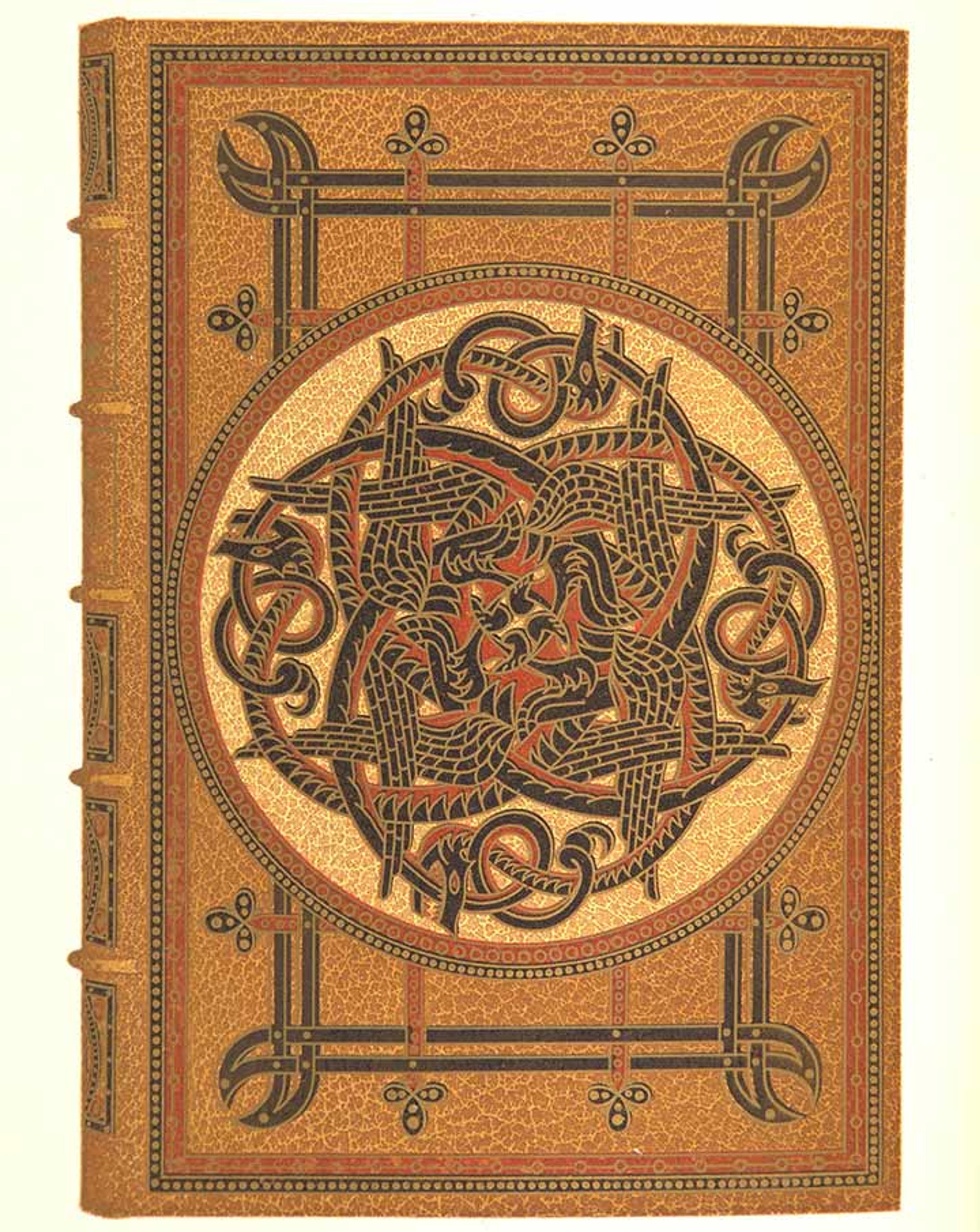

Print depicting the frontispiece of a fine binding for the Völsunga Saga, bound by Bradstreet's. Design and execution attributed to Alfred Launder. From Catalogue of the Library of Henry W. Poor, Part V. New York: The Anderson Auction Company, 1909. Image courtesy of the Department of Drawings and Prints Reference Library

