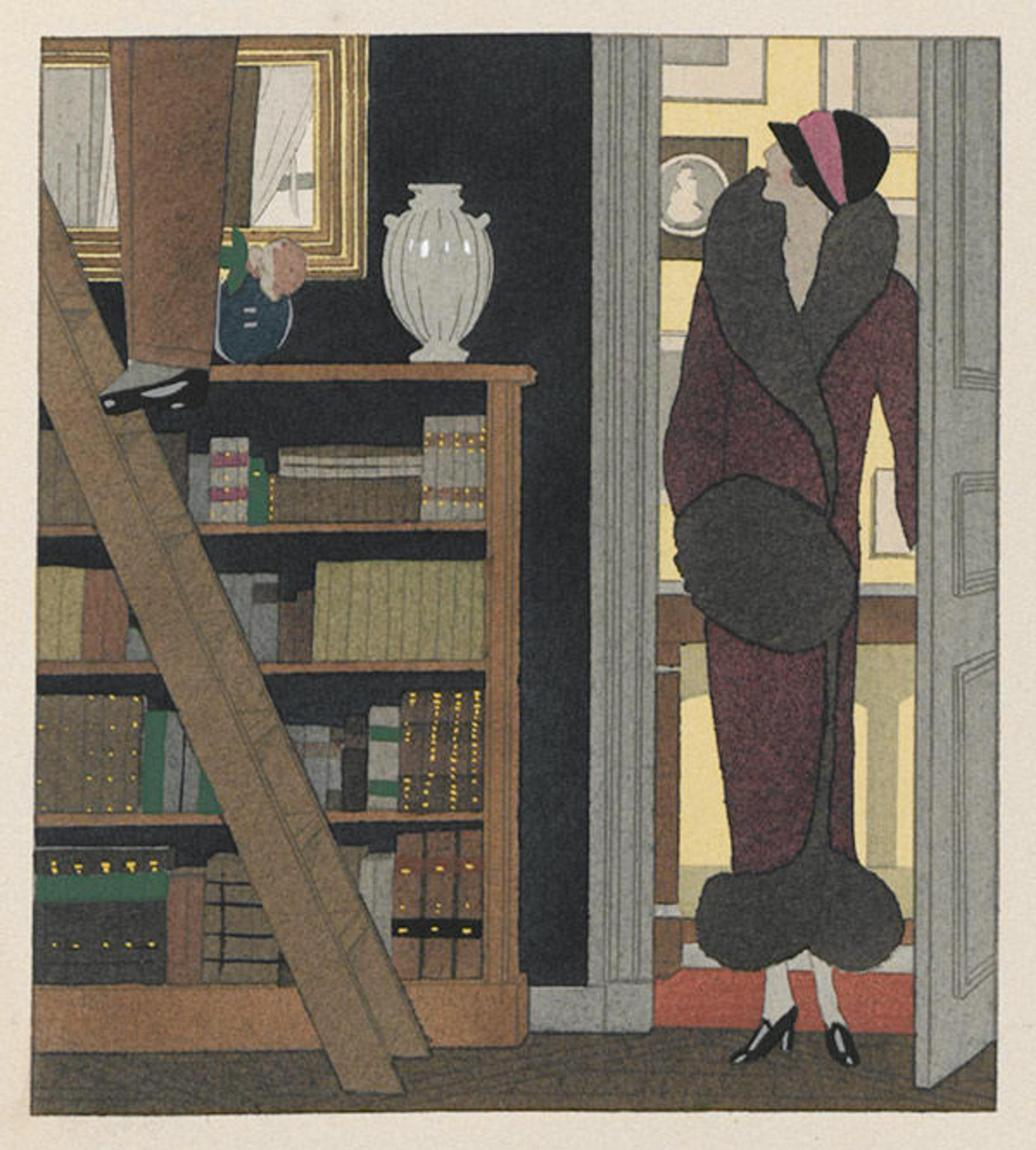

Illustration by André E. Marty for Constance dans les Cieux by Comte de Bondy (Servant, 1925)

«In the first installment in this series on Les Artistes du Livre, we looked at folios that included illustrations of canonical works of fiction and standard texts. The folios described in this second installment include illustrations that demonstrate the surprising variety of mood and tone—from the morose to the sanguine—that can be found in this series.»

