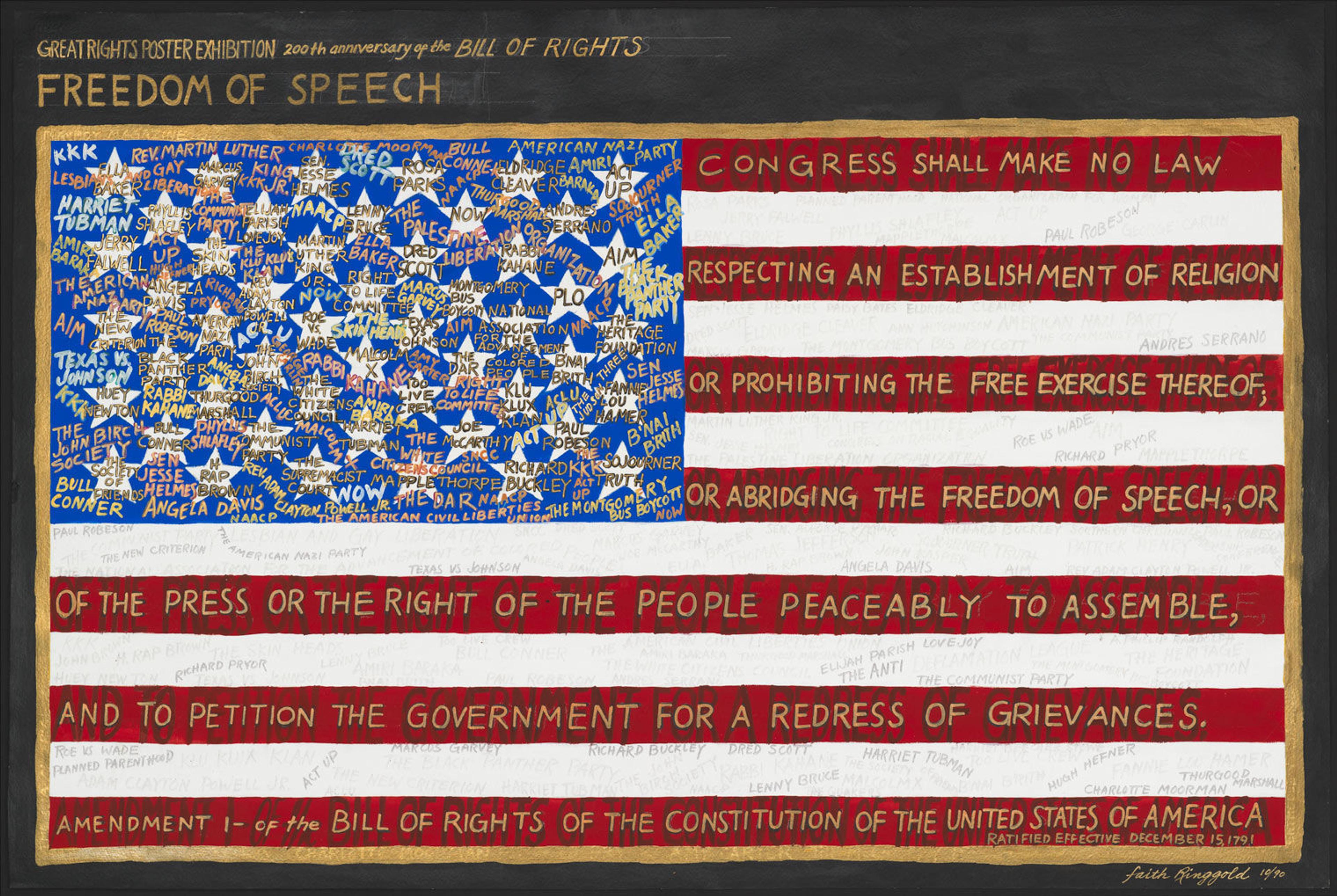

In her artwork Freedom of Speech, which is part of The Met collection, artist Faith Ringgold reflects on the history of the freedom of expression in the United States

A visit to The Met's sweeping halls, towering temples, and sunlit courtyards can offer an escape from our everyday realities. Yet some works of art in the collection draw attention to the very social issues that affect people's daily lives. Here we highlight two artworks by Faith Ringgold and Wendy Red Star that speak out against the mistreatment of cultures and communities. Both artists found a passion for art as kids and grew up to create artwork that considers how we make our world a freer and safer place.

