Left: fig. 1. Armor of Henry II of France (reigned 1547–59), ca. 1555. French, possibly Paris. Steel, silver, gold; H. 74 (187.96 cm); Wt. 53 lb. 4 oz. (24.20 kg). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Harris Brisbane Dick Fund, 1939 (39.121a–n). Right: fig. 2. Attributed to Étienne Delaune (French, 1518–83) or attributed to Jean Cousin the Elder (French, ca. 1490–ca. 1560). Design for the Right Pauldron of a Parade Armor, ca. 1555. French, Paris. Pen and ink with watercolor wash on paper; Greatest length, 10 in. (25.4 cm) greatest width, 6 17/32 in. (16.6 cm) shortest width, 3 47/64 in. (9.5 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Rogers Fund, 1954 (54.173)

The exhibition Arms and Armor: Notable Acquisitions 2003–2014 includes various works on paper, which call our attention to many features of the design of weapons and battle dress, and elucidate how they performed important functions beyond the confines of the battlefield.

«In his 1583 book The Anatomie of Abuses, the English moralist Phillip Stubbes criticized the growing trend for wearing arms as a stylish accessory, condemning upstart fops who sported "swoords, daggers and rapiers guilte and reguilte, burnished, and costly engraven, with all things els that any noble of honorable, or worshipfull man doth, or may weare so as one cannot easily be discerned from the other." Stubbes's main concern lay in the fact that men of all classes gave in to the whims of fashion and started wearing decorated arms daily as pieces of jewelry, giving way to vanity and pride and simultaneously blurring the lines of social standing.»

The tradition of decorating arms and armor according to the latest styles and fashions was not new in Stubbes's day, but is as old as the existence of martial objects in cultures around the world. It flourished and became particularly lavish in Europe from the fifteenth century onward; not only worn on the battlefield, but also as part of a gentleman's daily attire, weapons and specific pieces of armor gained the additional function of impressing onlookers, and conveying meaning through personalized imagery and ornament. A suit of sixteenth-century parade armor belonging to Henry II of France provides a particularly spectacular example of this elaborately crafted, glamorous, and personalized martial apparel (figs. 1, 2). His initial "H", as well as several crescent moons, the emblem of his mistress Diane de Poitiers, are embedded in a dense web of tendrils and grotesques with small figures drawn from classical mythology. The great artistry involved in creating attire like this marked the owner's status as a learned man of great power, wealth, and taste.

Armorers, smiths, sword, and gun makers not only had to concern themselves with form and functionality, but also had to stay abreast of the latest trends in both ornament and technology. As fashionable status symbols, guns, armor, and swords spoke not only to the owner's readiness and ability to fight, but also demonstrated his awareness of cosmopolitan artistic vogues and innovations in armor linked to military strategy.

From the sixteenth century onward, ornament prints—etchings and engravings containing design ideas—became an important auxiliary tool in the production of fashionable and sophisticated weapons. These loose sheets and series fulfilled the double function of providing prolific designers with a podium to share their ideas, and serving as a source of inspiration for others to come up with new designs for their own commissions.

