The current exhibition Pastel Portraits: Images of 18th-Century Europe opens a window on one of the most popular art forms of the Rococo and Enlightenment eras. These works slipped from public notice long ago as they became associated with the artificiality of the ancien régime, and in modern times because their fragility discouraged exhibition and travel. This is the first exhibition of such portraits in at least seventy-five years. It presents a sense of the great numbers of artists who practiced in this once popular medium, the many different styles in which they worked, and the materials and techniques they employed.

The rise of pastel in the eighteenth century

The widespread interest in portraits in pastel throughout eighteenth-century Europe was sparked in Paris in 1720–21 by the visit of the Venetian pastelist Rosalba Carriera (1673–1757), the guest of the influential collector and connoisseur Pierre Crozat. Many factors contributed to the resounding reception of the medium at that time and over the next decades. Among them was a new, prosperous buying public—the aristocracy and wealthy financiers who, with Louis XV, began to leave Versailles in about 1715 and established themselves in opulent Parisian hôtels particuliers (urban private homes). To decorate the walls of the small rooms of these luxurious homes they turned to the newly fashionable intimate paintings by seventeenth-century Dutch and Flemish artists, contemporary drawings in gouache and red chalk, and their own likenesses, which they commissioned in pastel.

Whereas portraits in pastel were known in the previous century, by 1700 the ready availability of cast plate glass made it possible for these powdery compositions, always requiring surface protection, to be executed on a scale comparable to easel painting, a feature that would contribute to their growing prestige. Pastel's capacity to imitate, if not surpass, the effects of oil led contemporary viewers to regard these works as aesthetically comparable. Many pastelists—such as Rosalba Carriera, Maurice Quentin de La Tour (French, 1704–1788), Élisabeth Vigée Le Brun (French, 1755–1842), Francis Cotes (English, 1726–1770) and John Russell (English, 1745–1806)—were accepted into their country’s academy or appointed as pastelists to royalty, a testament to the high regard in which the medium was held.