Faith Ringgold (American, 1930). Freedom of Speech, 1990. Acrylic and graphite on paper, 24 x 35 3/4 in. (61.0 x 90.8 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase Gift of Hyman N. Glickstein, by exchange, 2001 (2001.288)

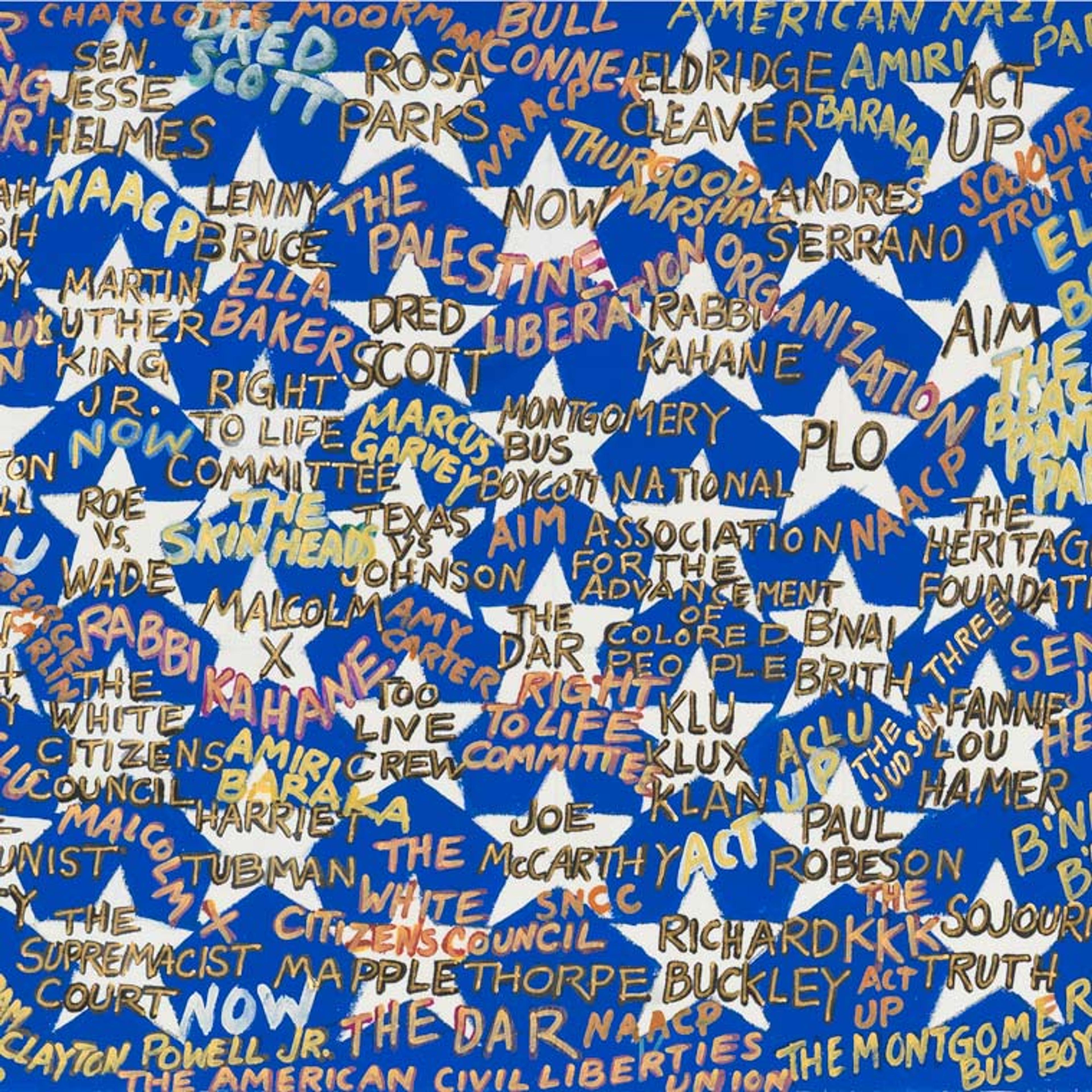

In the sixties, Faith Ringgold began to use written words and sentences in her art to make statements about the racism and sexism experienced in America by Black women like her. Ringgold's work reflects how Civil Rights activists at that time rallied support through posters, letters, and speeches. Thirty years later, Ringgold created her artwork Freedom of Speech, and its golden block letters still demand our attention. In Freedom of Speech, Ringgold painted an American flag and copied out the First Amendment onto the red stripes. The amendment says that all people should have the freedom to express themselves through religion, speech, or assembly, which means meeting in big groups. If you look closely, you can see that in the white stripes and stars, Faith packed in the names of people and communities who weren't safe to express themselves freely, even though the Constitution promised to protect them.