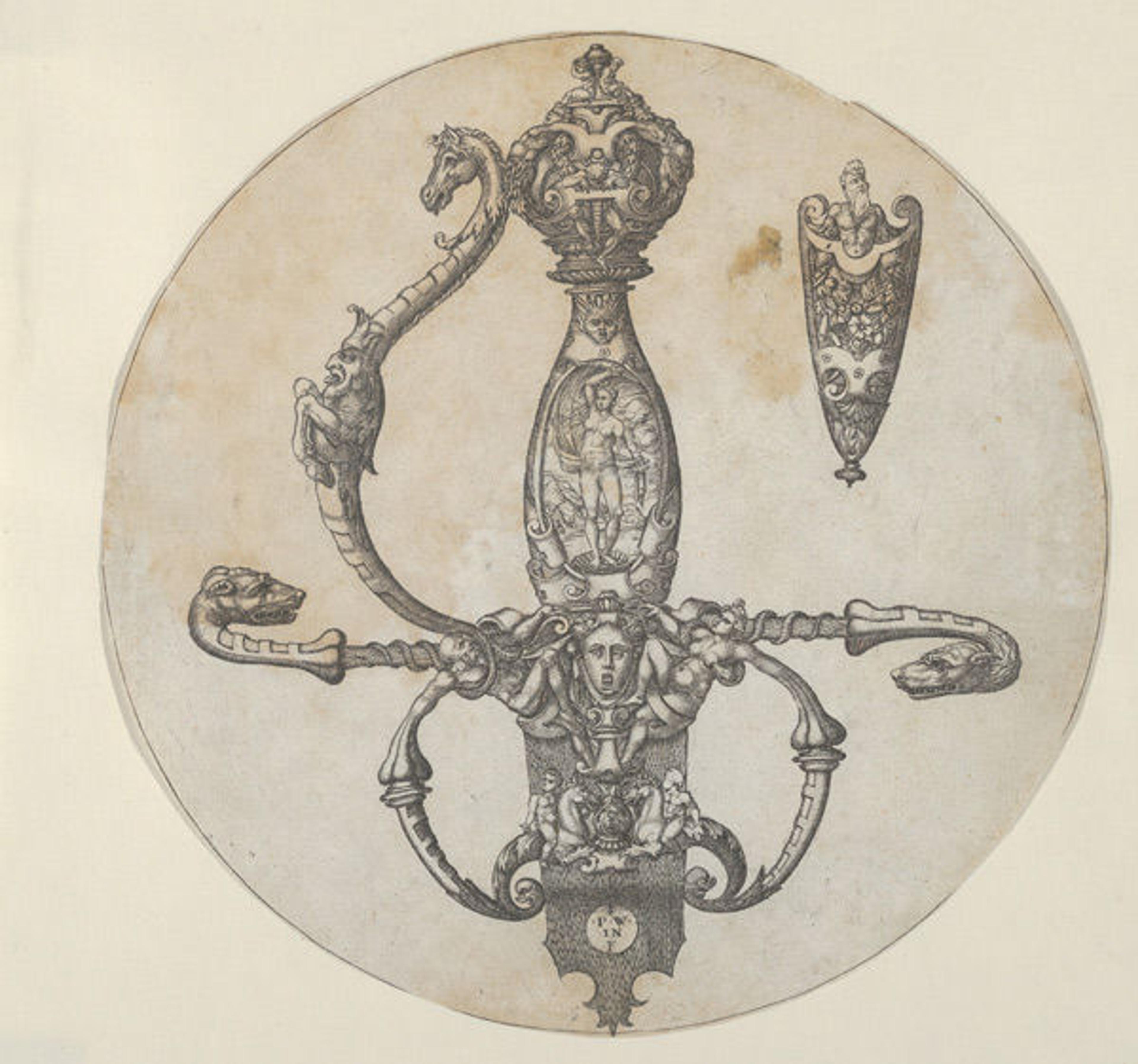

Fig. 3. Pierre Woeiriot (French, ca. 1531–1589). Design for a Sword Hilt, 1550–1560. Engraving; Sheet: 7 5/8 x 7 11/16 in. (19.3 x 19.6 cm) [diameter]. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, The Elisha Whittelsey Collection, The Elisha Whittelsey Fund, 1949 (49.20.12)

Due to the similarities between the techniques of printmaking and the decoration of arms and armor (which both rely on the manipulation of a metal plate), designs in this field can be found among the earliest ornament prints (fig. 3) and a steady production continued through the nineteenth century. They form an important repository of information about the design history of arms and armor and, for this reason, are collected by the Museum. Examining these prints in combination with extant design drawings provides a rich lens through which to consider the artistic and cultural significance of weaponry in the early modern era. These works on paper not only speak to processes of design, but, due to the detailing intrinsic to their production, also draw attention to the rich and manifold ways in which arms and armor demand and reward close looking.

