Photography and the American Civil War, by Jeff Rosenheim, features 297 color images and is available in The Met Store.

«Photography was invented just twenty years before the American Civil War. In many ways the war—its documentation, its soldiers, its battlefields—was the arena of the camera's debut in America. "The medium of photography was very young at the time the war began but it quickly emerged into the medium it is today," says Jeff Rosenheim, curator of the current exhibition Photography and the American Civil War(on view through September 2), and author of its accompanying catalogue. "I think that we are where we are in photographic history, in cultural history, because of what happened during the Civil War . . . it's the crucible of American history. The war changed the idea of what individual freedom meant; we abolished slavery, we unified our country, we did all those things, but with some really interesting new tools, one of which was photography."»

Timothy H. O'Sullivan, Pennsylvania Light Artillery, Battery B, Petersburg, Virginia, 1864. Albumen silver print. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Harris Brisbane Dick Fund, 1933 (33.65.241)

As the catalogue discusses, photography served many purposes during the war. It was used to promote abolition; as propaganda for both the northern and southern causes; as an important tool in the creation of Lincoln's public persona and career; as well as for reconnaissance and tactical observation. The Civil War also marks the beginning of photojournalism as we understand it today. Photographers in the field who worked for name-brand studios like those of Mathew B. Brady and Alexander Gardner can be understood as the first embedded journalists. In his illuminating text, Rosenheim posits that Brady and the many others who made the photography of war their business came to understand the social responsibility that was part of their art, the responsibility the camera gave them.

