Isamu Noguchi (American, 1904–1988). Kouros, 1945. Marble, Height: 9 ft. 9 in. x 42 1/8 in. x 34 1/8 in., 619 lb. (297.2 x 107 x 86.7 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Fletcher Fund, 1953 (53.87a-i) © 2020 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

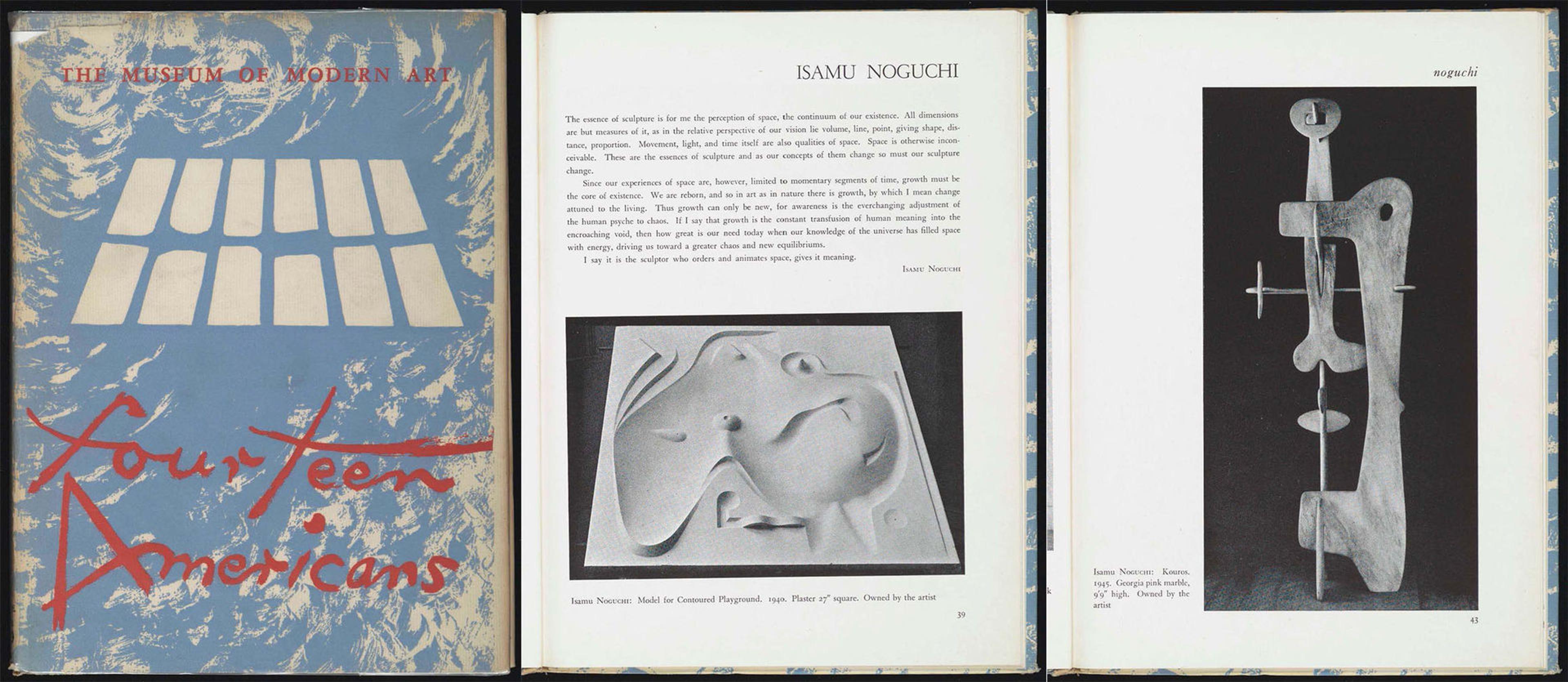

Isamu Noguchi’s Kouros is a statuesque assemblage of eight pink marble slabs joined in a delicate balance that evokes an ancient Greek figural sculpture type. During the mid-1940s, Noguchi worked with interlocking stone forms to create several ambitious works of this sort, which quickly drew the attention of museum curators and art critics. Completed in the artist’s Greenwich Village studio in 1945, Kouros soon went on view at the Museum of Modern Art as a loan from the artist to the temporary special exhibition 14 Americans. In a written statement published in the catalogue for this show, Noguchi posited a metaphysical framework for understanding his work: “growth is the constant transfusion of human meaning into the encroaching void… I say it is the sculptor who orders and animates space, gives it meaning.”

Fourteen Americans exhibition catalog, Edited by Dorothy C. Miller, with statements by the artists and others, The Museum of Modern Art, 1946.