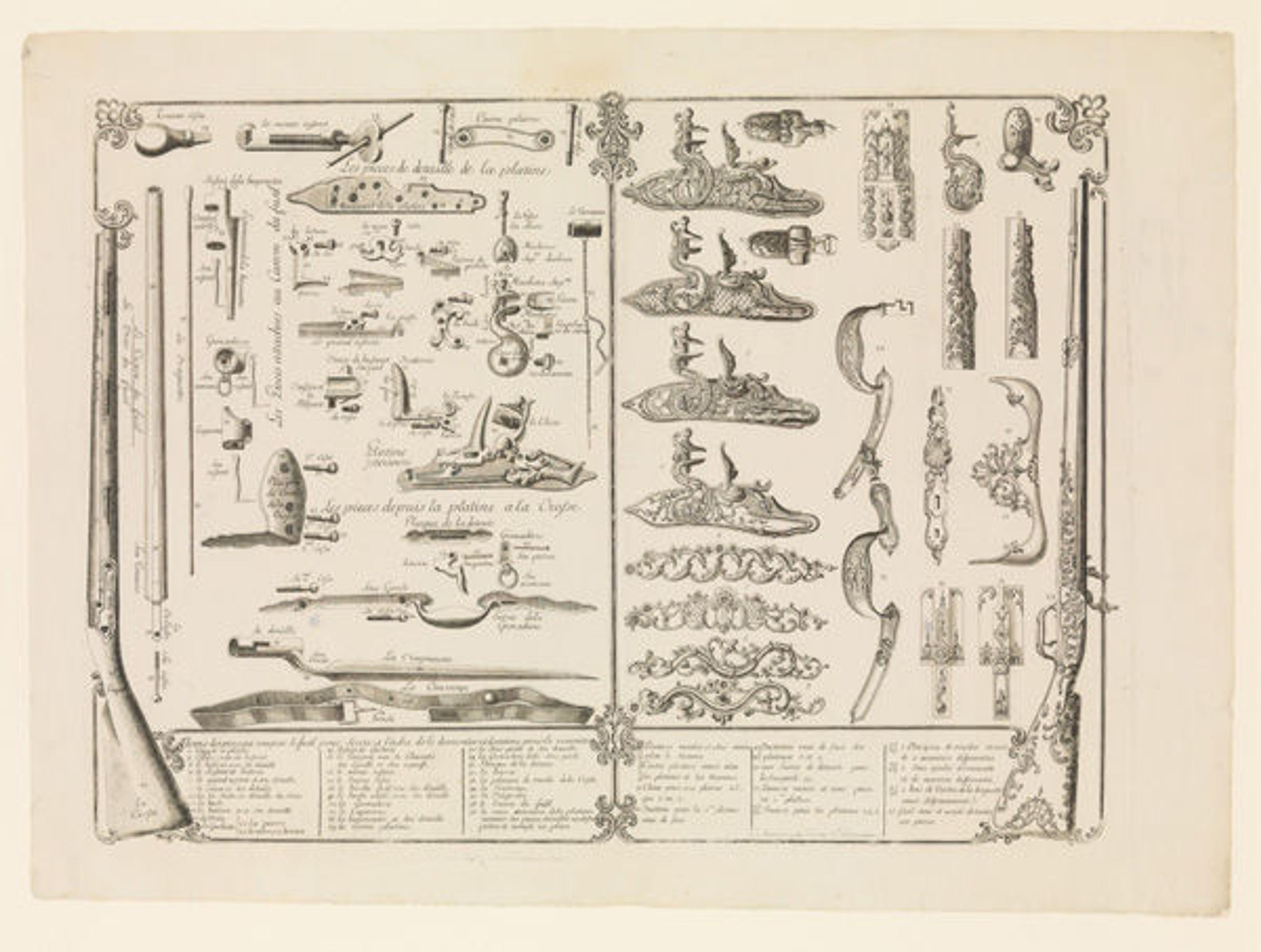

Fig. 4. Perrier (French, active mid-18th century). Engraving of Firearms Parts, ca. 1750. French, Strasbourg. Ink on paper; L. 25 1/4 in. (64 cm); H. 18 3/4 in. (47.5 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, Jonathan and Elizabeth Roberts Gift, 2004 (2004.57)

A mid-eighteenth-century print, sold by a print vendor named Perrier (fig. 4), shows the parts of two flintlock guns in great detail. The stocks of a standard musket and a more elaborate hunting gun are shown in their entirety on either side of the print and form part of the decorative framework. Inside the frame, as if dissected, the individual parts of the disassembled weapons down to the screws and straps are systematically represented, with labels and numbered inscriptions further identifying each part in detail. The print conveys practical information to potential users and collectors of the weapons, or craftsman who could simultaneously see how to assemble and decorate a flintlock gun.

