Fig. 1. Frog pendant, 5th–10th century. Venado Beach, Panama. Gold (cast), black core; H. 2 3/4 x W. 3 3/4 x D. 1 7/8 in. (7 x 9.5 x 4.8 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, The Michael C. Rockefeller Memorial Collection, Bequest of Nelson A. Rockefeller, 1979 (1979.206.1350)

«In 1948, the United States Navy discovered a rich Precolumbian cemetery with a bulldozer in the target shooting area of Fort Kobbe, a former military installation within the Canal Zone of Panama. In early 1951, after "a great deal of unrecorded digging by soldiers," Samuel Lothrop of the Peabody Museum of Harvard University arrived and conducted systematic excavations of over two hundred burials (fig. 2). After the Harvard project ended, "weekend" archaeologists such as Neville and Eva Harte continued work at Venado Beach and dug over 150 cist-like graves. Another such couple was Lt. Col. and Mrs. Lee E. Montgomery, who excavated in August of 1951, documenting nineteen graves, some of which contained multiple individuals.»

Fig. 2. View of Venado Beach burials. Lothrop, 1954: fig. 60.

The Montgomery work was known to Lothrop, who published some of their finds in his 1956 article "Jewelry from the Panama Canal Zone." In the archives of the Museum of Primitive Art, now held at The Metropolitan Museum of Art, a note from Lothrop to Montgomery on November 7, 1951, indicates his receipt of the photos from their recent excavations. In the article he describes the context after receiving "data and photographs" from both the Hartes and Lt. Col. Montgomery. Until recently, it was unclear what type of data existed from the work of the Montgomery excavations.

Mrs. Montgomery sold two gold frogs and two nose rings to the Museum of Primitive Art in 1971. Also part of the transaction was a small notebook that entered the museum's archives containing the original 1951 field notes and drawings of the burial excavations by the Montgomerys. It must have been the information that Lothrop consulted, as it contains detailed diagrams of where the Met's works came from, as well as works now likely in the collections of the Art Institute of Chicago and Dumbarton Oaks (fig. 3).

Fig. 3. Left: Combined-figure pendant, 700–1000 CE. Coclé, Panama. Gold; H 6.15 x W 5.18 x D 4.13 cm (2 7/16 x 2 1/16 x 1 5/8 in.). Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection, Washington, D.C., Pre-Columbian Collection (PC.B.372). Upper right: Filigree pendant in the form of a frog or toad, A.D. 500/1000. Cast gold; L. 18.26 cm (7 3/16 in.). The Art Institute Chicago, Wirt D. Walker Fund (1969.792). Center right: Nose ornament in the form of a turtle with C-shaped body, A.D. 800/1200. Spondylus shell; W. 7.3 cm (2 7/8 in.). The Art Institute Chicago, Wirt D. Walker Fund (1969.795). Lower right: Nose ornament in the form of a long-nosed Saurian with C-shaped body, A.D. 800/1200. Spondylus shell; W. 7.9 cm (3 1/8 in.). The Art Institute Chicago, Wirt D. Walker Fund (1969.794)

