An article delivered via interlibrary loan to a Met staff member, courtesy of the New York Public Library

The Metropolitan Museum of Art may have closed for five months at the start of the pandemic, but the research of its curators, collection managers, conservators, editors, research assistants, Volunteer Guides, and Fellows went on, despite the fact that their favorite library (Watson Library of course!) was also closed and remains closed to visitors to this day. The titles listed below are just a tiny sampling of the hundreds of journal articles and book chapters research staff at The Met have consulted with the help of Watson Library during this extended work from home era.

“The Lion, the Hare, and Lustreware”

“Cybernetic Guerrilla Warfare Revisited: From Klein Worms to Relational Circuits”

“The Discovery of the Unconscious in Ancient Egypt”

“The Gramophone: Recorded Music and the Cultivated Mind in Britain between the Wars”

“A model for time-temperature-mortality relationships for eggs of the webbing clothes moth exposed to cold”

But how? Contrary to popular belief, “everything” is not online, especially for free. Much of what our researchers need still exists only in print format. In the “Before Times,” they would request the books through our online catalog, and library staff would deliver them to their offices. Or, if the text was outside of the scope of The Met libraries’ collection, they would request books through interlibrary loan (“ILL”) and the books would be shipped from a library as nearby as Columbia University or as far away as the University of Melbourne. Museum staff needing pages from a book or journal not held by one of The Met’s libraries requested the pages through their ILL accounts and received them as PDFs within a few days. To give you a sense of scale, in 2019 we borrowed 1,858 books and received 1,091 scans for Museum staff via ILL. At the moment of closure on March 11, Museum staff had over 360 physical ILL books checked out to them, a few dozen were in transit, and about 175 were out on loan to other libraries.

A small batch of ILL books retrieved from the Museum’s loading dock after Watson Library staff were allowed back into the building on a very limited basis in July 2020. Photo by Amy Hamilton

In the “After Times,” nearly all lending of physical items has ceased. Even if one library could lend a book, the borrowing library wasn’t open to receive it. This was certainly the case for Watson Library, which had no staff onsite at all from March 12 until late July. According to OCLC, which manages the bulk of ILL transactions between US libraries (as well as dozens of international members), nearly 400,000 physical items were on loan to 5,674 libraries via its WorldShare ILL network when the pandemic hit the US. Needless to say, ILL librarians went into a collective panic contemplating the unknowable fate of all those books.

ILL became almost exclusively a “scan-and-deliver” service between libraries that had skeleton crews onsite and were willing to help out their desperate colleagues across the globe, and those that were completely closed. From March 12 to August 25, we relied almost exclusively on the generosity of other libraries to provide The Met staff with the materials they needed, even if it was something we owned (which in the Before Times was an absolute no-no for us!). Because it is not legal or practical to scan whole books or very long articles, research staff had to adjust to the new reality of being specific about what they needed from a book—to which I’m happy to say they adapted quickly.

Delivery receipt from an article provided by the Stadt- und Universitätsbibliothek in Zürich, Switzerland

We normally rely on a group of 120 or so research libraries in the US to fill the majority our ILL requests, but most of them were completely shuttered through the summer. Therefore, most of the scans we requested came from libraries with whom we had no prior relationships, including the Reformed Theological Seminary, Orlando Campus; the University of Macau; the Museum of New Zealand; the University of Alaska Anchorage; the National Agricultural Library; and many, many others. We are so grateful to all the libraries big and small who helped us through the summer and continue to help us during this period of intermittent and extended closures.

