Photo by author

«As a postdoctoral fellow, I have been tasked with researching our Modern and Contemporary Art collection, enhancing our object files, and preparing a wealth of information for publication online. And while this remains an exciting time to be involved in this department—which will soon expand into The Met Breuer and, later, a new wing in the Met's Main Building—I must admit that I believe the Museum's most fascinating and impressive holdings in contemporary art remain hidden in the library stacks.»

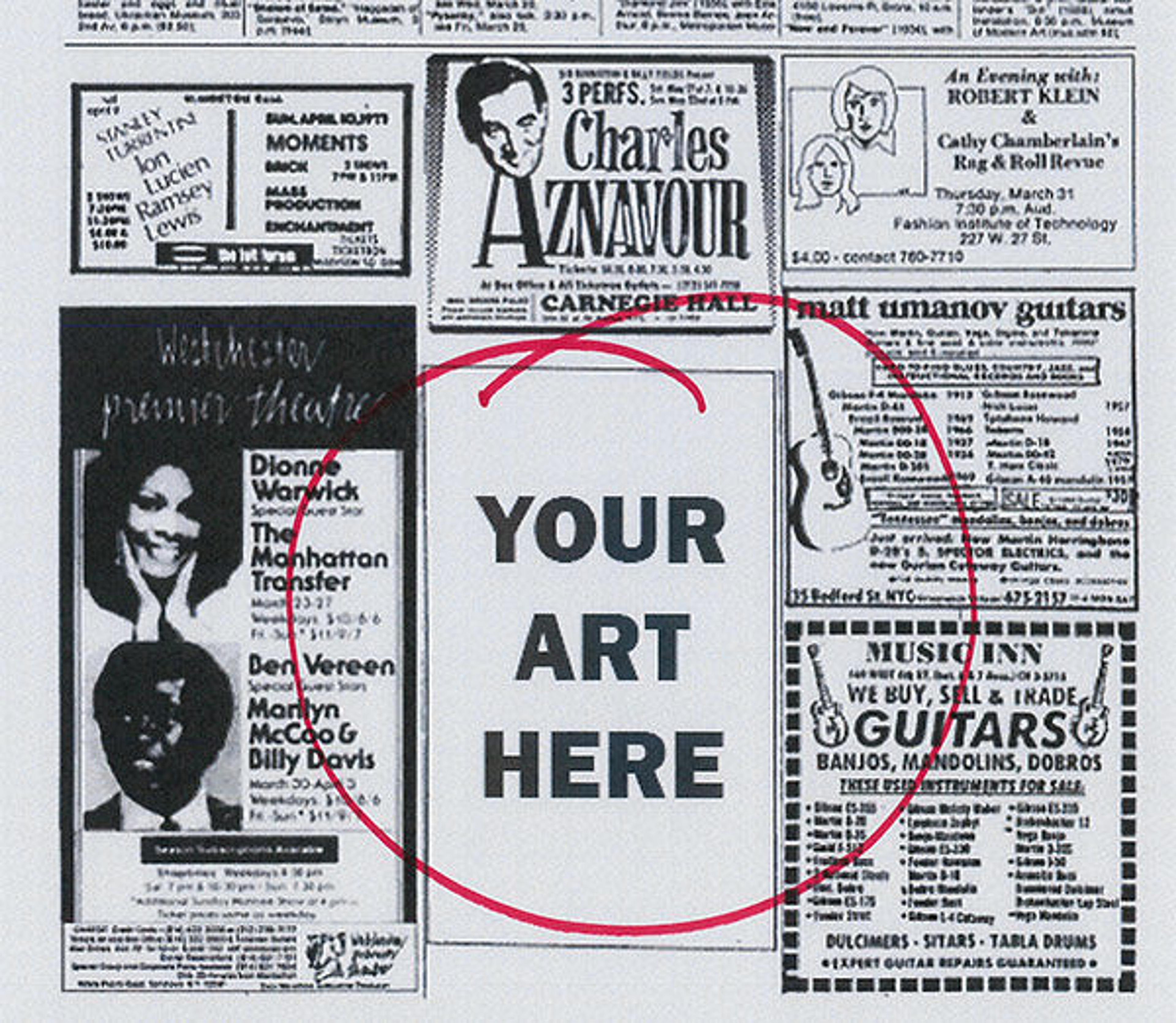

As a doctoral student and, indeed, now in my independent scholarship, my focus is advertisements, specifically print advertisements created by artists as works of art in their own right. What does this mean? This rubric does not encompass Pop artists like Andy Warhol or Roy Lichtenstein, who incorporated comics or advertisements into their work in more traditional media like drawing or painting. Rather, "ad art" refers to site specific works that take advantage of the inherent ephemerality and authority of print periodicals—particularly renowned publications like Artforum and the Village Voice—while simultaneously co-opting their mass distribution network to foster an intimate, one-on-one engagement with a wide range of new (and usually highly receptive) viewers. The best examples of this practice transcend their commercial setting and present "artist pages" that range from the self-promotional to the satirical, the conceptual to the comic. By skirting the traditional channels controlled by the gallery, curator, collector, dealer, and critic, artists used "ad art" as an immediate, incisive way to address the myriad social, political, and cultural changes that emerged in America in the 1960s and 1970s.

Last month I had the distinct pleasure of being able to use Watson Library's excellent periodical collection to give an informal lecture on this topic to some of my colleagues. It was thrilling not only to be able to talk about this new avenue of research—which few have studied thus far and therefore remains almost as "out there" as the ads were themselves in their day—but to be able to reveal to other Met staffers yet one more way in which the Museum's wide-ranging collecting practice can flex its muscles.

Though the subject of "ad art" could take up a whole book (I did write my dissertation on it after all!) the examples in our collection tend to break down into several overarching categories—namely conceptualism, artistic self-fashioning, and parody. The following ads represent the most prominent examples of work created in these modes in the 1960s through the early 1980s. "Ad art" started to be sanctioned after this point, and even commissioned by art magazines, engendering further interesting examples but ones which lacked the cutting-edge surprise of their predecessors.

