The current exhibition Reconfiguring an African Icon: Odes to the Mask by Modern and Contemporary Artists from Three Continents reflects the dynamic intersection of two areas of the Museum's permanent collections—it is presented in the spacious passageway between the galleries of modern art and those dedicated to the arts of Africa, Oceania, and the Americas.

View of the installation. © The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Recent sculptural works by Romuald Hazoumé and Calixte Dakpogan, who live and work in the Republic of Benin, and by American artists Lynda Benglis and Willie Cole attest to a shared engagement with the African mask as a source of inspiration across the global contemporary art scene.

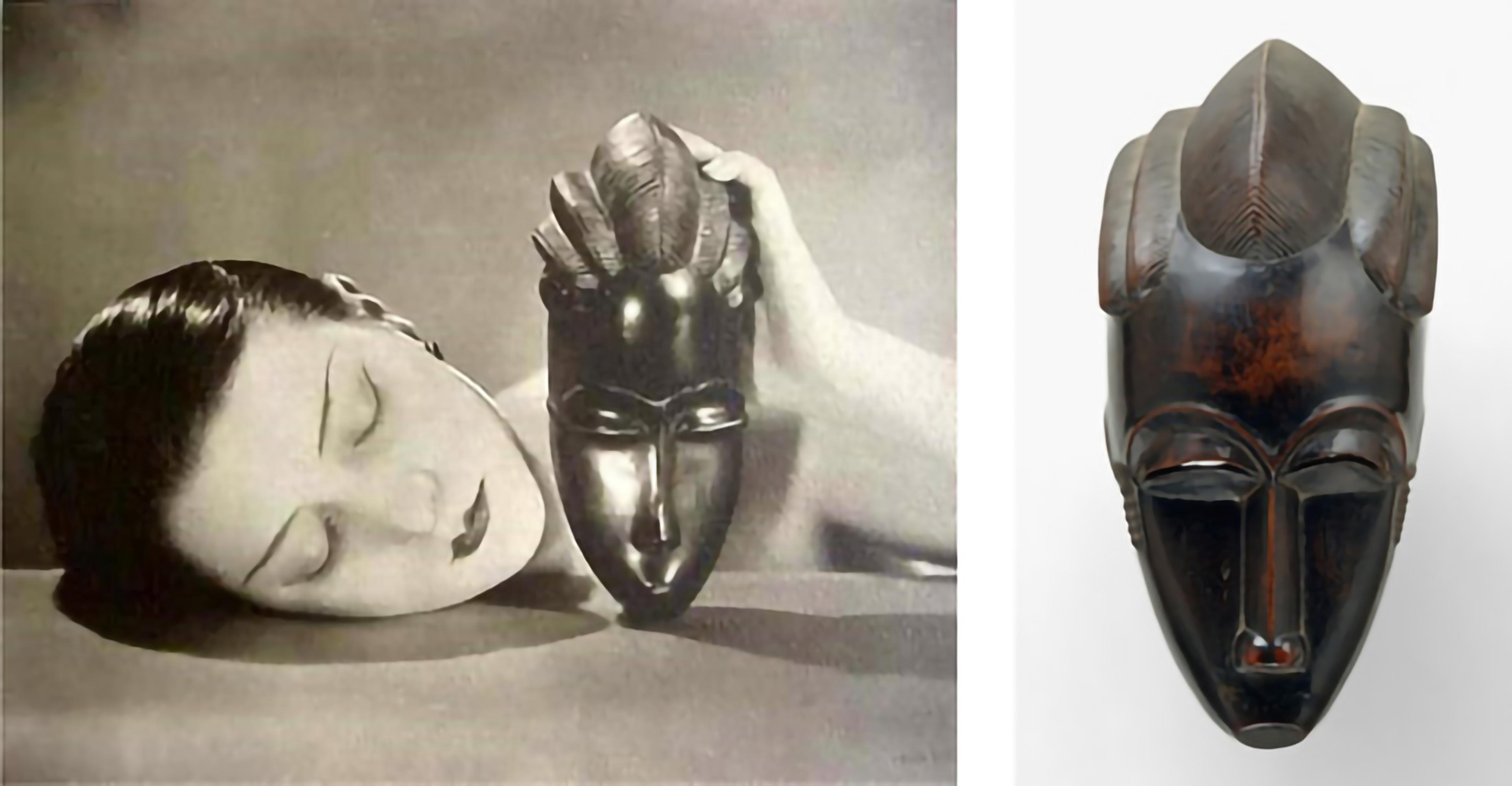

Left: Man Ray (American, 1890–1976). Noire et Blanche, 1926. Private Collection, New York. © 2011 Man Ray Trust / Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY / ADAGP, Paris; Right: Portrait Mask (Gba gba). Côte d'Ivoire; Baule peoples, before 1913. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Bequest of Adrienne Minassian, 1997 (1997.277)

Eighteen works by these four contemporary artists are introduced in the installation by Man Ray's iconic photographic composition Noire et Blanche (1926) and a Baule mblo portrait mask from Côte d’Ivoire that circulated within Modernist circles in Paris as early as 1913. The pairing of these two works reminds us of the first decades of the twentieth century, when artists from the European avant-garde were introduced to African sculpture. Building upon that history, and informed by their own perspectives, the artists in Reconfiguring an African icon reflect on a century of viewing the mask as a disembodied wood artifact—that is, as an art object in a museum removed from its original performative context. They do so by reinterpreting the African mask through sculptures made in a variety of unconventional materials.

