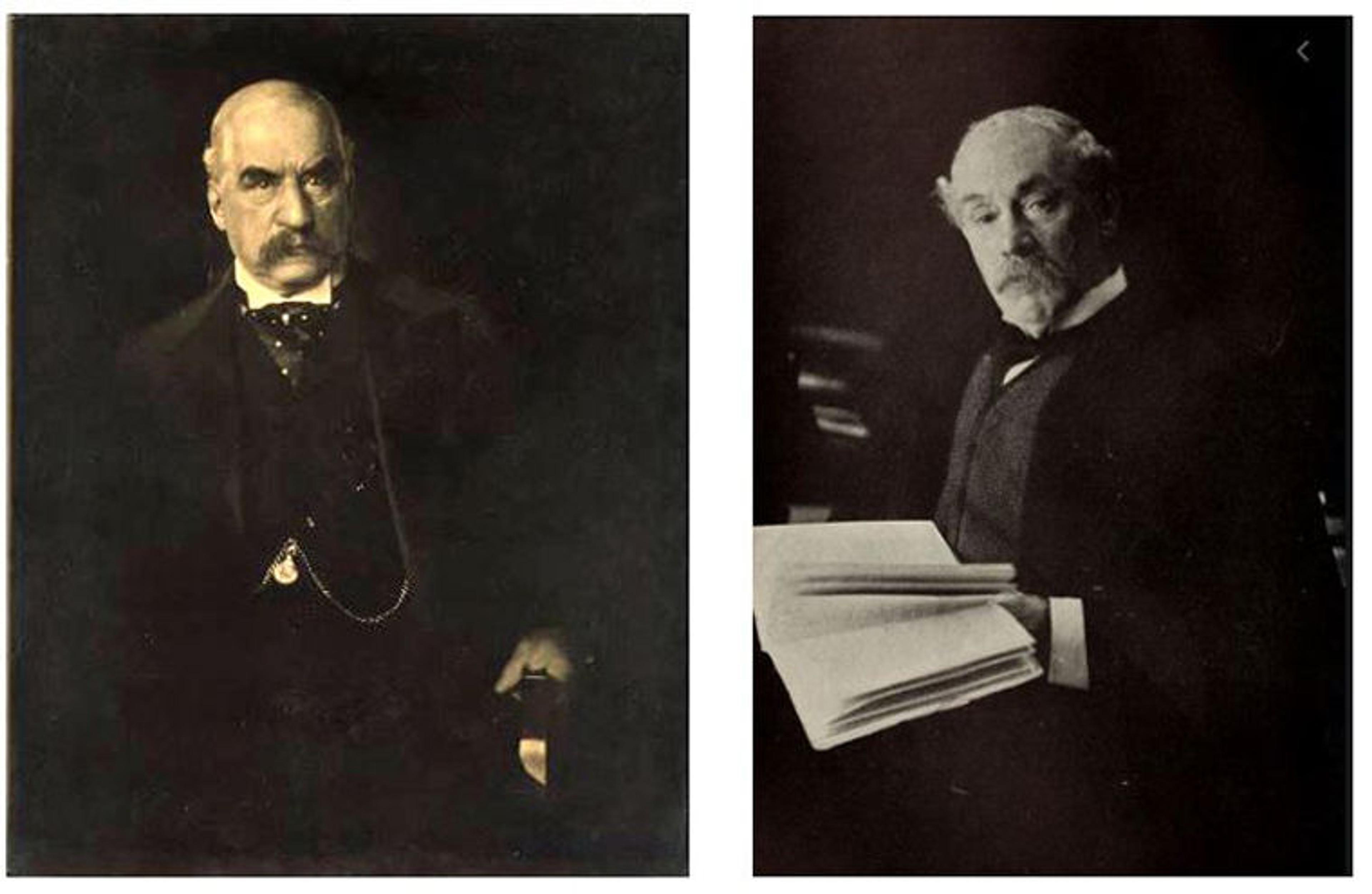

J. P. Morgan (1837–1913) and Caspar Purdon Clarke (1846–1911)

To read part one, click here.