Conceptualism

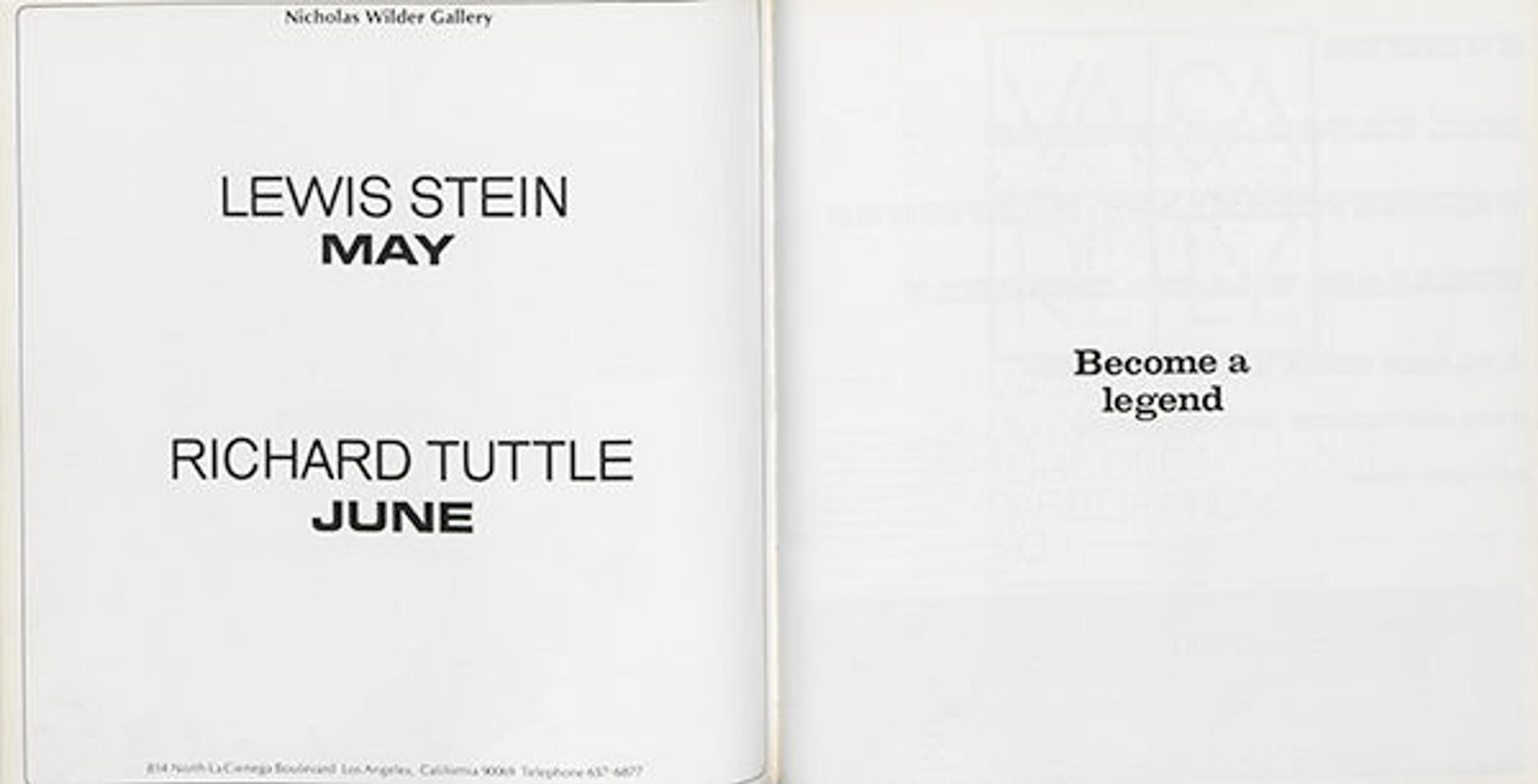

Stephen Kaltenbach. "Become a legend" advertisement. In Artforum 7, no. 10 (Summer 1969): 11.

Between November 1968 and December 1969, Stephen Kaltenbach took out twelve advertisements in the pages of Artforum. These "micro-manifestos" represent the epitome of conceptual art—both graphically and intellectually—with their direct, declarative, and authoritative aphorisms reproduced in a sober black typeface on a white background. 1