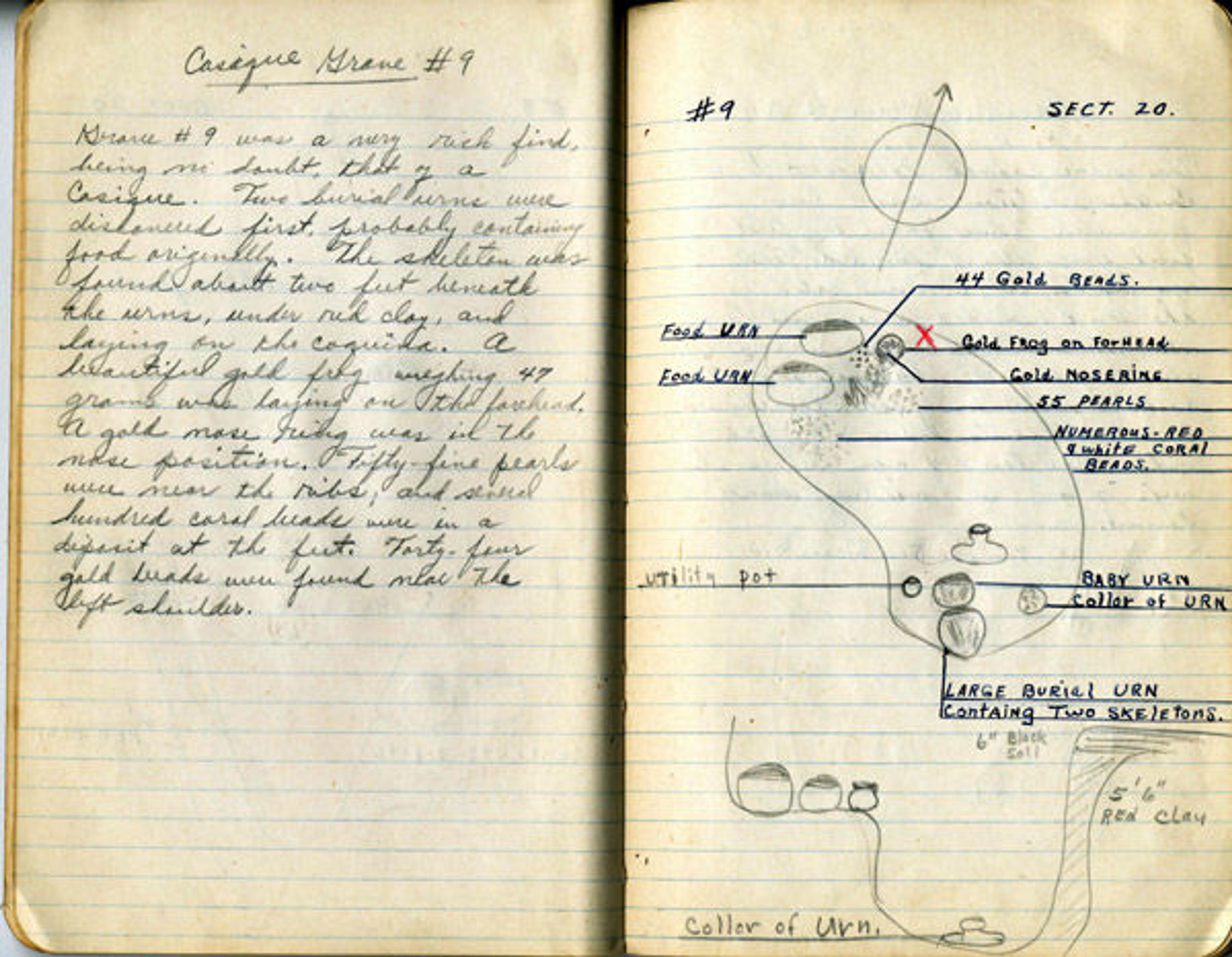

The notebook contains basic descriptions of the different burials, complete with plans and cross-section drawings. For example, the page titled "Casique Grave #9," details the deposition of a cacique (chief) on top of the underlying coquina (shell mound):

Grave #9 was a very rich find, being no doubt, that of a casique. Two burial urns were discovered first, probably containing food originally. The skeleton was found about two feet beneath the urns, under red clay, and laying on the coquina. A beautiful gold frog weighing 47 grams was laying on the forehead. A gold nose ring was in the nose position. Fifty-five pearls were near the ribs; and several hundred coral beads were in a deposit at the feet. Forty-four gold beads were found near the left shoulder.

The beads that Montgomery described as coral were undoubtedly spondylus shell—a red-orange or white marine shell commonly used in ancient Panamanian necklaces and regalia.

Fig. 4. Lee S. Montgomery, Lt. Col., "Venado Beach," 18–19. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Department of the Arts of Africa, Oceania, and the Americas Archives. View the complete notebook (PDF).

It is probable that this gold frog and nose ring noted in this entry are two of the four objects purchased by the Museum of Primitive Art from Montgomery (fig. 5). The Montgomery notes show several other gold nose rings, one of which certainly is the other one in the Met's collection (fig. 5a). One of the frogs that the Museum of Primitive Art purchased (fig. 5b) could be the "beautiful" frog that Montgomery also mentioned in his journal. The frog shown at the top of this article (fig. 1) is probably the tumbaga (copper-gold alloy) frog from Montgomery's entry about the tenth grave, noted as such for its solid casting around a core, rather than the open-work spiral design seen in the other frogs.

