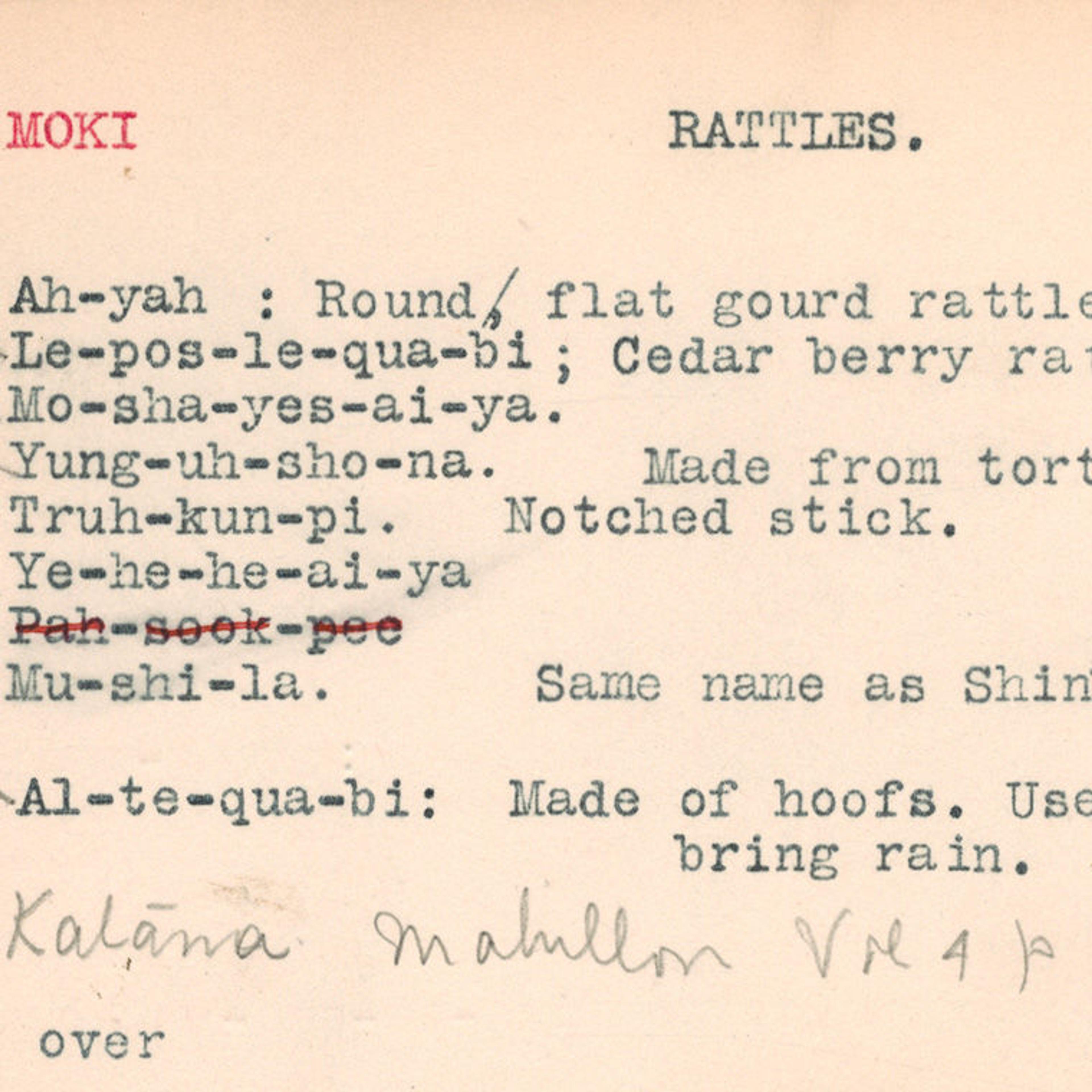

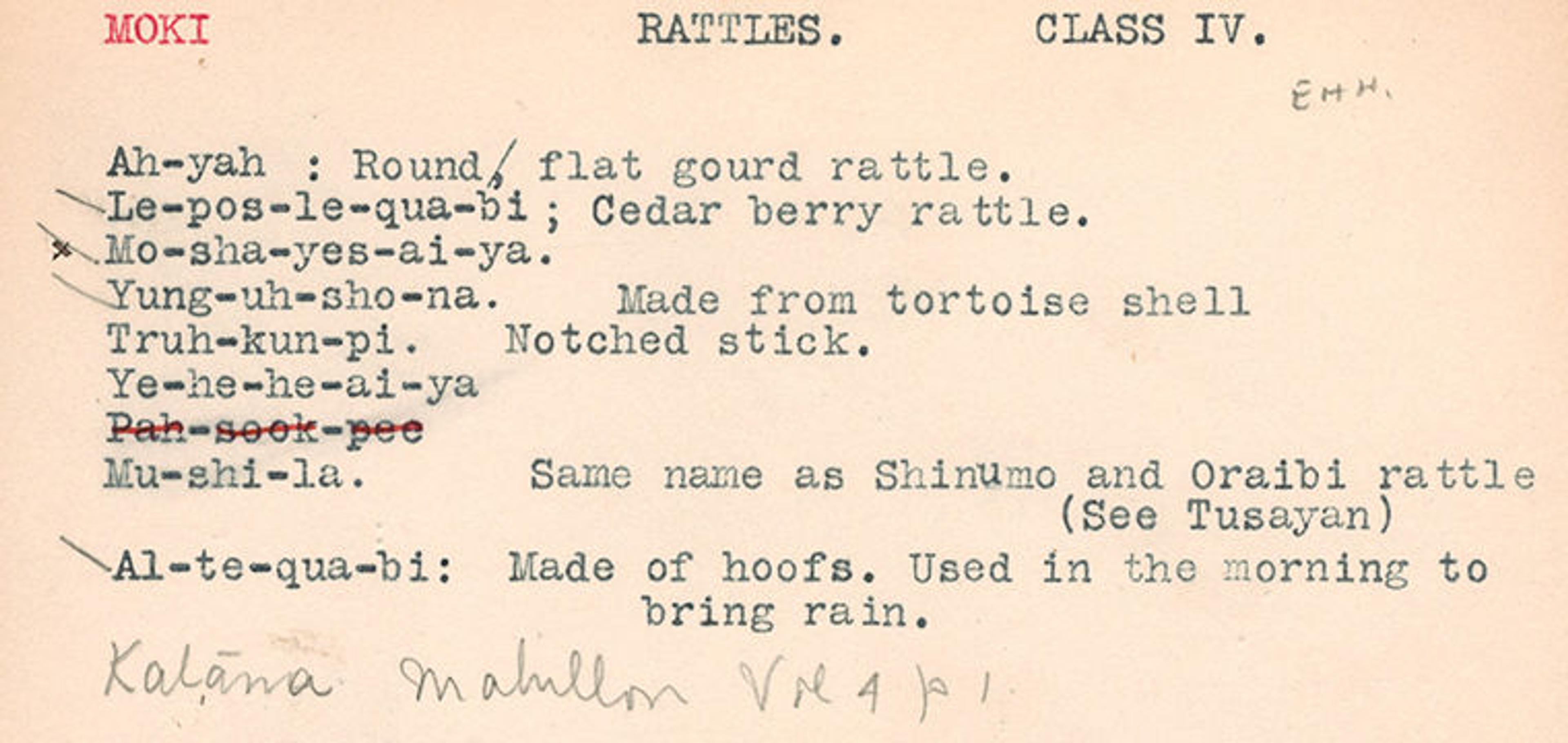

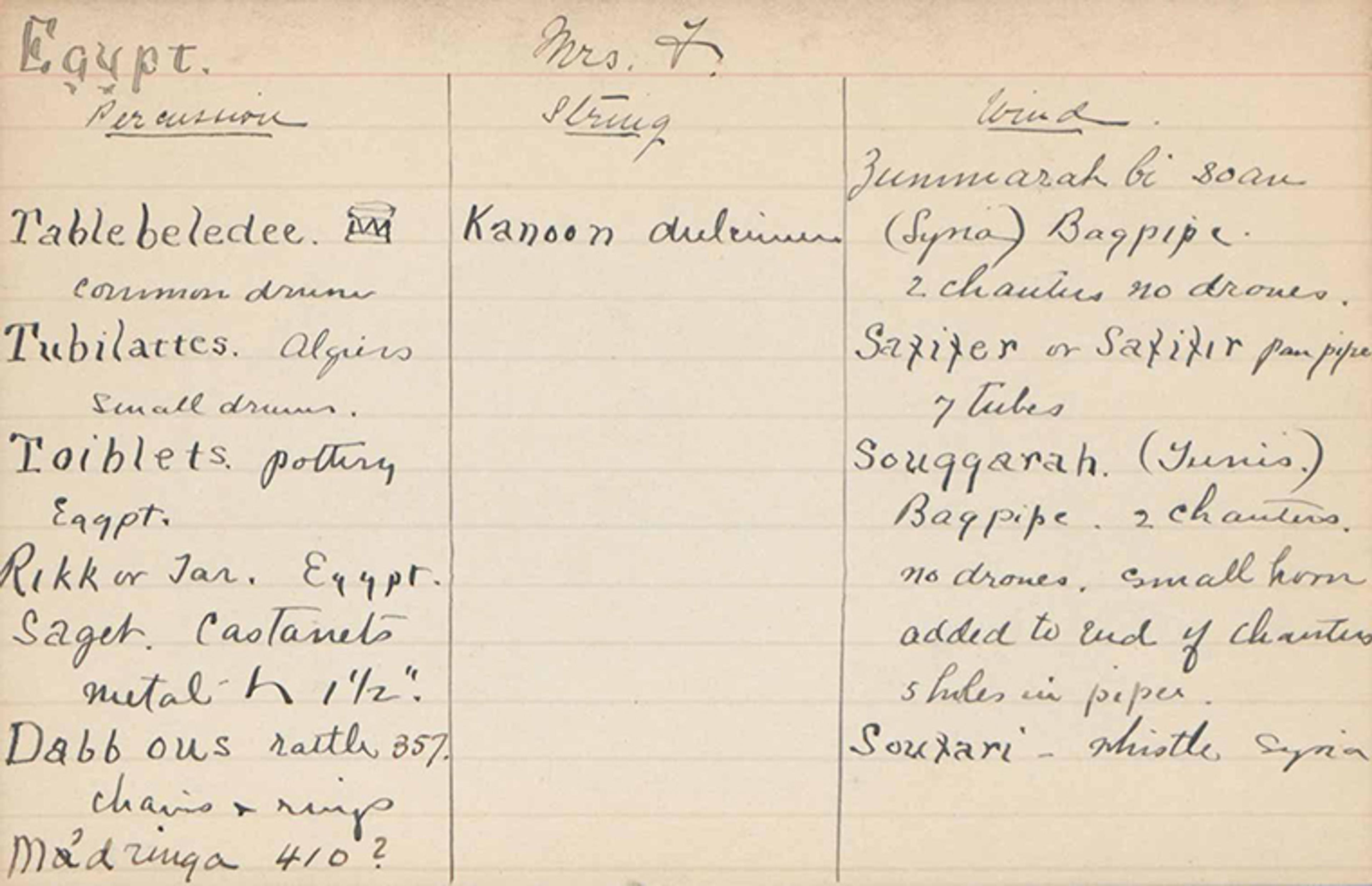

A card describing rattles in the collection of the Department of Musical Instruments at The Met. The first curator in charge of the department, Frances Morris, was an expert on American Indian instruments. Her chief mentor in the field was Edwin H. Hawley, a curator at the Smithsonian Institution, whose initials she wrote on the top right of this card.

A pre-digital information trove recently discovered in the Department of Musical Instruments archives will soon be online for researchers through the Thomas J. Watson Library.

In a (very) old box labeled "Chordophones," members of the department found a meticulous card file compiled and maintained by the first curator in charge of musical instruments—and the first woman professionally employed at The Met—Frances Morris, a Museum employee from 1896 to 1929. The more than one thousand cards are a window into how Morris researched, thought about, and organized the musical instrument displays and catalogues over the course of more than thirty years.

John Crosby Brown, treasurer of The Met, and his wife, Mary Elizabeth Brown—who together collected and donated over three thousand musical instruments to the Museum—recommended to Museum Director Luigi Cesnola that Morris be hired; they also subsidized her paycheck for several years. Mary Elizabeth was active until about 1903 in helping the Museum classify the Brown donations; some information in Morris's card file is from correspondence between Mary Elizabeth and the original sellers or donors of instruments that were transferred to the Museum.