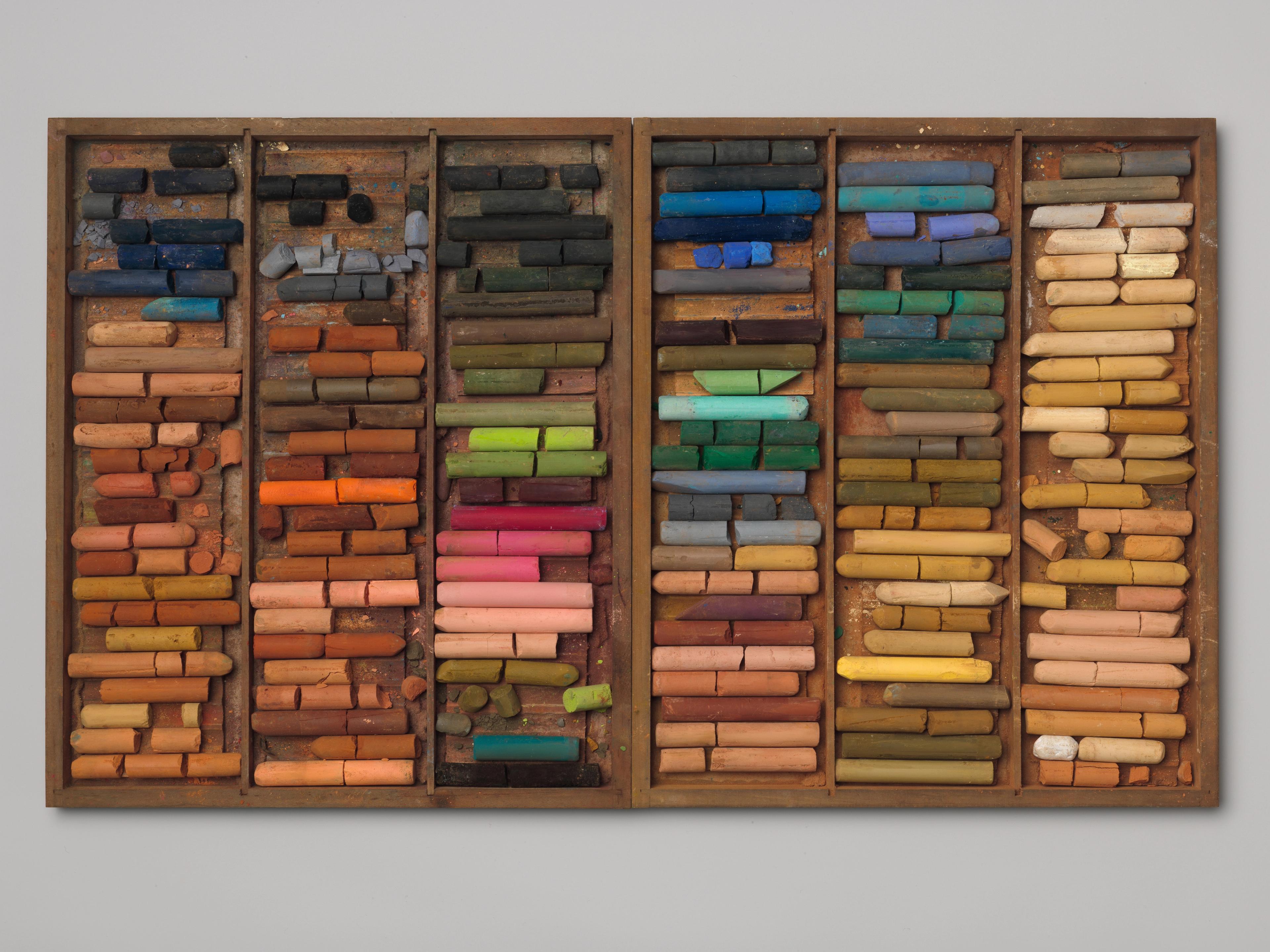

The emergence of crayon-makers in cities throughout Europe also played an important role in nurturing the portrait market among both the elite and the less affluent. The growth of this trade occurred as artists gained in status and delegated the menial tasks of their work to artisans; for pastelists, such specialists undertook the production of high-quality crayons in varied textures in a limitless range of hues. Portraits in these readymade crayons offered tangible advantages over oil for the artist and the sitter: they required fewer sittings as there was no drying time; less paraphernalia; the materials were easily portable and the costs were lower. These factors generated much competition with oil painters in the academy and in the marketplace.Economic and social changes underlying the rising popularity of pastel were supported by the pervasive Enlightenment spirit that promoted the theoretical ideas of the century as well as inventions and discoveries that would contribute to the improvement of commerce and the artisanal trades, many of which were illustrated in the Encyclopédie edited by the French writer and philosopher Denis Diderot (1713–1784). New products, such as pigments, quality crayons, paper, and fixatives emerged in this climate.

What makes up a pastel?

The basic constituents of pastel are a pigment, a filler (a white mineral which serves to give opacity and body), and a binder (a weak adhesive) that loosely holds the two powdery substances together so that they may be formed into a crayon for use. In the eighteenth century, the ideal crayon was to be sufficiently firm so it could be grasped between the fingers without breaking, yet powdery and soft enough to crumble when stroked across a support. A relatively small range of pigments (mostly the same as those used for oil painting) was used in forming an innumerable array of colors, a feature of the medium still characteristic of today’s pastel box. These pigments were combined to produce the desired hue, with proportional amounts of filler added to produce the tints. This multitude of hues allowed pastelists to work in gradations of tone rather than in color mixtures so as to produce the greatest brilliance.

The process of fabricating pastels in the eighteenth century was complex. Many steps had to be carried out by hand and were varied according to the composition of the color, starting with the preparation of the pigment by grinding and washing. Because pigments have distinctive properties (such as cohesiveness, softness, brittleness), each had to be coordinated with a particular filler (selected from a range of materials, such as chalk, tobacco pipe clay, gypsum, and alabaster) and a suitable binder (among them, gum tragacanth, oatmeal whey, or skim milk) to produce crayons of satisfactory texture. After the ingredients were mixed together the paste was divided and rolled into crayons, cut to length, and carefully dried by air or with heat to avoid imperfections and cracks.

A distinctive brilliance

Pastel was praised in the eighteenth century because of the lifelike quality, or "bloom," it conferred upon its subjects. This distinctive appearance results from the physical characteristics of the medium and the way in which it reflects light. As all powders, pastel reflects light from the facets of its finely divided particles and the air spaces in between them, an effect evoking a sense of white light. In pastel this powder is composed of numerous particles of pigment and filler. Because there is only a minute amount of binder, and the powder is opaque, light does not penetrate through pastel (as it does through a varnished oil painting) but is diffusely scattered, or reflected, from the surface. This physical phenomenon accounts for its velvety, matte quality. Additionally, the absence of a varnish, which inevitably alters in color over time, accounts for the characteristic brilliance and purity of tone of pastels. This visual property was especially prized by the eighteenth-century connoisseur and consumer who similarly took delight in the bright, scintillating surfaces of contemporary interior décor, as evidenced by the profusion of mirrors, ormolu mounts and ornaments, and gilt frames popular at the time.