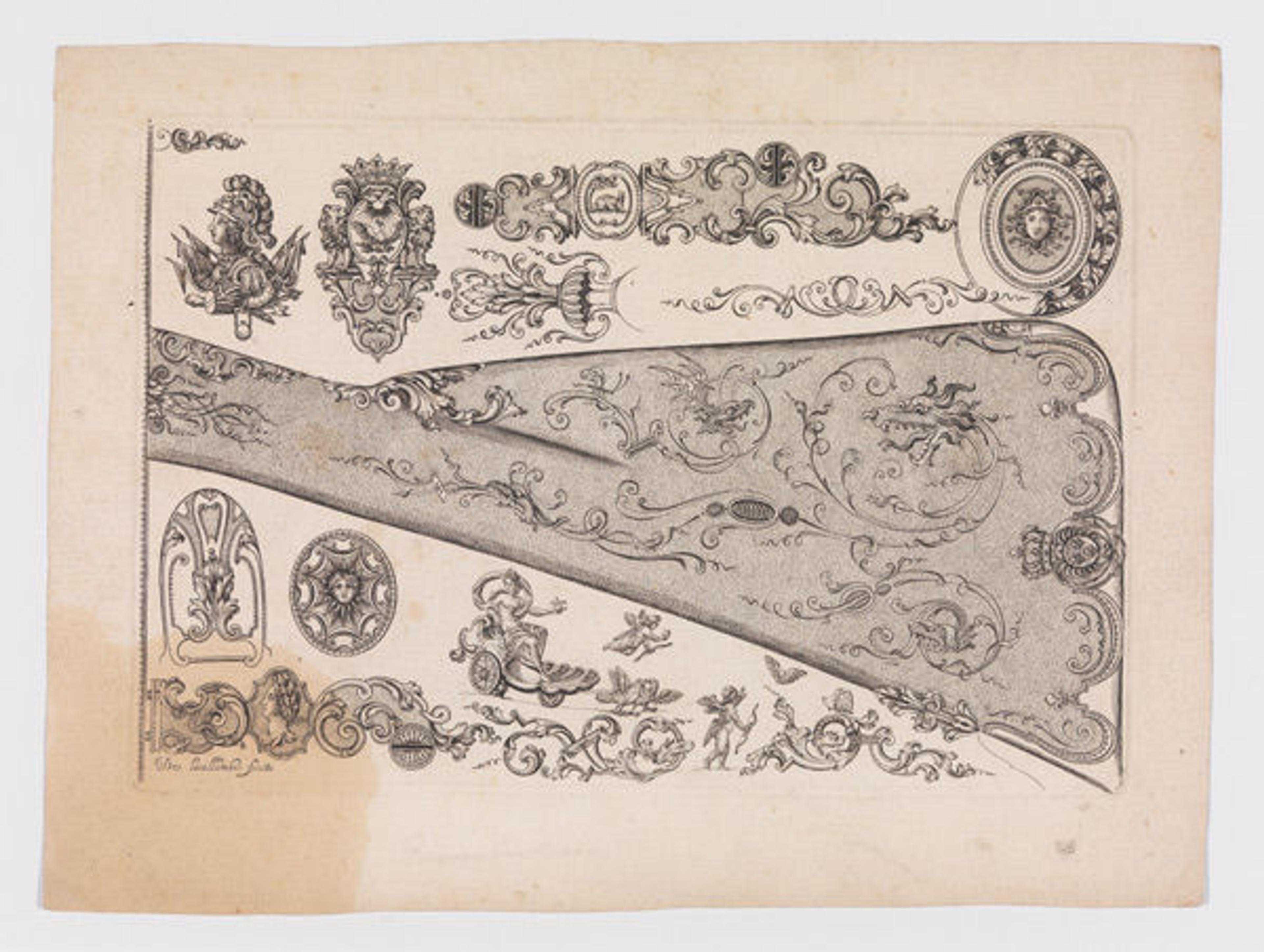

Fig. 5. De Lacollombe (French, active ca. 1702–ca. 1736). Print from Nouveaux Desseins D'Arquebuseries, ca. 1705–30. French, Paris. Ink on paper; 11 x 8 1/4 in. (27.9 x 20.9 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, Bequest of Stephen V. Grancsay, Rogers Fund, Helmut Nickel Gift, and funds from various donors, by exchange, 2013 (2013.907)