Romuald Hazoumé (Beninese, b. 1962). Left: Coconut, 1997. Plastic can, synthetic hair, metal, nylon; 14 1/2 x 8 5/8 x 5 7/8 in. (37 x 22 x 15 cm). Right: Ear Splitting, 1999. Plastic can, brush, speakers; 16 1/2 x 8 5/8 x 6 1/4 in. (42 x 22 x 16 cm). Both: Courtesy CAAC - The Pigozzi Collection, Geneva. © Romuald Hazoumé

Romuald Hazoumé's signature works, his "jerrican masks," are made from yellow, red, silver, and black plastic and metal containers. In the Republic of Benin, these containers are used primarily for the illegal transportation of oil from neighboring Nigeria.

The stall of a gasoline street vendor, Route des Pêches, Cotonou, Republic of Benin, 2011. © Yaëlle Biro

I saw this phenomenon first hand while traveling in the Republic of Benin, where the unofficial oil market is omnipresent along the country’s roads. Confronted with the many gasoline street vendors and the motorcycles transporting hundreds of liters of the precious liquid in these plastic containers, one easily understands Hazoumé’s fascination with this medium: the jerricans are like thousands of expressive faces looking back at the passerby.

View of Romuald Hazoumé's studio, Porto Novo, Republic of Benin, 2011. © Yaëlle Biro

In his reinterpretations of the mask, Hazoumé utilizes each container as a ready-made canvas: orienting their upper surface toward the viewer, the handle becomes a nose, the beaker a mouth. Eyes, hairdos, and ears are made from applied found objects as diverse as headphones, brushes, wigs, electric cables, and more—the remnants of Western consumerist society. Hazoumé’s interest in masks goes back to his childhood, when he created masks for Kaléta, an initiation for boys among the Yoruba peoples of eastern Benin. Living in Germany, he realized the appeal masks had on his European friends.

Singers and dancer wearing an articulated bird mask during the Gèlèdé ceremony organized by the Setto family, in the Zogba quarter of Covè, Republic of Benin, May 8, 2011. © Yaëlle Biro

Today Hazoumé himself is a collector of masks; he owns a number of wooden headdresses, the sculpted component of the Yoruba masquerade known as Gèlèdé that he acquired from families of carvers who still practice the art.