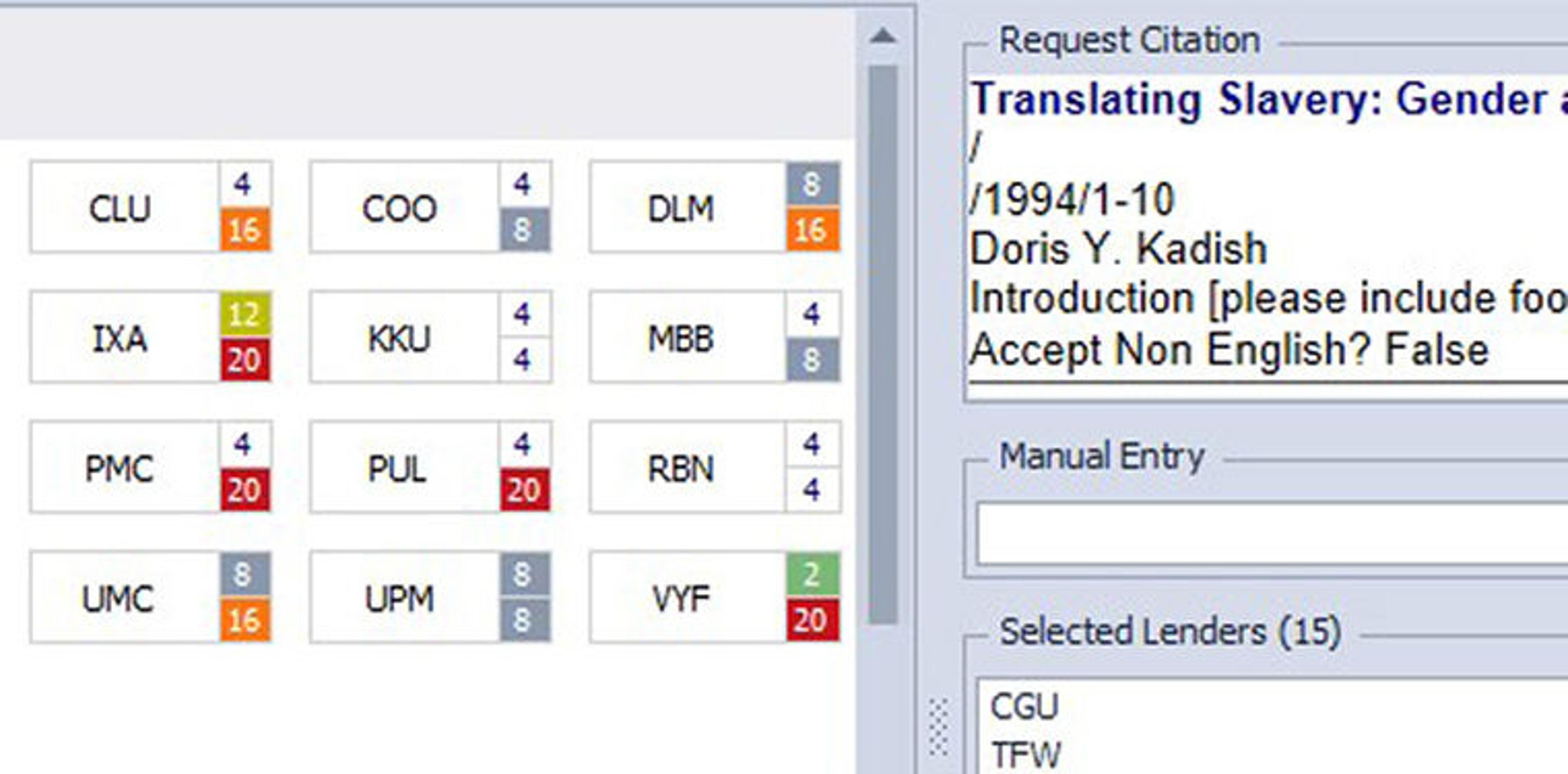

Worldshare ILL libraries have adopted an ad-hoc color coding system to indicate if they are open at all; if they provide scans only; or if they are lending physical books.

There are thousands of libraries in the Worldshare ILL network, though, and levels of service range widely. How can an ILL librarian tell who is doing what in order to fulfill requests as quickly as possible? Early on during the pandemic, over a series of twice-weekly conference calls that were part therapy and part strategy, a group of us suggested repurposing OCLC’s color coding system—which normally indicates how many days a library needs to fulfill scan and book requests respectively—to instead indicate their level of service. As much as anything can in the ILL universe, this took off like wildfire. In the example above, in which the three-letter symbols represent individual libraries, a clear or gray numbered box indicates full service, orange indicates the library has staff onsite to scan from the collection but is not lending physical books, and red indicates the library only provides scans from electronic resources. This is just one example of how the ILL community worked together to come up with ad-hoc solutions to unprecedented situations. To this day we still have weekly conference calls that are as productive as they are therapeutic.

Since late August, Watson Library has expanded the services we provide to The Met staff and our ILL partners. A few library staff are onsite scanning from books and journals located in select locations within the building. All of this is done through the ILL system, called ILLiad (librarian humor; wait till you hear about Odyssey!). We are also able to circulate a subset of our physical books. More about these services are in this blog post by my colleague Amy Hamilton.

