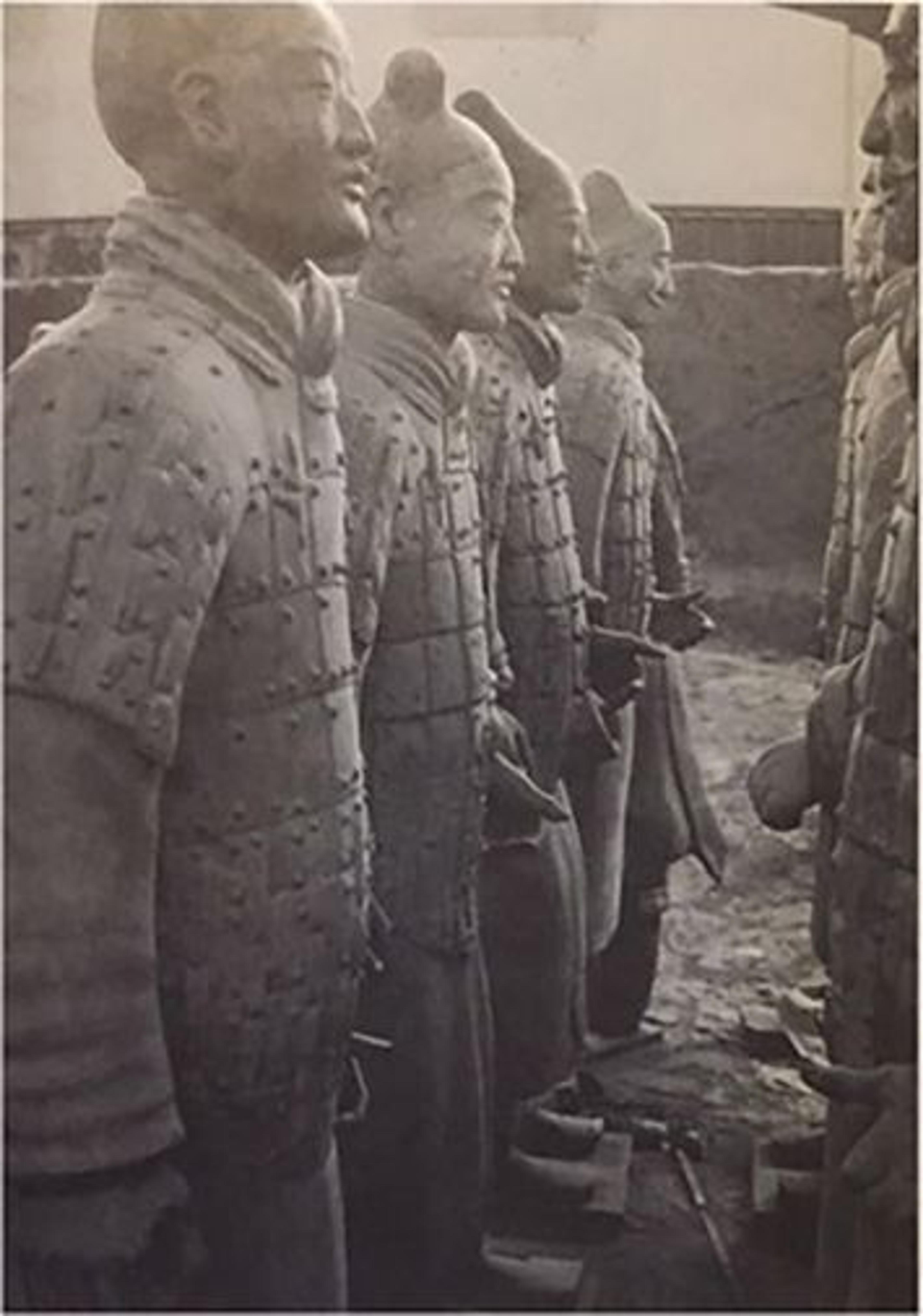

When a viewer first steps into the galleries of Age of Empires: Chinese Art of the Qin and Han Dynasties (221 B.C.–A.D. 220), he or she comes face-to-face with four life-size ceramic warrior figures with distinctive postures. Beyond the statues, one can see the silhouettes of many more armored warrior figures receding into a dark background, inviting the viewer to picture an army of thousands of sculptures of this kind. Some warrior figures even appear to be headless, simulating what one might have found at the army pits of the First Qin Emperor (Qin Shihuangdi) in Xi'an, China.

Terracotta army, pit no. 1, mausoleum complex of Qin Shihuangdi (d. 210 B.C.), Lintong (Xi'an), Shaanxi Province, China. Qin dynasty (221–206 B.C.). Photo by Maros Mraz, 2007. Photo via Wikimedia Commons

The pits of terracotta warrior figures were discovered by accident in 1974, when local farmers were sinking a well.[1] They are located about 1,500 meters east of the mausoleum of the First Qin Emperor and belong to the outer ranges of the mausoleum's burial complex. Of the four principal seven-meter-deep pits, pit no. 1 is the largest: it measures about 210 by 60 meters and features 11 parallel corridors containing more than 3,000 terracotta figures.[2] Arranged in military formation, these figures were intended to serve as the grand army for the underground imperial palace. The curatorial team's attempt to suggest the original context of the terracotta army at The Met recalls Qin Shihuangdi's ambition to create a microcosm of his empire that would extend its glory and magnificence into the afterlife.