However, in print series like Nouveaux Desseins D'Arquebuseries (fig. 5) by the French engraver De Lacollombe, we can see some more of the complex ways in which the production of printed ornament and arms informed one another. In the various plates of the series, ornament is applied to particular parts of pistols and long arms. The use of fine stippling, together with linear ornamental patterns, vividly suggests how working the surface with specific tools and using gold or silver wire inlay could enhance a metal or wood substrate. In other examples, the ornament is not anchored to specific gun parts, giving license to the gun makers and other craftsmen to be combined and rearranged freely. Rather than restricting design options, these prints can be seen as both demonstrating the artistic ingenuity of the printmaker and serving as a creative inspiration for gunsmith, gun stocker, steel chiseler, and other craftsmen.

Left: fig. 6. Rudolf Franz Ferdinand von Talmberg (Bohemian, ca. 1645–1702). Album of Bit Designs, 1674. Bohemian. Ink on paper; covers: 14 1/2 x 9 3/4 in. (36.8 x 24.8 cm); sheets: 14 1/4 x 9 1/2 in. (36.2 x 24.1 cm); plates: approximately 12 1/4 x 4 in. (31.5 x 10 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Vivian Lam Gifts; and Bequest of Stephen V. Grancsay, Rogers Fund, Helmut Nickel Gift, and funds from various donors, by exchange, 2013 (2013.590). Right: fig. 7. Bit, ca. 1575–1625. Possibly Italian. Iron, gold, silver, copper alloy; 12 x 8 1/2 in. (30.5 x 21.6 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, Kenneth and Vivian Lam Gift, 2006 (2006.44)

This characteristic also comes to the fore when we compare prints in Album of Bit Designs by Rudolf Franz Ferdinand von Talmberg with an actual horse's bit (figs. 6, 7). The prints from the album present highly detailed, multifaceted designs, but they do not give specific indications for the choice of materials. The bit, made from iron, gold, silver, and copper, shows how the metalworker could translate the ornament from the prints into a variety of materials and techniques: embossing, chasing, and damascening with gold and silver. De Lacollombe and Talmberg show that while there was sometimes a direct one-to-one relationship between the models in ornament prints and the objects they inspired, in many cases the process from print to object can best be described as "creative translation."

