«The Cloisters museum and gardens came relatively late to the collection of late medieval glass vessels. The reasons are twofold: first, because very few of these objects have survived—they were everyday household objects, and fragile ones at that—and second, because collectors and scholars were slow to appreciate the elegant simplicity and skillful fabrication of these modest, utilitarian objects. The first glass vessel entered The Cloisters Collection in 1977 and, like all those to follow, was a product of the German-speaking world of central Europe, a vast region that supported an extensive glass-making industry. The three recent acquisitions discussed here significantly enhance the collection's holdings of these appealing tablewares.»

Left: Beaker (Krautstrunk), late 15th or early 16th century. Made in Germany, possibly the lower Rhineland. Free-blown green glass (Waldglas) with applied decoration; H. 3 1/2 in. (8.9 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Eugen Grabscheid, 1977 (1977.343)

The type of beaker shown above, known in German as a Krautstrunk or cabbage stalk, was widely produced. The applied dollops of glass drawn to a point are called "prunts." In addition to being visually distinctive, prunts also facilitated grip, which was particularly useful when the fortified contents were being imbibed—all the more so because, in the absence of cutlery, the hands could get very greasy over the course of a meal. (Forks were not yet in use; if you couldn't eat an item with a spoon, then hands were the rule.) The greenish color of the transparent glass is due to impurities in the raw materials, particularly iron oxide, and is typical of glass production throughout northern and central Europe. These glasses are known as Waldgläser, or forest glasses, because they were produced in forested regions where fuel was abundant. Furthermore, the trees that were burned—mostly beech—produced ash that was used for flux, which lowered the temperature at which silica would melt. Other typical examples of forest glasses are shown below.

Left: Beaker (Maigelein), late 15th century. Made in Germany, possibly the lower Rhineland. Mold-blown green glass (Waldglas); H. 2 3/16 in. (5.5 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, The Cloisters Collection, 1985 (1985.133.1). Right: Conical beaker, ca. 1450. Made in Germany, Trier (?), the middle Rhineland. Mold-blown green glass (Waldglas); H. 4 5/16 in. (11 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, The Cloisters Collection and Rogers Fund, 1991 (1991.99)

The shallow beaker at left was one of the more common forms of drinking vessels and was produced in both Germany and the Netherlands. The conical beaker at right, a form more familiar to us, was then rarer. Both these vessels are enhanced with cross-ribbed, spiraling surface patterns that were made by blowing a bubble of molten glass in a patterned dip mold, removing it, twisting it, reinserting it in the mold, and then twisting it in the opposite direction.

Beaker (Krautstrunk), ca. 1480–1510. Made in Germany or the Netherlands. Free-blown green glass (Waldglas) with applied decoration. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, The Cloisters Collection, 2011 (2011.21)

This shallow beaker with a single row of prunts is the rarest of the Krautstrunk type. It is often referred to as a Riemenschneider glass because it is occasionally represented in the sculptured altarpieces of the famed late medieval sculptor Tilman Riemenschneider (1460–1531, active in Würzburg).

Reliquary beaker (Krautstrunk), late 15th century. Made in Germany. Free-blown green glass (Waldglas) with applied decoration, wax, silk, linen, and ink on parchment; H. 4 1/16 in. (10.3 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, The Cloisters Collection, 2004 (2004.365)

Ordinary drinking vessels like this Krautstrunk were occasionally repurposed in the late Middle Ages to serve as inexpensive reliquaries, often embedded in an altar or wall of a church, only to be discovered centuries later. The relics here are wrapped in linen and silk and are identified on the accompanying parchment note. As the vessel has never been opened, the identity of the relics remains a mystery.

Detail of the reliquary beaker's wax seal

The wax seal, with the representation of a bishop kneeling before the seated Virgin and Child, bore an inscription as well as a coat of arms at the bottom, but both are so damaged that they no longer can aid in the identification of the original repository of the reliquary.

Beaker, late 13th or early 14th century. Made in Germany or Switzerland. Free-blown colorless glass with applied decoration; H. 3 9/16 in. (9.1 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, The Cloisters Collection, 2010 (2010.521)

This beaker is the earliest glass vessel in The Cloisters Collection and is distinguished by the colorless glass, which was achieved by the careful selection of raw ingredients and, most likely, the addition of manganese oxide as a decolorant to counter the color imparted by iron oxide. Colorless or near-colorless glass with a tinge of yellow was typical of production in southern Germany, Switzerland, and northern Italy. The glass is surprisingly thin, much more so than the forest glasses. A trailed glass thread separates the flared lip from the body, and a pincered ring foot supports the vessel. The prunts, in contrast to those of the Krautstrünke above, are smaller and more nubbin-like. A glass of this type appears to be represented in the famous Codex Manesse, an extensive compendium of late medieval ballads and epigrammatic poetry that was compiled between 1300 and 1340 in Zürich.

