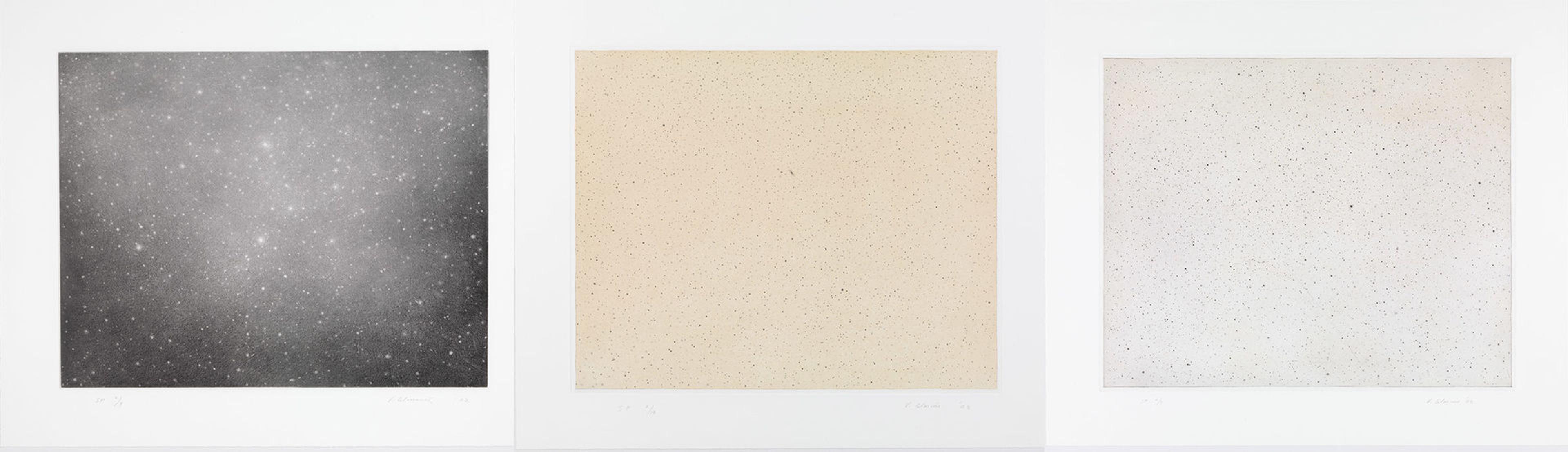

Vija Celmins, (American, b. Latvia, 1938). Night Sky 3. One-color aquatint with burnishing and drypoint, Sheet: 19 ¾ × 23 ¾ in. (50.5 × 60.7 cm) Plate: 14 ¾ × 18 ¾ in. (37.6 × 47.5 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Vija Celmins, 2003 (2003.336.3)

The Latvian American artist Vija Celmins draws inspiration from the natural world: spiderwebs, craterous deserts, the sea, the surface of the moon. In the nineties, she began a series of paintings and photogravures based on photographs of the night sky. Layering solid charcoal onto wrought plates, she uses erasers to map the stars, hazy lights against a worn black. She later imprinted the same pattern on a waxen field, inverting the pattern on a parchment-hued background. Reversed, the night sky resembles a plane of imperial white granite.

I rarely look up at the sky. Perhaps it’s the city lights—unless there’s a full moon, there’s not much to see. Then COVID surfaced this year, along with its forced isolation. Time froze yet trudged obstinately forward, indifferent to my plans. I spent my days watching online classes on an amalgam of subjects: Japanese cultural history, symbolism in ancient Egyptian art, the exploration of time and space. I read books on the bells of Tokyo and how an Amazonian tribe’s intricate language shaped their perception of the world. Many people fled the city, seeking refuge in their native towns or the fresh air of nearby country or beach houses. Meanwhile, I remained in my apartment in Brooklyn, missing Colombia and listening to a professor through a screen describe how we’d immunized ourselves from the night sky.

