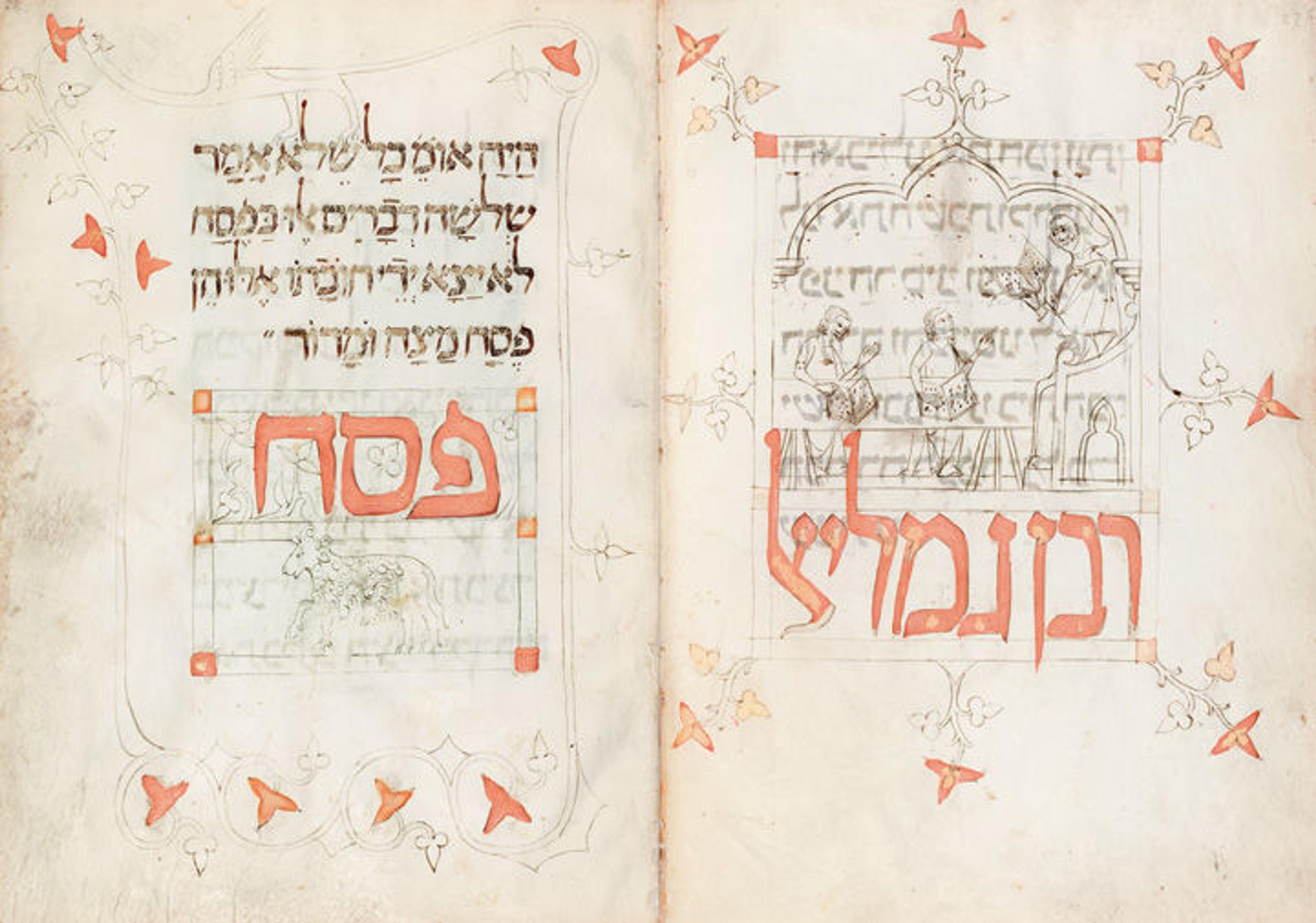

Hallel (fol. 33r), from the Prato Haggadah, ca. 1300. Tempera, gold, and ink on parchment. Spanish. Courtesy of The Library of The Jewish Theological Seminary, New York

«The Haggadah lucidly outlines the text for the Seder, the festive meal celebrating the Jewish holiday of Passover, and traces the biblical story of the Exodus, commemorating the Jews' miraculous escape from slavery in Egypt. The Prato Haggadah, however, currently on view at The Met Cloisters, is something of a puzzle. Within its covers are pages in various stages of finish, from folios that bear only the Hebrew text to those that are fully illuminated in gold and vibrant colors. »

Why work on the book was halted is a mystery, yet its unfinished state answers many questions about the production process of medieval illuminated manuscripts. Initial underdrawings, usually buried under layers of polychrome tempera, are laid bare to the naked eye, as are the early stages of preparation for gold leaf accents.

Two of the unfinished folios in the Prato Haggadah. Paschal lamb (fol. 28r) (left) and Rabban Gamaliel teaching students (fol. 27v) (right), from the Prato Haggadah, ca. 1300. Spanish. Courtesy of The Library of The Jewish Theological Seminary, New York

One of its gloriously completed pages, folio 33r, shown above, illuminates the beginning of Hallel, the joyous prayer of praise and thanks to God (Psalms 113–118) that is sung at the conclusion of the Passover meal. Hallel is recited on a number of holidays throughout the Jewish calendrical year, including the upcoming Sukkot (the Feast of Tabernacles, celebrated from Tishrei 15 to 23, corresponding this year to the evening of October 16 through October 25).

While Passover commemorates the Exodus, Sukkot commemorates God's divine protection of the Israelites in the desert after their departure from Egypt, memorialized in the observance of taking one's meals out of doors in a sukkah, or temporary hut. Passover and Sukkot are further linked by being two of the three yearly Pilgrimage Festivals for which Jews in ancient times traveled from all corners of the world to Jerusalem to partake in services and present offerings in the Temple.

Unlike medieval Christian manuscripts, which often begin prayers with a single, elaborately decorated letter, Hebrew manuscripts adorn the entire first word, as there are no capital letters in Hebrew. Here, illuminated in gold and embellished in bright colors, is the exclamation "Hallelujah!" Framing the text are illuminations that complement the jubilant nature of the prayer. White heightening is used to create lively patterns in the borders and delicate dimension within the letters themselves. Spritely foliage sprouts at every turn while birds add their calls to the song. Humorous hybrid creatures abound, and the ascenders of the two lameds of "Hallelujah" face off in a show of futile ferocity, forever locked in positions too far apart to do more than stick out their tongues at each other. The illuminator used the wide blank space of the page to his advantage, taking liberties and reveling in the joyousness of the text. The gold, vibrant colors and lighthearted imagery add to the sense of jubilation with which the reader praises God, whose glory extended "from the rising of the sun to its setting." Although written for Passover, this text and its exuberant illuminations are a timely celebration of Sukkot and of thanksgiving in general.

In honor of Sukkot, we encourage you to visit the Prato Haggadah at The Met Cloisters and welcome you to make your own pilgrimage to Jerusalem via the magnificent exhibition Jerusalem 1000–1400: Every People Under Heaven at The Met Fifth Avenue!