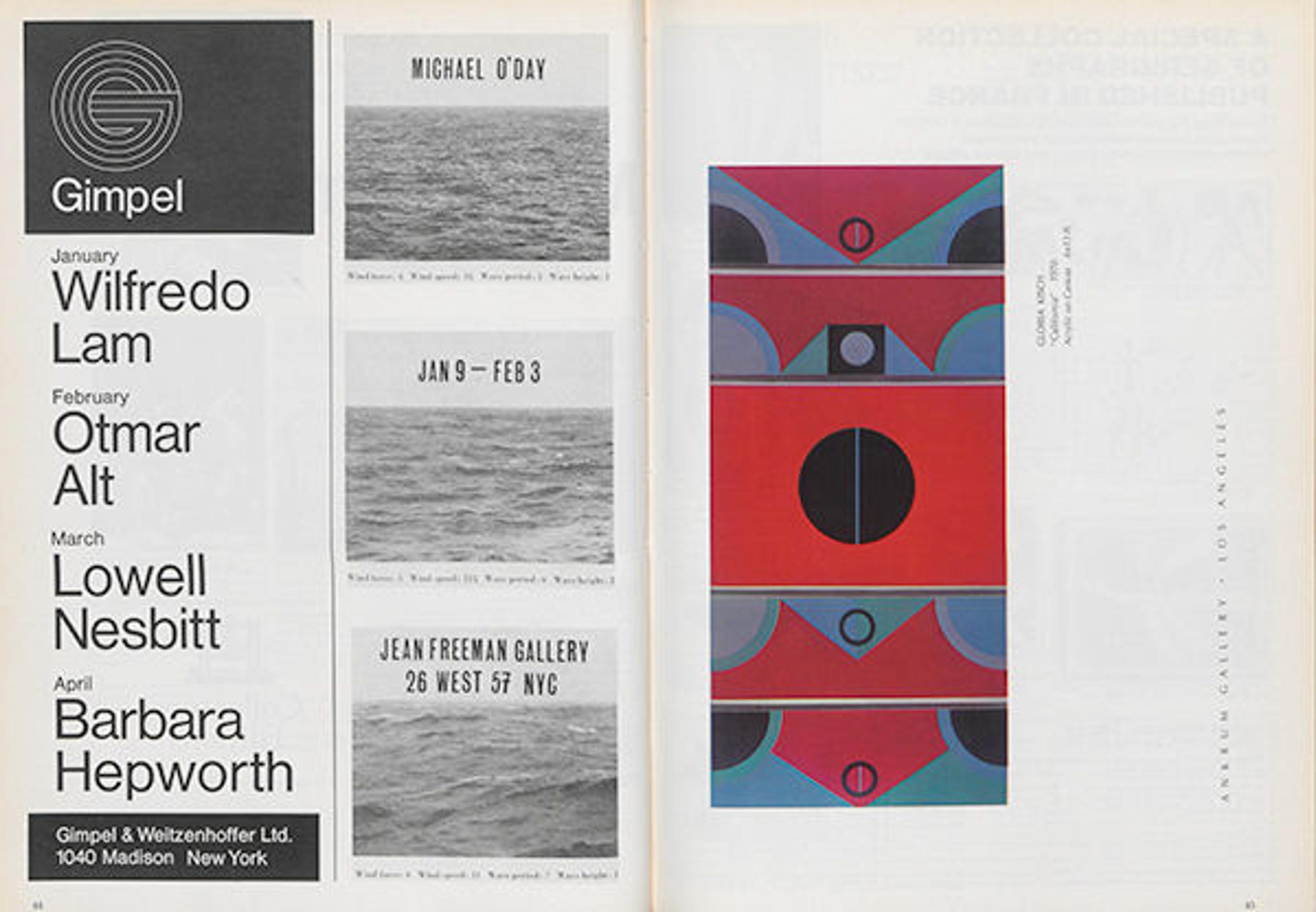

Terry Fugate-Wilcox. "Michael O'Day" advertisement. In Art in America 59, no. 1 (January–February 1971): 44.

Though little-known today, artist Terry Fugate-Wilcox made a major splash in the 1970s New York art world. Disgusted by the growing commercialization of the art market in the late 1960s, Fugate-Wilcox set up an elaborate hoax to expose the art world's increasingly superficial and avaricious ways. He created a conceptual organization called the Jean Freeman Gallery, which included a fictitious address, phone number, bank account, and even imaginary artists. (Fugate-Wilcox created the work himself under the auspices of different artists' names.) The gallery was substantiated by a series of bold, engaging advertisements placed monthly in all the major art publications, including Artforum, Art in America, and ARTNews. The hoax was a roaring success; his nonexistent exhibitions received positive reviews in prominent periodicals, leaving collectors clamoring to own a work by these (unbeknownst to them) nonexistent artists.

Artistic Self-Fashioning

Artists working in Los Angeles in the early 1960s had a tough row to hoe: though Southern California was full of sunshine and opportunity, its burgeoning art world remained entrenched in its conservative ways. This afforded young artists the freedom to experiment (no one was watching anyway) but little power to flourish into a celebrity as their colleagues in Hollywood next door could. Hence many artists turned to the power of advertising—a self-directed, yet highly public form of communication—to get recognized and define their identity in the public eye.

