Hanukkah lamp, 1866–72. Polish, Lviv (Lwów, Lvov, or Lemberg). Silver: cast, chased and engraved, 33 9/16 x 23 1/8 in., 60 lb. (85.3 x 58.7 cm, 27.2 kg). On loan from The Moldovan Family Collection

With its great splash of silver, this Hanukkah menorah (or hanukkiya) proclaims a time of celebration: The Festival of Lights. Since 2014, The Met has welcomed Hanukkah by displaying this refined work of art from the Moldovan Family Collection. Standing nearly three feet tall, it dazzles. Each of its eight silver branches is in flower; blossoms tumble from its stalk and irrepressibly burst forth at the top. At its center, a great eagle, wings outstretched, is poised to take flight, while seated lions proudly support the entire sixty-pound piece on their backs. This remarkable piece is currently on view in Gallery 554.

Hanukkah is more than a time for children’s songs and chocolates. It is a metaphor for the very survival of the Jewish faith. The holiday celebrates the end of a dark time, millennia ago, when Judaism was outlawed and the Temple of Jerusalem was deliberately profaned, desecrated by a conquering empire. Like all such lamps, this one was created for the symbolic reenactment of an ancient miracle, in which a single day’s worth of sacred oil in the Temple lasted for eight. This Hanukkah menorah bears witness to all that the holiday signifies, in sobering, profound ways that the silversmith who created it could never have foreseen.

Stamped into the silver on the Moldovan lamp are marks that localize it to mid-nineteenth-century Lviv, in present-day Ukraine. (The city is known as Lemberg in German and Lwów in Polish.) There, a Hanukkah menorah of the same remarkable type, likely modeled on a famous seventeenth-century brass example from the same city was photographed in the Great Suburban Synagogue in 1909. As in other eastern European synagogues, the Hanukkah menorah stood to the south of the Torah ark, an allusion to the position of the Menorah in the Tabernacle and the Temple of Jerusalem. The hanukkiya in the photograph corresponds to the Moldovan lamp in every detail but one: the silver lamp on loan to The Met never had a shammash, or supporting arm for a ninth candle that serves to light the others.