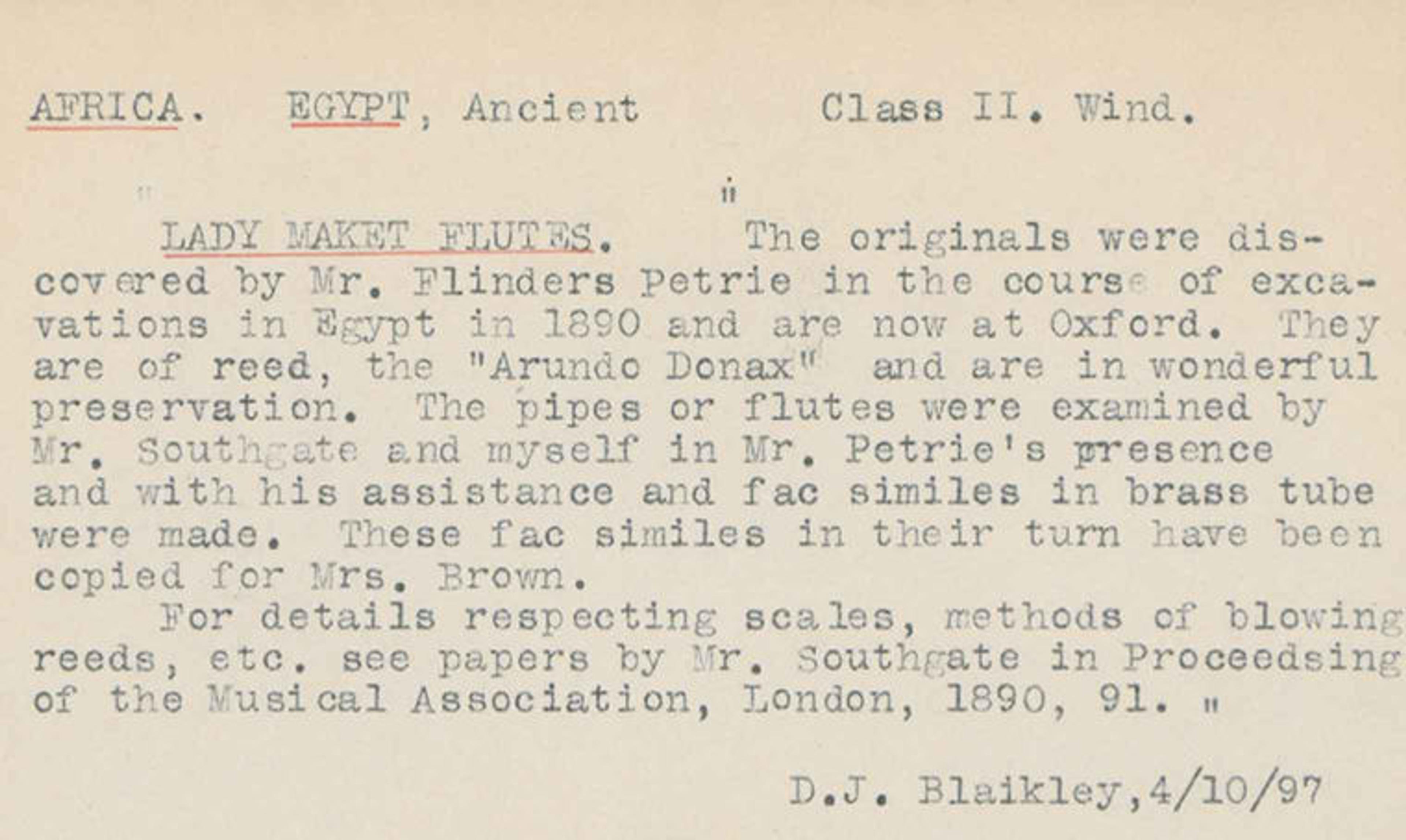

Museum donor Mary Elizabeth Brown commissioned copies of instruments when she could not locate originals for The Met collection. This card describes reproductions of Ancient Egyptian flutes she had made at Oxford University under the supervision of the archaeologist Flinders Petrie.

The cards are filed primarily by the instrument's location of origin—in itself a significant fact, since it shows that Morris viewed the location (as opposed to the type of instrument or date) as the most important way of classifying these objects. Her location titles varied: sometimes a country such as Korea was recorded; at other times, a region ("Arabia") was noted. She attempted to be comprehensive. There is a divider labeled Iceland, but the only card in the tab states crisply: "There is no use for any instrument on this island." As was typical in the Victorian era, Morris did not shy away from value judgments. She copied onto a card the pronouncement of an Athenian collector, M. K. Kalopothakes:

The Greeks of today cannot be said to have great talent for music, but they enjoy it and indulge in it very much. Men delight in going round the streets, two or three together, with their arms interlaced, singing the ballads of the country in a monotonous way. In summer they do this till very late at night.