General Luigi Palma di Cesnola, The Met's legendary first director, died in 1904. J. P. Morgan was appointed president in the fall of the same year. Morgan's first task was to fill the vacancy and identify a new director. It seemed only natural to recruit the director of the South Kensington Museum (now the Victoria and Albert Museum), which served in many ways as the model for The Met. Its director, Sir Casper Purden Clarke, was the most distinguished and certainly the most experienced museum director in the Anglo-American world. He knew about collection-building, exhibitions, and administration, and he knew about libraries. Beginning in 1855, the early reports of the South Kensington Museum show exceptional growth of the collections of both the museum and library. The number of readers reported in the early annual reports is striking. We can certainly concur with the observation made in the South Kensington report of 1869 that the intensive use of the library "proves decisively that the Art Library has met a want acknowledged by the public and students of Art." In 1906, Clarke shared his thoughts on The Met's library with the trustees:

The South Kensington Museum, in London, was forced in 1856 to start a library within its walls for reference works on Art and Education and although this Library was viewed with little favor by the government and even by the head administration of the Museum, the growth year by year was so rapid that before 1860 it became necessary to divide it into two divisions under separate heads, and now the National Art Library and the Science Library have become two of the largest and most complete specialist libraries in the world.

Clarke went on to invoke this as a model for The Met, saying:

In the building up of the collections of the Metropolitan Museum, the great work has to be done in a few years, and books will be amongst the most important tools used by us in achieving the result. I, therefore, propose that in dealing with the Library, the Committee should place no restriction upon the quantity of books purchased, or the space necessary to properly house them.