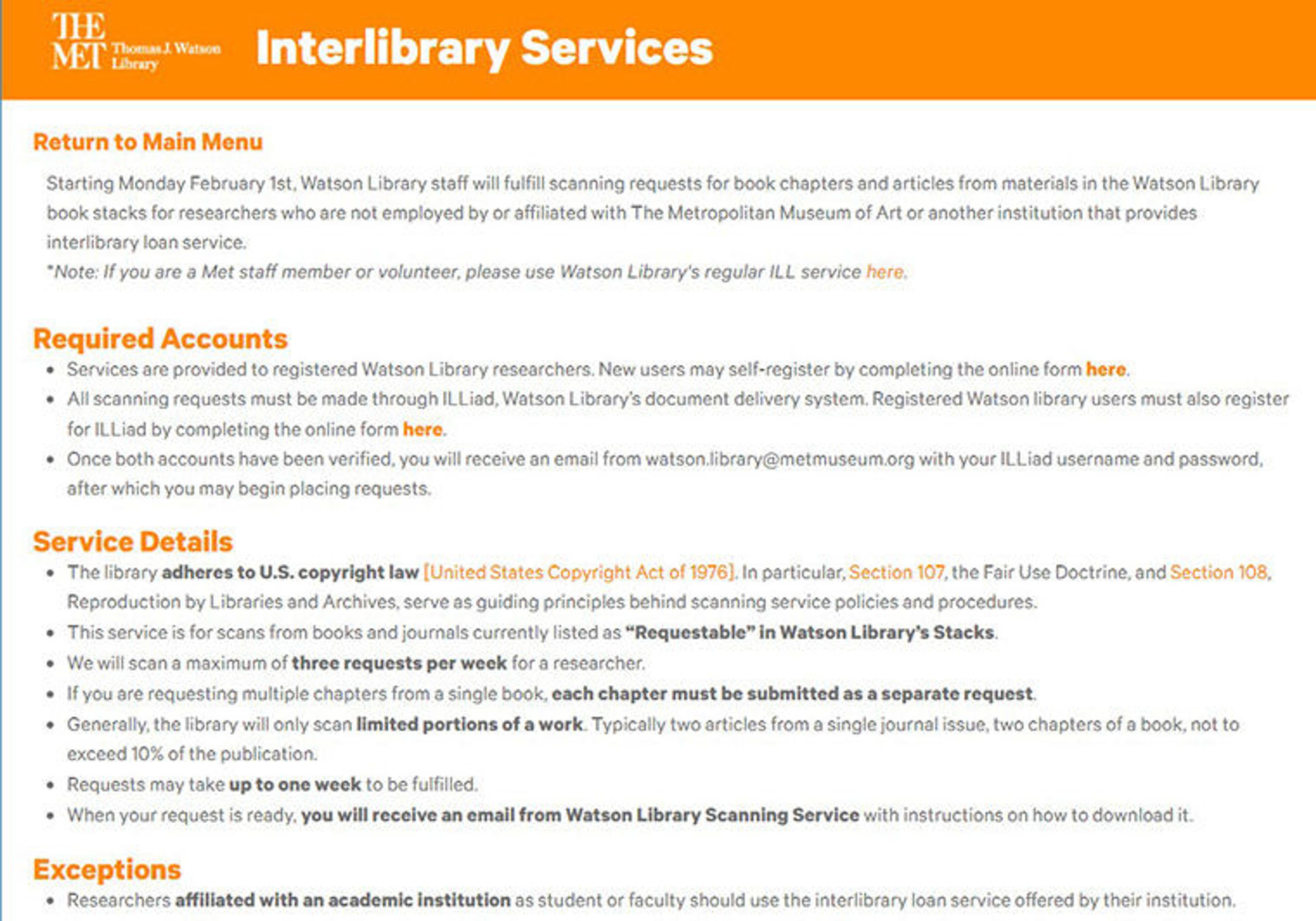

We have recently expanded our scanning service to independent researchers.

Most recently, we have expanded our scanning service to researchers who do not have access to ILL through their college, university, or local public library. Not without incident but ultimately with success, we built out a separate set of web forms for them to use that feed directly into ILLiad as well.

Since March 2020, we have fulfilled 2,450 scan requests for Met staff through their ILL accounts—about 1,680 from libraries across the globe and another 770 from our own collection. We’ve also provided nearly 700 scans to other libraries. And while it’s still a fledgling service, as of March 1 we have provided over one hundred twenty scans to independent researchers.

And lest I leave you hanging, many of those 400,000 books out on ILL when the pandemic started have made their way back to their homes. It is no small miracle that The Met staff have returned all of the over 360 ILL books they had checked out to them, considering how dispersed we have been! And fewer than twenty of the books we lent to other libraries have yet to make their way back. We are confident we will see them all again soon.

What one year ago was just “interlibrary loan” (the sending of books and articles between libraries) has now become a fully integrated scanning service for staff at The Met, our ILL partners, and even independent researchers. We are very much looking forward to circulating physical books again when things get back to “normal,” but I am quite certain (in a mostly good way) that “normal” is not a thing anymore and that ILL and document delivery have forever changed.