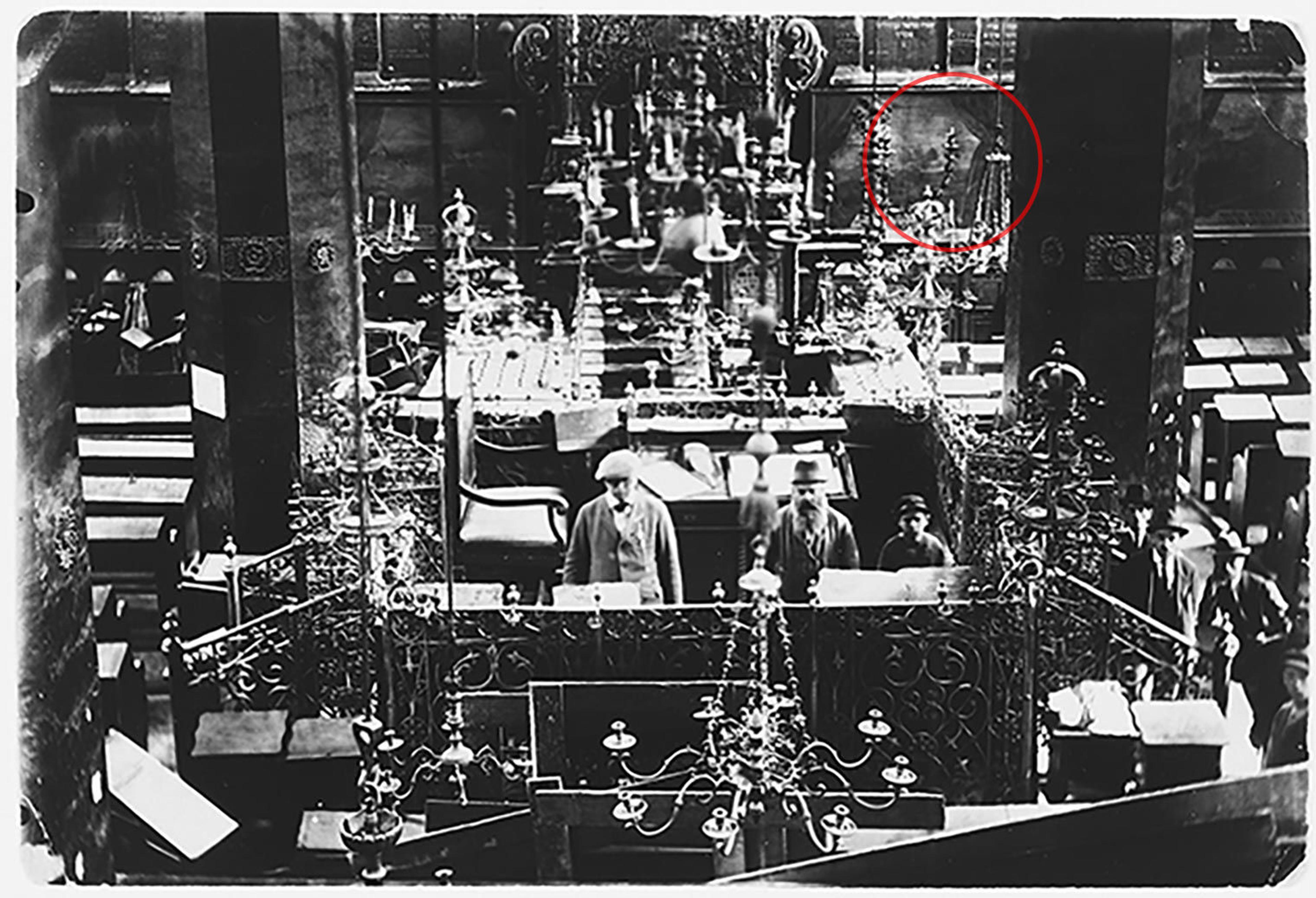

The hanukkiya is just visible in the upper right of this photo of a visiting Jewish-American in the Great Suburban Synagogue in Lwów, Poland, 1921. Photo by Minosa © United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, Paul (Leopold) Lustig (2005.76)

The merest glimpse of the Lviv synagogue’s hanukkiya is visible in a 1921 photo of a Brooklyn tourist, born near Lemberg, taking part in a service. Curiously, however, when Lviv’s Committee for the Protection of Jewish Art Monuments listed the contents of the city’s synagogues four years later, no Hanukkah menorah was listed among the twenty-four objects in the Great Suburban Synagogue. Yet the hanukiyyah was still in place in the photo they commissioned that year.