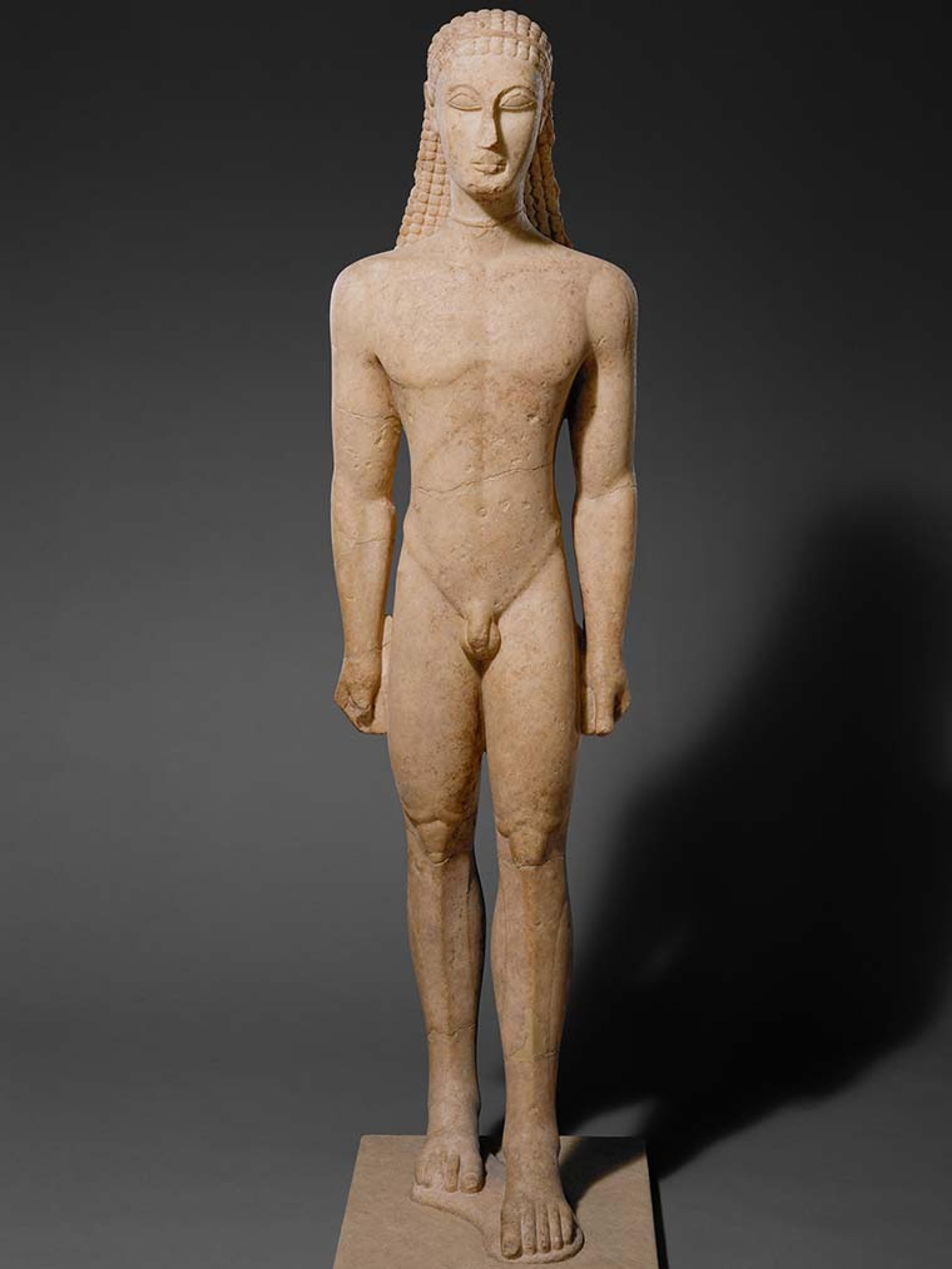

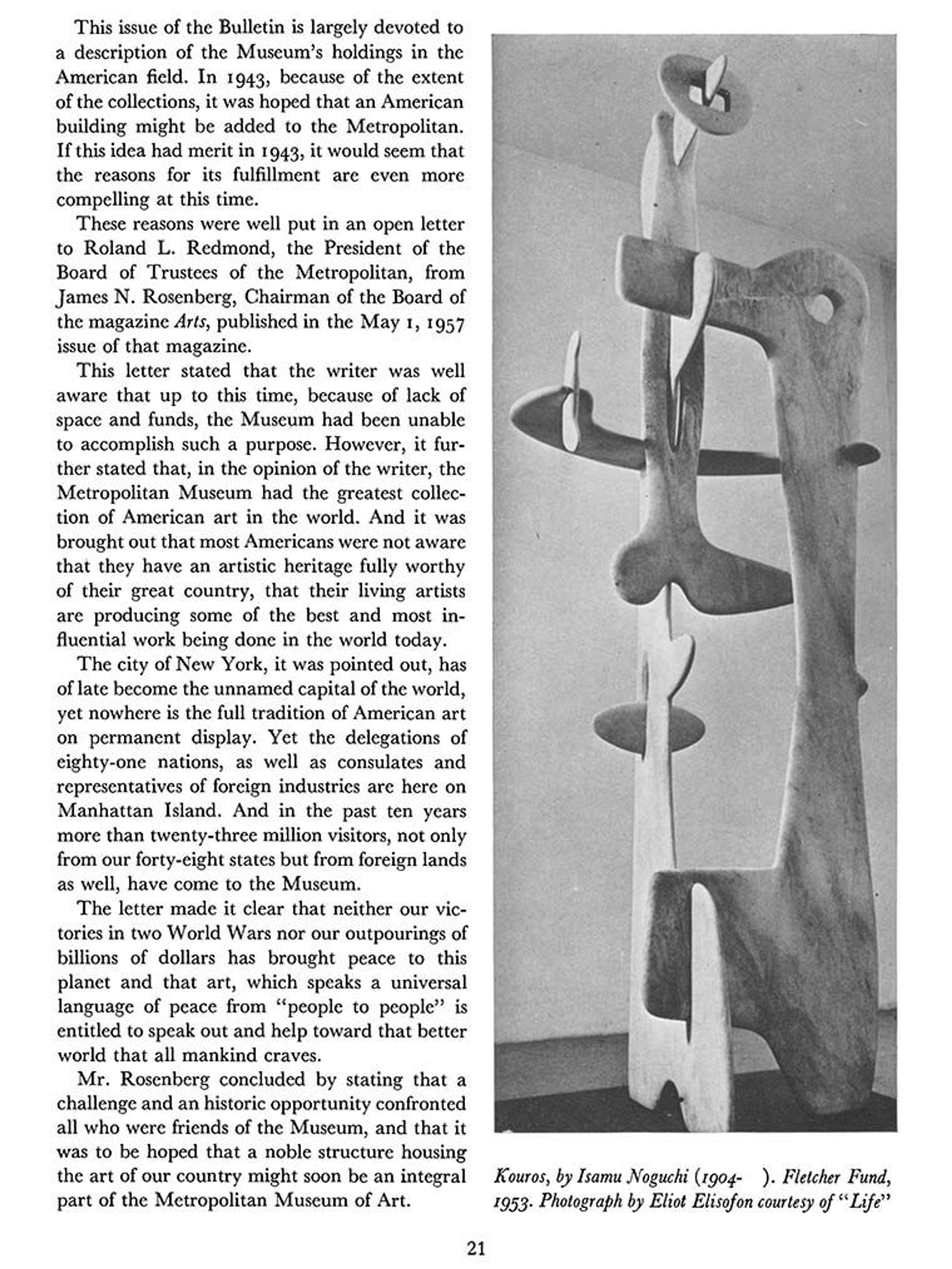

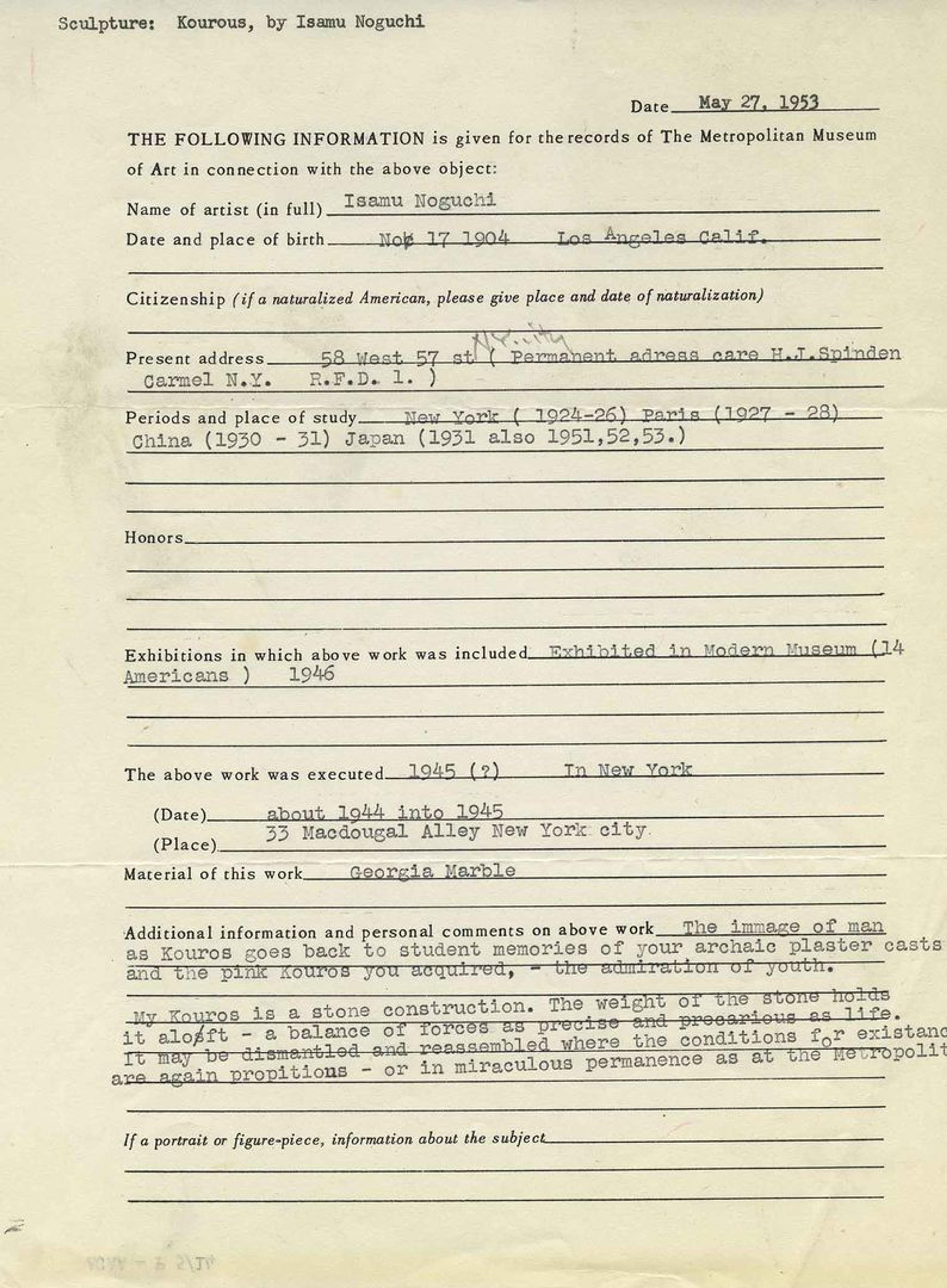

The Met bought Kouros from Noguchi in 1953 for $6,000, on the recommendation of contemporary art curator Robert Beverly Hale, who sought to deepen the Museum’s engagement with living American artists. Hale presented the acquisition with a half-page illustration accompanying his essay “The American Moderns,” an overview of his collecting strategy published in the summer 1957 Museum Bulletin. From the artist’s perspective The Met was a fitting home for this important piece, because its conception and creation was, in part, a response to a sculpture from antiquity on view in the Museum’s gallery of classical art. “The image of man as Kouros,” Noguchi wrote in response to a Met inquiry, “goes back to student memories of your ancient plaster casts and the pink kouros you acquired—the admiration of youth.” The pink object he refers to is most likely a sixth century B.C. sculpture purchased by the Museum in 1932.

Marble statue of a kouros (youth). Greek, Attic, ca. 590–580 B.C. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Fletcher Fund, 1932 (32.11.1)

Robert Beverly Hale, "The American Moderns," The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin, New Series, Vol. 16, No. 1 (Summer, 1957)

Noguchi suggested that his twentieth-century Kouros “may be dismantled and reassembled where the conditions for existence are again propitious—or in miraculous permanence as at the Metropolitan.” This recommendation is remarkable from the standpoint of winter 2020, when visitors to The Met will not find Kouros displayed in its usual “permanent” home in the modern and contemporary art galleries. Instead, it currently appears in a most “propitious” setting—the entrance gallery