![Left: Fig. 5a. Nose ornaments, 5th–8th century. Venado Beach, Panama. Gold (cast); left H. 5/8 x Diam. 1 in. (1.6 x 2.5 cm); right H. 1/2 x Diam. 1 in. (1.3 x 2.5 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, The Michael C. Rockefeller Memorial Collection, Bequest of Nelson A. Rockefeller, 1979 (1979.206.1353 [left], 1979.206.1352 [right]). Right: Fig. 5b. Frog pendant, 5th–8th century. Venado Beach, Panama. Gold (cast); H. 2 1/4 x W. 1 1/2 x D. 1 1/8 in. (5.7 x 3.8 x 2.8 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, The Michael C. Rockefeller Memorial Collection, Bequest of Nelson A. Rockefeller, 1979 (1979.206.1351)](https://cdn.sanity.io/images/cctd4ker/production/4a11a399979fa42f19ee7c827aa26aa6b3f2a35b-600x292.jpg?w=3840&q=75&fit=clip&auto=format)

Left: Fig. 5a. Nose ornaments, 5th–8th century. Venado Beach, Panama. Gold (cast); left H. 5/8 x Diam. 1 in. (1.6 x 2.5 cm); right H. 1/2 x Diam. 1 in. (1.3 x 2.5 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, The Michael C. Rockefeller Memorial Collection, Bequest of Nelson A. Rockefeller, 1979 (1979.206.1353 [left], 1979.206.1352 [right]). Right: Fig. 5b. Frog pendant, 5th–8th century. Venado Beach, Panama. Gold (cast); H. 2 1/4 x W. 1 1/2 x D. 1 1/8 in. (5.7 x 3.8 x 2.8 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, The Michael C. Rockefeller Memorial Collection, Bequest of Nelson A. Rockefeller, 1979 (1979.206.1351)