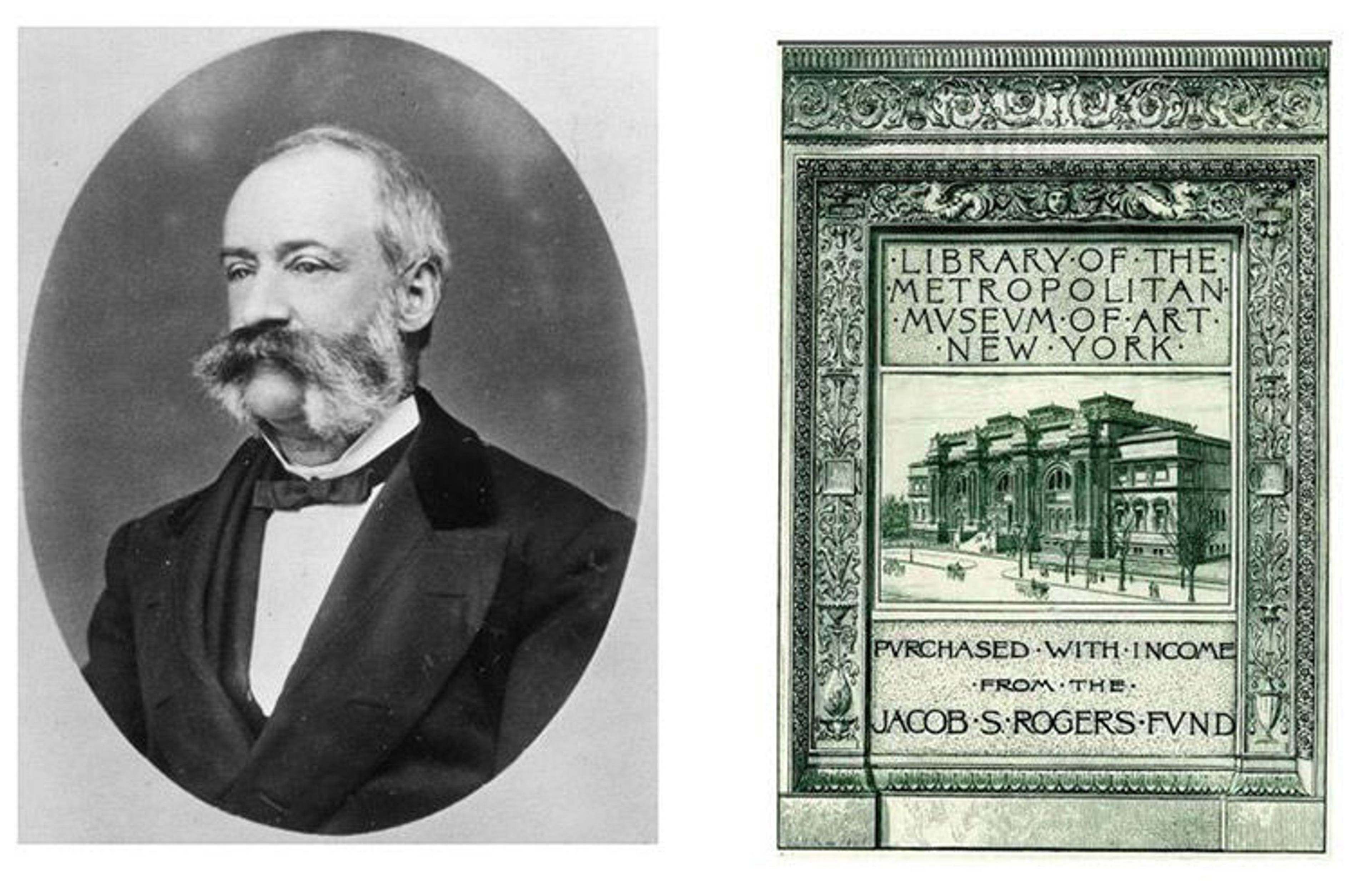

This may be the most passionate proclamation of institutional support for an art museum library in recorded history. The new director was confident, determined, and undeterred in his vision to build a library worthy of the highest ambitions of the Museum. He was in a fortunate position. The highly ambitious plans for The Met were beginning to take shape. In 1902, the new Fifth Avenue wing, designed by Richard Morris Hunt, opened to great acclaim. In the same year Jacob Rogers, a manufacturer of locomotives in Paterson, New Jersey, bequeathed an endowment to The Met of five million dollars "for purchase of rare and desirable art objects, and in the purchase of books for the Library of said Museum, and for such purposes exclusively." By 1904 the Museum had the Rogers Fund, a key fund for the library, which has been used for acquisitions ever since. The floodgates had opened and the library was receiving books, through purchase and gift, from throughout Europe and Japan. Important runs of the journals of antiquarian societies, excavation reports, auction sale catalogs, and monographs were arriving in a rich and steady stream.