Left: Vija Celmins, (American, b. Latvia, 1938). Night Sky 3. One-color aquatint with burnishing and drypoint, sheet: 20 × 24 in. (50.5 × 60.7 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Vija Celmins, 2003 (2003.336.3). Center: Vija Celmins, (American, b. Latvia, 1938). Night Sky 2 (Reversed). Three-color photoetching, aquatint, photogravure, and drypoint, sheet: 20 ¾ × 24 ½ in. (52.7 × 62.2 cm. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York Gift of Vija Celmins, 2003 (2003.336.2). Right: Vija Celmins, (American, b. Latvia, 1938). Night Sky 1 (Reversed). Three-color photoetching, aquatint, photogravure, and drypoint, sheet: 21 × 24 ¾ in. (53.3 × 62.5 cm. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Vija Celmins, 2003 (2003.336.1)

Across millennia, people have turned to the night sky for answers, to help with navigation and measure the passage of time. The relative motion of celestial bodies is the reason we define our days and the course of our lives in the way that we do. A day marks the earth’s full rotation on its axis, a year the earth’s journey around the sun, a month the moon’s dance around the earth.

Celmins’s work reminds me that we’ve grown estranged from the stars that featured prominently in our ancestors’ lives. Exploring the instruments and devices people have made throughout history illustrates the timeless desire to make sense of the cosmos. Japanese star mandalas, used in rites to prevent calamities or epidemics, are woven with the Big Dipper and the Nine Luminaries. A Chinese mirror believed to bring life and light into people’s dark tombs is etched with the circular heavens, cardinal directions, and the “twelve earthly branches” used to compute the Chinese calendar. Albrecht Dürer’s fourteenth-century celestial maps are populated with portraits of early astronomers and the roaming creatures of the zodiac.

Left: Star Mandala, Japan, 13th–14th century. (Hoshi mandara zu) (Hanging scroll: Hanging scroll; ink, color, gold, and cut gold on silk, Image: 79 ¼ × 48 ¾ in. (201 × 124 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Sue Cassidy Clark, in honor of Bernard Faure, 2020 (2020.391). Center: Mirror with game board design and animals of the four directions, China, 1st–2nd century. Bronze with black patina, Diam. 6 ¾ in. (16.8 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, Rogers Fund, 1917 (17.118.42). Right: Albrecht Dürer (German, b. 1471). Right: The Celestial Map- Northern Hemisphere, 1515. Woodcut, Sheet: 24 ¼ x 18 in. (61.3 x 45.6 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, Harris Brisbane Dick Fund, 1951 (51.537.1)

For centuries, people have used the sky to tell stories. It was a source of myth but it was also a map, a calendar, a clock. They tracked the movement of the stars, studying their transits to codify patterns and track what today we call time. Our notion of time has evolved, perhaps because the way we talk about it has changed as well. There is time spent, wasted, and lived, time that we kill, use, save, yet don’t have enough of. Time even has agency: it flies, passes, ticks, and elapses. Figuratively speaking, it can also stop. There are different ways of seeing time: when it begins and when it ends, what every passing moment means and how best we may quantify it. It can be linear (a constant flow with no return) or cyclical, establishing patterns and rhythms (weeks, months, years).

In Ancient Egypt, calendars were developed by the middle of the Old Kingdom (circa 2450 B.C.) based on the cycles of the moon and the agricultural seasons. Days began at dawn, weeks lasted ten days, and the end of the month was marked by the waning moon. The seasons, known as Inundation (Akhet), Emergence (Peret), and Harvest (Shemu), lasted four months each and invoked the ebbs and flows of the Nile River. The Egyptians developed shadow clocks and sundials to trace the shadows cast by the sun and track the passing of the hours. [1] The giant obelisks we see today in cities like New York, Istanbul, and Paris are not mere monuments that tell stories and commemorate the gods. These monolithic stones, carried from Egypt as emblems of conquest or the occasional friendly gift, also read the sun’s shadows.

Left: Shadow Clock. Egypt, 306–30 B.C. (Ptolemaic Period). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, Rogers Fund, 1912 (12.181.307). Right: ‘Umar ibn Yusuf ibn ‘Umar ibn ‘Ali ibn Rasul al-Muzaffari (Yemini, ruled 1295–96). Astrolabe of ‘Umar ibn Yusuf ibn ‘Umar ibn ‘Ali ibn Rasul al-Muzaffari, A.H. 690/ A.D. 1291. Brass; cast and hammered, pierced, chased, inlaid with silver, 7 ½ x 6 ¼ in. (19.4 x 15.6 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Edward C. Moore Collection, Bequest of Edward C. Moore, 1891 (91.1.535a–h)

In the medieval Islamic world, calculating the location of heavenly bodies was also significant because of the requirements of Islam. The fixed stars and the passage of the sun helped determine the time of day for prayer (as well as one's orientation toward Mecca), and the moments of sunrise and sunset for fasting during Ramadan. Astrolabes measured time based on the height of the sun or the stars and ephemeris tablets charted the location of celestial bodies at any given time. [2]