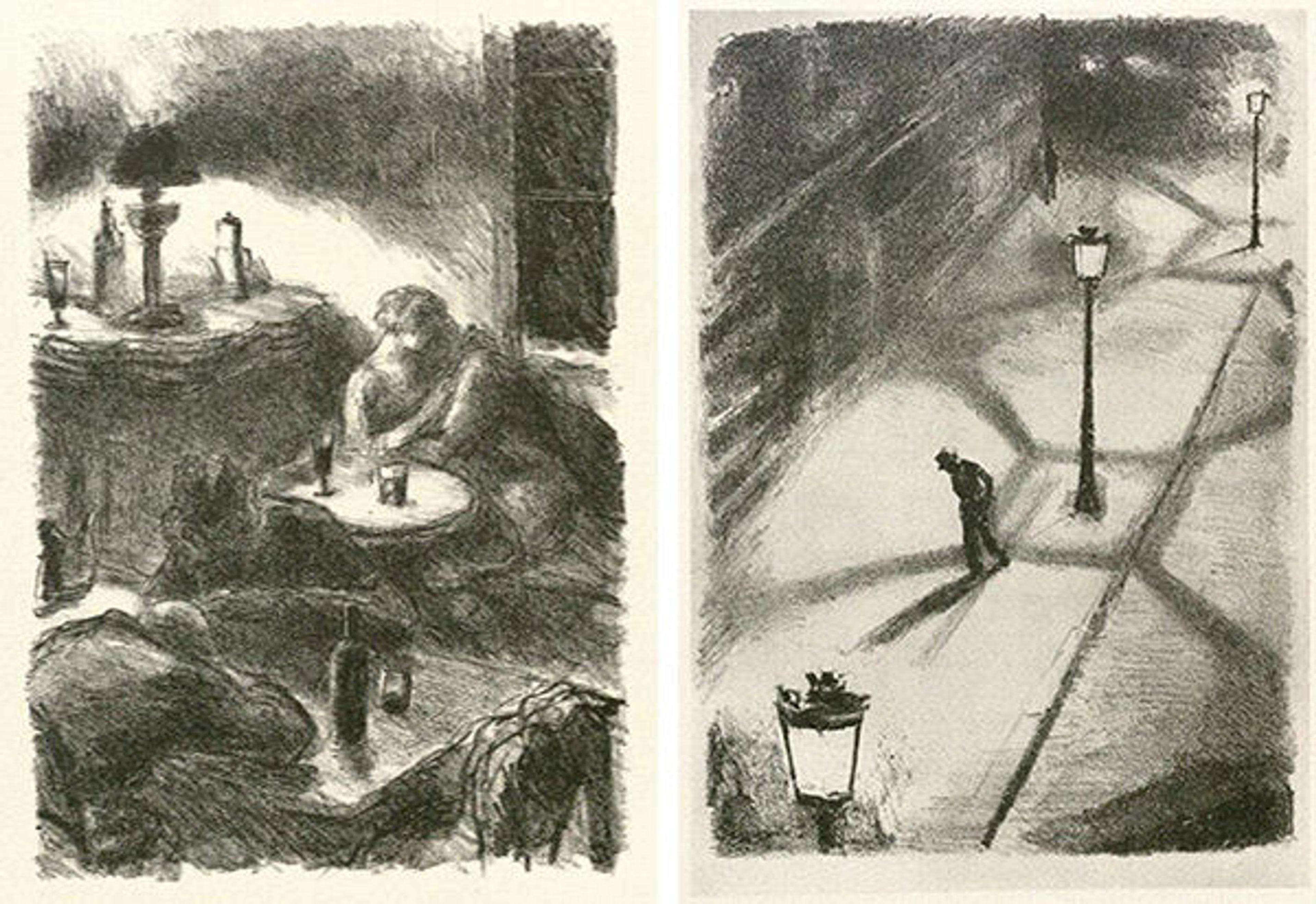

Left: Illustration by Charles Désiré Berthold-Mahn for Le Feu by Henri Barbusse (Les Oeuvres Représentatives, 1930). Right: Illustration by Charles Désiré Berthold-Mahn for Confession de Minuit by Georges Duhamel (Jonquières, 1926)