of the Museum’s 150th anniversary exhibition Making The Met, 1870 to 2020, in the company of superlative works of art from around the globe and representing thousands of years of human creativity. In order to present Kouros in this unique context, Met conservators in fact “dismantled and reassembled” the sculpture, as Noguchi had authorized long before.

Isamu Noguchi, Information Form, 1953, Office of the Secretary Records, The Metropolitan Museum of Art Archives.

These insights into Noguchi’s inspiration for Kouros, and his vision of its future possibilities, are known today because he wrote them down at the invitation of the Museum at the time of the object’s sale. Whenever Robert Beverly Hale acquired a contemporary artwork for The Met, it was his policy to send to its creator a one-page form that asked about the artist’s places of birth and residence, education and training, and exhibition history. This document also had ample space to share details about the newly acquired object—when and where it was made, its materials, and any other “personal comments” the artist chose to share. Such knowledge was useful to Hale and other staff as they cataloged and wrote labels for new acquisitions made by artists who, in some cases, were not already represented in the Museum collection, or about whom scant biographical information was then available. Today, dozens of these artist-completed forms are filed among artwork acquisition papers kept in the Museum Archives. They provide fascinating contextual information about many important works among The Met’s holdings of twentieth-century American art, as well as lesser known objects from the era.

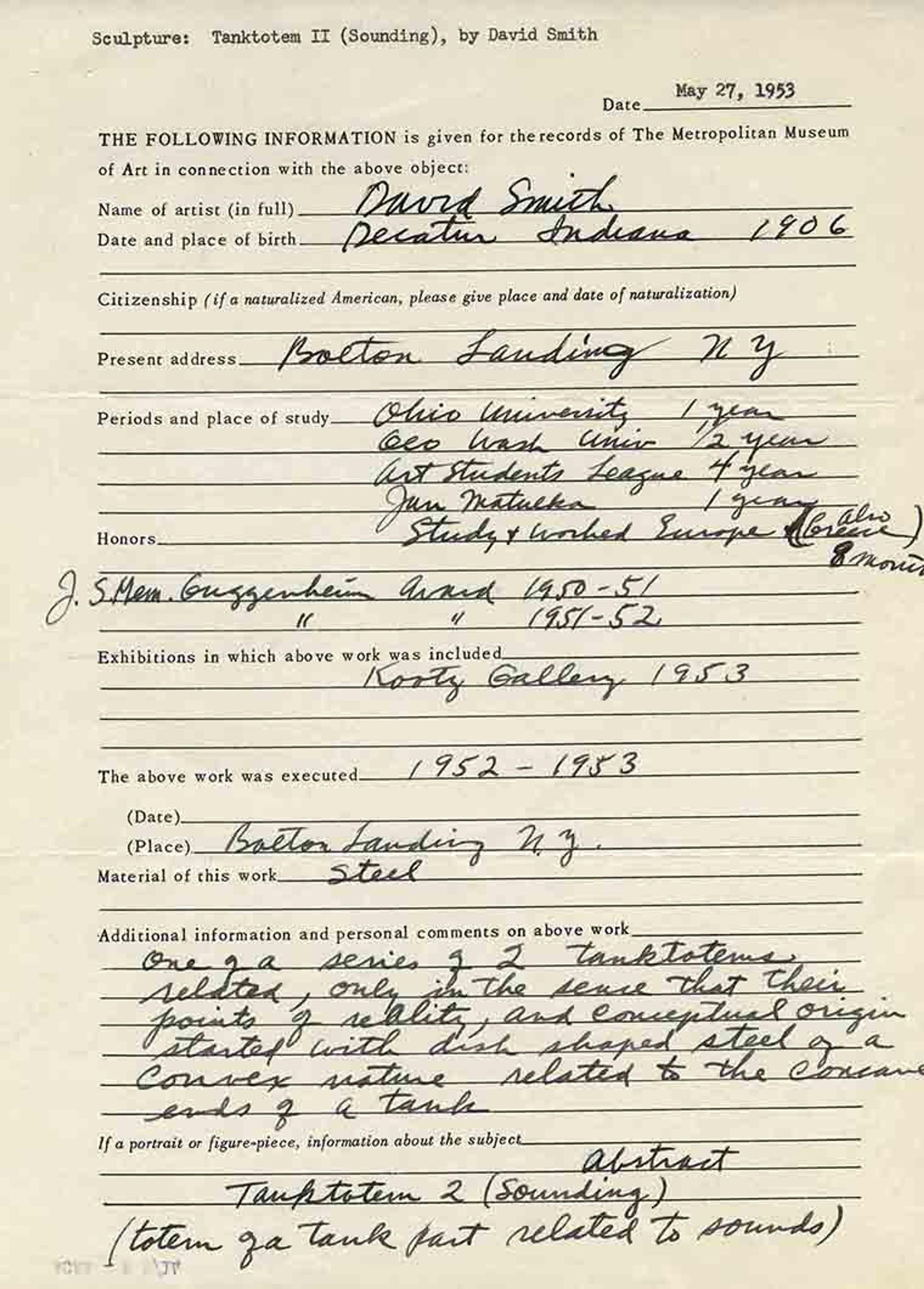

David Smith, Information Form, 1953, Office of the Secretary Records, The Metropolitan Museum of Art Archives.