«Since coming to The Met in 1981, I have surveyed and conserved thousands of the Museum's bookbindings and studied its rich collections on book history and technique. One of our most notable treasures is an annotated typescript of an unpublished treatise on book repair, A Textbook for Rebinding Rare Books, Based on a New Technical Principle. This manuscript was painstakingly created by the Museum's first bookbinder, Alfred William Launder, who began his employment at the Museum in 1929 at the age of 62, a time when most people would be considering retirement.»

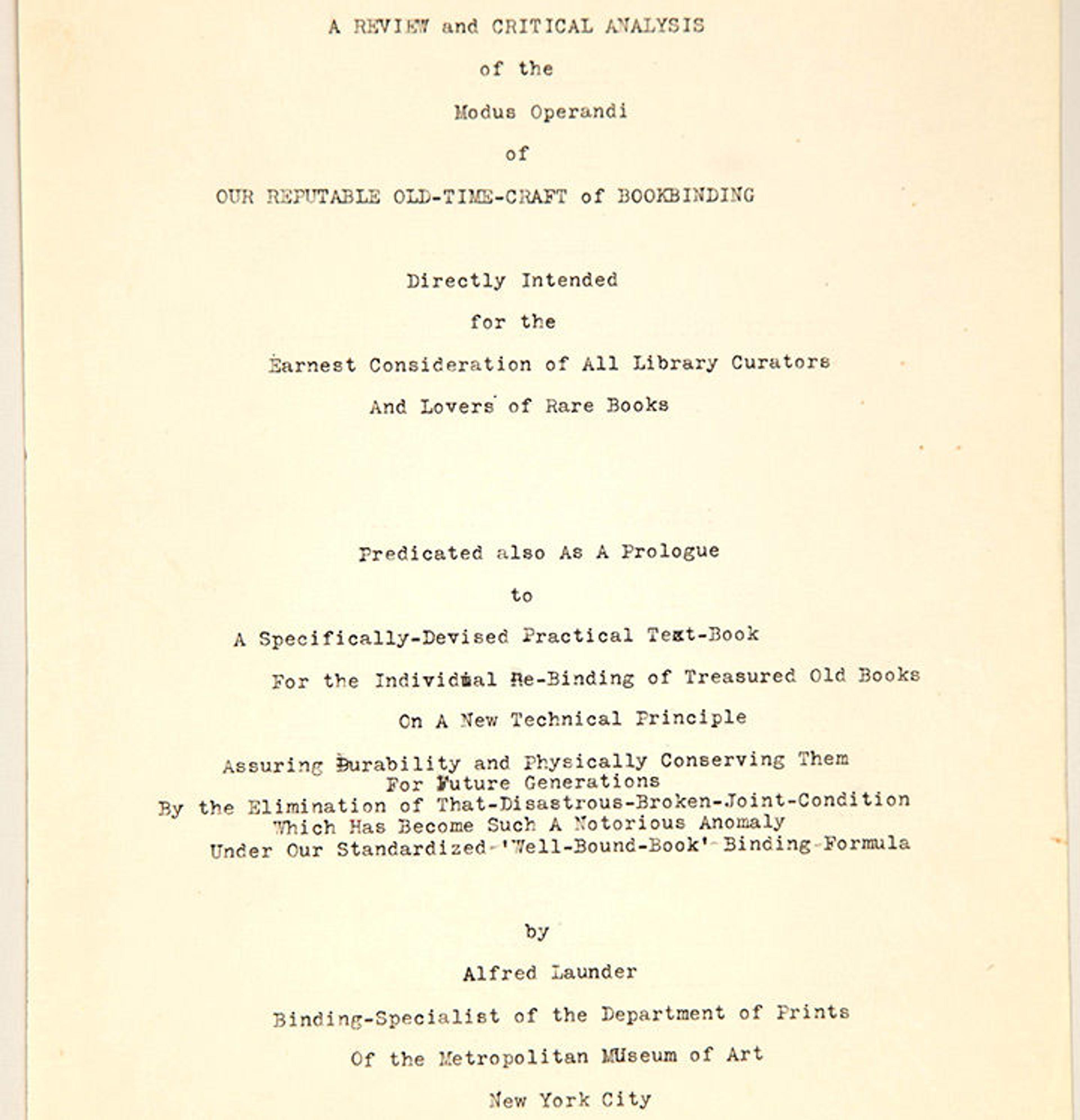

This manual, radical in its time, would have been the first book-conservation manual had it been published as intended in the 1940s. It fervently challenged the commercial bookbinding establishment for its inability to create durable, well-bound books and laid out new techniques for the creation of flexible and durable conservation bindings. The manuscript and its accompanying correspondence have recently been digitized in their entirety as part of Watson Library's Digital Collections.

Title page of Alfred Launder's typescript of his manual, A Textbook for Rebinding Rare Books, Based on a New Technical Principle. Watson Library Special Collections

As a binding specialist at the Museum, Launder was responsible for binding, repairing, and rehousing a substantial collection of rare, early printed books in the collection of the Department of Prints, which was established in 1916 under the direction of the great collector and historian William Ivins, Jr. During his time at the Museum (1916–1946), Ivins created one of the nation's pre-eminent collections of prints and illustrated books, consisting of 150,000 works, which include European and American illustrated books, art manuals, ornament books, and trade catalogs dating from the 15th to the 20th century—many in their original or early bindings.