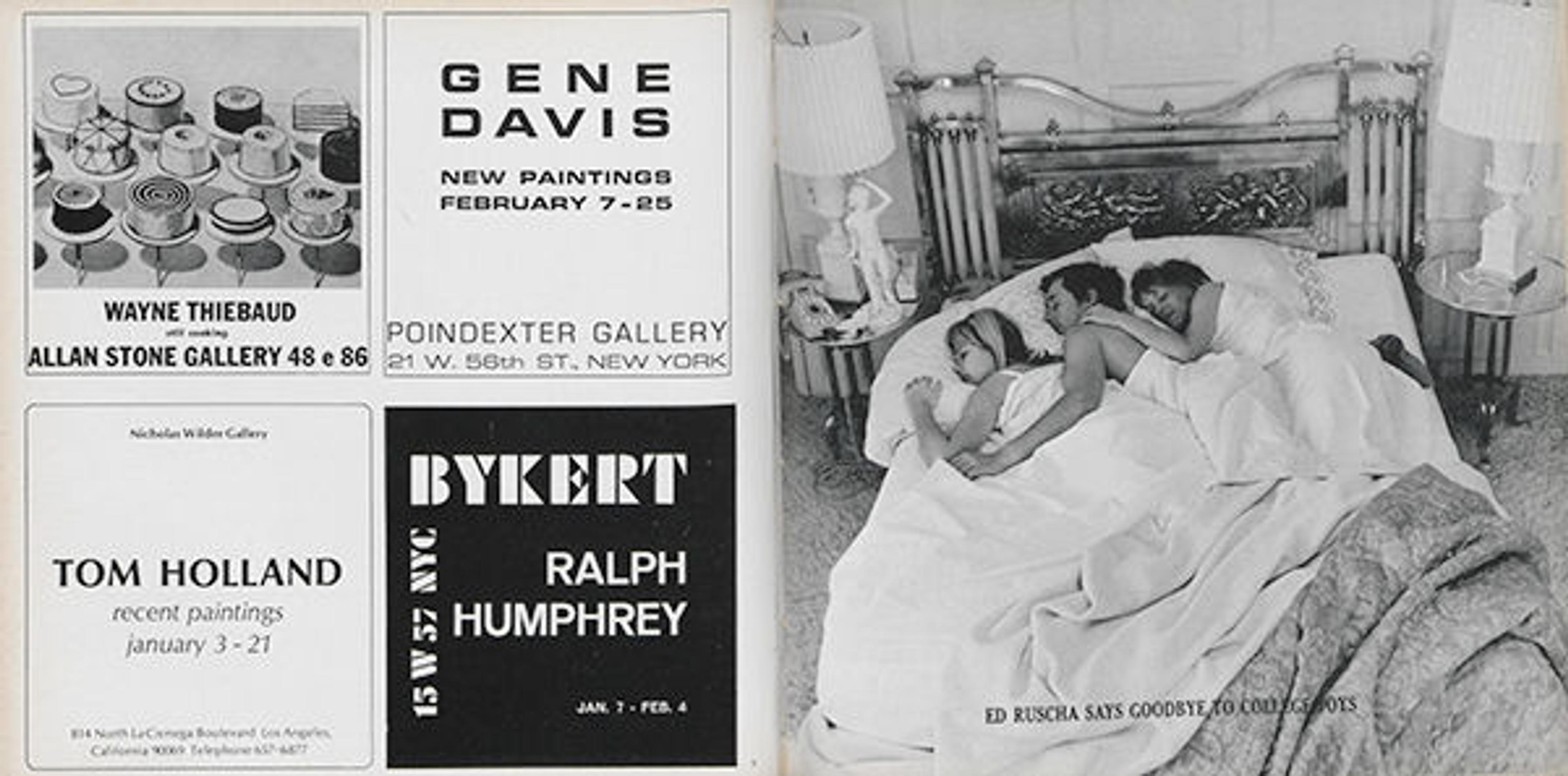

Ed Ruscha. "Ed Ruscha Says Goodbye to College Joys" advertisement. In Artforum 5, no. 5 (January 1967): 7.

Artist Ed Ruscha, who worked doing layouts for Artforum while it was still housed in Los Angeles, used this and several other ads in the mid-1960s to cultivate his public image as a cheeky lothario. Taken out as an ersatz "marriage announcement" just one month before he was to wed sweetheart Danna Knego, Ruscha is seen here in bed with two women—neither of whom are Knego—amidst a tumble of sheets, used tissues, and nude carvings (both in the putti on the headboard and the statue on the side table). As if the nature of the scene weren't explicit enough, the caption at the bottom reminds us that Ruscha has enjoyed his fair share of "college joys," and is only ready to put them away at the advanced age of twenty-nine.