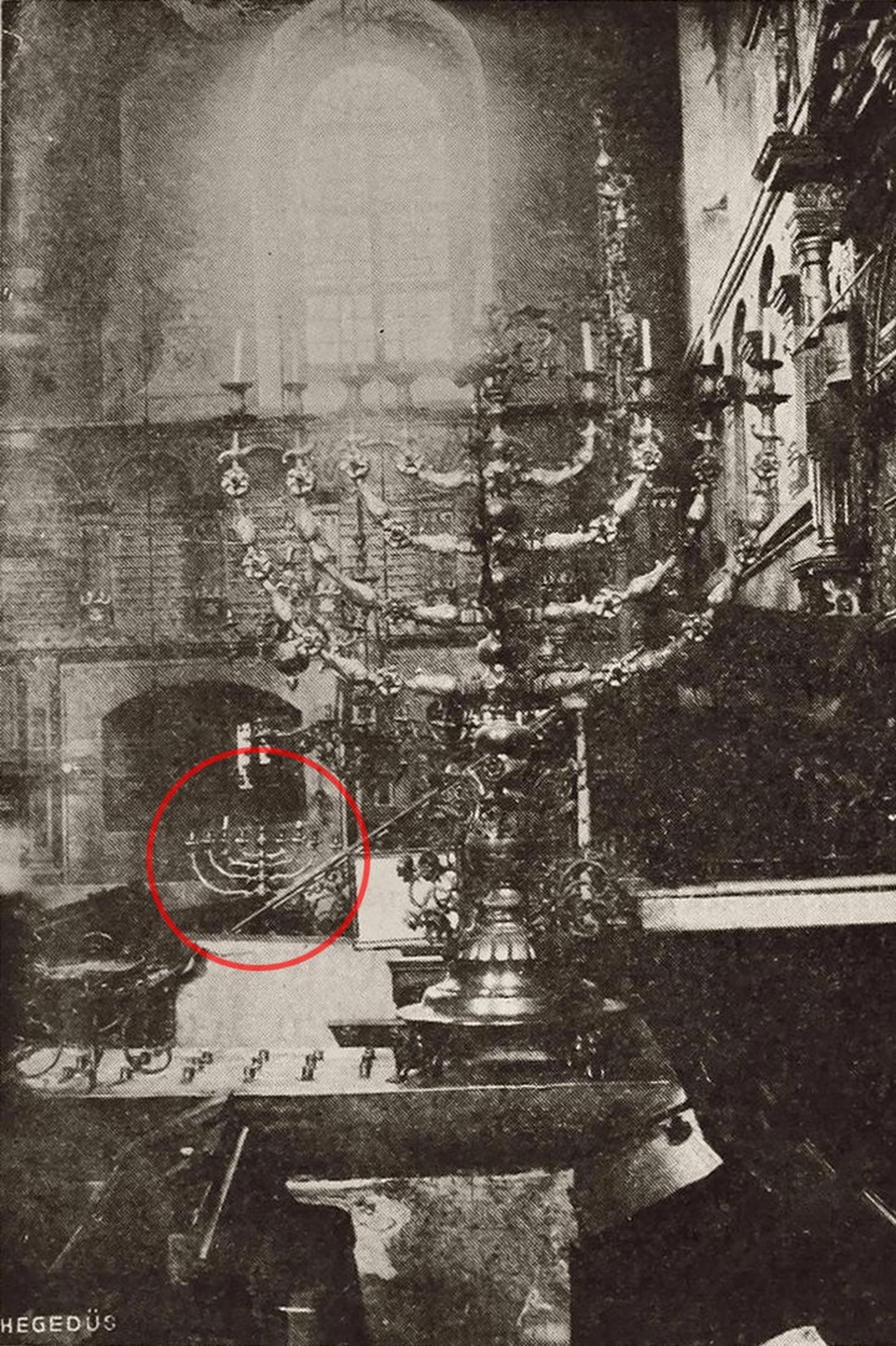

Two eight-branch candelabra are visible in this 1909 photo of the interior of the Great Suburban Synagogue, Lviv. Reproduction from Majer Bałaban, Dzielnica żydowska we Lwowie, jej dzieje i zabytki [Jewish quarter in Lviv: Its history and monuments] (Lviv: Towarzystwo miłośników przeszłości Lwowa, 1909), 89. Public-domain image courtesy Wikimedia Commons