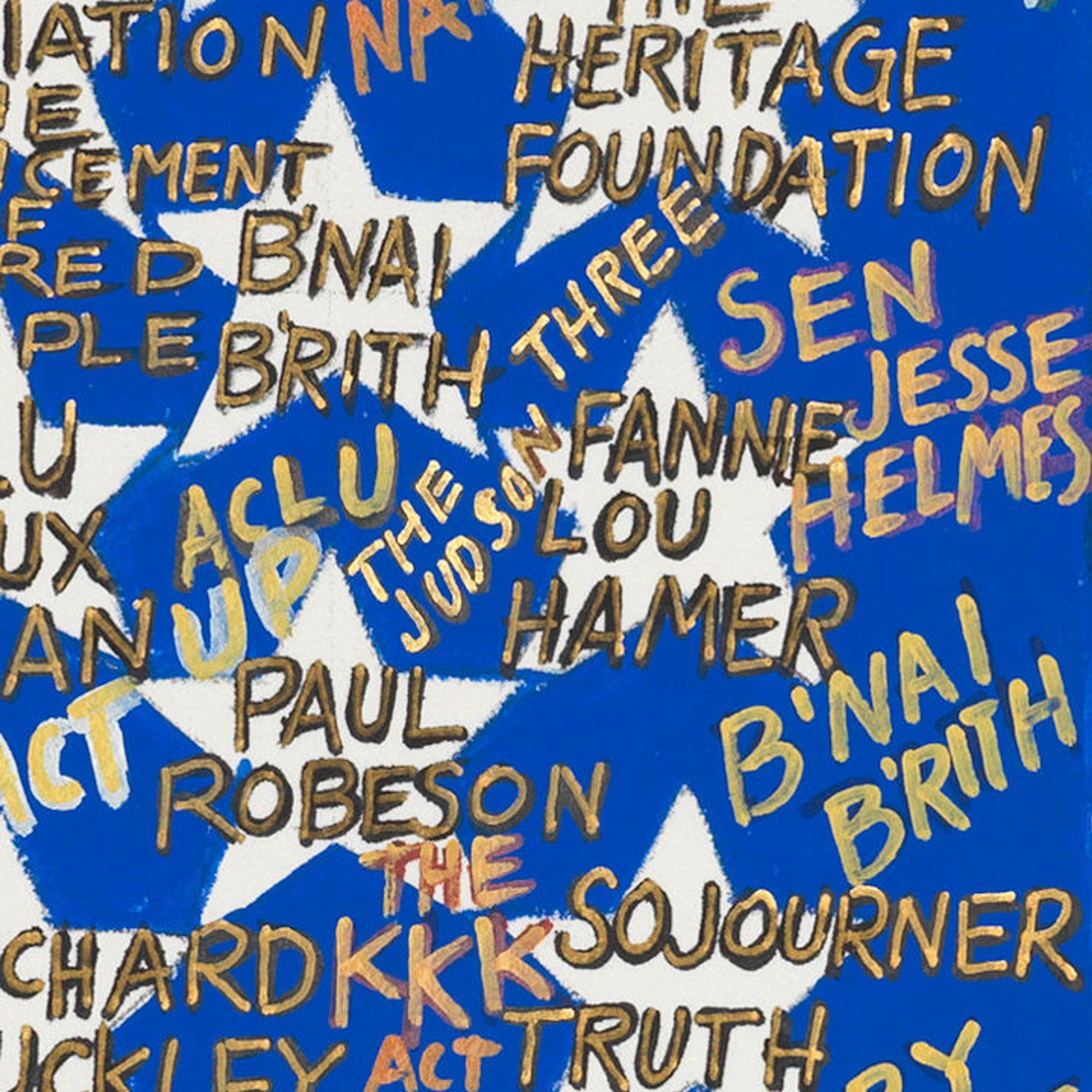

On the 39th star, for example, Ringgold wrote the name Fannie Lou Hamer, who was a moving public speaker and singer. During the sixties, Hamer organized voters in her community, especially Black working-class women like herself. Although Hamer and other activists were bullied, beaten, and jailed for training and registering Black people to vote, Hamer still went on to create the Mississippi Freedom Party, an organization that fought for Black voting rights and leadership in the state government.

Ringgold may have chosen the American flag as a background because of its power as a symbol, which means it connects to larger ideas. On the surface, the American flag can be a symbol of freedom and pride. Yet the meaning of freedom changes for people who understand that it is not guaranteed. For Fannie Lou Hamer, being a Black woman in America meant she was not treated fairly, and so the flag might have also reminded her of pain and struggle. When Ringgold includes Hamer's name on her painting of the flag, she honors her as someone who spent her life fighting for equal rights. Many other names crowd the flag in Ringgold's artwork, written in gold. Like Hamer, these people and their actions suggest deeper stories about the meaning and cost of freedom in America.