Morris compiled dozens of cards to serve as a bibliography. The one labeled "Bibliography—Street Pianos" lists an issue of the Scientific American magazine from 1894 that includes technical drawings of the instrument, details of use and manufacture, prices, and the information that "they are used principally by Italians who push them around the streets in two-wheeled carts." In many cases the source for bibliographical entries is shown as New York's Lenox Library. There are bibliography cards for types of instruments (such as stringed) and for places (such as Poland) and meticulous volume and page citations for periodicals like Harper's. There are even cards for music-related items, including the plaster casts of sculptures so beloved of nineteenth-century museums, which were held elsewhere in The Met. Indeed, an entire section of the card file is headed "Music—illustrated by art objects in the Museum." Cards in this section are sorted under early Museum highlights, including "Gold Room," "Cypriote art," "Egyptian antiquities," "Porcelain" and "Jade," as well as "Paintings" and "Statuary."

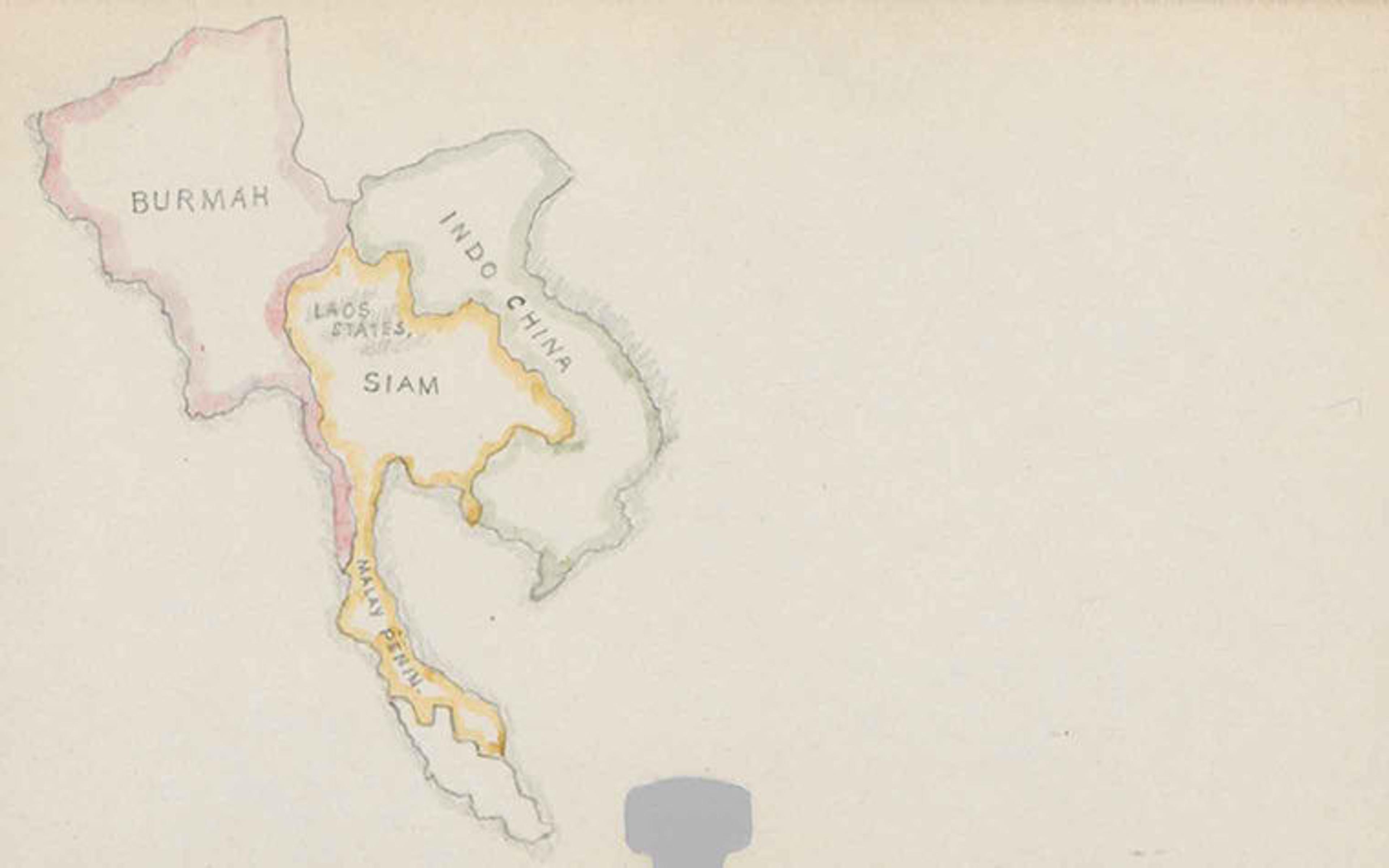

Morris's map of three Southeast Asian countries from which The Met collected instruments

In some cases, an individual card was prepared with exactly the description from The Met's catalogue. One description of an instrument donated in 1885 by Met trustee Joseph Drexel first appeared in the Asia catalogue prepared by Morris in 1901. The card also lists the gallery and case numbers where the instrument was displayed. By the gallery numbering, which changed in 1914, we can be certain that the card was prepared after that year.

Many cards have penciled-in catalogue numbers and can therefore be tied with certainty to accession numbers (which, for objects acquired before 1914 by the department, are based on catalogue numbers). These cards sometimes also list the person who acquired the instrument—a missionary in Burma, or a diplomat in South America, say. They provide contemporary names for the instrument, and may have quotations from letters written about the circumstances of the acquisition or the use of the instrument by the people who made it. There may be cross-references to other instruments acquired from the same source or at the same time.