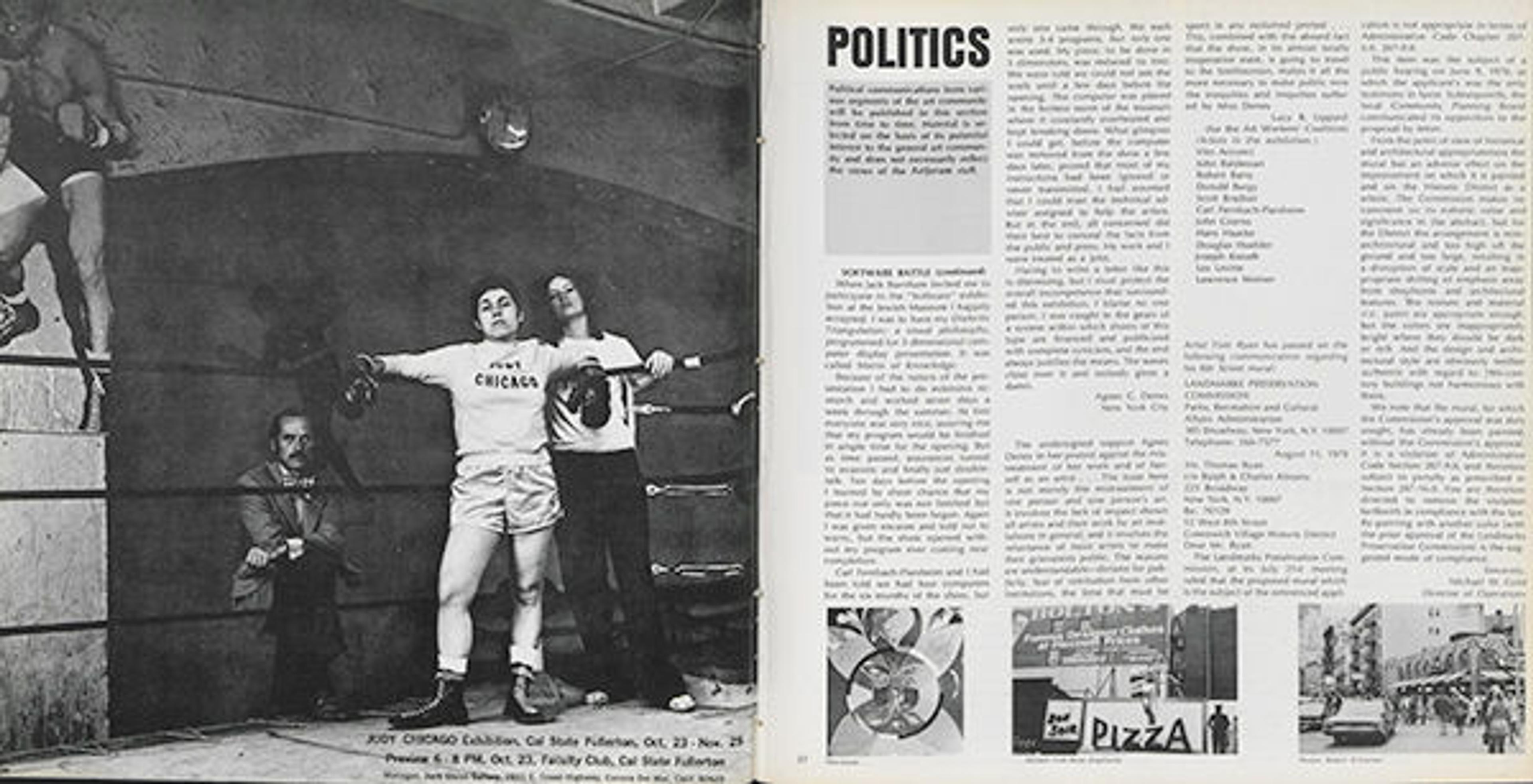

Judy Chicago. Untitled advertisement. In Artforum 9, no. 4 (December 1970): 36. Photograph by Jerry McMillan

Judy Chicago, previously known as Judy Gerowitz, gained fame as a staunchly feminist artist. But before starting the historic Feminist Art Program at Fresno State, Chicago was a fledgling Minimalist, trying to fit in with her fellow SoCal "Finish Fetish" artists, all of whom were male and, like their friend Ruscha, defined themselves by their personal and professional machismo. Chicago took out this now-iconic feminist ad as a type of public service announcement, not only taking her colleagues to task for their sexist ways but as a means to renounce her former married name of Gerowitz and re-brand herself with the new take-no-prisoners identity of "Judy Chicago" (a nod to her birthplace and its tough-guy reputation).