From the beginning, Launder was encouraged by Ivins and others to develop new approaches and methods for binding and repairing books that would provide maximum visual access to text and preserve the original aesthetic and structural integrity of the books. This was quite a challenge at a time when there was no such field as book conservation and contemporary binders were engaged in binding techniques that favored aesthetics over structural integrity. This new idea of binding in service to the text was a different kind of challenge for Launder, and he took it up enthusiastically and with great innovation and success.

Prior to his work at the Museum, Launder, a Londoner, had been a lifelong fine binder and finisher who had achieved the highest level in his trade. As a finisher, he was exclusively responsible for the design and decoration of bindings, including the decorative leather onlays, inlays, and gold tooling. Launder came from a family of bookbinders, and as a young man he apprenticed in his father's shop before later working for the Mansell Bindery, an old and prominent London bindery/stationer.

Alfred's brother William immigrated to America in the 1870s and was hired by Lippincott's, a Philadelphia publishing firm, to establish a bindery for the purpose of creating artistic fine bindings for display at the 1876 Philadelphia Centennial Exposition. William later established a successful commercial bindery in New York City with the Scottish binder James Macdonald. At some point in the late 1800s, Alfred followed his brother to New York and attempted to work for his commercial bindery. He soon found that he was more temperamentally and technically suited for a smaller shop where he could work on bespoke fine bindings without the intense pressures of a commercial trade bindery.

