Each month, The Met is sharing videos, essays, and other media that speak to a specific theme relevant to our present times. This month, we bring you a selection of artworks that have survived, been altered by, or were created under extraordinary circumstances. These include artifacts that have survived war and iconoclasm, as well as dramatic depictions of the struggles for abolition, suffrage, and equality. Jennifer Farrell, an associate curator in The Met's Department of Drawings and Prints, opens with the story of how Henri Matisse turned to a new technique in the middle of World War II.

Henri Matisse (French, 1869–1954). Circus (Le Cirque), plate II from the illustrated book "Jazz," 1947. Pochoir, 6 5/8 x 25 5/8 in. (42.2 x 65.1 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Lila Acheson Wallace, 1983 (1983.1009[1–22]). © 2020 Succession H. Matisse / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

"Jazz," Henri Matisse's radical rethinking of what an illustrated book could be, depicts scenes of the circus, travels, mythology, and fairy tales. Yet despite the rhythmic juxtapositions of forms, the undulating lines, and the ostensibly joyous subjects, "Jazz" is haunted by a deep sense of danger, loss, dread, and even death.

Matisse began the project during World War II after France had fallen to the Nazis. Citizens were being separated from their families, arrested, and killed, and the country experienced severe deprivations of basic necessities. Several members of Matisse's family were active in the Resistance, and some were captured, imprisoned, and tortured. Matisse, who had stayed in France, became gravely ill in 1941 and nearly died. Surgery saved his life but left him weak and with restricted mobility. It was during this period that he began to focus on a technique he called "drawing with scissors." In 1943, he started the cut-outs for "Jazz" using colors that he later described as "vivid and violent." The prints in The Met collection, made through a technique called pochoir, retain Matisse's intense colors.

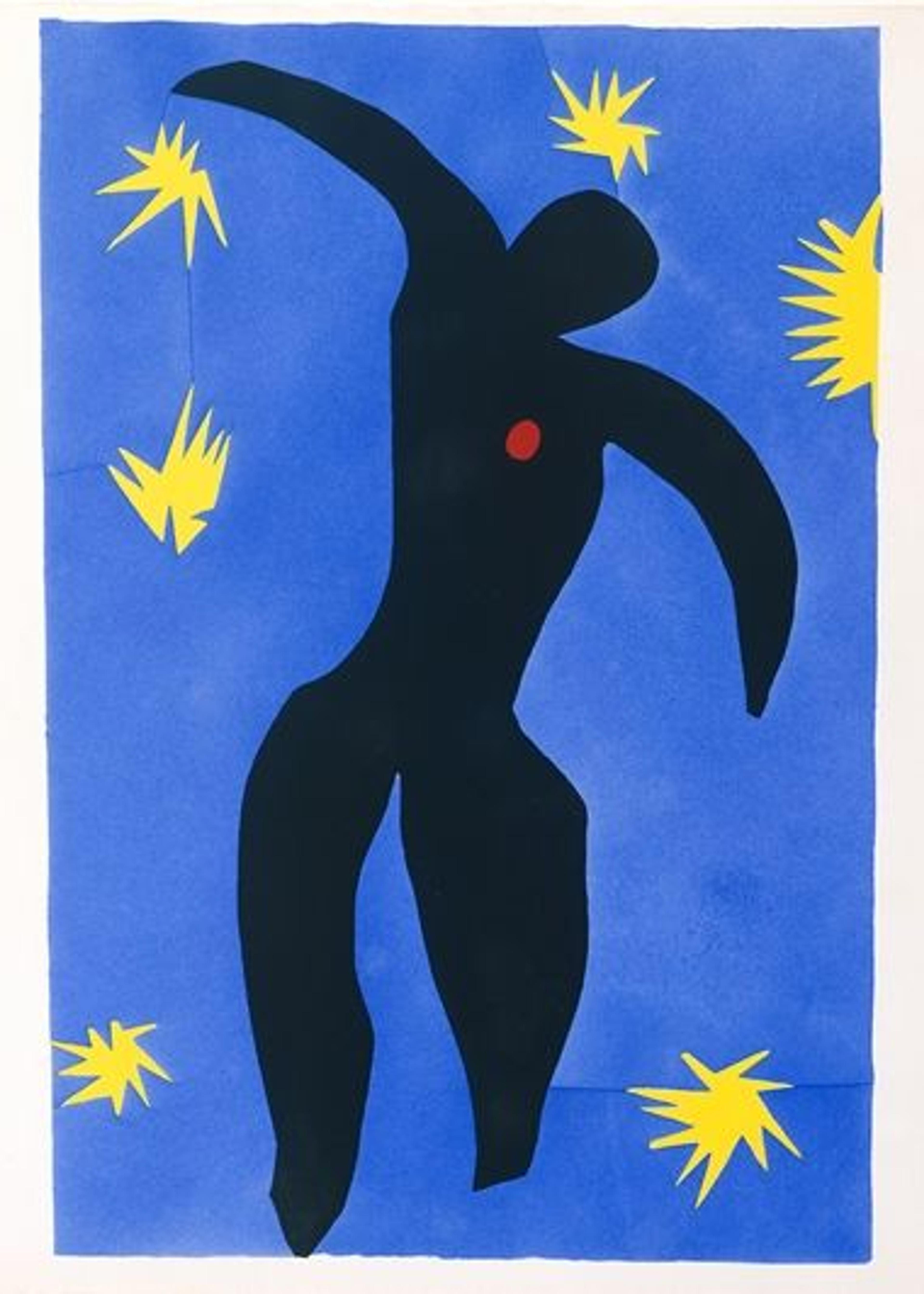

Right: Henri Matisse (French, 1869–1954). Icarus, plate VIII from the illustrated book "Jazz," 1947. Pochoir, 16 1/2 x 10 1/4 in. (41.9 x 26 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Lila Acheson Wallace, 1983 (1983.1009[8]). © 2020 Succession H. Matisse / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