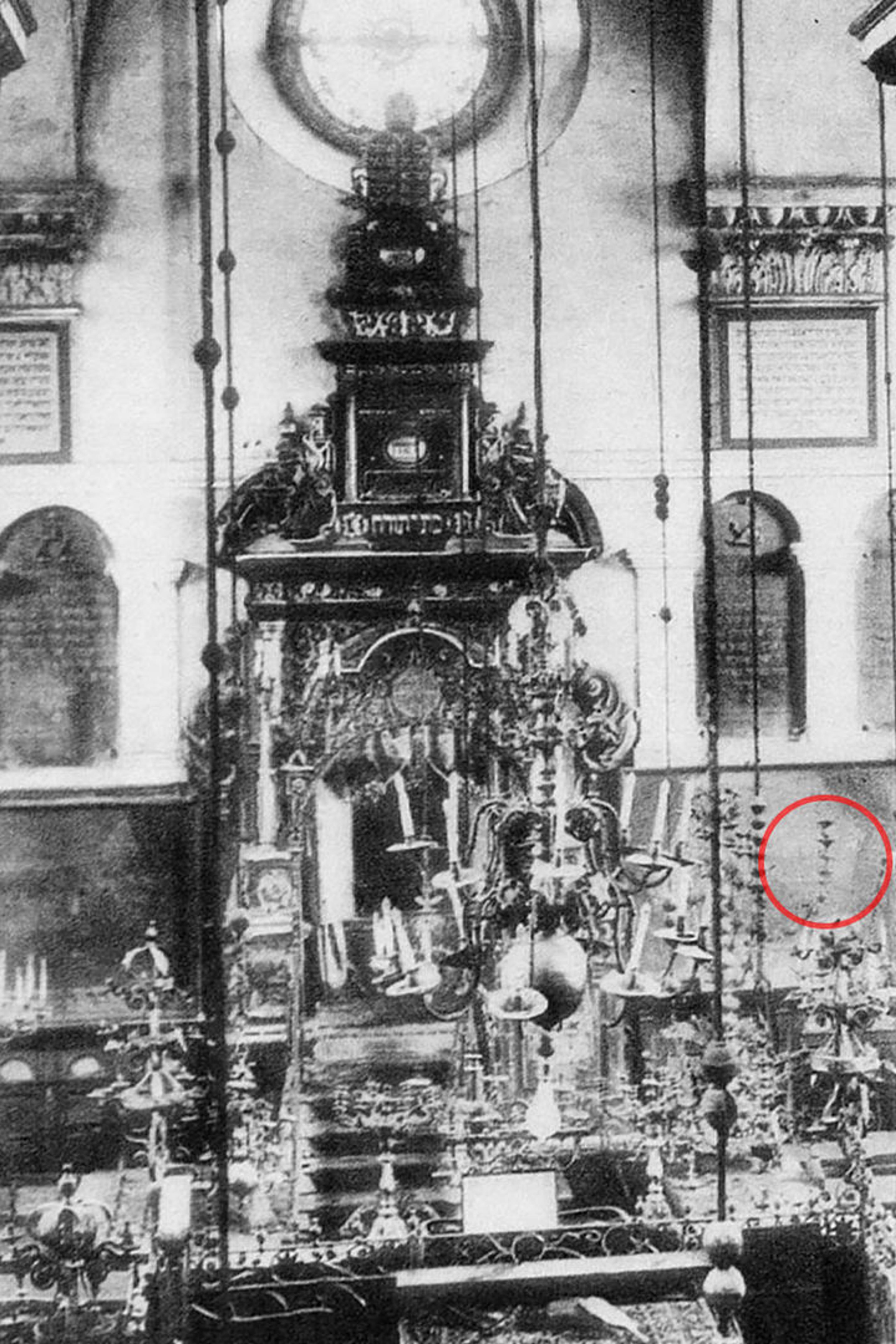

The hanukkiya is visible in the right of this 1932 photo. Reproduction from Chwila [Moment], illustrated supplement, no 40, vol. 3, October 2, 1932, p. 2. Photograph by Juliusz Mehrer (1908–1942). Image courtesy Archives of Ukrainian Periodicals Online

The lamp retains its place in the synagogue in a 1932 photo, its shammash peeking out at the right. Three years later, a Jewish guidebook mentioned not one but “two beautiful seven-branched [sic] chandeliers on either side of the ark” in the Great Suburban Synagogue. With that information, and looking very closely, we can dimly perceive that there is a second hanukkiya in the background of the 1909 photo. But is it the same type? That is not clear.