Parody

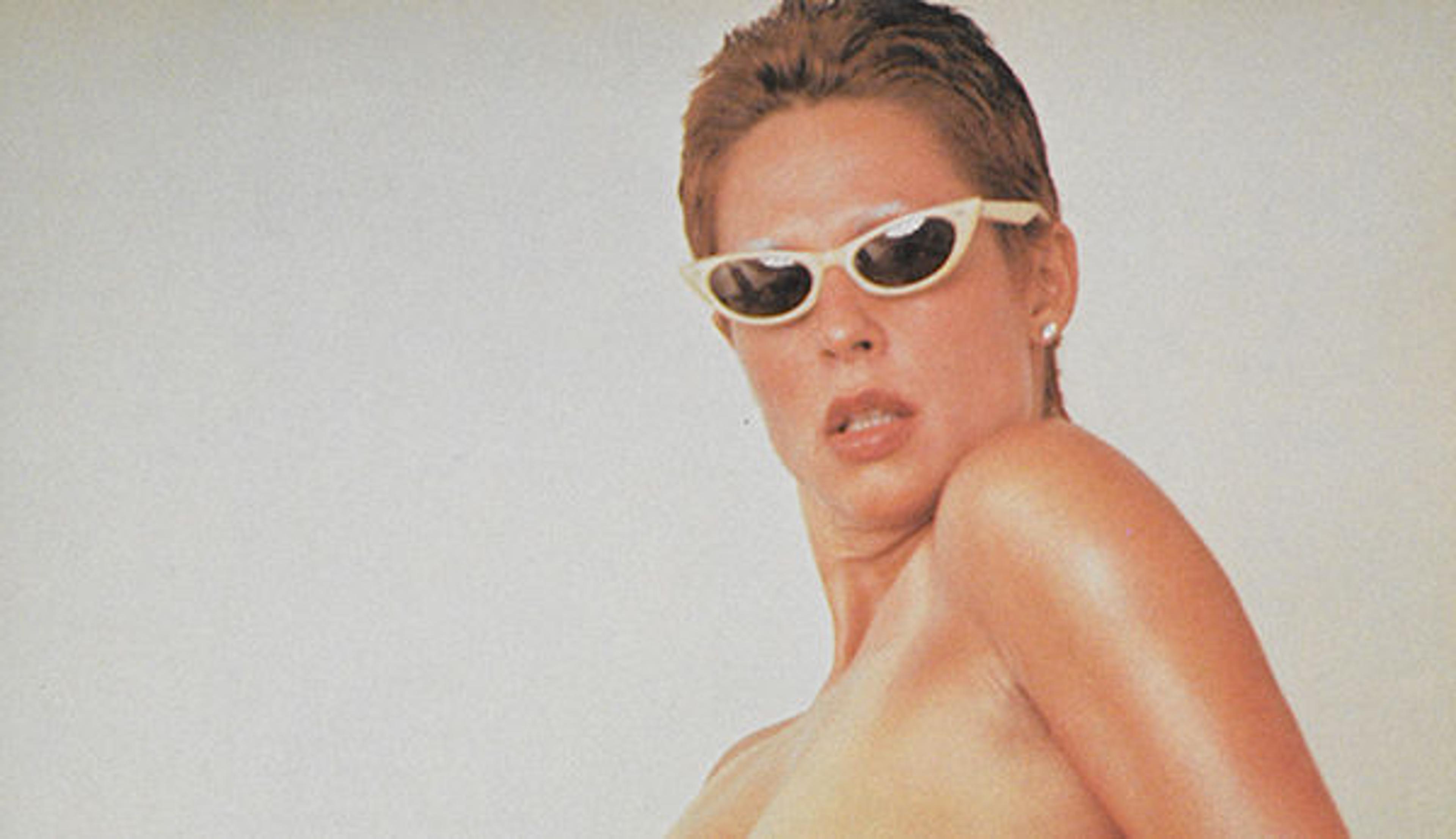

Lynda Benglis. Untitled advertisement. In Artforum 13, no. 3 (November 1974): 4-5. See full NSFW image here.

It never hurts to end with a bang, right? Not surprisingly, many people who have never heard of "ad art" have heard of this work. The outlandish spread was created by sculptor and video artist Lynda Benglis for the November 1974 issue of Artforum. Though many know about the controversy it caused—eighty percent of the editorial staff wrote in to protest the work as "vulgar" and offensive, and it eventually led two editors, Rosalind Krauss and Annette Michelson, to quit and form their own art journal, October—few know about its important precursors. Benglis spent the months leading up to the infamous "dildo" ad's publication creating other ephemeral works that equally experimented with the boundaries of taste, sexuality, gender, and identity.