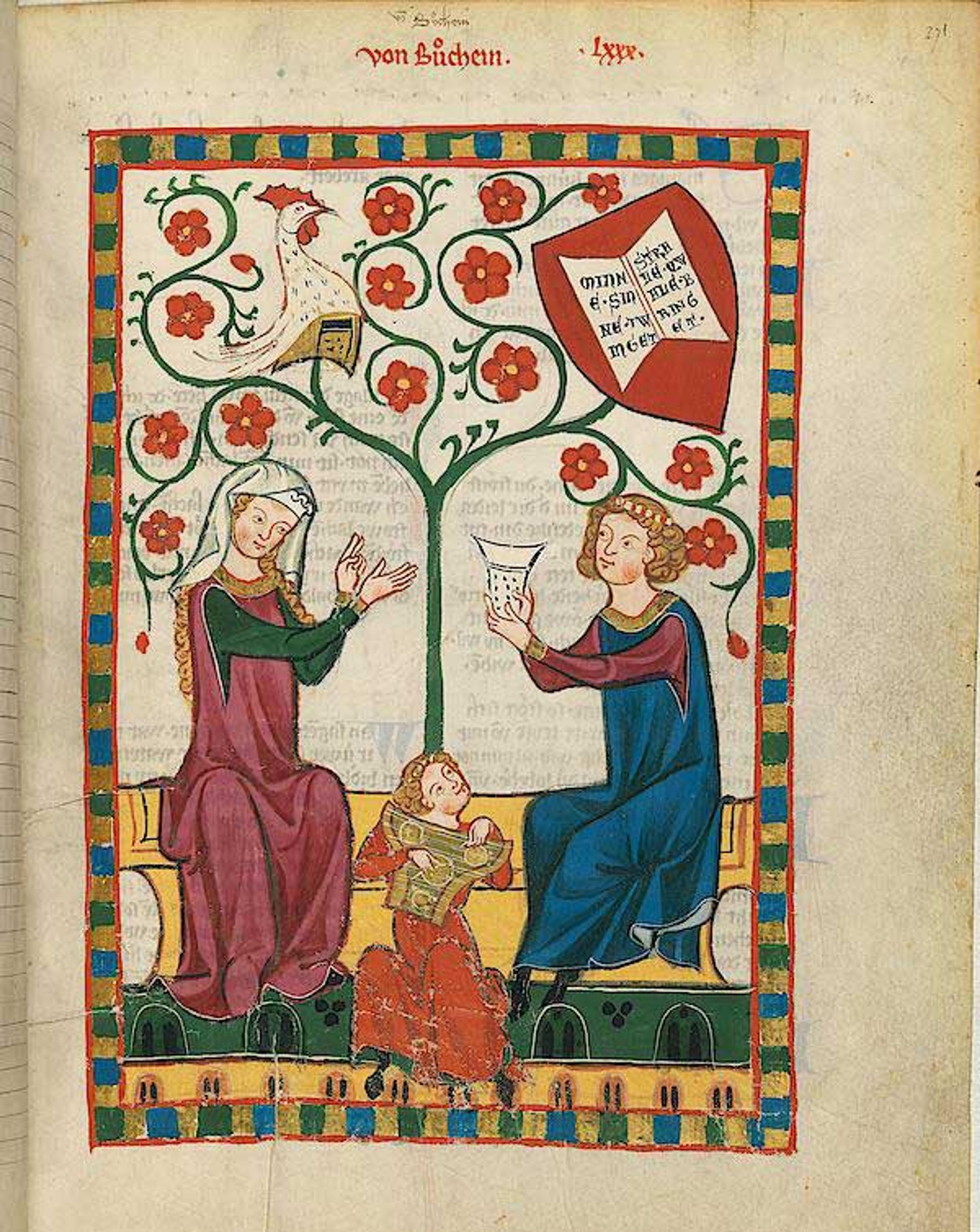

Universitätsbibliothek Heidelberg. Cod. Pal. Germ. 848, Große Heidelberger Liederhandschrift (Codex Manesse), ca. 1300–1340. Zürich. Image courtesy of the Universitätsbibliothek Heidelberg

The poet shown here, who hailed from Buchheim, near Freiburg, offers the beaker to a young lady, who appears eager to accept it. The courtly context suggests that the beaker was more valued than just an ordinary drinking vessel.

In 2013, The Cloisters was able to acquire three exceedingly rare and exceptional late fifteenth- or early sixteenth-century vessels.

Pilgrim Flask with the Corpus Christi, 1490–1510. Made in Germany, lower or middle Rhineland. Free-blown green glass (Waldglas) with applied decoration; H. 7 1/2 in. (19.1 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, The Cloisters Collection, 2013 (2013.647)

The intended purpose of this vessel is uncertain. Although inspired by pilgrims' flasks, the material alone makes it unsuitable for this purpose. Furthermore, the body of the vessel is compressed in the center, significantly reducing its capacity. It is unlikely, then, that this was intended as a mere flask. The hollow body of Christ is connected to the interior of the flask, so it is possible to fill either the interior or the body of Christ or both with wine or other liquids. One wonders if it could have been used in some ritual fashion on Corpus Christi Day. This type of vessel is otherwise known only through fragments.

Footed cup with handle (Scheuer), ca. 1500–25. Made in Germany, lower or middle Rhineland. Free-blown green glass (Waldglas) with applied decoration; H. 4 3/4 in. (12 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, The Cloisters Collection, 2013 (2013.648)

The cup-like form of this glass with a single handle was inspired by contemporary metalwork; in both glass and metalwork, a simple ring foot usually supports the cup. The elaboration of the form with a stem and a pincered knob is unique to this vessel.

Beaker with open-work foot, ca. 1500–25. Made in Germany, lower or middle Rhineland. Free-blown green glass (Waldglas) with applied decoration; H. 3 3/4 in (9.6 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, The Cloisters Collection, 2013 (2013.649)

This vessel is essentially a shallow beaker with one row of prunts—like the Krautstrunk above—that has been elaborated with a short stem and a foot of open-work trail glass. Only two other examples of this type are known.

With the addition of these three glass vessels, our table is distinctly upgraded.