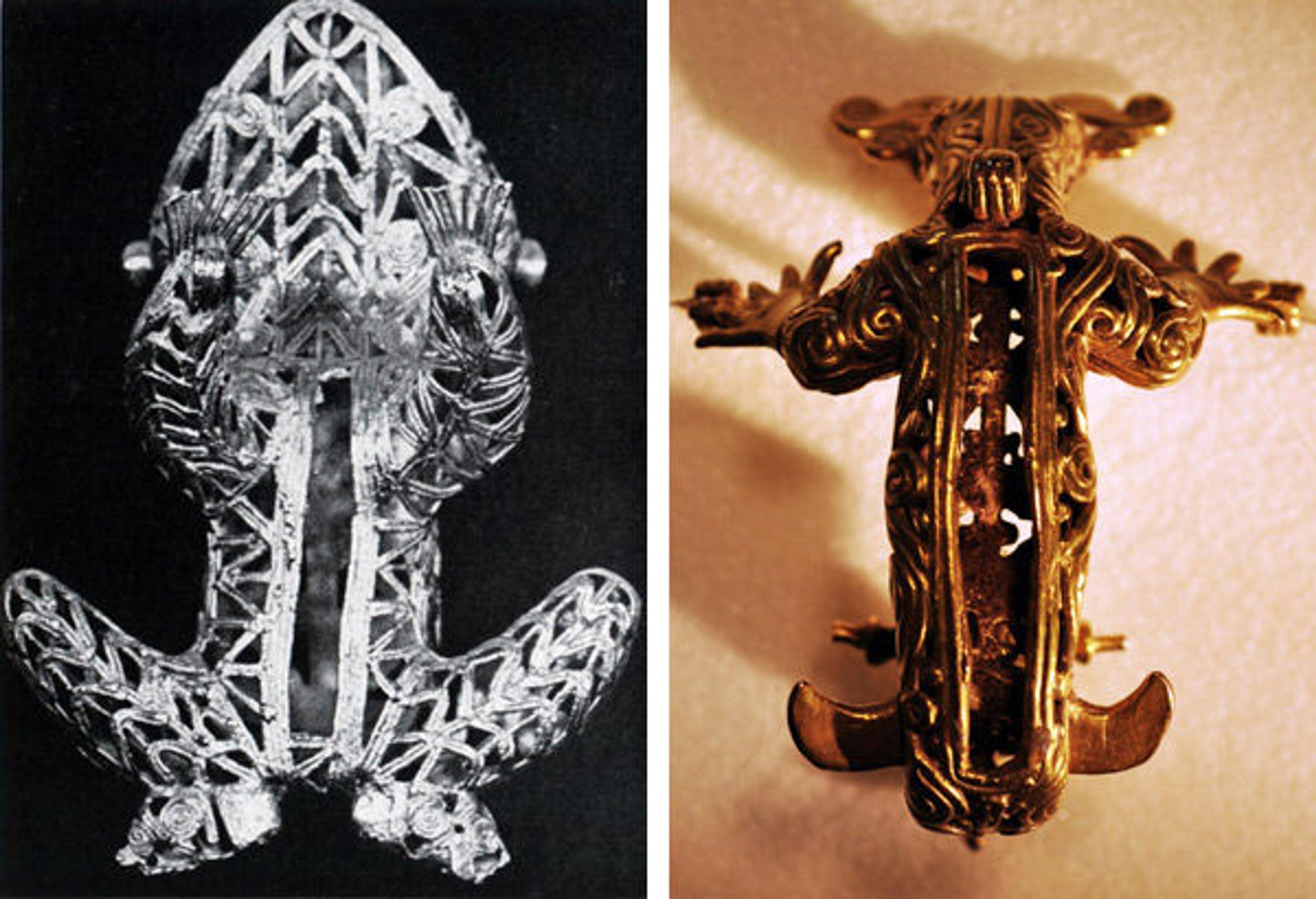

The technique of Venado Beach open-work is one of the most sophisticated ways in which ancient American artists worked with gold. Despite its similar appearance to filigree, it is known as a "false filigree"—that is, the artist worked in wires of wax and not wires of the metal itself. The works recovered by Montgomery from the Dumbarton Oaks and the Art Institute of Chicago collections, perhaps made by the same artist or workshop, show how the wax was shaped in order to facilitate the removal of the organic core around which the goldsmith built the wax shape.

First the artist would mold a solid core out of clay and/or charcoal, around which they would shape thin tubes of wax into the form of the desired figure. Working with the tiny rolls of wax at this stage was tricky: if the wax did not fully connect to all the coils and lines, then the later step of pouring the gold would fail. The artists at Venado Beach took care to leave an open rectangle of space that exposed the core. After encasing the wax figure in more clay and organic core, they would bake the mold and drain the wax before pouring the molten gold into the void left by the wax. After breaking open the cooled gold figure, the artist could then use tools to extract what was left inside of the organic core through the rectangular shape on the reverse of each pendant.

Left: Fig. 6a. Filigree pendant in the form of a frog or toad (underside), A.D. 500/1000. Cast gold; L. 18.26 cm (7 3/16 in.). The Art Institute Chicago, Wirt D. Walker Fund (1969.792); from Lothrop 1956, fig. 7. Right: Fig. 6b. Combined-figure pendant (underside), 700–1000 CE. Coclé, Panama. Gold; H 6.15 x W 5.18 x D 4.13 cm (2 7/16 x 2 1/16 x 1 5/8 in.). Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection, Washington, D.C., Pre-Columbian Collection (PC.B.372)

The Department of Pre-Columbian Studies at Dumbarton Oaks has begun a major catalogue project of their collection that will integrate all the existing studies of metallurgy, including the unpublished results of the Venado Beach excavations. Venado Beach is a very important site for understanding the development of complex polities in the culture known as Coclé, perhaps best known for the major cemeteries of Sitio Conte and El Caño. Recent excavations at sites like nearby Cerro Juan Díaz have also contributed to deepening an understanding of these important rulers, who left few traces on the surface in the form of monumental buildings. The current project at El Caño is also leading the way with its international collaboration on excavation and conservation of Coclé art used and worn by the ancient rulers of Panama.

Additional Reading

Cooke, Richard, and Luis Alberto Sánchez Herrera. "Coetaneidad de metalurgia, artesanías de concha y cerámica pintada en cerro Juan Díaz, Gran Coclé, Panamá." In Boletín Museo del Oro 42 (1997), 57–85.

Jones, Julie, ed. The Art of Precolumbian Gold: The Jan Mitchell Collection. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1985.

Jones, Julie, and Heidi King. "Gold of the Americas." The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin 59, no. 4 (Spring 2002).

Joyce, Rosemary A., ed. Revealing Ancestral Central America. Washington, D.C.: The Smithsonian Latino Center and the National Museum of the American Indian, 2013.

Lothrop. Samuel K. "Jewelry from the Panama Canal Zone." In Archaeology 9, no. 1 (March 1956), 34–40.

———. "Suicide, Sacrifice and Mutilations in Burials at Venado Beach, Panama." In American Antiquity 19, no. 3 (January 1954), 226–34.

Quilter, Jeffrey, and John W. Hoopes, eds. Gold and Power in Ancient Costa Rica, Panama, and Colombia. Washington, D.C.: Dumbarton Oaks, 2003.

Wardwell, Allen. "Some New Acquisitions of Pre-Hispanic Gold." In Bulletin of the Art Institute of Chicago 67, no. 1 (January–February 1973), 16–20.