Pastel’s characteristic light can be impaired when a fixative is applied to a composition. Because the surface of a pastel is easily rubbed and damaged, many recipes for protective substances were devised in the eighteenth century, some even claiming to provide a means of enabling these works to be cleaned or varnished. There was, nonetheless, great debate as to their efficacy, as it was recognized that applying a resin to the surface of a pastel would darken the colors and cause them to yellow. Instead, to secure the powder to the support, artists depended upon using slightly roughened paper and careful building of the layers of color.

Executing pastels

Compared to oil painting, pastels required less time and fewer tools, but the application of the colors was complex and making corrections was difficult. Pastels are most often executed on paper, though vellum was occasionally used for portraits of royal sitters, such as those by Jean Étienne Liotard (Swiss, 1702–1789). The paper used was usually the same type made for wrapping objects; it was relatively strong and coarse and thus well suited to withstand rubbing with pumice, a technique that artists used to produce a weak bond, or tooth, to hold the pastel powder to the support. These papers were generally blue (the color was rarely left visible because the sheet was fully covered with pastel) and they were mounted on canvas tacked to a strainer to provide a good working surface.

The tools of the pastelist were basic, the most important being stumps, or tight spirals of paper or leather—or simply the artist’s finger—that were used to spread the pastel powder. Most portraits were executed with dry pastel, the artist either stumping or “sweetening” the color into smooth continuous masses without ready evidence of individual strokes, as in the example of Jean Marc Nattier’s portrait of Madame Royer, or with a network of discrete strokes that the eye would optically blend, as in Jean Baptiste Greuze’s portrait of Baptiste aîné.

Many artists also incorporated wet techniques: either using pastel powder mixed with water or a gum and applying it by brush or blending it with the finger (as in Rosalba Carriera’s Young Woman with a Pearl Earring) or wetting the tip of the pastel and applying it thickly to create an impasted effect comparable to oil, as seen in the lace details of John Russell’s Portrait of Mrs. Robert Shurlock and Her Daughter Ann.

In the portrait of Lady Rushout and her children, Daniel Gardner employed a distinctive mixed-media technique using pastel for the flesh tones and watercolor and broad thick strokes of gouache for the background and clothing. The overall effect of these works, rendered as if by brush and surrounded by a gilt frame, succeeded in evoking the presence of an easel painting.

Safeguarding pastels

Some pastel colors—such as carmine, which was used to evoke the hue of the sitter's complexion—are prone to fading, while many others have greater durability. Regardless of color, all pastels must be protected from exposure to high levels of light or prolonged periods of illumination. Unlike oils, pastels' vulnerability to fading is increased because they are not protected by a varnish, nor are the powdery components surrounded by a resin.

In most eighteenth-century pastel portraits, color extends across the entire support, but those with exposed areas of paper, such as the préparations by Maurice Quentin de la Tour, are at the greatest risk of color alteration from exposure to light. Often they have discolored and turned brown in the reserve areas. Museums generally limit the display of pastels to no more than three months per year at five foot-candles; if they are displayed for longer periods of time a light level of approximately three foot-candles should be maintained.

Pastels must always be framed and glazed to best preserve them. Most acrylic sheeting is not satisfactory to glaze pastels because its static charge will attract pastel particles, a problem that is exacerbated when the plastic is rubbed (during cleaning, for example). To protect the surface of these fragile works, shatterproof glass with an Ultraviolet (UV) barrier is recommended. Pastels are occasionally glazed with AR acrylic sheeting, but we do not yet know this material’s long-range properties (such as deleterious off-gassing, which is common to many plastics as they age and deteriorate). If a pastel is glazed with non-static acrylic sheeting, it is recommended that it be used only for the purposes of transport or loan rather than for permanent framing. A pastel that is framed with the original eighteenth-century glass, which does not have a UV barrier, can be protected from fading and color alteration by maintaining low light levels, keeping curtains drawn when the work is not being viewed, and coating nearby windows with a UV film. To prevent the entry of dust, a seal made of strips of paper should be applied to the back of a framed pastel.

Pastels must also be protected from mold and other forms of biodeterioration, problems to which they are vulnerable because of the organic binders in the crayons, the adhesives used in the mounting structure, and their paper supports. Environmental levels must be kept in a range of 68 to 72 degrees Fahrenheit and 48 to 52 percent relative humidity. High humidity can provoke staining; low levels can lead to desiccation of the support.

For travel and transport, pastels should be framed and kept in a horizontal, face-up position. One of the greatest hazards to a pastel is vibration. This can be reduced by cushioning crates with ethafoam, or, for short distances, wrapping the composition in bubble wrap with the bubbles facing outward.

Understanding the particular properties of pastel enhances our appreciation for the distinctive light and beautiful richness of color of the medium, qualities underlying its great acclaim in the eighteenth century. It also enables us to take the steps needed to preserve these fragile portraits so that we may continue to enjoy them and ensure their future in good condition.