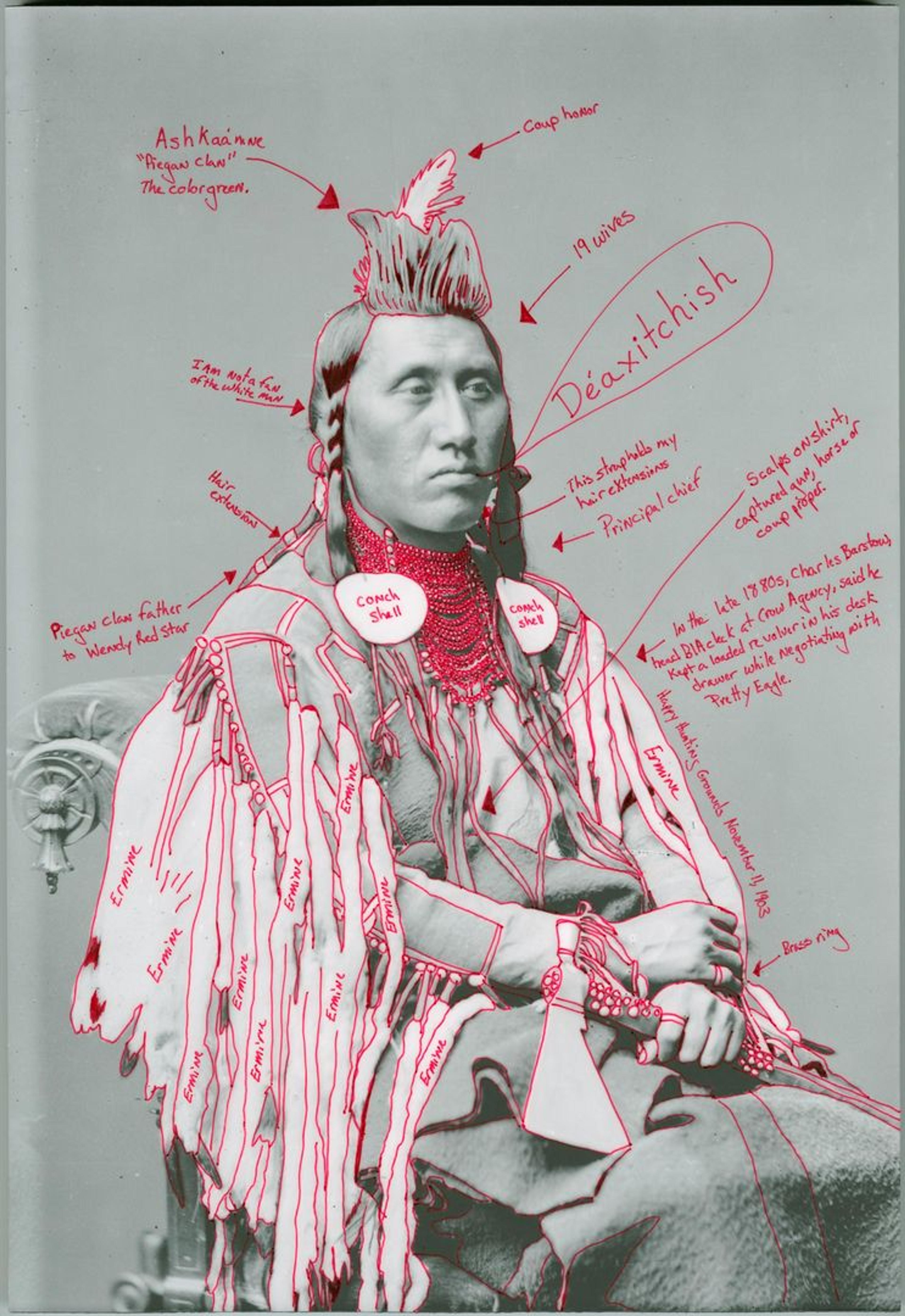

Wendy Red Star (Native American, Apsáalooke/Crow, 1981). Déaxitchish / Pretty Eagle, 2014. Inkjet print of artist-manipulated digitally reproduced photograph, 24 x 16 1/4 in. (61 x 41.8 cm) with additional 1" border. Image courtesy of the artist

Just like Faith Ringgold, Wendy Red Star writes messages in her artwork that remind us to treat all people fairly. To create the artwork above, Red Star started with a copy of a historic photograph: an actual portrait of Chief Déaxitchish, whose name means ''Pretty Eagle'' in the language of his people (the language Apsáalooke, also known as Crow).

Red Star researched the chief's story and found out he played an important role in American history. When the U.S. government wanted to build the Northern Pacific Railroad in 1880, it pressured Crow peoples to move off their lands. Pretty Eagle traveled with other chiefs to Washington, D.C. and met with President Rutherford B. Hayes to fight for their peoples' right to keep their homes. That's when the white photographer Charles Bell snapped the photo.

At that time, many white Americans didn't know much about Native peoples firsthand, and often formed opinions based on books they read, ideas they heard, or photographs they saw. They created dangerous pictures of Native peoples in their imaginations and believed that Native peoples were less intelligent, or all part of a single culture. As a result, when white artists took pictures of Native peoples, they didn't always present them as individuals with unique experiences. For example, Charles Bell often left out the names of the people he photographed, or incorrectly labeled them as belonging to the wrong nation.