Because of the unprecedented scale of the army created by the First Qin Emperor and, according to some researchers, the stereotyped faces of the warrior figures, most scholars believe that these statues were not modeled after living soldiers.[3] Instead, some have argued, the sculptures, or at least parts of them, were mass-produced using molds. With that in mind, and supported by my intern supervisor Maya Valladares, I started conducting research, hoping to find resources related to the step-by-step procedure of making these terracotta statues. In particular, I was interested in the components of the clay used to make these figures, the specific technique applied in different stages, and the secret of keeping the hollow statue intact throughout the construction process. However, although there are elaborate descriptions of how the warriors' headdresses and clothes suggest their ranks or positions, discussions of the actual making process and the materials used are more limited.

Two earthenware figures excavated at the mausoleum complex of Qin Shihuangdi (d. 210 B.C.), Lintong (Xi'an), Shaanxi Province, China. Qin dynasty (221–206 B.C.). Left: Figure of civil official, excavated 2000, pit K0006. Earthenware, H. 83 5/8 in. (212.4 cm). Lent by Emperor Qinshihuang's Mausoleum Site Museum. Right: Figure of unarmored general, excavated in 1978, pit no. 1. Earthenware, H. 77 1/2 in. (197 cm). Lent by Emperor Qinshihuang's Mausoleum Site Museum. Both objects are on view in Age of Empires

We learn, for example, that a peaked cap signifies a civil official of the eighth or higher rank, and that a cap with a flat rectangular front split into two folded peaks is usually worn by a general.[4] But when it comes to understanding how the Qin warrior figures were made, opinions vary.

The account offered by Wu Hung, a professor at the University of Chicago, is perhaps the most widely accepted.[5] In his book on Chinese sculpture, Hung explains that the statue was produced by making the head, hands, and torso separately, then assembling them. While the head and hands were fashioned with molds, the torso was modeled by hand. Especially important, in his view, is the retouching of the warrior figure: after the rudimentary form of each part of the body was modeled or molded with a coarse and sandy clay and had dried slightly, layers of finer clay were applied so that craftsmen could carve the details of hair, beards, eyes, mouths and chins, muscles and tendons, collars, pleats, belts and belt hooks, leg bindings and armor plates, and so forth. Only after such modeling and carving was the entire figure mounted on a base and fired.

While Professor Wu maintains that the torso was modeled by hand, Zhixin Jason Sun offers a somewhat different view in his catalogue essay for Age of Empires.[6] Sun argues that the heads, torsos, and limbs of the warriors were all cast as separate modules, then joined together with clay; clay was then also applied to the surface to allow individualization and refinement before being painted to evoke the appearance of skin, hair, clothes and arms. Zhang Wenli, a researcher at the Qin Shihuangdi Mausoleum Site Museum in Xi'an, offers a third explanation.[7] According to him, the legs and lower part of the warrior body were modeled from a solid lump of clay; then the upper torso was added using a coiling technique in which clay is rolled into a long strip and layered one coil on top of another. While the other two scholars propose a three-body-part assembly method, Zhang argues that the arms, hands, ears, and heads were made separately from different molds, and even that sometimes two molds were used for the heads. The two parts of the head and the ears were then joined and finished off by hand, and the whole figure was fitted together and fired in a kiln.

To what degree the statues were modeled or molded appears to be one of the main points of contention, yet the three leading scholars in the field of ancient Chinese sculptures mentioned above all agree that the warrior figures were constructed by joining body parts together before they were fired. However, since Mandarin is my first language, I have been able to find more resources that discuss the making process. To my surprise, an article that documents a reconstruction project carried out by archeologists and conservators in Xi'an back in 1992 draws a conclusion that is the opposite of the mainstream propositions listed above. Instead of supporting the theory that the statues were constructed section by section, the researchers in Xi'an proclaim that the whole warrior body was made in one piece, and only the head could be lifted off. They arrived at this conclusion by reconstructing the warrior figures of the Qin dynasty from preparation of the clay to the final firing stage. This reconstruction process took about a year to complete, and it was very important to keep the moisture and temperature of the inside and the outside of the statue as even as possible throughout the whole process. Unfortunately, this finding could not be published in mainland China at the time due to government restructuring, but the researchers managed to publish it in Xiongshi Meishu, a Taiwanese publication, in 1994.

Since the text is not available in English, I've outlined the authors' principal findings below. They conclude that the Qin dynasty craftsmen followed these six steps:[8]

1. Preparing the Clay

The researchers mixed local yellow earth with grit. To ensure the evenness of the inner structure of clay, they stirred the mixture and immersed it in water while constantly beating it. Then they stored the prepared clay within containers to keep it moist for future use.