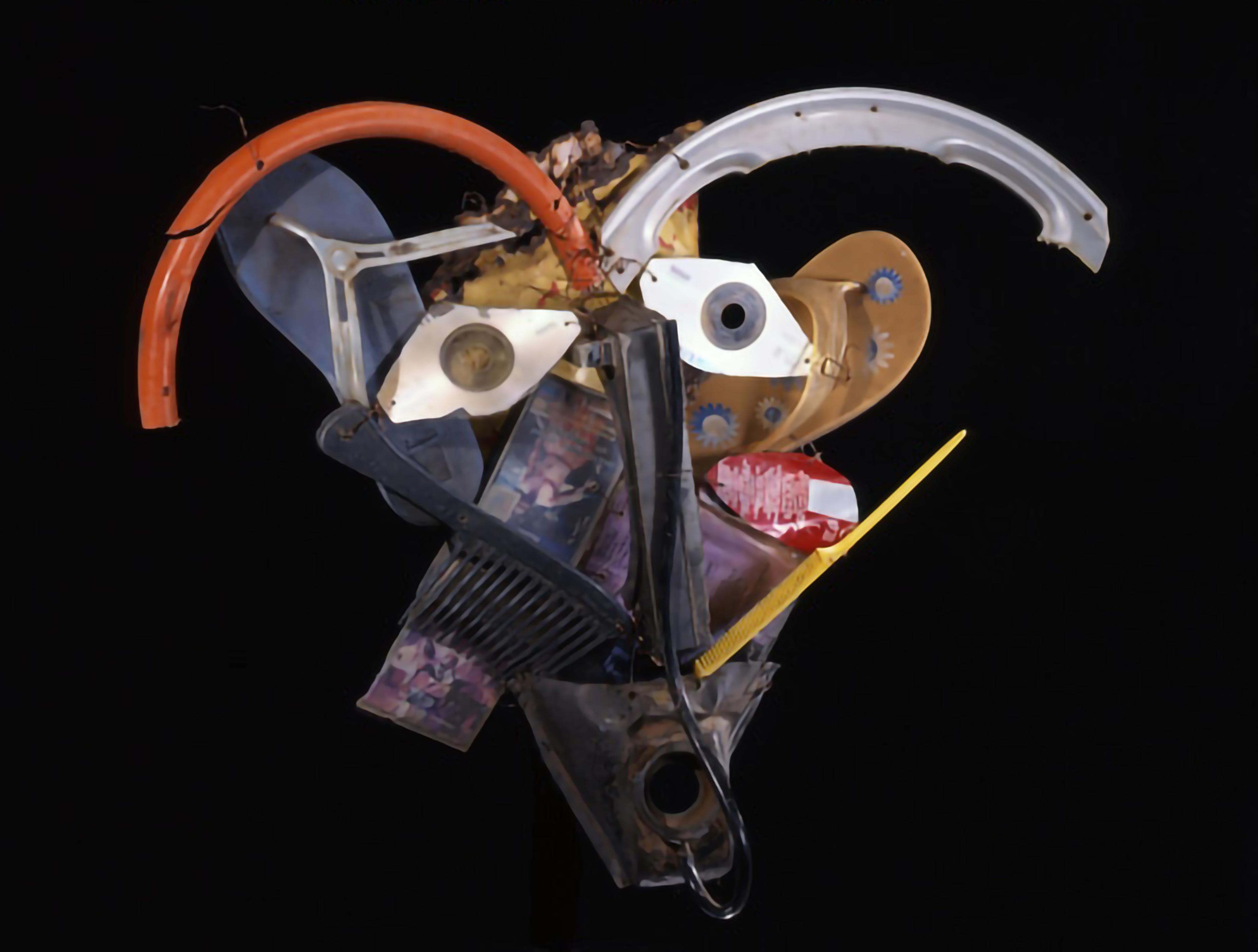

Calixte Dakpogan (Beninese, b. 1958). Heviosso, 2007. Metal, plastic (shoes and combs), CD, tape; H. x W. x D.: 29 1/8 x 21 5/8 x 11 1/4 in. (74 x 55 x 28.5 cm). Courtesy CAAC - The Pigozzi Collection, Geneva. © Calixte Dakpogan

The descendant of the royal blacksmiths of Porto-Novo, Calixte Dakpogan began creating secular works—together with his brother Théodore and cousin Simonet Biokou—in the early 1990s. Dakpogan’s use of discarded consumption goods in his ingenious sculptural compositions reflect upon coastal Benin's long history of exchanges that have defined its religious and political history. The country is the spiritual center of vodun, a faith that was disseminated to communities throughout the Americas as a result of the Atlantic slave trade.