Large silver Hanukkah menorot were always the exception; most were brass. But Lviv had been a vibrant, prosperous city for centuries, a center of trade, learning, and culture. Its merchants were linked to Vienna, Krakow, and Prague to the west, and Russia and the Ottoman Empire to the east. The Jewish community boasted an exceptional number of gold- and silversmiths, and their work filled the synagogues.

Damage to the Great Suburban Synagogue, Lwów, during Nazi occupation. Images courtesy Bildarchiv Austria

Persecution of the city’s Jewish population came in sporadic waves. They trace as early as the fourteenth century, and extended into the twentieth. While they varied in intensity, they were consistent in malevolence. Civilization came crashing down altogether in 1939. First the Soviets occupied Lemberg, then the Nazis, beginning June 30, 1941. That year, the Nazis badly damaged the Great Suburban Synagogue.

It was still standing, in a crumbling state, in June 1943 when the Nazis completed their relentless, systematic campaign to murder the Jews in Lemberg, of whom there had been nearly 130,000 at the beginning of the occupation. The final destruction of the synagogue followed that same summer.

Hanukkah lamp, 1867–72. Lemberg (Lviv, Ukraine). Silver: cast, engraved, and traced, 34 1/4 x 23 7/8 x 15 in. (87 x 60.7 x 38.1 cm). The Jewish Museum, Gift of Dr. Harry G. Friedman in memory of Adele Friedman (F 5119)

The hanukkiya visible in the historic photographs of the Great Suburban Synagogue seems to me, and to colleagues in Israel who helped trace this lamp’s history, to have escaped somehow. We believe it to be the same as one that is now in the Jewish Museum.

It appeared, seemingly out of nowhere in Vienna in 1960. Where had it been? Had a member of Lemberg’s Jewish community, foreseeing the horrors on the horizon, dismantled it and then hidden it until the war ended?