This information will soon be linked to the object descriptions that are available publicly on the Museum's online collection. It is immensely valuable information. With musical instruments in particular, The Met received donations in large groups, without photos or detailed descriptions. Today, we may not know which of many dozen drums or violinsnow in the collection was included in a group of donations given in 1893, say. These cards fill in some such gaps. Card 761, for example, relates to the instrument accessioned as 89.4.3134. This card and several others reflect now-outmoded, Western-centric, nineteenth-century ways of thinking. Although they meticulously document important data about the use, manufacture, and origins of objects, these cards also indisputably imply that the less a culture resembled European norms, the less civilized it was. This particular card provides the information, from Miss Josephine Hauser of 128 East 54th Street, that the instrument is "used by a tribe of semi-civilized cannibals called Battocks who are similar to the wild men of Borneo. They live in the Atjeh mountains on the North Coast of Sumatra, which belongs to Holland."

Morris's correspondence with other experts is evident in cards such as this one. At the top, she mentions "Mrs. F," whose full name was Sarah Sagehorn Frishmuth, an expert on Asian instruments.

Other cards in the file are sources Morris relied on for historical information. The collector Sarah Sagehorn Frishmuth, a major donor and honorary curator at what is now the Philadelphia Museum of Art, was a frequent correspondent of Morris's and the source of much information on classifying Chinese and Korean instruments. Another card lists the writer Rudyard Kipling as the source for information on a Burmese temple bell; yet others quote the Hudson River School painter Frederic Edwin Church, who collected several instruments now at The Met.

Still other cards have meticulous maps, or scaled hand drawings of instruments Morris deemed particularly important. Some describe objects that the Museum ultimately did not acquire. The then-contemporary desire for encyclopedic completeness is reflected in a number of cards describing copies Morris obtained of instruments from other collections when she could not locate an original instrument for the Museum.

Sometimes a series of many cards laboriously transcribes a relevant passage from a published work, the catalogue of another institution, or the response from a scholar at another museum or in another country to a question from Morris.