David Smith (American, 1906–1965). Tanktotem II, 1952–53. Steel and bronze, 80 1/2 x 49 1/2 x 18 1/2in. (204.5 x 125.7 x 47cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Fletcher Fund, 1953 (53.93) © 2020 The Estate of David Smith / Licensed by VAGA at Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY

David Smith, like Noguchi, wrote about the genesis of his sculpture Tanktotem II, purchased by Hale for The Met around the same time as Kouros. Smith stated matter-of-factly that the “conceptual origin” of his anthropomorphic abstraction “started with dish shaped steel of a convex nature related to the concave ends of a tank.”

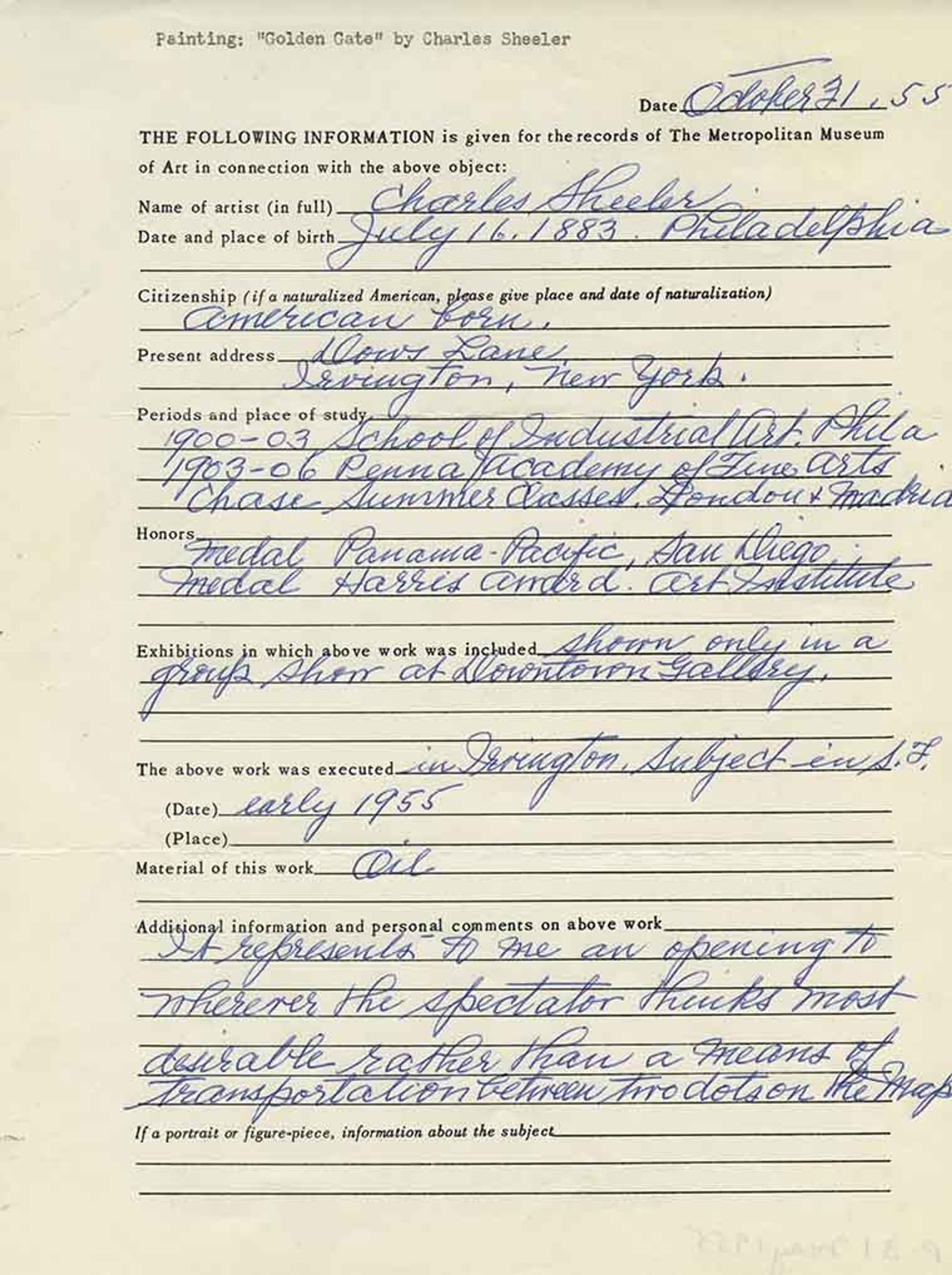

Charles Sheeler, Information Form, 1955, Office of the Secretary Records, The Metropolitan Museum of Art Archives.

Charles Sheeler (American, 1883–1965). Golden Gate, 1955. Oil on canvas, 25 1/8 × 34 in. (63.8 × 86.4 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, George A. Hearn Fund, 1955 (55.99)

Other artists used their forms to suggest how viewers might interpret their work. For example, Charles Sheeler, best known as a painter of sharp-edged industrial scenes, characterized his late masterpiece Golden Gate invitingly as “an opening to wherever the spectator thinks most desirable rather than a means of transportation between two dots on a map.” Abstract Expressionist Robert Motherwell noted wryly that the subject of his painting Ile de France referred “to the district in France, not the steamship.” That picture was one year later exchanged by the Museum for another example of Motherwell’s work, La Danse II, which the artist warned “photographs poorly because the vermillion and yellow ochre of the background are so close tonally that they merge in black + white photos.”