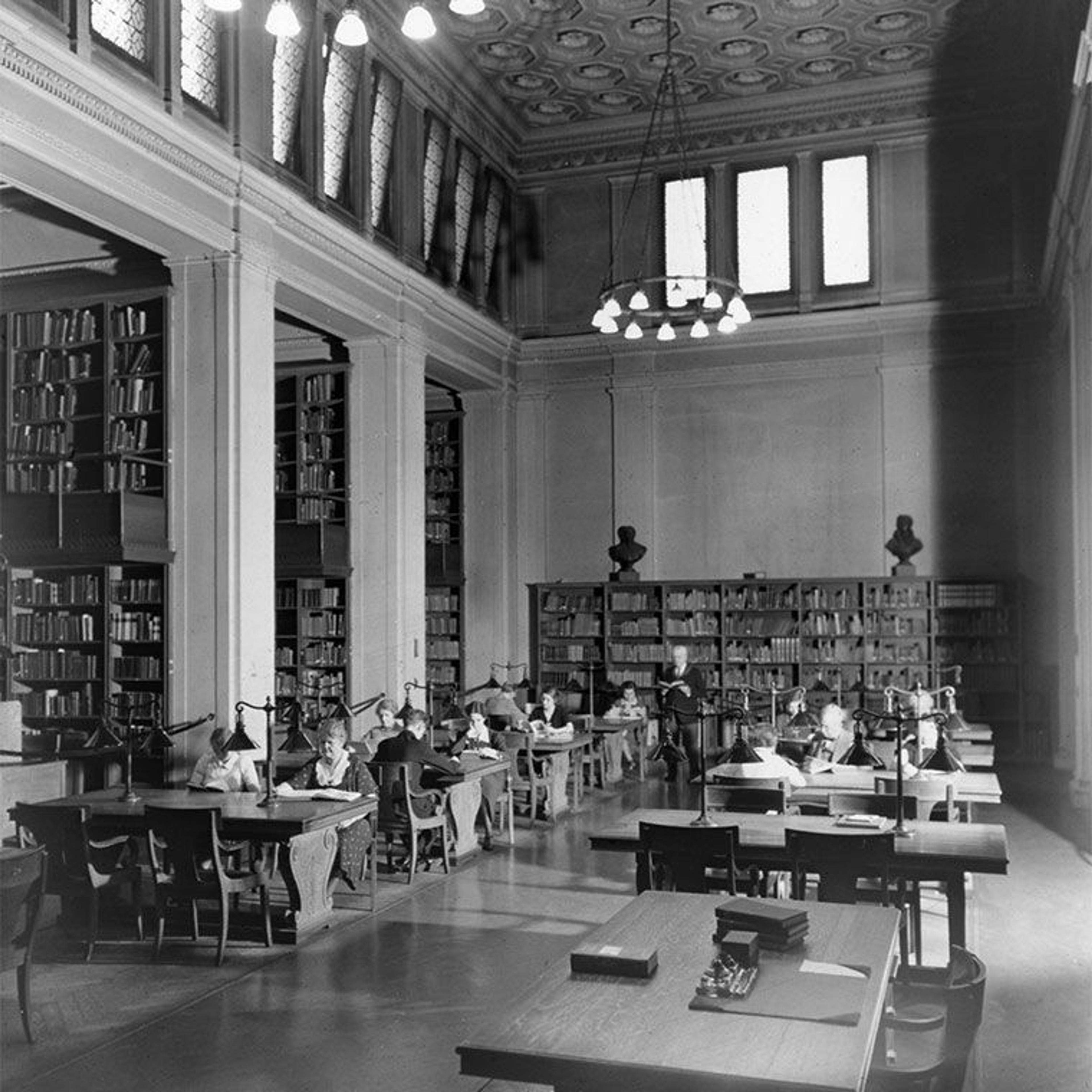

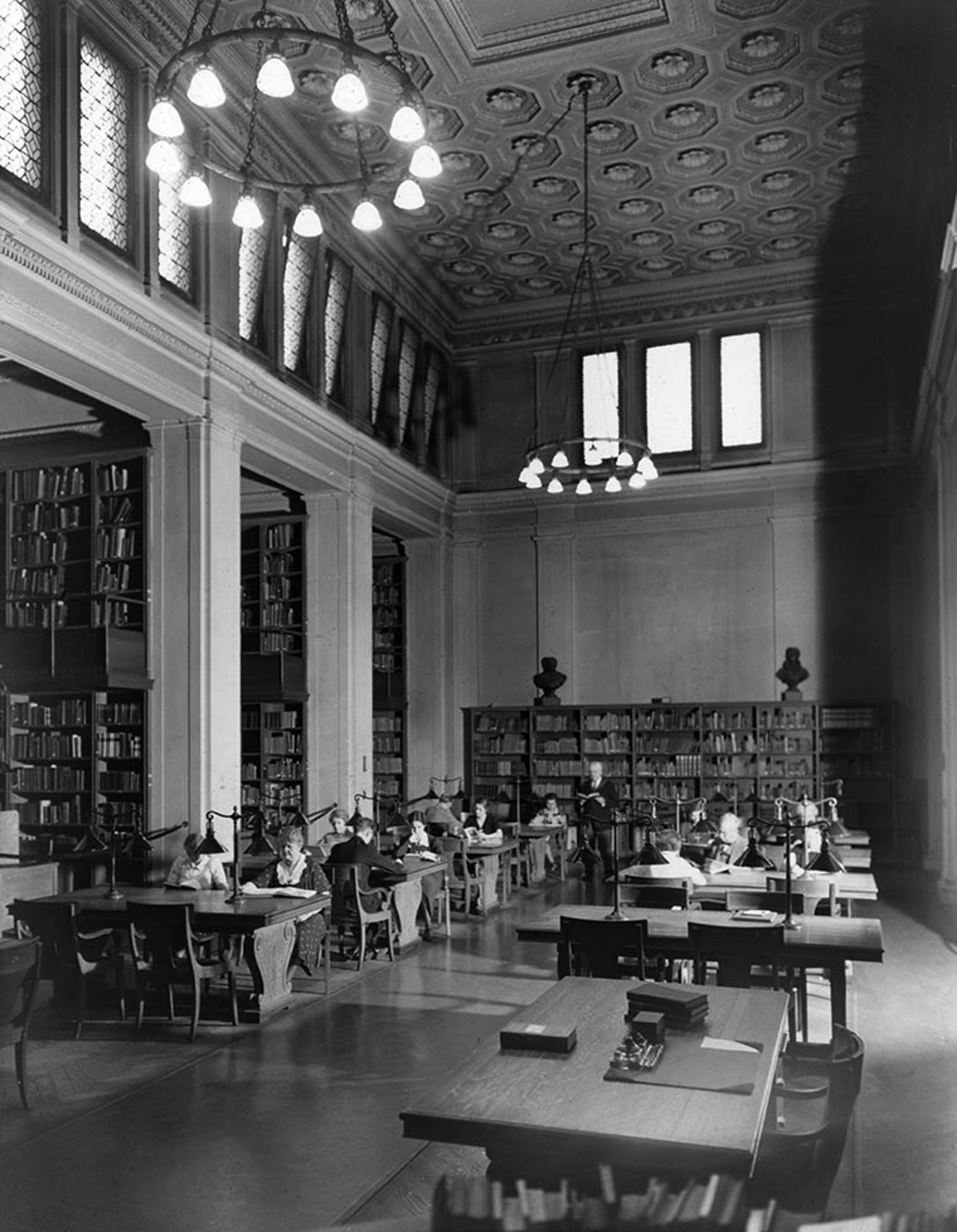

Jacob S. Rogers (1824-1901) and the Rogers Fund bookplate

Clarke's talk to the Trustees was preparing them for The Met's next major building project, a new library designed by the country's most important architects, McKim, Mead, and White. Plans were already in preparation for a new building to be erected on the south side of the Museum—just east of the Central Park entrance, the location of The Met's current Watson Library—which was built on the footprint of the old. The new library opened in July 1910. Unfortunately, Clarke, the library's great champion, was not present to celebrate his achievement. Bad health had kept him in Europe for more than a year, and Edward Robinson, who would succeed Clarke as director, performed his duties. The new library had capacity for 50,000 volumes, including 210 international journal subscriptions. From the very beginning, The Met's library was committed to serving the research needs of the staff and the public, and its design accommodated each group. Eight of the ten alcoves that housed books had tables and chairs designed by the architects for Met staff, while other readers made use of similar tables in the center of the room.

The new library just to the right of the northwestern view of the Weston Wing was completed in 1910.

Reading room of the new library, designed by McKim, Mead, and White

The report on the new library was written by William Clifford, who served as the librarian from 1905 to 1941. He closed his report by noting:

Although there has been a steady increase in the number of readers, it is hoped that members and others who are not yet familiar with the scope of the Library, will avail themselves of the opportunities it offers for the study of ancient and modern art. The library is open from 10 a.m. to 5 p.m. except on Sundays and holidays.

Nearly 110 years later, happily, we can say much the same. We continue to see a steady increase in the number of researchers, and have only slightly modified the schedule so that we are open until 5:15 p.m. on weekdays and 5 p.m. on Saturdays.

Forty years after the charter that expressed its purpose "of establishing and maintaining in said city a Museum and library of art," the library was in new building designed by the country's finest architects. The reading room was spacious, with ample room for staff, visitors and 50,000 volumes. The collection now exceeds one million with 650,000 on site and more than 350,000 easily retrievable from an offsite storage facility. The Rogers Fund remains instrumental for acquisitions, supplemented by additional endowments and important gifts to the collection, as well as the annual dues of the generous Friends of Watson Library. Additional blog posts will tell the next chapter in the story of The Met's incomparable library.

With thanks to Holly Phillips and Sophia Alexandrov for their invaluable assistance.

For more in this series on the history of The Met's libraries, click here.