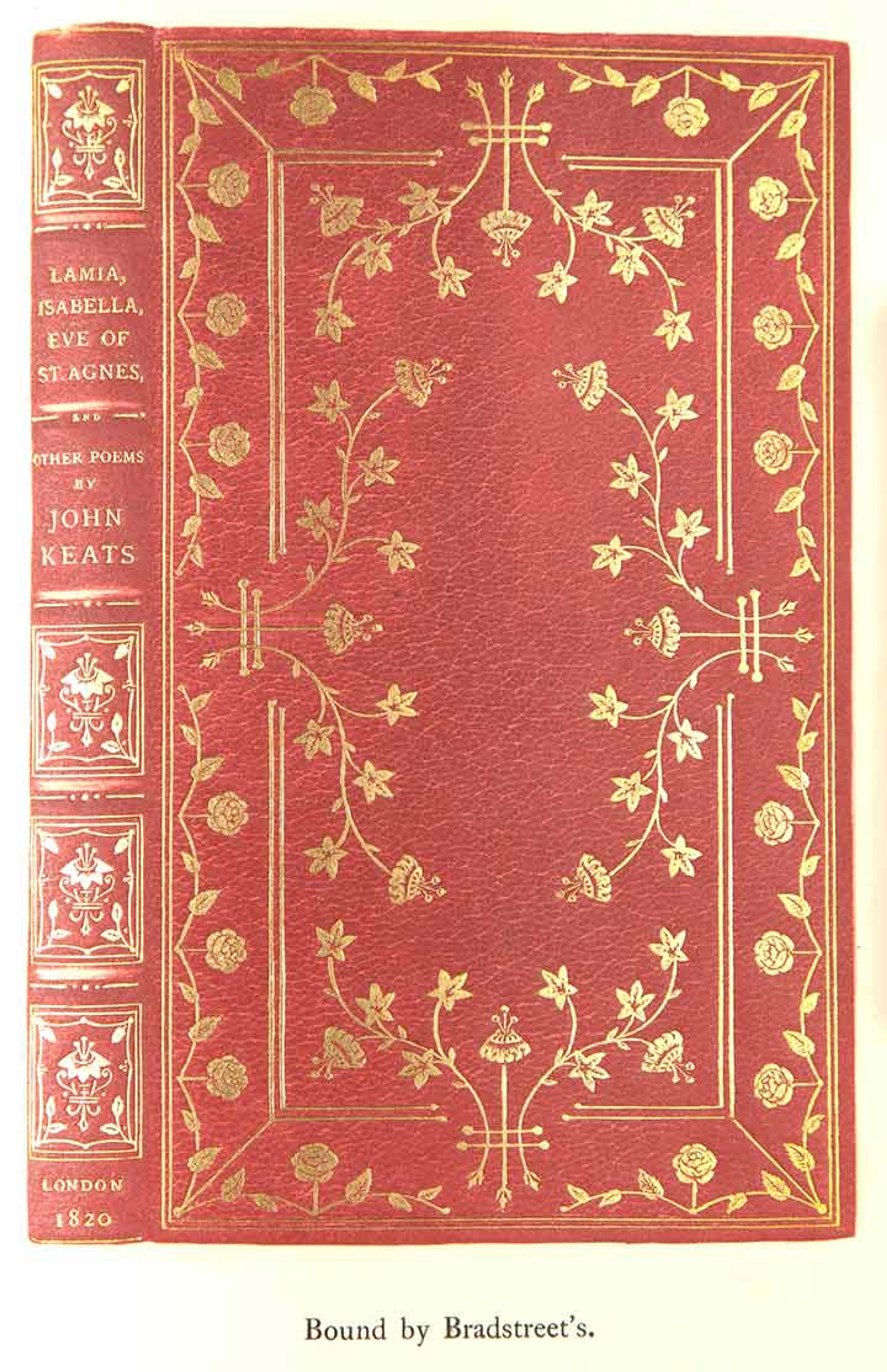

A print depicting a Bradstreet's fine binding on Keats's Lamia, Isabella, The Eve of St. Agnes, and Other Poems (1820). Design and execution attributed to Alfred Launder. From Henri Pène Du Bois, American Bookbindings in the Library of Henry William Poor . . ., plate, opposite page 44. New York: George D. Smith (Marion Press), 1903. Watson Library Special Collections