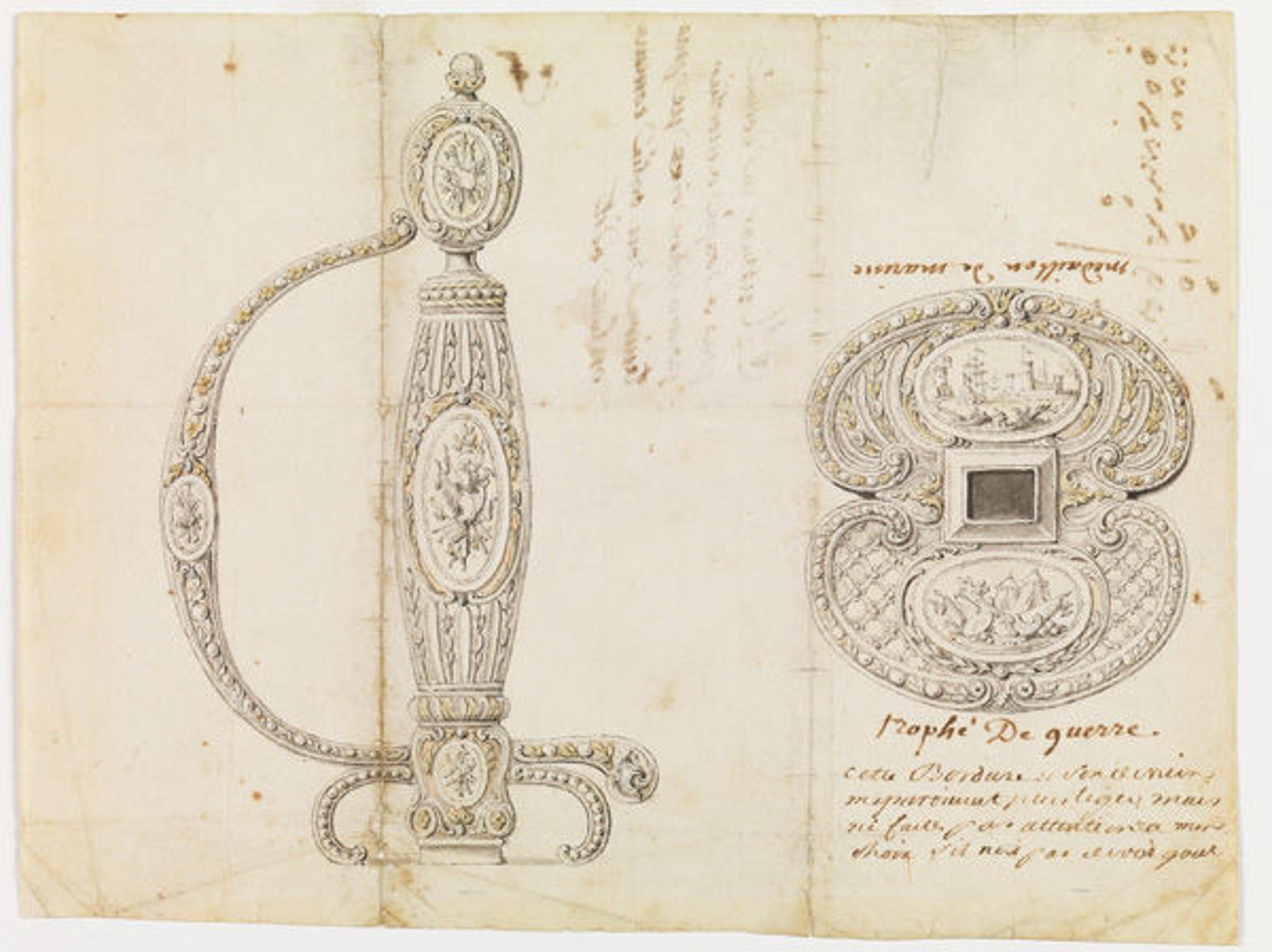

Fig. 8. Design for a Smallsword Hilt, ca. 1780. French. Pen, ink, colored wash, chalk on paper; 9 x 7 in. (23 x 17.8 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of John Blair, in memory of his father, Claude Blair, 2011 (2011.102)

A rare and beautiful eighteenth-century French design for a sword hilt (fig. 8) gives us a sense of the way in which discussions about design and style took place. The drawing contains two designs for the hilt of the sword and the shell guard. The latter is portrayed from above to reveal its lavish decoration, for which two different options are shown—the upper half contains an oval medallion with a maritime scene, while the lower half has a similar medallion with a weapon trophy surrounded by trelliswork. An inscription below the design, directed at the client, explains that these are merely suggestions that can be altered without a problem to the client's taste. The drawings thus represents the opening of a discussion about the final design of this hilt.