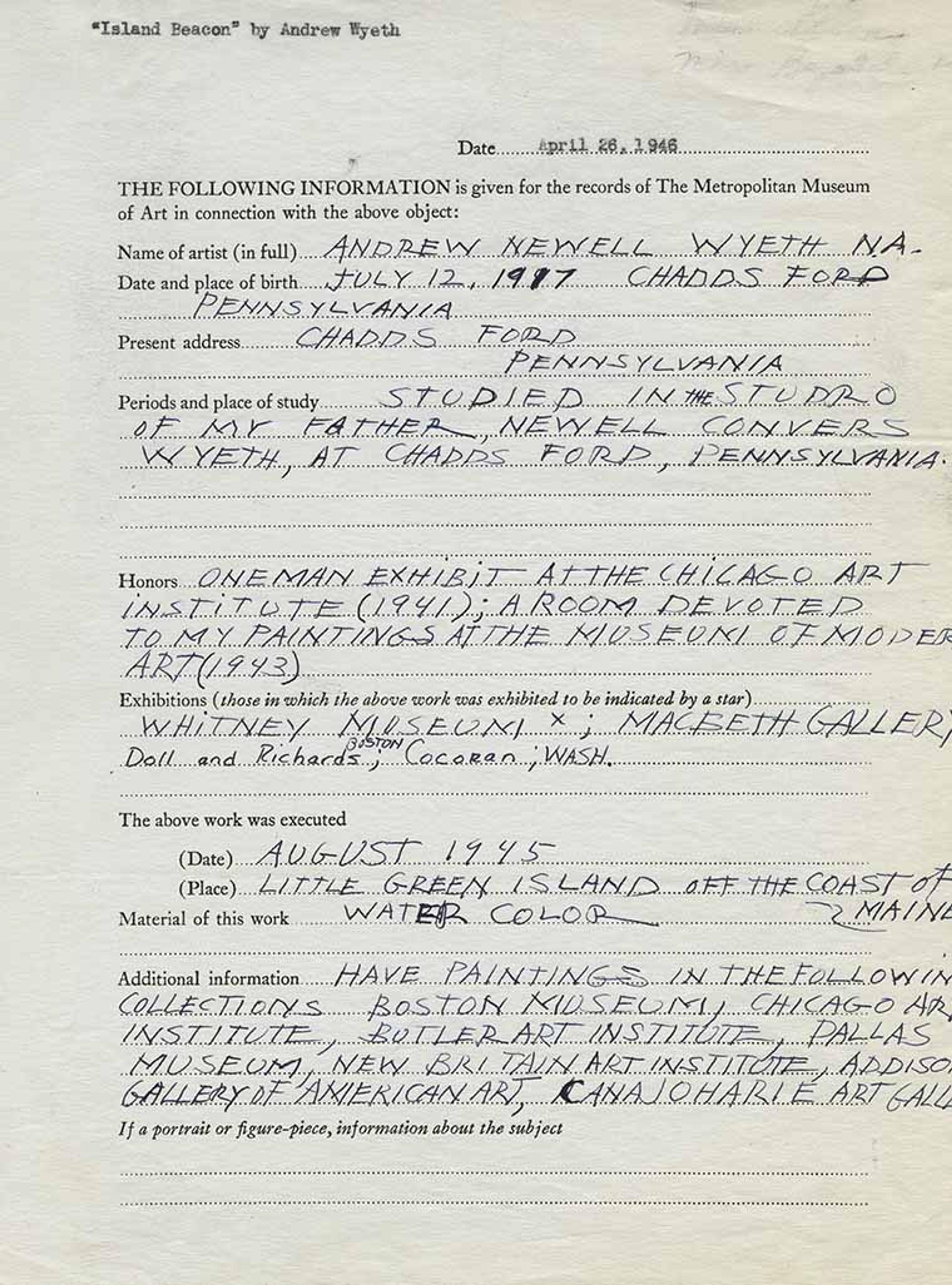

Andrew Wyeth, Information Form for Island Beacon, 1946, Office of the Secretary Records, The Metropolitan Museum of Art Archives.

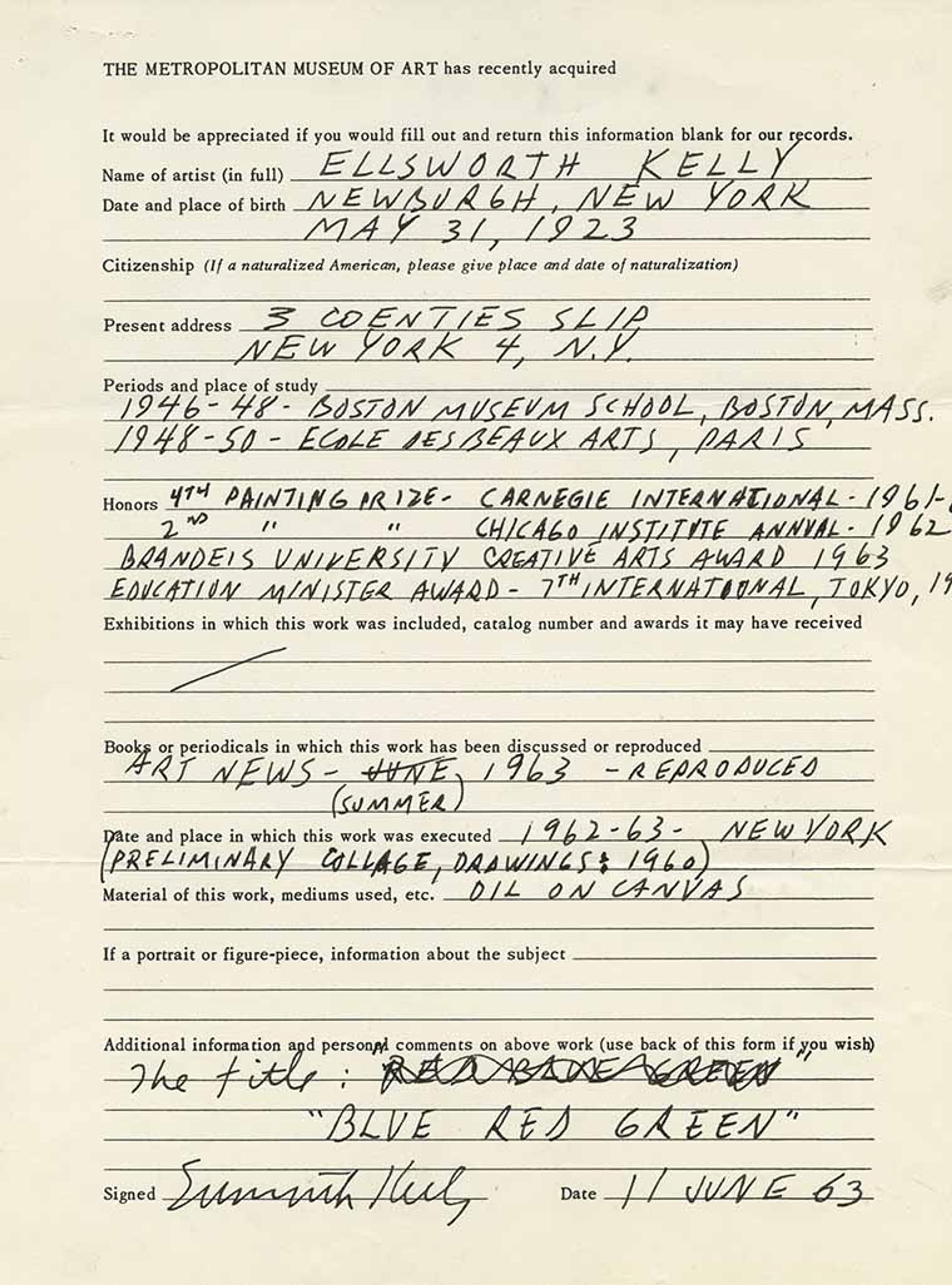

Ellsworth Kelly, Information Form for Blue Green Red, 1963, Office of the Secretary Records, The Metropolitan Museum of Art Archives.

In addition to telling us what visual artists felt and thought about their work, these forms also present us with good examples of their handwriting. On that basis alone some of these sheets invite curious comparisons. Andrew Wyeth, a realist painter famous for somber portraits and landscapes, and the color field minimalist Ellsworth Kelly both covered their Met forms with bold, black, capital letters that look as though written by the same hand.