In 1899 or 1890, Launder was hired as a finisher at Bradstreet's, a small fine bindery that was part of the larger reference-book publishing firm of the same name. The little bindery, located on Elm Street in Lower Manhattan, produced deluxe bindings for rare book and manuscript collectors, including J. Pierpont Morgan and Henry W. Poor. Two somewhat desperate letters exist from Launder to J. P. Morgan's librarian, Belle da Costa Greene, dating from 1914–15. These express Launder's concern over the death of Bradstreet's superintendent and the tentative future of the bindery. In the letters Launder emphasized the quality of the bindings Bradstreet's had bound for Morgan (including Thackeray's original manuscript for Vanity Fair), in the hope that she would find work for his shop. As Greene surely knew of Ivins's need for a binder and of Launder's need for work, it's possible that she later recommended him for the Museum's binding specialist position. The two fine bindings shown here illustrate Launder's masterful work during the Bradstreet's years.

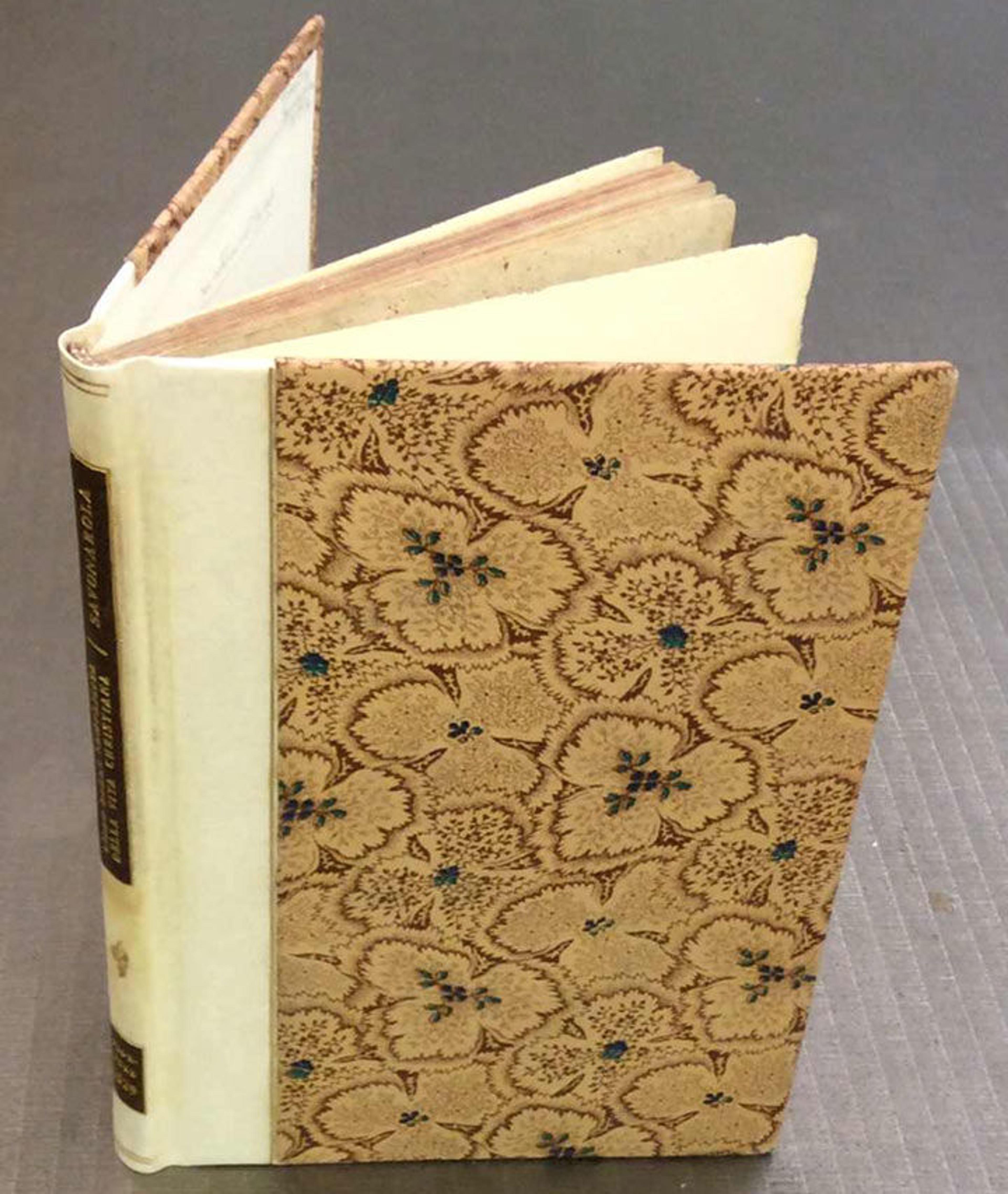

Alfred Launder bound hundreds of books for the Department of Prints in quarter or half vellum or natural linen, all with decorative side panels of cloth or paper. This example features his characteristic style of rebinding books with a vellum spine, lined printed cloth sides, colorful embroidered endbands, and gold-tooled leather labels. Savonarola. Della Simplicita della Vita Cristiana. Florence: Heirs of Filippo da Gunta, May 1529. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Harris Brisbane Dick Fund, 1925 (25.30.141)