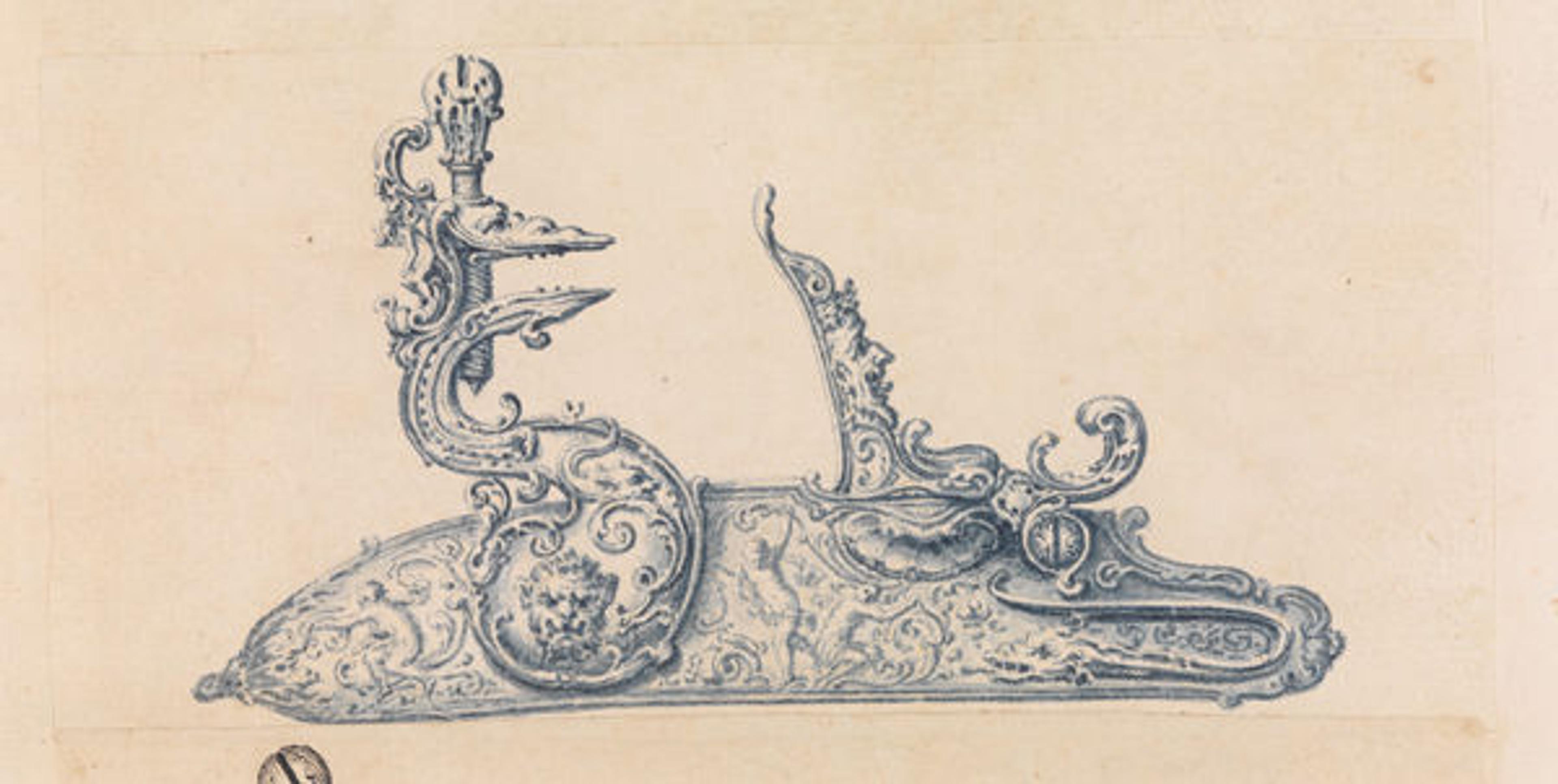

Fig. 9. Drawing from an Ornament Scrapbook: A Flintlock Gun Lock, 18th century. Probably French. Pen, blue ink, and blue wash; 7 9/16 x 3 5/8 in. (19.2 x 9.2 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, Arthur Ochs Sulzberger Gift, 2011 (2011.308)

Looking closely at the details of the decoration also demonstrates that ornament not only served as embellishment, but could speak to more exalted themes. The decorations, for example, frequently include fantastical beasts such as fire-breathing dragons and grotesque monsters. These elements were often cleverly applied to parts of the weapon that actually triggered the sparks that caused the gunpowder to light and "fire" the bullet; the eighteenth-century drawing of a gunlock, shown below, demonstrates such witty and complex decorations (fig. 9). The top of the lever, called the cock, takes the shape of the head of a reptilian-like, grotesque monster whose jaws are also the mechanical jaws that clasp the piece of flint which ignites the gunpowder inside the gun barrel. A serpent spewing flames mimics the mechanism of the nearby frizzen spring. Thus, mechanical ingenuity finds expression in an ornamental language that embodies the weapon's circuitry in various modes of figurative and decorative representation. These playful design elements indicate the degree to which each detail of a weapon or suit of armor was carefully calibrated to invite, impress, surprise, and even enchant those who ventured to take a closer look.

While looking at the ornament on a weapon may seem, at first, to be a superficial exercise, it exposes us to the close relationship between artistry and weaponry that existed until the very end of the nineteenth century. Weapons were not just functional, but were also an important means of representation, and it is especially the decoration that, on various levels, attest to this fact. Moreover, works on paper, whether drawings or ornament prints associated with arms and armor, played an important role in the development and circulation of artistic ideas and innovations, and were essential to the professionals and patrons who wished to be at the proverbial "cutting edge" of fashion.