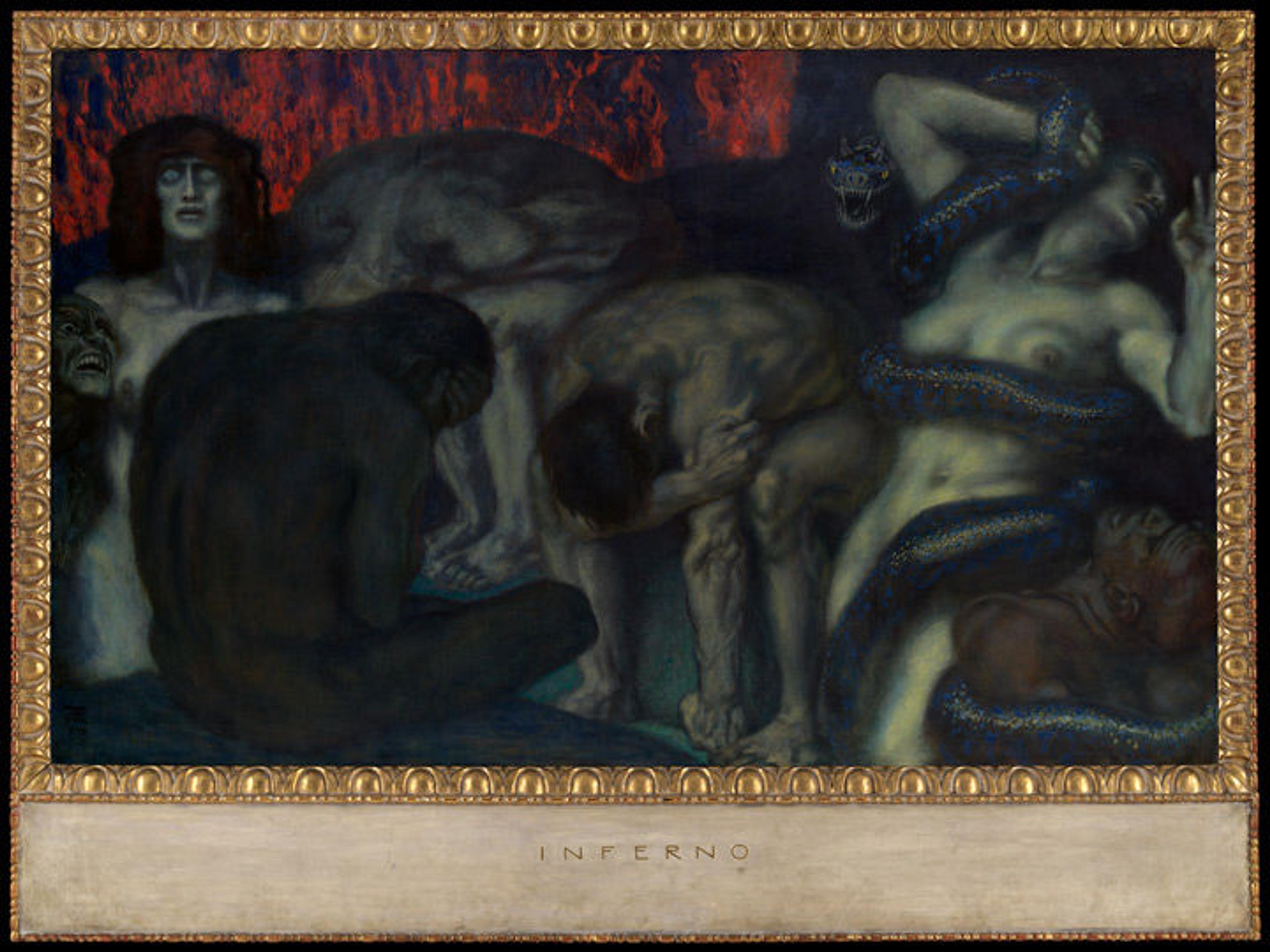

Franz von Stuck (German, 1863–1928). Inferno, 1908. Oil on canvas, 50 3/4 x 82 1/2 in. (128.9 x 209.6 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, Bequest of Julia W. Emmons, by exchange; Walter and Leonore Annenberg Acquisitions Endowment Fund; Charles Hack and the Hearn Family Trust and Mugrabi Family Gifts; Louis V. Bell, Harris Brisbane Dick, Fletcher, and Rogers Funds and Joseph Pulitzer Bequest; Pfeiffer Fund; Theodocia and Joseph Arkus and several members of The Chairman's Council Gifts, 2017 (2017.250)

«There is art that is meant to soothe and elicit gentle contemplation, and then there is art that is meant to confront. Franz von Stuck's Inferno clearly falls into the latter category. On view in gallery 800 among The Met's rich holdings of work by Auguste Rodin and his contemporaries, Inferno stops you dead in your tracks and never lets go. A scene inspired by Dante's Inferno—which also served as the point of reference for Rodin's figures from his incomplete The Gates of Hell installed nearby—Stuck's painting is a Symbolist nightmare of existential dread.»