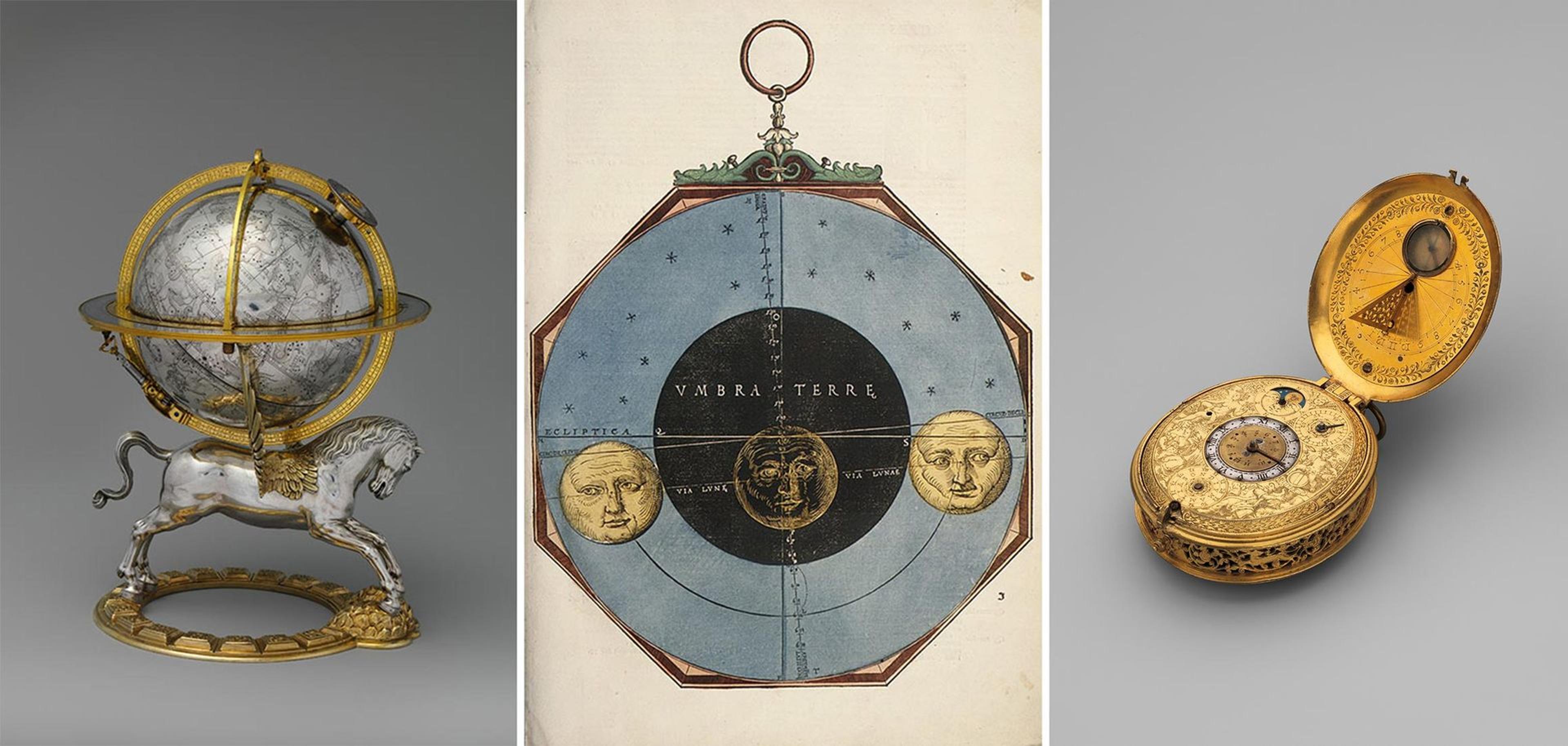

The first mechanical clocks appeared around the second half of the thirteenth century. While they were a tool for timekeeping, clocks also showcased status and mastery over the natural world. During the late Renaissance, clocks commissioned for royal European Kunstkammern symbolized their owner’s wealth and broad humanist education. Along with other timekeeping and scientific instruments, they were considered scientifica or “the testaments of man’s ability to dominate nature.” [3]