Launder usually embroidered elaborate endbands, such as this one, on which he used four colors of silk. Launder's developed his unique endbanding technique to compensate for a skill usually performed by women and adapted for his "calloused, masculine fingers." You can read about his trials and tribulations in the development of this technique in chapter five of his manual. Abbé Prévost. History of Manon Lescaut and of the Chevalier de Grieux. London: George Routledge and Sons, 1886. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Harris Brisbane Dick Fund, 1917 (17.3.2641[5])

By 1929, when Launder began work at The Met, he was known as one of the best fine binders in New York City. He arrived at the Museum with extensive skills in the bookbinding arts, fresh eyes, an open mind, and a passion for the conservation of rare books. Launder's manuscript impresses upon readers his mission to educate collectors and binders about the responsible custodianship of rare books and the new technical principles to be applied to their repair.

There are so many interesting, amusing, useful, and emotional aspects of Launder's manual. I suggest that you read it for yourself if you are interested in hand bookbinding and conservation, although much of it would now be considered a historical document. Still, there are many timely practical instructions, and if it's at all possible that a bookbinding manual can be passionate and engaging, Launder's certainly is. He uses his practical treatise to share his professional history, technical challenges, and frustrations. He rants on the destructive traditional techniques practiced by his contemporaries and perpetuated by the trade, and offers instructions on how work should be undertaken in the best way, based on his experience at The Met.

This exposed spine, photographed from one of Launder's retired albums, shows his unusual strong, reinforced sewing technique, in which he sewed the book signatures through five linen tapes, using a butterfly locking stitch. You can read about Launder's sewing style in chapter two of his manual.