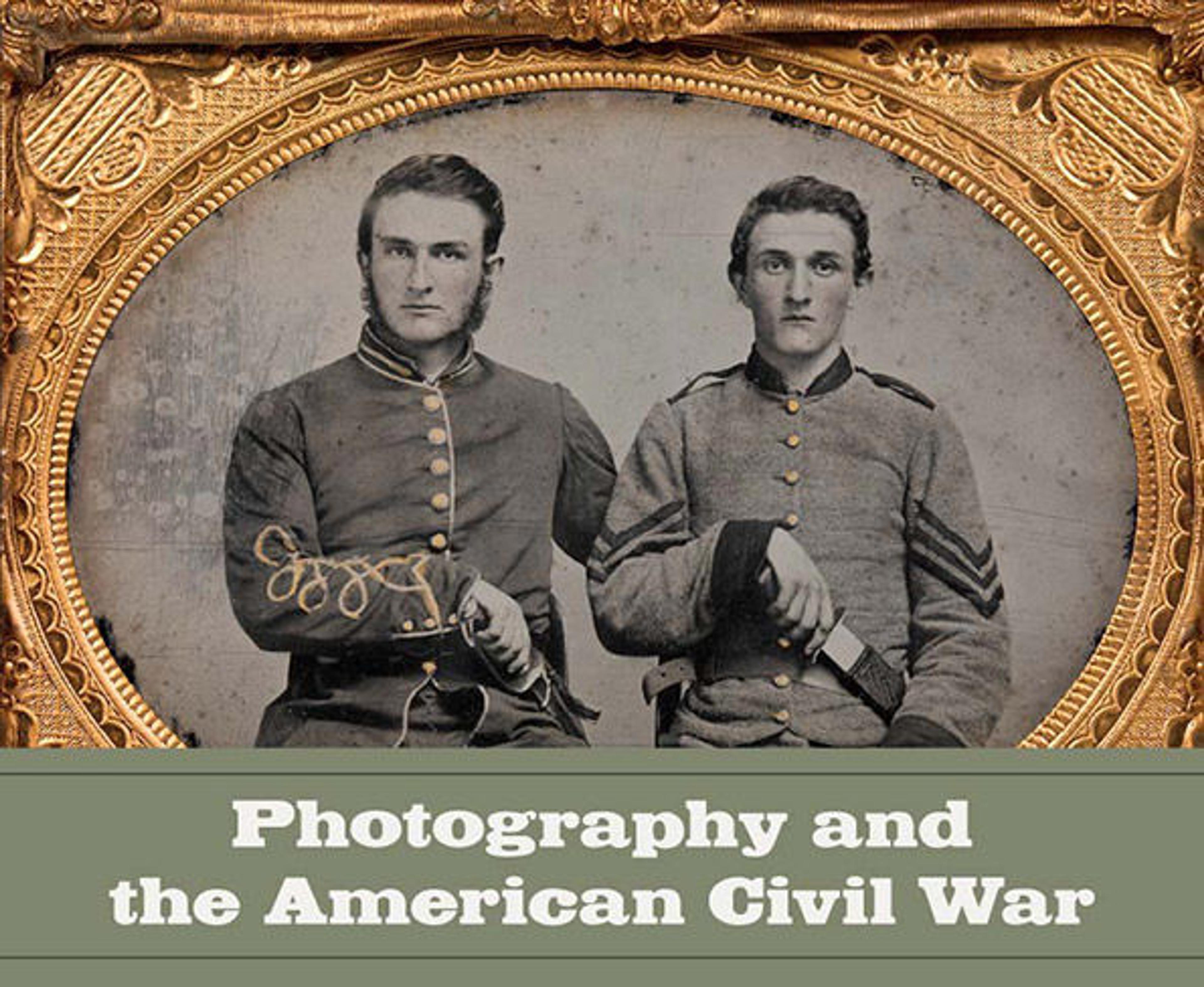

Clockwise: Unknown artist. The Pattillo Brothers, Company K, "Henry Volunteers," Twenty-second Regiment, Georgia Volunteer Infantry, 1861–63. Quarter-plate ruby glass ambrotype with applied color. David Wynn Vaughn Collection; Unknown artist, Confederate Corporal (?) with British Rifle Musket and Bowie Knife, Likely from Georgia, 1861–62 (?), Sixth-plate ambrotype with applied color. David Wynn Vaughn Collection; Unknown artist, Private James House, Sixteenth Georgia Cavalry Battalion, Army of Tennessee, 1861–62 (?). Sixth-plate ruby glass ambrotype. David Wynn Vaughn Collection

"The Civil War created an incredible demand for photography. It was used by the Union and Confederate armies and of course by regular Americans who wanted photographs of their family members heading into danger, and of the battle scenes themselves," Rosenheim explains. "It's hard to imagine the pathos of people buying photographs of battlefields and slaughter and meticulously inserting the prints into photography portrait albums. But this was happening on a mass scale. I think there may have been a superstitious element to it. Families may have felt that if they could put pictures of their brothers, sons, husbands into an album—to contain their likenesses in some way—that they could stop their death." As the catalogue discusses, most stationers and portrait galleries—and there were many—were in business to accommodate soldiers' needs. People were dying so quickly, families wanted something to hold on to. This tremendous demand galvanized a rapid advancement in camera technology in the Civil War years, allowing for easier and cheaper photography. "This was a time of great democratic change," says Rosenheim. By 1863, thousands of people could afford to buy and commission photographs. "To see a photograph of yourself gave people a sense of their individuality."

Unknown artist, "Picture Gallery Photographs," 1860s. Albumen silver print (carte de visite). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, Alfred Stieglitz Society Gifts, 2013 (2013.57)

In his planning for the exhibition, Rosenheim scoured records from photography historians and from Civil War specialists, the military, newspapers, the Library of Congress, and websites developed by individuals simply uploading family portraits. "All of this incredible information is coming together on the Web—enlistment records, photographs with rare period inscriptions on the verso, scans of newspaper engravings—and now in many cases we are able to put together who made the photographs, where and when they were made, and who or what regiment is depicted. Every day something new is added to the digital universe, be it a new name in a government database, or the discovery of a single photograph from someone's attic."

Attributed to Andrew Joseph Russell, Laborers at Quartermaster's Wharf, Alexandria, Virginia, 1863–65. Albumen silver print. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Harris Brisbane Dick Fund, 1933 (33.65.40)

Related Link

The Met Store