Several of the illustrations in Les Artistes du Livre accompany texts that explore sobering topics such as war, social inequality, and urban alienation. For instance, the folio on Charles Désiré Berthold-Mahn includes his illustrations for Henri Barbusse's Le Feu, a novel based on Barbusse's own experiences during World War I (above-left image).1 Berthold-Mahn also illustrated Georges Duhamel's Confession de Minuit, the first volume of the novel cycle Vie et Aventures de Salavin, which recounts the story of a man in extreme moral distress (above-right image).2

Left: Illustration by Almery Lobel-Riche for Le Spleen de Paris by Charles Baudelaire (G. Briffaut, 1922). Right: Illustration by André E. Marty for Gazette du Bon Ton (Librairie Centrale des Beaux-Arts, 1912–1925)

Bleak imagery also abounds in the folio on Almery Lobel-Riche, which features his arresting illustrations for Le Spleen de Paris, Baudelaire's collection of poems set against the backdrop of modern Paris (above-left). Lobel-Riche's images provide a stark contrast to the lighter illustrations in the folio dedicated to André E. Marty. This latter artist's easy and graceful approach, as well as attention to fashion, can be seen in his illustrations for Gazette du Bon Ton (above-right) and the novel Constance dans les Cieux by Comte de Bondy (see this post's first image).