Across the massive picture are six human figures trapped in a barren, fiery landscape. Some are tormented by a grinning demon at left and a serpent at right whose enormity and shimmery skin call to mind the hellish visions of Hieronymus Bosch and the lavish textural designs of Gustav Klimt. Each figure wrestles uniquely with eternal damnation—from the wide-eyed terror of the female figure at left, to the oppressed, curved spines of the central figures, and the almost sexual frenzy of the man and woman caught in the serpent's constrictions, which some scholars consider a reference to the original sin of Adam and Eve and eternal damnation. The compressed space of the picture and the dissonant palette of complementary colors set your teeth on edge. This is a modernist work of operatic proportions that is meant to be felt, rather than simply admired. (A similarly expressionistic statement of murder and sensual torment, Richard Strauss's opera Salome, premiered in Vienna just three years before Stuck executed the painting.)

Although a recent addition to The Met collection, the current hanging of Inferno is actually not the picture's first appearance at the Museum. The work was part of a seven-week exhibition of contemporary German art in 1909 that later traveled to the Copley Society in Boston and the Art Institute of Chicago. In addition to Inferno, four other paintings and three bronzes by Stuck were included in the exhibition, which was mounted at the pinnacle of his career. Inferno proved to be one of the most debated works in the exhibition: the New York Sun was underwhelmed by Stuck's "melodramatic, false, futile" paintings, while the New York Times trumpeted the "unique splendor" of the painting (then titled Infernal Regions) and described it as an "appalling composition of sovereign brutality . . . powerful after the fashion of the English [artist William] Blake." Despite individual tastes spanning the spectrum of acceptance, critics were overwhelmingly in awe of Inferno's confrontational nature and acknowledged its memorable power.

Installation photo of Exhibition of Contemporary German Art at The Met, 1909

One of the most important painters in turn-of-the-century Germany and a cofounder of the Munich Secession, Stuck was well known for his daring exploration of the spiritual and psychological in his work, in which he probed the extremes of virtue and hedonism, morality and sexuality. Although best known today as a painter, Stuck's large output also included work as an illustrator, furniture designer, and sculptor. (Two of his sculptures, Mounted Amazon and Wounded Centaur, are also in The Met collection, though not on view.) Stuck exhibited some of his most controversial works in the United States prior to 1909 in an effort to gain international acclaim, and The Met's exhibition bolstered the artist's reputation for giving bold expression to the dark side of the psyche.

Leveraging his training as a decorative artist and his work in furniture design—for which he won a gold medal at the 1900 Exposition Universelle in Paris—Stuck designed accompanying frames for many of his pictures, including Inferno. The picture was exhibited at The Met in 1909 in a different frame, but by 1914 Stuck had remounted the work in one of his own making. The gilded edges and stone-colored painted predella of the new frame amplify the deep colors and physical presence of the painting itself.

Inferno, in its current frame, is located to the right of Stuck's head. Atelier Friedrich Müller/Theodor Hilsdorf. Franz von Stuck with His Dog, 1914. Photograph, 17.9 x 23.5 cm. Reproduced in Ulrich Pohlmann et al., Franz von Stuck und die Photographie: Inszenierung und Dokumentation (Munich: Prestel Verlag, 1996).

Unfortunately for Stuck, German art fell out of favor in the US very soon after the 1909 exhibition and remained unfashionable for decades, following Germany's provocation of two catastrophic world wars. American collectors and institutions focused their attention on 19th-century French art—most notably the Impressionists and Postimpressionists—which came to be seen as the epitome of groundbreaking art. It is only in recent decades that the pendulum began swinging back in the opposite direction, and US museums are again pursuing German work of the period.

Through a number of recent acquisitions, including Ferdinand Hodler's The Dream of the Shepherd (Der Traum des Hirten) and Vilhelm Hammershøi's Moonlight, Strandgade 30, the Department of European Paintings is active in its campaign to expand and deepen the narrative of central and northern European art from this period in its collection. The presence of Stuck's Inferno in the galleries for 19th-century painting marks a large step forward in this process. In a way, Inferno has found an ideal home at The Met among Rodin's expressionistically modern sculptures and the dark gray walls of gallery 800—more than 100 years after its first appearance at the Museum.

Stuck's Inferno on view in gallery 800