2. Building the Statue

The researchers made the statue by coiling clay strips, which explains why it is hollow. No armature was found inside the torso; the statue kept its balance with its own weight. The researchers speculated that some external support, such as linen or clay, might have been used to make sure that the body would not fall over during the building process.

After they had made the feet, they only added about 10 cm per day. The researchers paid special attention to the inner shape of the statue, since the center of gravity would shift as they added more bulk. Therefore, they used wooden sticks to beat the inside of the figure throughout the process. This made the clay body denser, removed air bubbles, and roughened the surface, so that when cracks appeared, they would not reach the innermost part.

The researchers argue that there were two possible methods for constructing the arms. They believe that the arms could have been made from the bottom up and built simultaneously with the torso, then closed up when they arrived at shoulder level. Or, the arms might have been extended after the torso was complete. Accordingly, the builders used the coiling technique to attach smaller clay strips next to the torso, and closed up the arms and the torso when they reached the same level.

3. Carving the Details

The researchers used both an addition and a subtraction method for carving details. They also used bamboo strips to smooth the surface at this stage.

4. Drying Process

During the lengthy process of drying the figures in the shade, the researchers applied dampened fabric on the surface of the statue to keep the clay plastic.

5. Making the Head

Again, the researchers used the coiling technique, but they applied a second layer of clay on top of the base, so that they could carve the facial details.

6. Firing Process

The researchers constructed the kiln inside the mausoleum site itself. The kiln can fit four reconstructed warrior statues at the same time. The weight of each statue was between 150 and 200 kg, and it took about six to 10 hours to fire the whole body evenly at over 1652° F. Sometimes the head was put on the body while firing and sometimes it was fired next to the body, depending on the weight of the head.

Left: Reconstructed warrior figures, from《秦俑全真复制研究及理论思考》("A theory about the construction of the Qin terracotta figures based on research and reconstruction"), Xiong Shi Mei Shu, 1994. Photo by Sun Wei

The researchers in Xi'an learned from the failed reconstruction experiments performed by other archeological teams and successfully reconstructed terracotta warrior figures for the very first time by making the clay body in one piece. They used techniques that may well have been employed by the craftsmen in the Qin dynasty, and fired each body as a whole. More importantly, through a destructive testing of a reconstructed terracotta head, they discovered that its fragments were very similar to those found at the archeological site of the Qin mausoleum, which confirmed their hypothesis. Although they hold a different position from the other three scholars who believe the terracotta figures were made by assembling several body parts, all of them agree that a second layer of clay was applied for carving more details.

Fascinated by these findings, I started to read more articles about the Qin mausoleum. Art historians, artists, archeologists, anthropologists, and conservators all have their own respective interests while examining the same object, but some of the questions they are interested in are the same. Were the warrior figures made in one piece or by joining different body parts? Are the warrior figures portraits of individual soldiers, or representations of a single idealized form? Were they mass produced or crafted individually? The experimental archaeology project at Xi'an offers a unique explanation of how the figures were made. The project not only incorporates textual evidence and on-site investigation, but also starts with the core value of craftsmanship. The fact that the reconstructed warrior figures are hard to distinguish from the original ones, and the similarity between the fragments of the destructive testing and those found in the Qin mausoleum, makes this unique "one-piece" theory about making the warrior even more convincing.

I will be continuing my research at The Met, this time under the tutelage of Vicki Parry in the Department of Objects Conservation, to gain more insights into the technology of ceramic production and the conservation of these ceramic objects. Hopefully I will be able to share more interesting stories with you by the end of the summer!

Notes

[1] Wu Ying, ed., Atlas of World Heritage: China (San Francisco: Long River Press; Shanghai: Shanghai Press and Publishing Development Company), 148.

[2] Frances Wood, "Seas of Mercury, Pearl Stars, and an Army of 8,000 Men," China's First Emperor and His Terracotta Warriors (New York: St. Martin's Press, 2008), 131.

[3] Ladislav Kesner, "Likeness of No One: (Re)presenting the First Emperor's Army," The Art Bulletin 77, no. 1 (1995): 115. doi:10.2307/3046084.

[4] Zhixin Jason Sun, Age of Empires: Art of the Qin and Han Dynasties (New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2017), 80–82.

[5] Hung Wu, Chinese Sculpture (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2003), 61.

[6] Zhixin Jason Sun, Age of Empires: Art of the Qin and Han Dynasties (New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2017), 6, 80.

[7] Zhang Wenli, The Qin Terracotta Army: Treasures of Lintong (London: Scala Books, 2006), 72.

[8] Yixian Sun and Wei Sun,《秦俑全真复制研究及理论思考》("A theory about the construction of the Qin terracotta figures based on research and reconstruction"), Xiong Shi Mei Shu, 1994.

Related Links

Age of Empires: Chinese Art of the Qin and Han Dynasties (221 B.C.–A.D. 220), on view at The Met Fifth Avenue through July 16, 2017