upon her death in 1910, she bequeathed her bed and portraits to French museums with the stipulation that they be exhibited with plaques identifying their source as the “Valtesse de la Bigne.” The Met’s great patrons the Havemeyers had already purchased Manet’s pastel at an auction of her vast art collection in 1902.

Left: Edouard Manet (French, 1832–1883). Mademoiselle Isabelle Lemonnier (1857–1926), 1879–82. Pastel on canvas, 22 x 18 1/4 in. (55.9 x 46.4 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, H. O. Havemeyer Collection, Bequest of Mrs. H. O. Havemeyer, 1929 (29.100.56)

The Valtesse’s body, her road map to social and financial success, has been purposely omitted from Manet’s portrait. He treats her face as the equivalent of that of his young crush, the respectable, high-born Isabelle Lemonnier, also presented in the same three-quarter bust format in pastel. (The work is on view in the same room at The Met and created in the same period.) Lemonnier was the younger sister of the influential saloniste Marguerite Lemonnier Charpentier, wife of the publisher Georges Charpentier and subject of Renoir’s famous portrait (also at The Met) in which she is accompanied by her two children and her dog seated in her salon. Manet’s choice to omit (or, at least, completely cover up) the body of a prostitute honors her, raising her status to the higher social realms to which she strove to enter; the subject was, in fact, partial to high-collared dresses for this reason. (By contrast, Manet actually reveals Lemonnier’s décolletage in her bust-length portrait.) It is no wonder that the Valtesse was thrilled with the portrait and wrote the artist to thank him profusely, even though the portrait had been his idea. When Manet asked her permission to exhibit this pastel at the Salon of 1880, for all of high society to see, she replied, “Gladly, and with all my heart; both for you and for me.”

Manet’s blue, golden red, and rosy peach-filled pastel portrait betrays a debt to the French eighteenth-century pastel portrait tradition best elucidated by the likes of Maurice Quentin de la Tour, Jean-Baptiste Perronneau, and Jean Etienne Liotard. The three-quarter profile format recalls many eighteenth-century pastel “tête” subjects as well as miniatures of high-born female subjects. Finally, the Valtesse’s light powdered complexion and eighteenth-century revival-style white lace ruff—simply conveyed by zigzagging white squiggles on a light gray base—and her high-buttoned tight-bodiced blue dress, too, all elevate her image in their bow to earlier eighteenth-century styles; this revival dress style was the latest fashion in 1879. Her gold earrings, too, convey her posh image. Meanwhile, the artist was careful to capture every wisp of her hair, every eyelash—even those clumped with powder—and her signature celestial blue eyes. I’ve spent a long time looking at the Valtesse over the years, and I hope you will again soon, too.

Edouard Manet (French, 1832–1883). Emilie-Louise Delabigne (1848–1910), Called Valtesse de la Bigne (detail), 1879. Pastel on canvas, 21 3/4 x 14 in. (55.2 x 35.6 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, H. O. Havemeyer Collection, Bequest of Mrs. H. O. Havemeyer, 1929 (29.100.561)

Over and over, The Met is filled with such moments where we gasp in awe at the seemingly impossibly detailed technique with which a work has been made. Often, as with Manet’s Valtesse, we learn the improbable history behind the object as it is illuminated and contextualized in the label and wall chat, or through The Met’s many guides, educators, and audio guides. As we float from room to room in the galleries, we find all manner of magical connections to be made. It is a world of wonder, and we miss it so. May we all return to its splendors soon enough.