Left: Gerhard Emmoser (German). Celestial globe with clockwork, 1579. Austrian, Vienna. Partially gilded silver, gilded brass (case); brass, steel (movement); 10 ¾ × 8 × 7 ½ in. (27.3 × 20.3 × 19.1 cm); diameter of globe: 5 1/2 in. (14 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of J. Pierpont Morgan, 1917 (17.190.636). Michael Ostendorfer (German). Center: Astronomicum Caesareum, 1540. Hand-colored woodcuts, 17 ¾ × 12 ¾ × 1 5/16 in. (45.4 × 32.3 × 3.3 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Herbert N. Straus (1925, 25.17). Jan Jansen Bockeltz (Dutch). Right: Clock-watch with sundial, ca. 1605–10. Gilded brass, silver, blued steel, copper, 3 ½ × 2 ½ × 2 ¼ in. (8.9 × 6.2 × 5.9 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of J. Pierpont Morgan, 1917 (17.190.1603)

Different cultures perceived time in different ways. Rome had an eight-day week, the Aztecs had a five-day week, and the Babylonian week was composed of ten days. Calendars varied, and the beginning of time was often tied to a significant event. The Roman calendar begins with the apocryphal founding year of Rome, the Islamic calendar begins with emigration of the Prophet Mohammed from Mecca to Medina, and until 1961, the Korean calendar calculated time from the beginning of the Gojoseon Kingdom in 2333 B.C. The Christian calculation of time likewise stems from the birth of Christ.

Depending on the language you speak, days can be long or full, breaks can be short or “small,” upcoming weeks can be defined as “next” or “down.” You can be “on” or “in” time. Language impacts our perception of time. You can have one word to blanket every notion of time or, as in Japanese, you can divide it into time’s smallest fraction (the setsuna), the vastness that stretches out toward eternity (ko), and the time used in stopwatches and races (ta-imu). [4]

Even the days of the week are tied to the sky. In English, the word “Sunday” derives from the sun, “Monday” from the moon. Weekdays are named after planets, which in the Roman calendar are named after the gods Mars, Mercury, Jupiter, and Venus. This link is visible when you read the days of the week in Spanish: martes, miercoles, jueves, viernes. In English, we find vestiges of what the Germans deemed the Roman gods’ teutonic counterparts: Tiw’s day (Tuesday), Thor’s day (Thursday), Wodan’s day (Wednesday), and Freya’s day (Friday).

I’ve spent my days in technical time, developed around the end of the thirteenth century to organize the rhythm of prayer and calculate “canonical time” in European monasteries. It uses mechanical clocks, differentiates the length of the summer hour from that of winter, and employs a system rooted in the Royal Observatory based in England (Greenwich mean time).

But clocks are fickle. Einstein’s theory of relativity posits that time slows near anything heavy. On earth, for example, clocks run more slowly at sea level, nearer the earth’s massive core than on mountaintops. Clocks on satellites run much faster. Does this mean that time speeds up at mountaintops? Or is it simply that our tools for quantifying time speed up at mountaintops, fallible and susceptible to the laws of physics and gravity?

Right: Half-hour sandglass, German, ca. 1500–25. Gilded silver, gilded bronze, 3 ¼ × 3 ¼ in. (8.3 × 8.4 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Samuel P. Avery, 1912, (12.23.1)

Most of the people I know cycle through life setting alarm clocks, setting personal or professional deadlines, thinking that our age or the time when we accomplish something determines its value. There’s a duality in our relationship with time. On the one hand, it goes by too fast. On the other hand, when it’s pitted against expectations and aspirations, it can’t go fast enough.

Perhaps measuring and quantifying time is a way of giving us some sort of control over its inalterable course. In a way, time is linked to inevitable notions of death and impermanence. I look at these objects and I’m fascinated by their beauty and intricate craftsmanship, finely inlaid silver and gilded brass. They’re cutting edge, records of the way people have tried to capture the elusive nature of time. But just like various cultures have rituals believed to impact the weather, cosmos, and the will of the gods, perhaps these objects are our way of exerting control over something relative, fleeting, and ultimately, intangible.

Sources

[1] Kamrin, Janice. “Telling Time in Ancient Egypt.” In Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000– (February 2017). Return

[2] Sardar, Marika. “Astronomy and Astrology in the Medieval Islamic World.” In Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000– (August 2011). Return

[3] Koeppe, Wolfram. “Collecting for the Kunstkammer.” In Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000– (October 2002). Return

[4] Anna Sherman, The Bells of Old Tokyo (Picador, 2019). Return