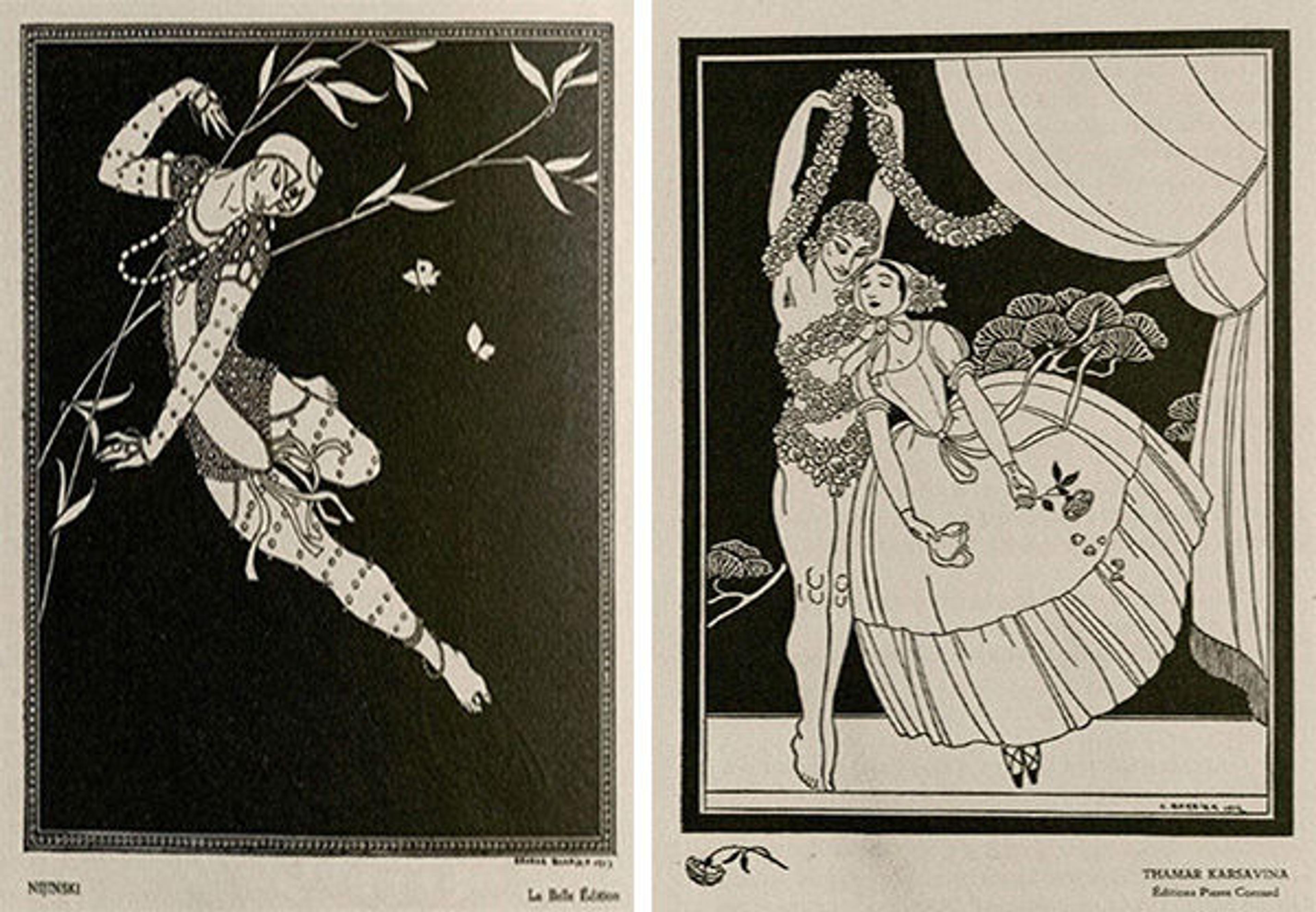

Left: Illustration by George Barbier for Danses de Nijinski by Glose de Francis de Miomandre (La Belle Édition, 1913). Right: Illustration by George Barbier for Album Dédié à Tamara Karsavina by Jean-Louis Vaudoyer (Pierre Corrard, 1914)

In addition to the works by Marty, illustrations of a more lighthearted nature can be found in the George Barbier folio. Complementing his output as an illustrator, Barbier designed costumes and sets for the theater and film industry.3 He was also a fashion designer, and many of his illustrations are featured in the fashion periodical Modes et Manières d'Aujourd'hui. The images of the ballet dancers Nijinsky and Karsavina, seen above, are from Barbier's first two illustrated books, published in 1913 and 1914.4

Illustrations by Paul Jouve for La Chasse de Kaa by Rudyard Kipling (Javal et Bourdeaux, 1930), part of The Jungle Book collection of stories

The playful illustrations for The Jungle Book found in the Paul Jouve folio, such as the ones featured above, are particularly endearing, perhaps because they tap into one's childhood memories of having enjoyed Kipling's story in various media, as either a text, picture book, or film.