With "Jazz," Matisse created a powerful and poetic work that concurrently engages multiple, often contradictory themes. Icarus recalls a trapeze artist in a circus, the Greek myth, and a figure who has been killed by a gunshot or bomb. That image and several others may also refer to the risks of artistic creation, especially as a form of cultural resistance. The Cowboy; The Horse, Rider, and Clown; and The Nightmare of the White Elephant convey a sense of confinement, captivity, anguish, and brutality through the undulating whips and lassos, and the red forms that pierce the elephant balancing precariously on a small ball. In multiple prints, figures appear as if they are moving through space, perhaps even in a fatal fall. There are also references to contemporary figures, such as General Charles de Gaulle in Monsieur Loyal and the Gestapo in The Wolf.

"Jazz"both responded to and reflected on the extraordinary, horrific circumstances Matisse endured of war, illness, and separation from his family. At the same time, its visually stunning, boldly colored images recalled memories of different times and places that could perhaps offer a moment of reflection and even joy.

Conversations on the Destruction of Cultural Heritage in Iraq and Syria

Often, an unexpected casualty of war is art. In this video, three archaeologists discuss the destruction of cultural heritage during recent conflicts in Iraq and Syria. Produced for the 2019 exhibition The World between Empires: Art and Identity in the Ancient Middle East, this nuanced conversation touches on the impact of such loss, the symbiotic relationship between human and cultural targets, and the potential responses.

"It seems misguided to focus on monuments … when the population is at risk," says Columbia professor Zainab Bahrani. "However, I would say that people and their monuments and their works of art are entangled in this region. And to wipe out or destroy the heritage, the landscape, the monuments, is a way of destroying people."

Rayyane Tabet / Alien Property

Alien Property, the artist Rayyane Tabet's current exhibition at The Met, tells story of spycraft between two world wars. In 1929, Tabet's great-grandfather was tasked by the French government in Lebanon to spy on German archaeologist Max von Oppenheim, who had discovered a Neo-Hittite palace in modern-day Syria. Baron von Oppenheim took many of the site's artifacts back to Berlin, where in 1943 they were reduced to 27,000 fragments by an Allied bomb. Four intact stone reliefs became part of The Met collection, and the others' reconstruction has been a constant project since 1990.

As in the conversation between archaeologists above, the three essays in this Bulletinbring out the personal dimension of an epic story, demonstrating the resiliency of art and the importance of preserving our cultural heritage in times of extraordinary circumstance.

Diana Al-Hadid on the Cubiculum from the Villa of P. Fannius Synistor at Boscoreale

This cubiculum (or bedroom) was salvaged from an ancient Roman villa at Boscareale, near Pompeii, a location contemporary artist Diana Al-Hadid calls "the ancient Hamptons": a retreat for the upper classes. "You really see the opulence," Al-Hadid says in this episode of The Artist Project. When the villa was built sometime between 50 and 40 B.C., it sat on the slopes of a volcano that had been dormant for almost three hundred years.

Here, Al-Hadid reflects on how Mount Vesuvius's eruption in A.D. 79 colors our perception of the villa today. She sees it as both an incredible example of ancient Roman architecture, as well as a record of a cataclysmic event that changed Roman life. "It's a strange paradox: this complete destruction annihilated an entire region but at the same time preserved it," she says. "The event is laminated into the image."

Why Born Enslaved!

Just as works of art might preserve the traces of a natural disaster, they can also be also ingrained with moments of massive social and political change. This episode of MetCollects features a sculpture by Jean-Baptiste Carpeaux. The abolitionist lament carved into its base can be translated to, "Why Born Enslaved!" The white marble bust, carved in 1873, depicts a Black woman, pained and struggling against the rope that binds her.

In the accompanying essay, curators Sarah Lawrence and Elyse Nelson write about the complicated ways we might view this image today. They direct our attention not only to the expressive naturalism of the carving, but to the problematic eroticism and objectification embedded in a white artist's portrayal of a Black subject. In the video above, poet Wendy S. Walters recites a poem she wrote in response to the sculpture. In it, she evokes the mind and emotions of the sculpture's model, who may have been a recently emancipated slave:

The woman I've been mistaken for

Is not myself, and yet I've developed

An expression of agony to share

Despite being so long lonely.

How did this model experience her extraordinary circumstance of being both newly freed as well as an eternal symbol of enslavement?

The Mother of Us All

One of the last works that Gertrude Stein wrote before she passed away in 1947 was a libretto chronicling the life of Susan B. Anthony, an abolitionist and leader of the women's suffrage movement. This year, The Met staged Stein's dramatic opera (scored by Virgil Thomson) to celebrate Anthony's two-hundredth birthday and the centennial of the nineteenth amendment, which acknowledged women's right to vote. In this recording of one night's performance, experience the dramatic re-enactment of Anthony's fight to build a movement, which inspired a years-long struggle for equality.

Anthony's extraordinary biography remains strikingly relevant centuries later. "Each time I see it, it feels like it's been ripped from the day's headlines," wrote classical music critic Zachary Woolfe in the New York Times of The Met's staging. "Even after voting rights are extended to all, we see clearly that they're hardly secure."