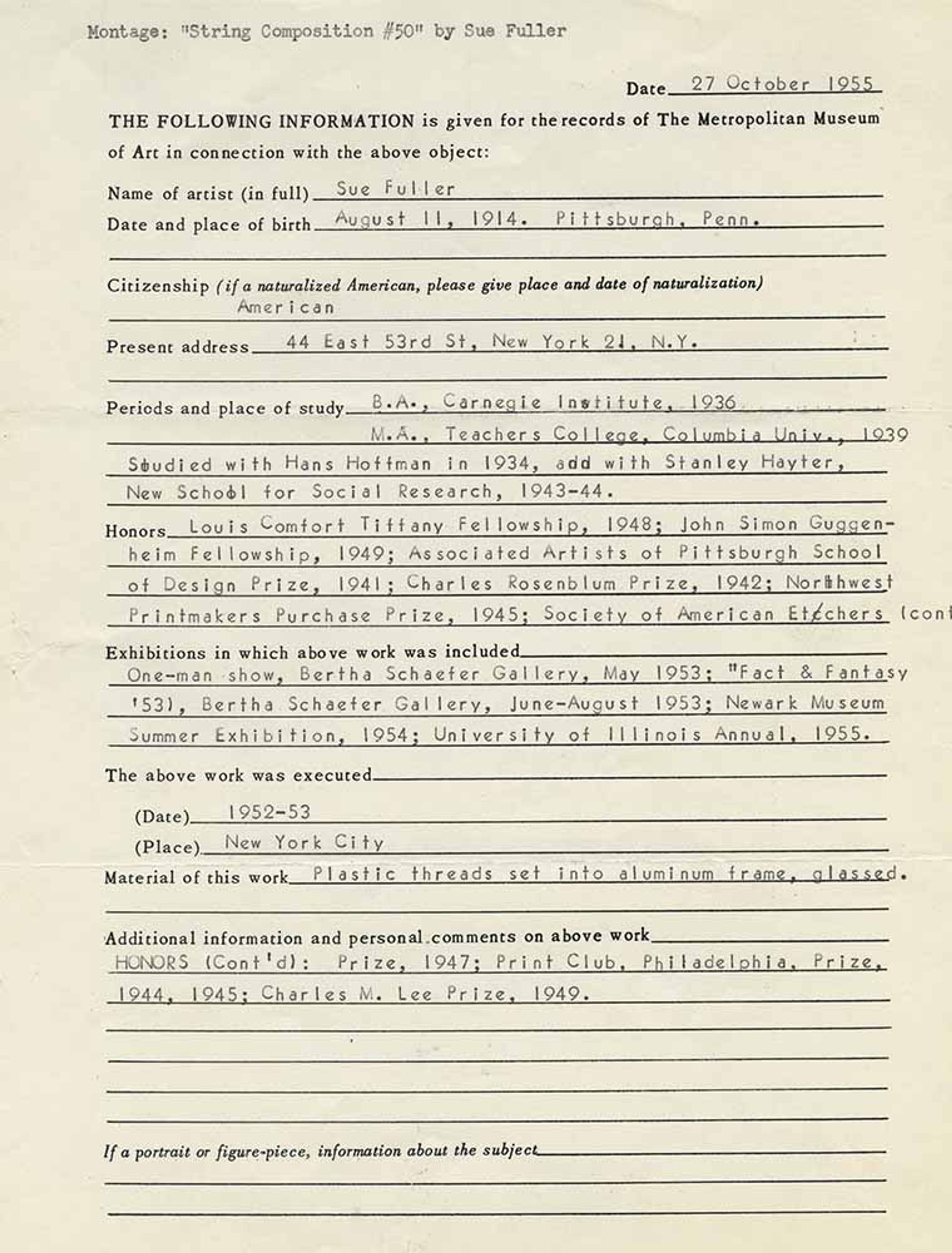

Sue Fuller, Information Form for String Composition No. 50, 1955, Office of the Secretary Records, The Metropolitan Museum of Art Archives.

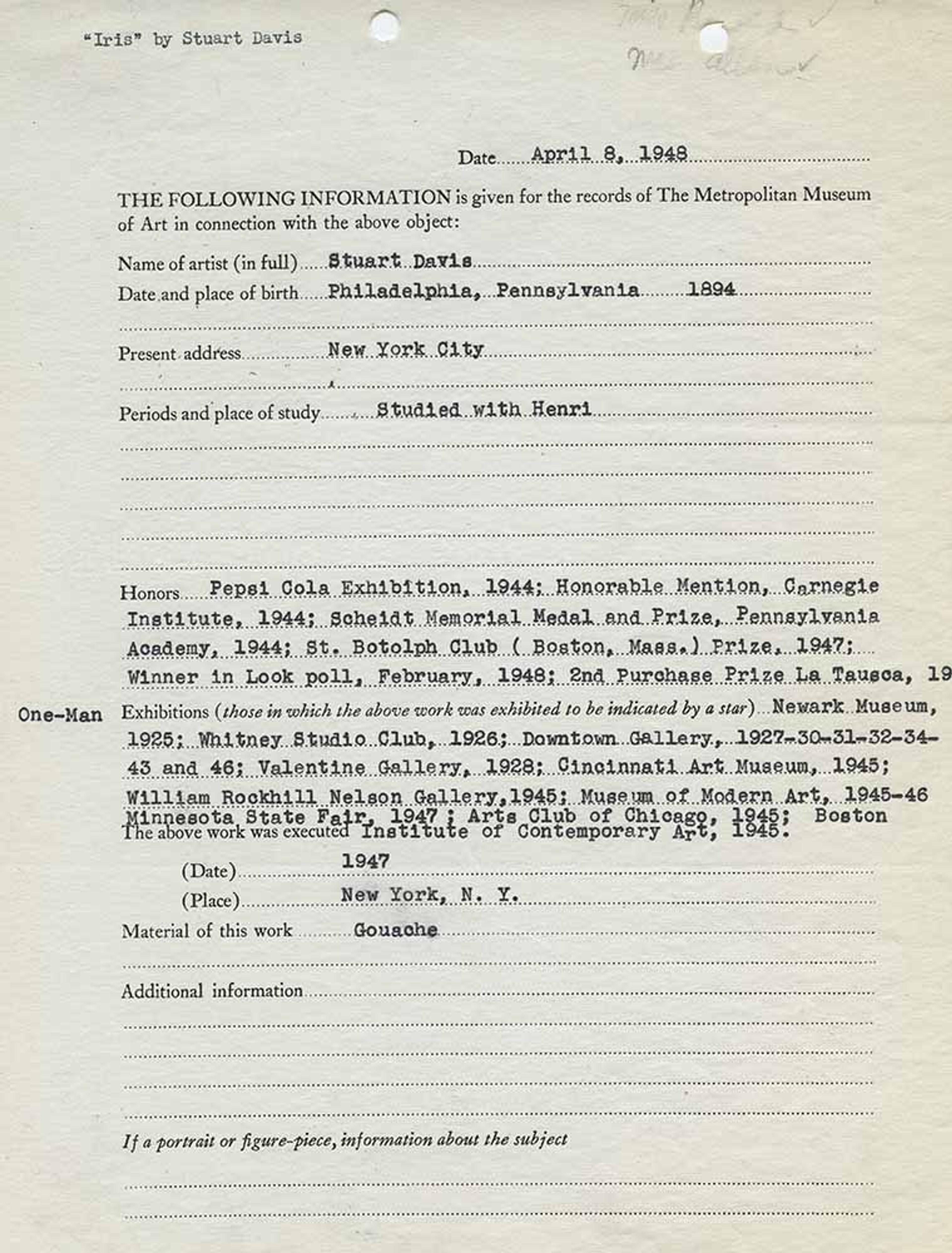

Stuart Davis, Information Form for Iris, 1948, Office of the Secretary Records, The Metropolitan Museum of Art Archives.

Several artists dispensed with pen and pencil altogether, and chose instead to type their responses. These included sculptors Noguchi and Sue Fuller, and the painters Morris Graves, Robert Henri, and Stuart Davis.