Shrine dedicated to Gu, compound of vodounon Sedjro Hounnoukpo Houffossi in Grand Popo, Republic of Benin, 2011. © Yaëlle Biro

Several of Dakpogan’s works relate to the complex pantheon of vodun deities in Benin. Gu, the deity of iron and war, is patron of the blacksmiths and craftsmen. Dakpogan’s extensive inclusion of metal in his work refers to that relationship. The primordial role of Gu is manifest throughout Benin, from small private shrines in the form of accumulated pieces of iron kept by vodunpractitioners to larger sculptural representations of the deity located in important spiritual sites.

Calixte Dakpogan in his studio, Porto-Novo, Republic of Benin, 2011. © Yaëlle Biro

More recently, Dakpogan has incorporated a broader range of objects and materials into his creative process. Items such as combs, sandals, forks, beads, light bulbs, hair, and plastic shells, among others, now shape the features of his whimsical creations. Consciously invoking the mask's importance as it relates to regional expression and to its centrality to the art historical canon, Dakpogan reflects with humor on this status through a highly inventive synthesis of unexpected yet familiar elements.

View of the installation. © The Metropolitan Museum of Art

A longtime African art amateur, Willie Cole also mines his own environment for materials to create sculptures that reference African masks. What appeals to him is the idea of taking an American artifact and "making it African," thereby reflecting on his own African-American identity. In an interview recorded last March, Cole explained that, when creating Shine, an assemblage of black high-heeled shoes tightly compressed together to form a powerful visage, he did not have a specific type of African mask in mind. The link between this work and African masks comes from what he sees as the relationship between the performative nature of his own creative process and that of African masquerades. Sifting through thrift shops of his native New Jersey, he selected the bright pink bicycle frame and linoleum kitchen set at the core of the other works in the installation, Next Kent Tji Wara and Kitchen Tji Wara. These are direct quotations of ci wara headdresses (or tji wara) worn by dancers during masquerades that mark agricultural cycles among the Bamana peoples of Mali (see example). A graphic designer by training, Cole was attracted to the crisp curving lines of these headdresses, defined by alternating negative and positive space.

Lynda Benglis (American, b. 1941). From left to right: Anacoco, 2010; Tullulah, 2010; Ville Platt, 2010. Made at the Museum of Glass, Tacoma, WA. Works courtesy of the artist and Cheim & Read, New York. PHOTOS COURTESY CHEIM & READ, NEW YORK. Art © Lynda Benglis/Licensed by VAGA, New York, NY

Lynda Benglis’s recent green, yellow, and black works in glass echo the shapes of the Fang ngil masks from Gabon in a more immaterial form. Her purchase of a tourist market ngil mask from a street vendor in front of the Whitney Museum of American Art triggered this series, exhibited here for the first time. She was struck by the vendor’s informed sale pitch, highlighting the importance of such works from Africa on the European avant-garde. This resonated with her interest in African arts, which goes back to the 1970s. In this new series of sculptures, she reflects on concepts of beauty and authenticity by reproducing the form of a work that was itself intended for the market.

The classic African mask is a carved wooden artifact. In its original context, however, it is a complex and dynamic art form that may be fully appreciated in relation to dance, costume, and music. Media added to their surfaces additionally imbued them with mystical powers. Such dynamism finds parallel expression in the work of these four artists who are operating outside the mask’s traditions. Using humor and irony as their primary medium, the artists respond in a playful way to the sheer physicality of the mask. Simultaneously alluding to its spiritual quality, each of their works pays tribute to the powerful legacy of the African mask and its infinite potential for reinvention.

Yaëlle Biro is assistant curator for the arts of Africa in the Department of the Arts of Africa, Oceania and the Americas.

Related Links

Exhibition: Reconfiguring an African Icon: Odes to the Mask by Modern and Contemporary Artists from Three Continents

Met Podcast Episode (March 21, 2011)

Yaëlle Biro discusses with artist Willie Cole the African mask as a source of inspiration for his works featured in the exhibition.