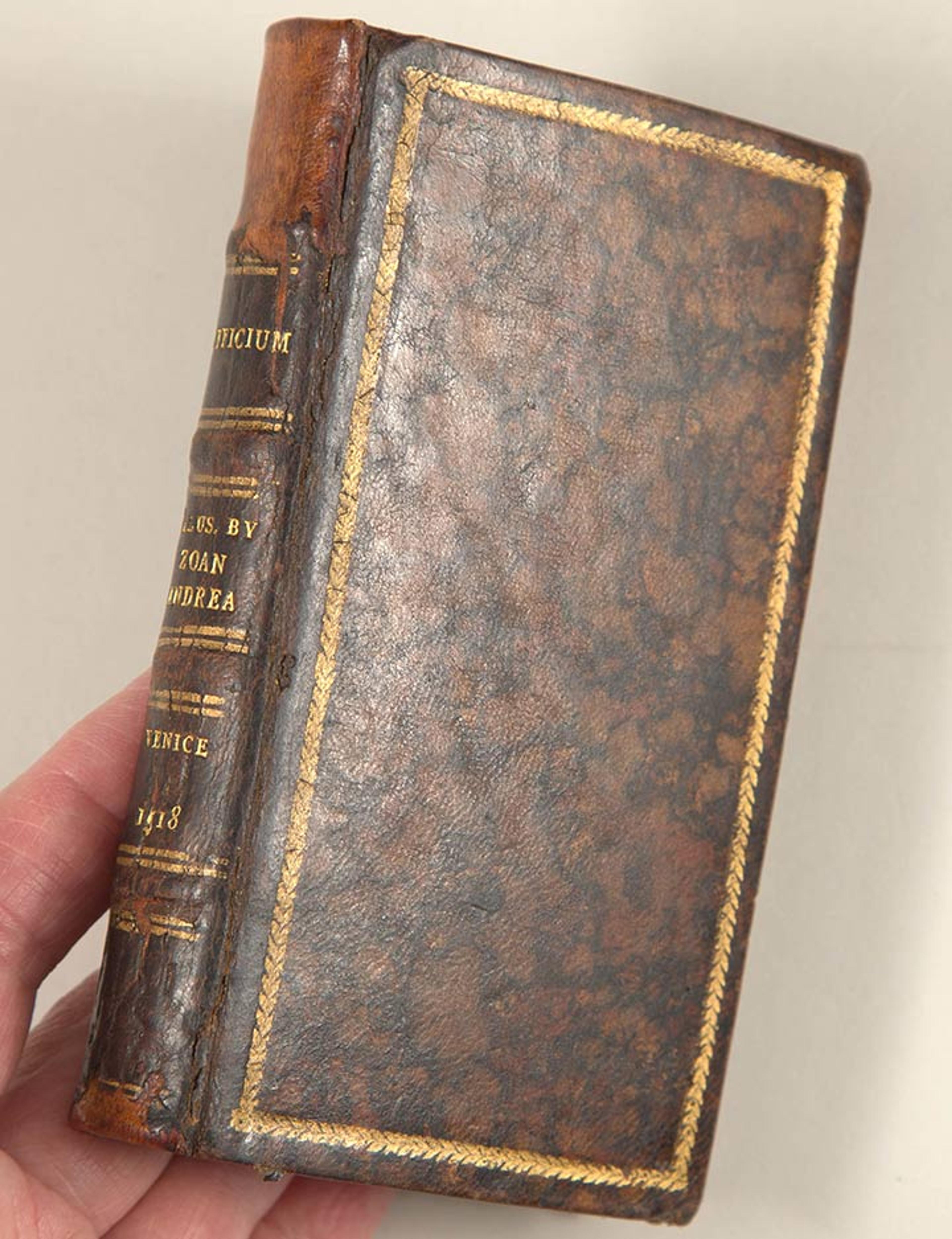

While Launder rebound many books in the Museum's collection, he also restored leather bindings. In this binding, the spine panels were damaged. It was repaired with leather and toned to match. Officiuz Hebdomade Sancte: Secundum Romana Curiam. Venice: Lucantonio da Giunta, 1518. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Harris Brisbane Dick Fund, 1923 (23.22.4)

Throughout Launder's time at the Museum, he made albums, new case bindings, boxes, and leather bindings, performed repairs on paper and bindings, and trained others. Many years before I knew anything of Alfred Launder or his written treatise, I was familiar with his bindings in our collection. His new bindings always stood out and are most unusual for several reasons: their binding style is a hybrid of fine and trade or commercial binding techniques; they are bound in high-quality, decorative materials; all of them feature delicately tooled flourishes and title labels; and they appear indestructible. All have withstood the test of time and, after more than 60 years of handling, I've never seen one that needed repair.

In 2000 Launder's manual was finally published for the first time (Guild of Book Workers Journal, Volume XXXVI, Number 1). I added a table of contents, an introduction, and photographs of Launder's books. While all of the information is there, many of Launder's dramatic punctuations and scratched-out text were removed by the editor. For this reason, among others, I think that binding enthusiasts would most enjoy reading the manual in its original form.