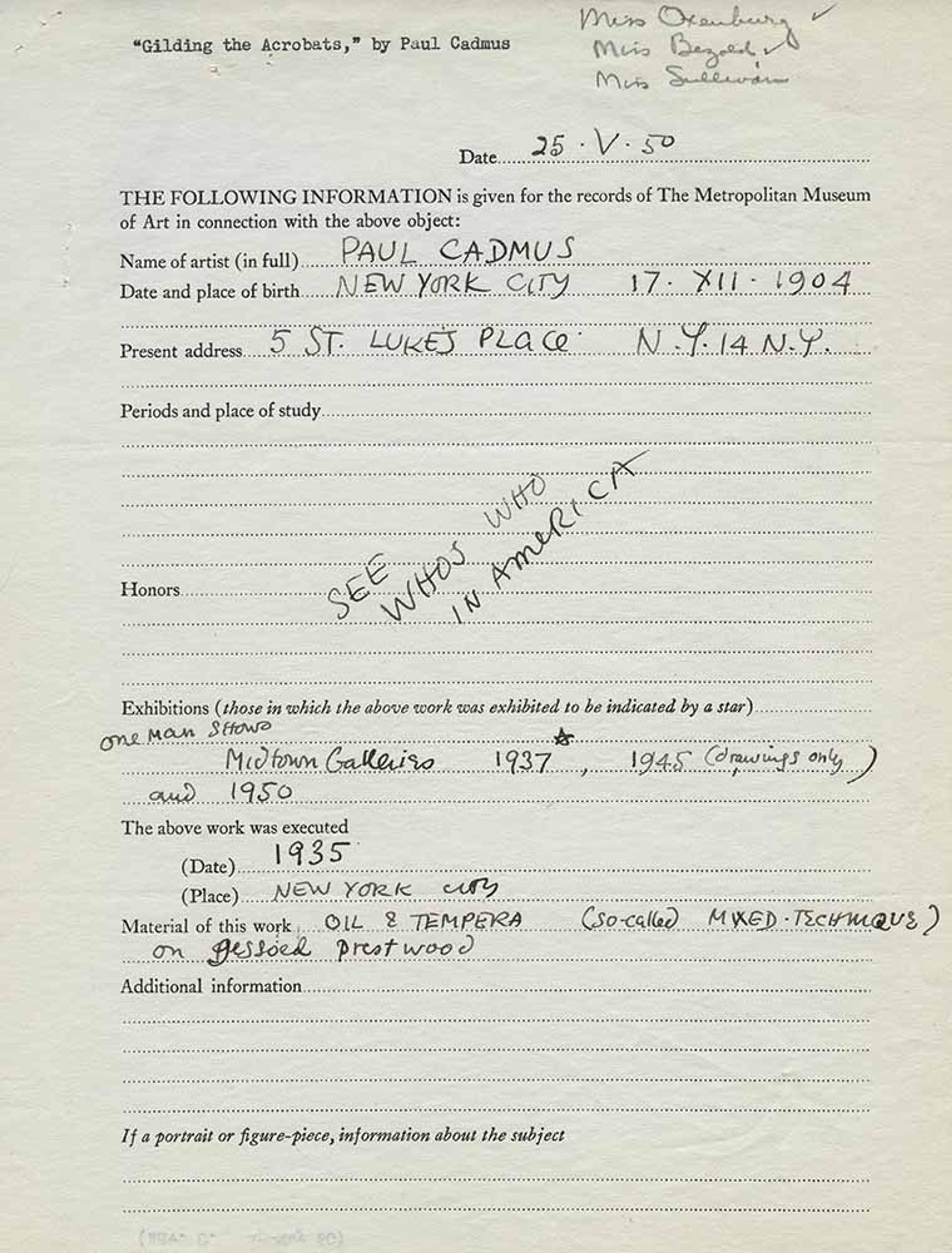

Paul Cadmus, Information Form for Gilding the Acrobats, 1950, Office of the Secretary Records, The Metropolitan Museum of Art Archives.

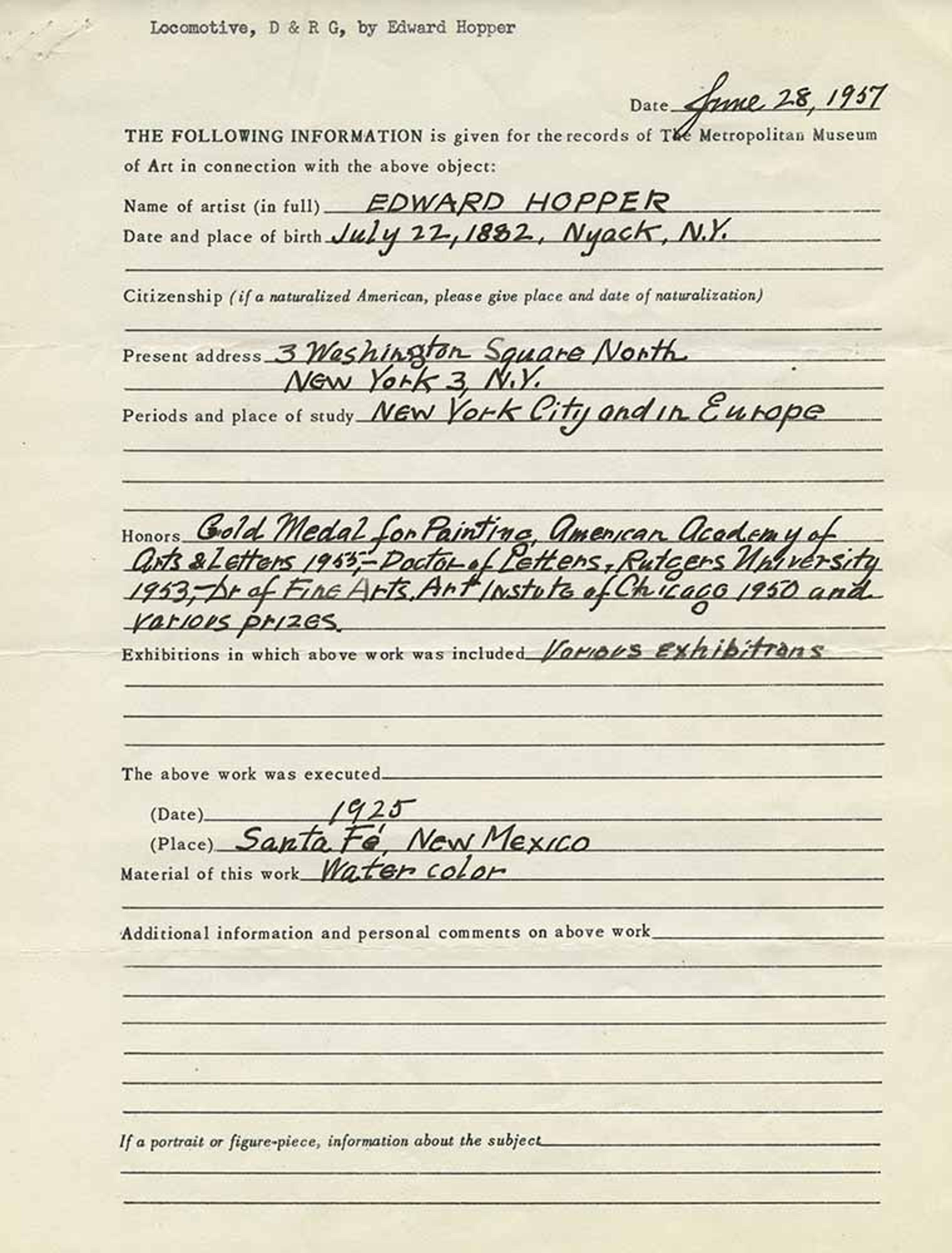

Edward Hopper, Information Form for D. & R.G. Locomotive, 1957, Office of the Secretary Records, The Metropolitan Museum of Art Archives.