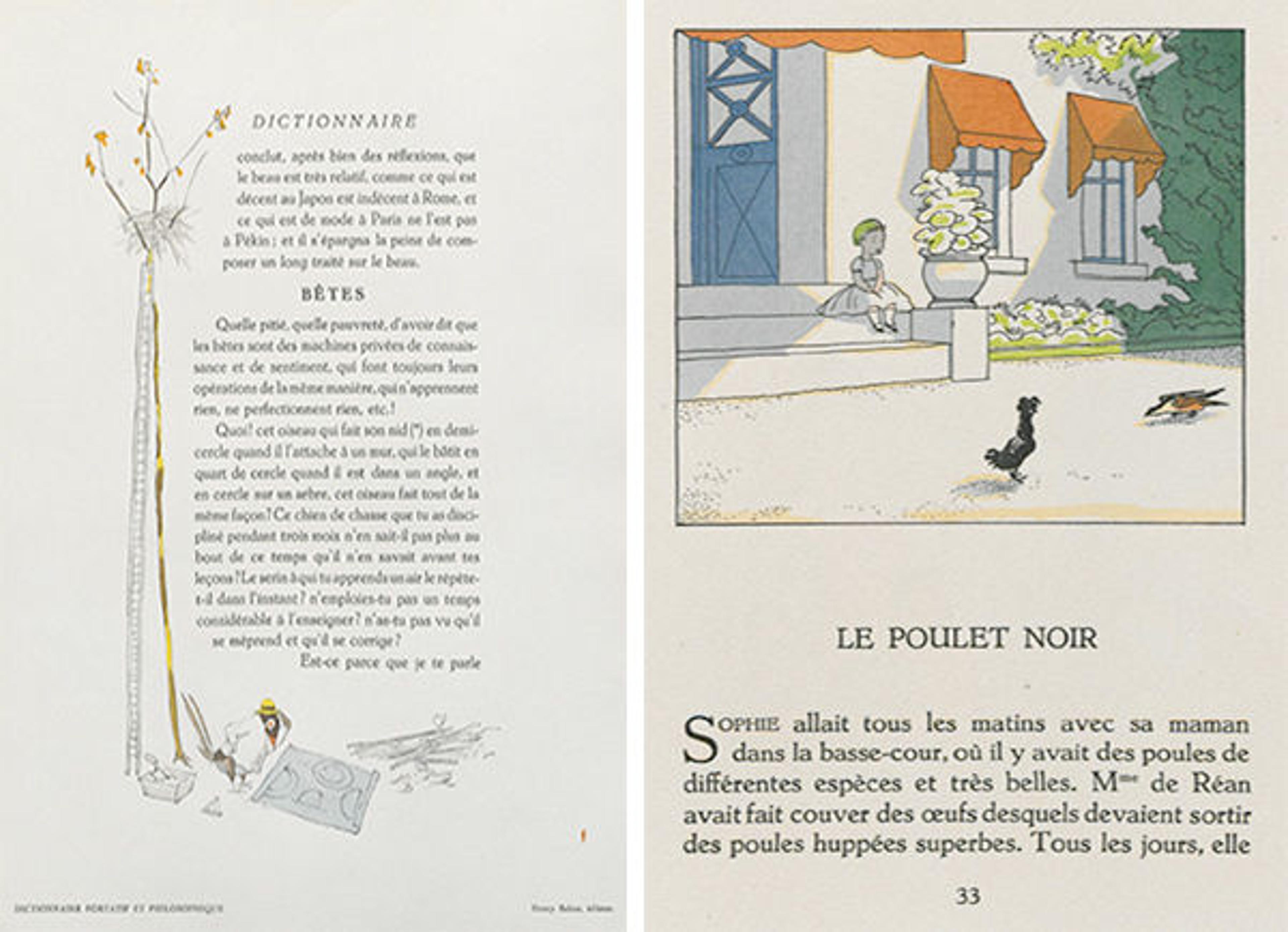

Left: Illustration by Jacques Touchet for Le Dictionnaire Portatif et Philosophique by Voltaire (Henry Babou, 1928). Right: Illustration by Jacques Touchet for Les Malheurs de Sophie by Comtesse de Ségur (Piazza, 1930)

Lastly, no post about Les Artistes du Livre would be complete without calling attention to the whimsical illustrations in the Jacques Touchet folio, many of which are based on fables, fairy tales, and children's books. In addition to illustrating the beloved and ubiquitous Les Malheurs de Sophie (above-right image), Touchet also provided illustrations for Voltaire's Le Dictionnaire Portatif et Philosophique (above-left image).