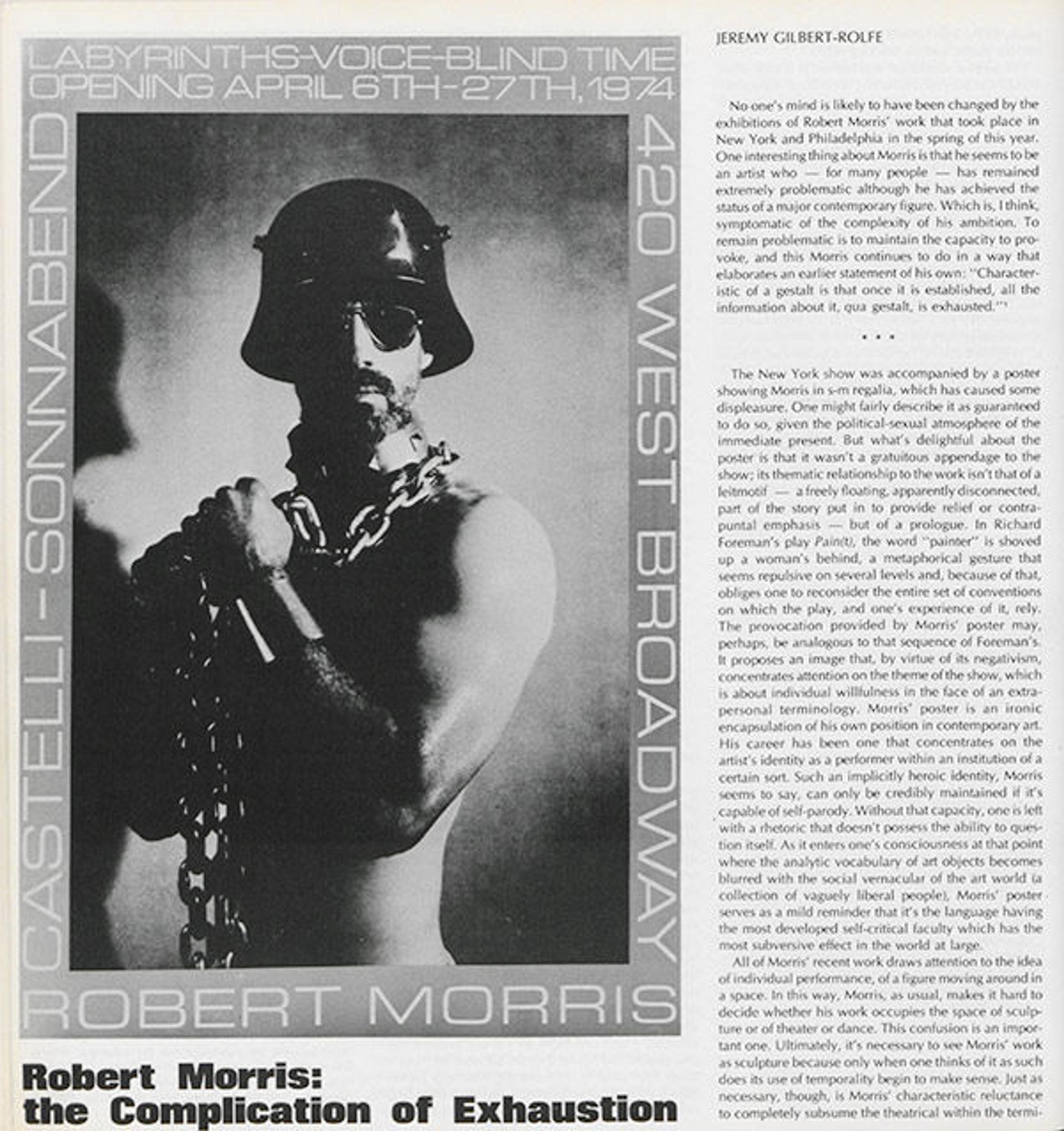

Robert Morris exhibition poster. In Artforum 13, no. 1 (September 1974): 44. Image of reproduction printed in Jeremy Gilbert-Rolfe's Robert Morris: The Complication of Exhaustion

At the same time, Benglis was also collaborating with artist Robert Morris, who created his own pinup-like announcement for an April 1974 exhibition at the Castelli-Sonnabend Gallery. This was later published alongside an article in the September 1974 issue of Artforum, but shockingly created no controversy whatsoever. (This may have to do with the fact that he was having an affair with Artforum editor Rosalind Krauss.) Instead, the satire behind Benglis's ad, which questioned the magazine's conflicted claims of academic superiority and commercial hegemony, exposed the cracks in the periodical's imposing facade and established her reputation as an enfant terrible that continues even today.

[1] Kaltenbach, quoted in Gwen Allen, Artists' Magazines: An Alternative Space for Art, 39. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2011.

Related Link

In Circulation: "Are You Serials?!" (Sept. 30, 2015)