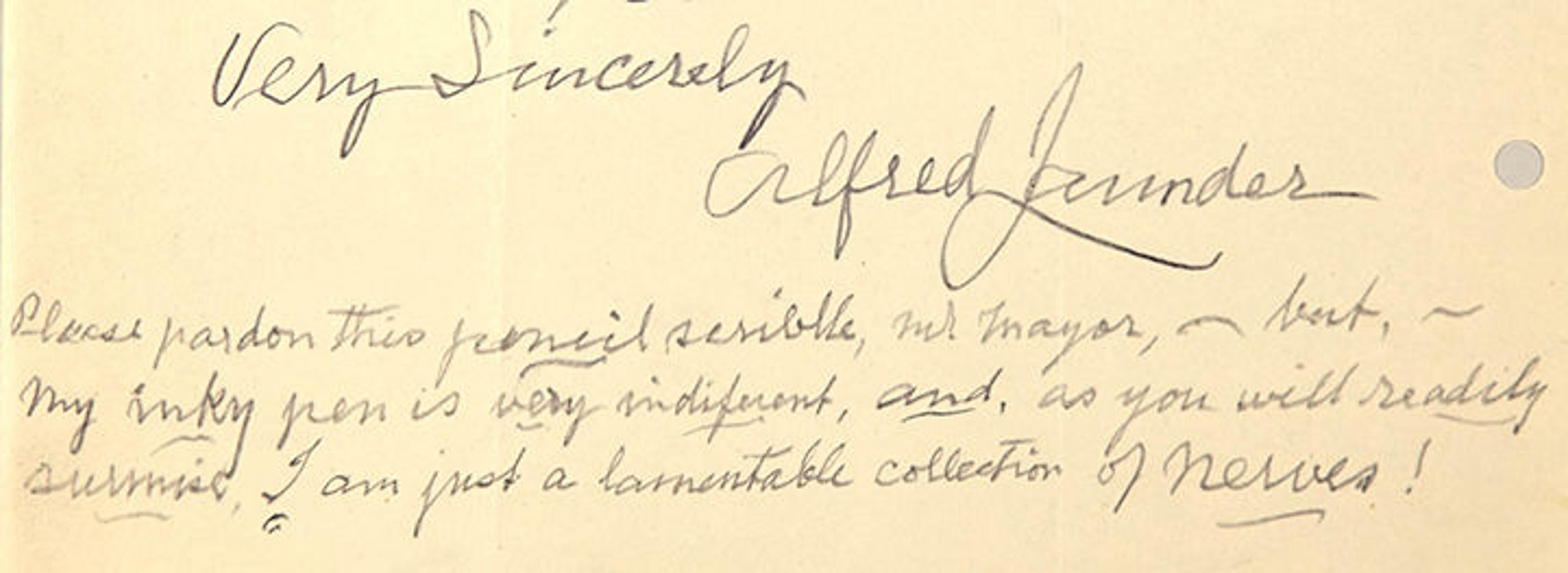

Detail from a two-page letter written in December 1948 by Alfred Launder accompanying the submission of his typescript manual to Museum curator A. Hyatt-Mayor. Watson Library Special Collections

I think about Alfred Launder every day while I'm working, and I'm grateful to have been able to study his work and bring his manual to public attention. I wish he could somehow know that the book conservation staff is following in his footsteps, working with passion to ensure the future of the Museum's books. If you would like to see Launder's books and learn more about him in person, this spring I will be giving two public talks for the Museum on Launder's work. I thank bookbinding enthusiasts Sophia Kramer, Jeff Stikeman, and Tom Conroy for their support in my ongoing research on Alfred Launder.

Related Event

Conversations with a Librarian—Alfred Launder, the Museum's First Bookbinder and Conservator

Friday, March 24, and Wednesday, May 3, 2017

The Met Fifth Avenue - Gallery 534 (Vélez Blanco Patio)

Free with Museum admission; though advance online registration is required.