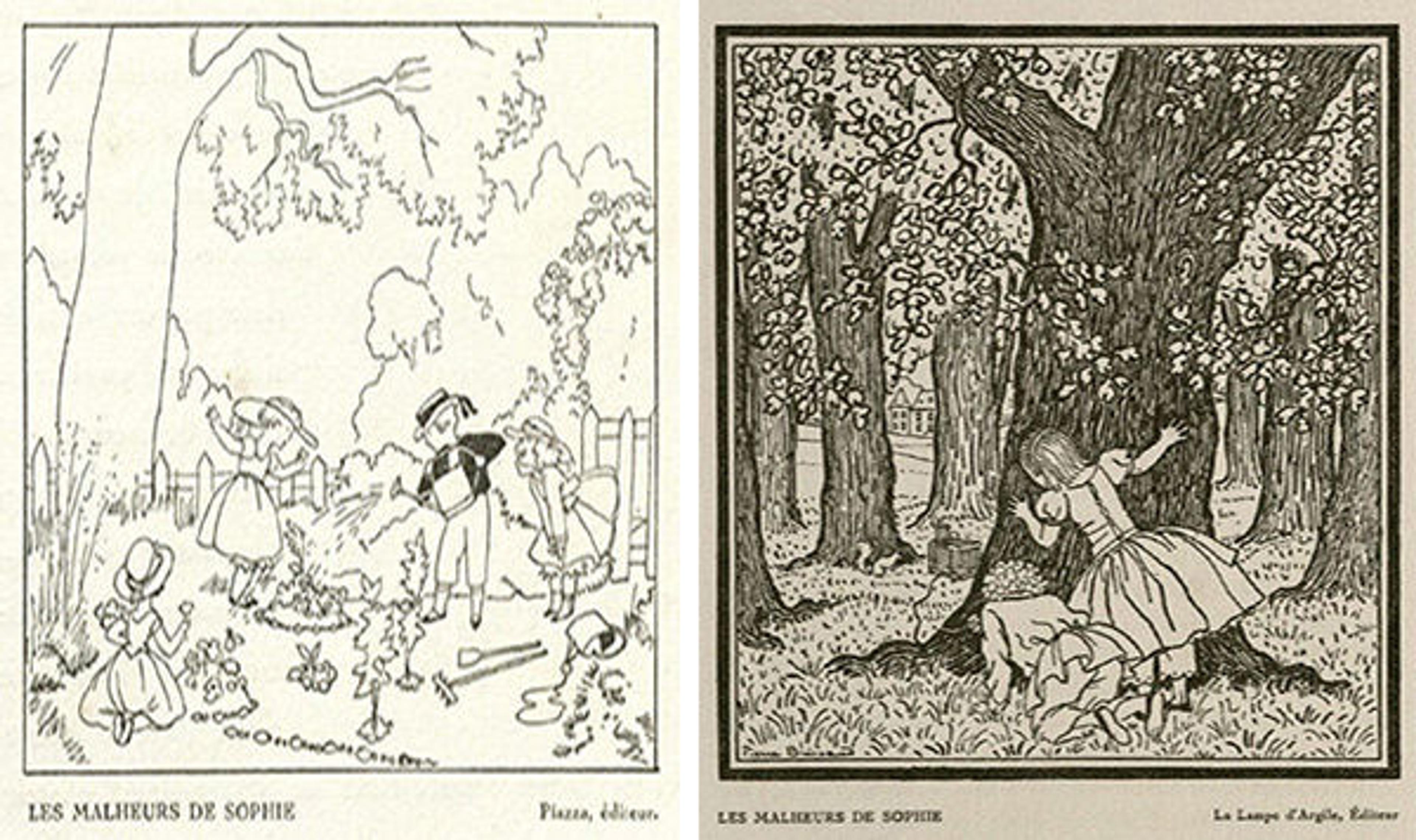

Left: Illustration by Jacques Touchet for Les Malheurs de Sophie by Comtesse de Ségur (Piazza, 1930). Right: Illustration by Pierre Brissaud for Les Malheurs de Sophie by Comtesse de Ségur (La Lampe d'Argile, 1923)

It is interesting to compare the rendition of Les Malheurs de Sophie by Touchet with that of Brissaud, as seen in the images above. In his essay on Brissaud, Jean Dulac writes:

"In our memory, the books of Madame de Ségur are so inseparable from the form in which we loved them in our childhood, from this red and gold cover, from these illustrations of Castelli or of Bertall, that we could not say if they are good or bad: since it is not drawings, works of art, that our ten-year-old eyes saw in them, it was the characters themselves with which Madame de Ségur made us live, it was Sophie, Madame de Réau or Madame Fichini."5

Illustration by George Barbier for Le Cantique des Cantiques (La Belle Édition, 1914)

Illustration by Charles Désiré Berthold-Mahn for Berthold-Mahn, Les Artistes du Livre (H. Babou, 1929)

As the above quote suggests, there is indeed a seemingly inextricable tie that is created between the stories we read as children and the illustrations that accompany them. While Les Artistes du Livre encompasses illustrations from a range of texts, including many with somber subject matter, leafing through this collection cannot help but to instill in us an ineffable nostalgia for our childhood and for that time when we first connected pictures and words.

[1] Raymond Geiger, Berthold-Mahn, Les Artistes du Livre (Paris: H. Babou, 1929), 28. From Britannica Online, s.v. "Henri Barbusse," accessed December 15, 2014, http://0-academic.eb.com.library.metmuseum.org/EBchecked/topic/53006/Henri-Barbusse.

[2] Raymond Geiger. Berthold-Mahn, Les Artistes du Livre (Paris: H. Babou, 1929), 24–5. From Britannica Online, s.v. "Georges Duhamel," accessed December 15, 2014, http://0-academic.eb.com.library.metmuseum.org/EBchecked/topic/173203/Georges-Duhamel.

[3] Benezit Dictionary of Artists, s.v. "Barbier, Georges," accessed December 15, 2014, http://0-www.oxfordartonline.com.library.metmuseum.org/.

[4] Jean-Louis Vaudoyer, George Barbier, Les Artistes du Livre (Paris: H. Babou, 1929), 28.

[5] Jean Dulac, Pierre Brissaud, Les Artistes du Livre (Paris: H. Babou, 1929), 28.

Related Link

In Circulation: Pictures and Words: Book Illustration in Interwar France