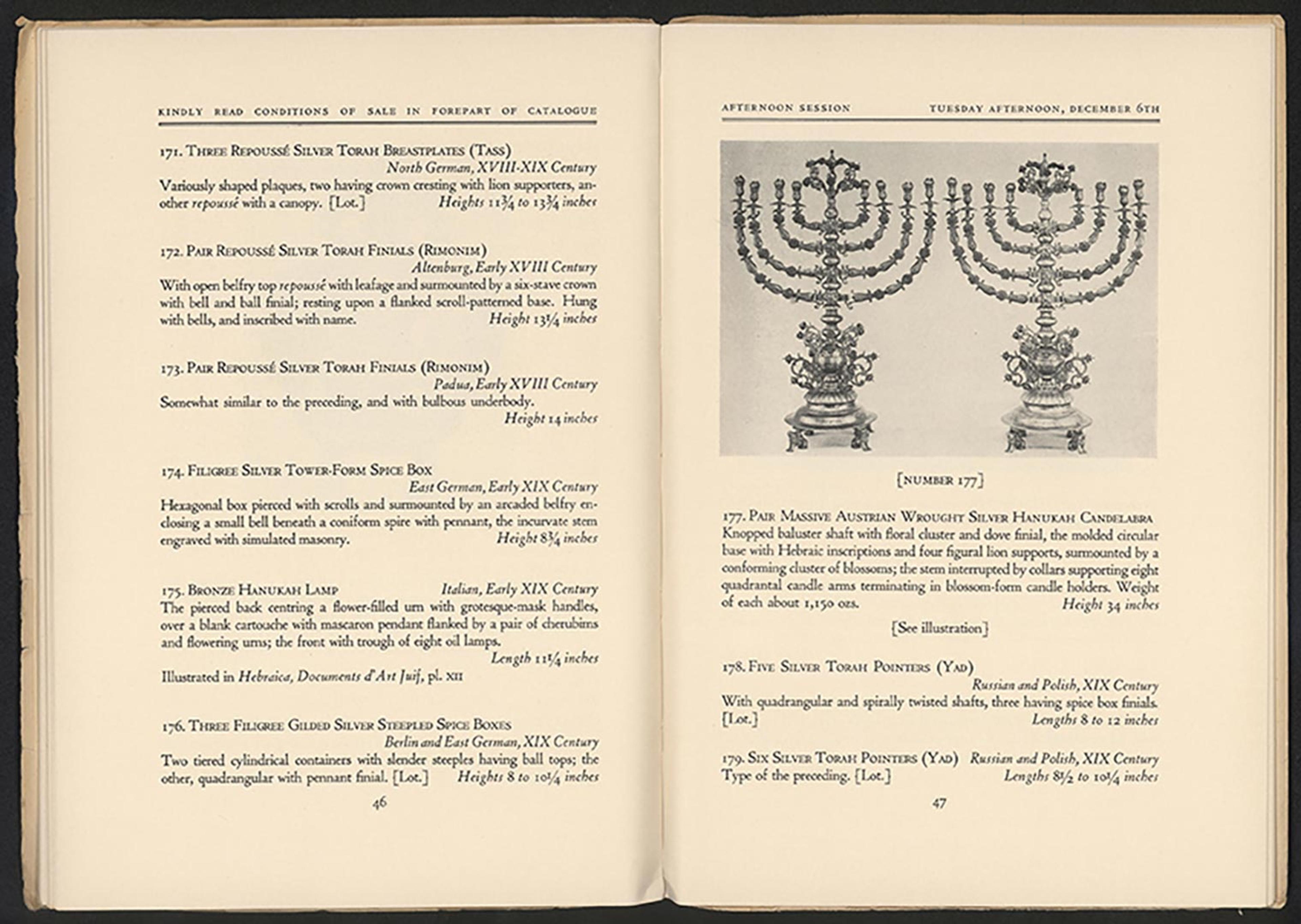

And what of the Moldovan lamp from Lemberg—the one without a shammash? All this time there has been no clear mention nor discernible image of it. Was it in the same synagogue, the second of two lamps described in the 1935 guidebook? The Moldovan hanukkiya only makes its first clear appearance—as one of two, neither apparently with a shammash—in the 1949 New York auction of the Mira Salomon collection. The Moldovan lamp is demonstrably the one at the right: one of the small flowers that held a candle is missing. It was later replaced by the current owner.

The Moldovan menorah pictured at right in the 1949 Salomon collection catalogue. Image courtesy Sothebys, New York

These silver lamps cannot be identified in the Salomon collection in Paris when it was catalogued in 1930, and the path that led from Lemberg to New York remains a mystery. To this day, its twin from the 1949 sale has not been identified (though it may be the same as the Jewish Museum example, its shammash obscured or missing when the photo was taken). Where were they hidden during the war? How did either of them survive?

Important chapters are still missing in the history of these works of art; entire volumes are forever lost from the story of the people who once tended them. In the face of such unconscionable human loss, is it right to speak of survival when what has been saved are inanimate objects? Can a precious object somehow call out on behalf of the lost ones who created them, polished them, lit them, prayed by them?

Hanukkah lamp (detail)

The Moldovan hanukkiya alone bears a Hebrew inscription on its base, taken from Psalm 36:9: “For with Thee is the fountain of life; in Thy light do we see light.” Have such works of art not carried the light of faith out of the darkness, like the oil that first lent its light to the miracle known as Hanukkah?

Special thanks to William Gross and Sergey Kravtsov in Israel, and to Joseph T. Moldovan, Sharon Mintz, and Abigail Rapaport in New York. Much of the literature about the synagogue and Judaica from Lemberg is in German and Polish. An accessible website on the history of Lemberg is available at Lviv’s Center for Urban History.

Updated on November 21, 2025 to reflect the menorah’s change in location from Gallery 556 to Gallery 554.