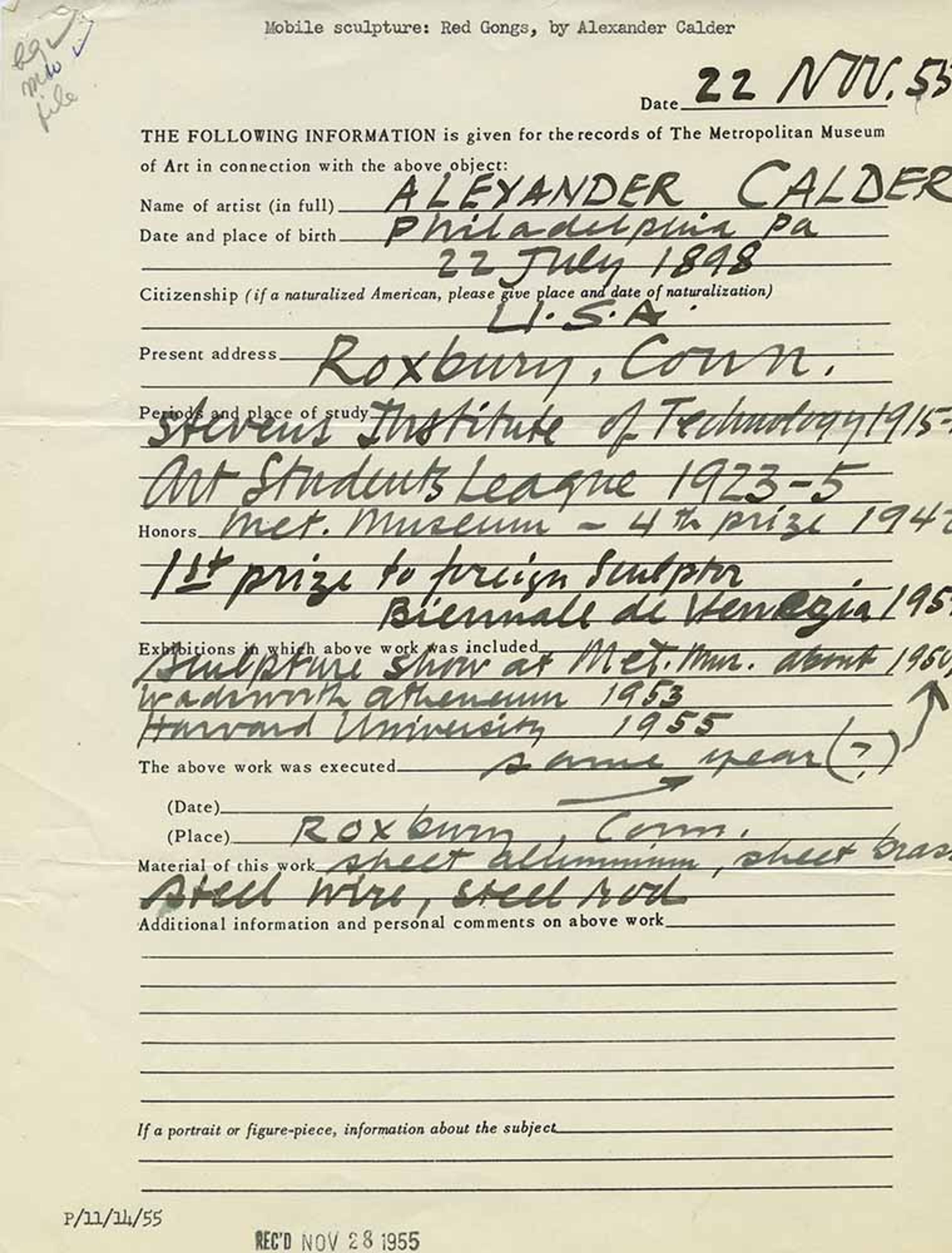

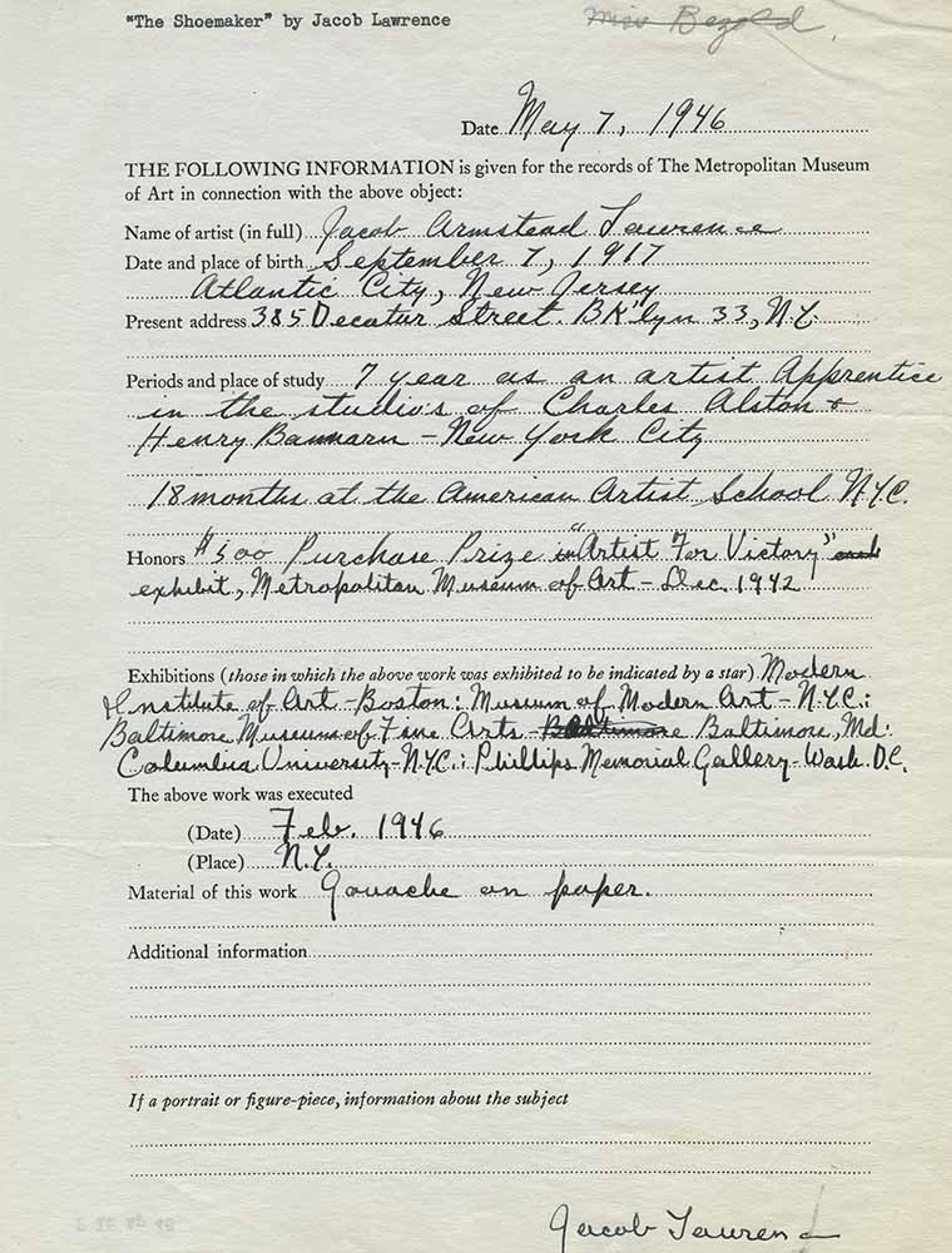

Quite a few of these documents are, frankly, more tantalizing than informative, because they were completed cursorily by artists who chose not to record details about their creative process or to offer interpretations. Paul Cadmus couldn’t be bothered to mention his training at the National Academy of Design and Art Students League, instead scrawling on his form a referral to “See Who’s Who in America.” One wonders if Edward Hopper found such administrative paperwork numbingly bureaucratic, if Jacob Lawrence felt it tedious, or if Alexander Calder thought it intrusive. Perhaps they simply could not find the time to reflect on their art in answer to The Met’s query, as Isamu Noguchi thankfully managed to do.

Alexander Calder, Information Form for Red Gongs, 1955, Office of the Secretary Records, The Metropolitan Museum of Art Archives.

Jacob Lawrence, Information Form for The Shoemaker, 1946, Office of the Secretary Records, The Metropolitan Museum of Art Archives.

The Museum continued to issue information forms to artists newly represented in the collection until the late 1960s, then stopped the practice for reasons that are unclear. In the twenty-first century, curators in The Met’s Department of Modern and Contemporary Art department conduct in-depth interviews with selected artists whose work appears at the Museum, and share the results with a global audience through publications and online videos. Recent subjects include multimedia artist Dan Graham, sculptor Wangechi Mutu, and painter Kent Monkman.