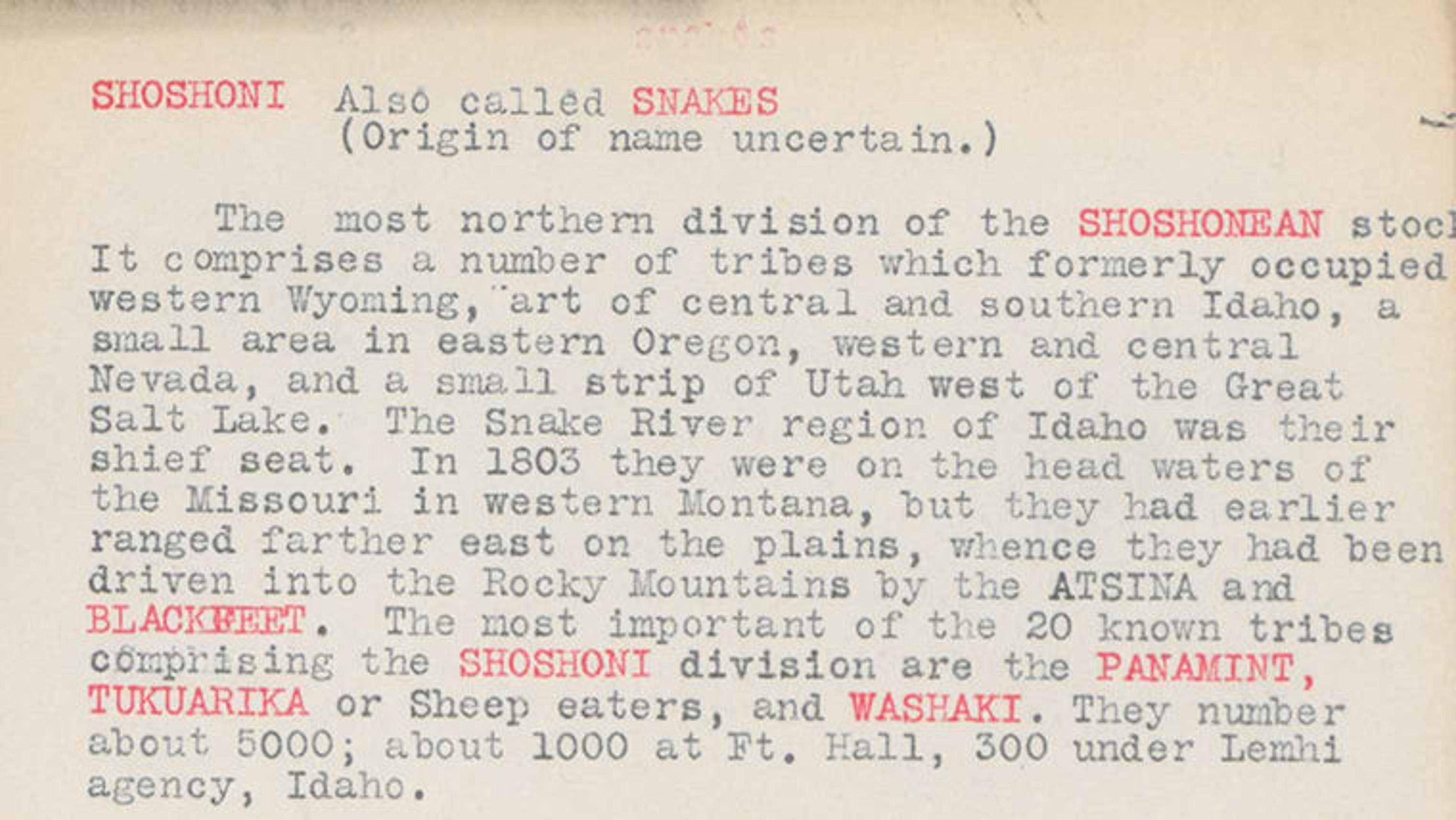

Morris had a special interest in American Indian instruments. This card describes objects made by groups that once occupied western Wyoming.

Probably the most important section of the card file is the American Indian section; almost half of the cards relate to this area. At the time The Met acquired many of its instruments, there were other large and well-catalogued collections of European instruments, but The Met collection was unique in its American Indian strength. Morris, who was largely self-taught in this area, spent almost two decades researching tribes and languages and devising a system for organizing and classifying the Museum's American Indian instruments before publishing her magisterial 1914 catalogue of the Museum's instruments, Oceania and America. In her endeavors, Morris benefited from the endless assistance of Edwin H. Hawley, curator from 1885 to 1918 of the Smithsonian's collection of American Indian instruments (the only other significant one in the country), as shown by the initials "EHH" on many of the Morris cards for Moki (now called Hopi) rattles. In the course of her work at The Met, Morris was ultimately recognized as an international expert in this area.

The serendipitous discovery of this fine index has provided the Museum not only with long-lost, valuable details about objects in its collection; it also opens a window into the curatorial practices, research, and musicological scholarship of more than a century ago.