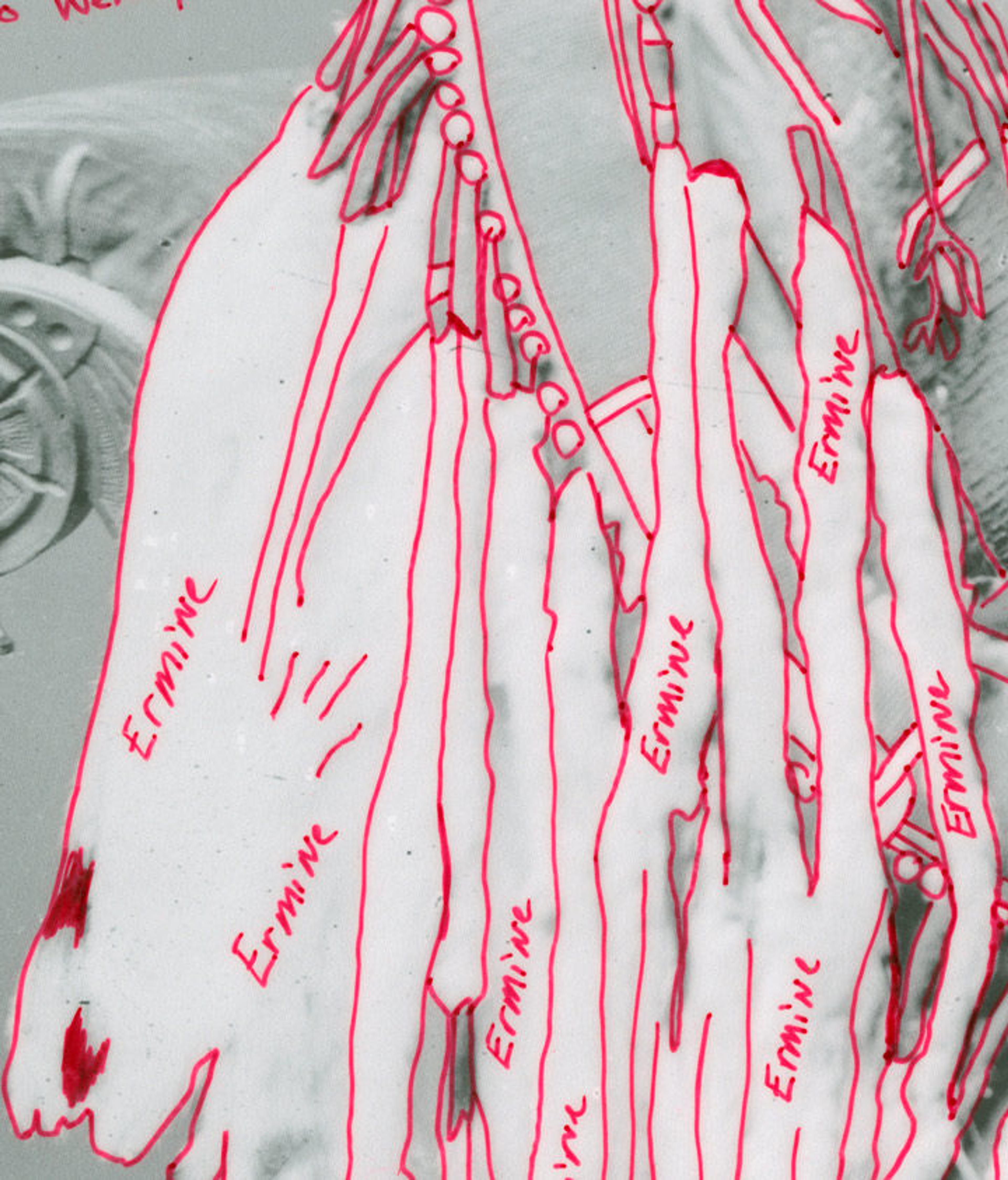

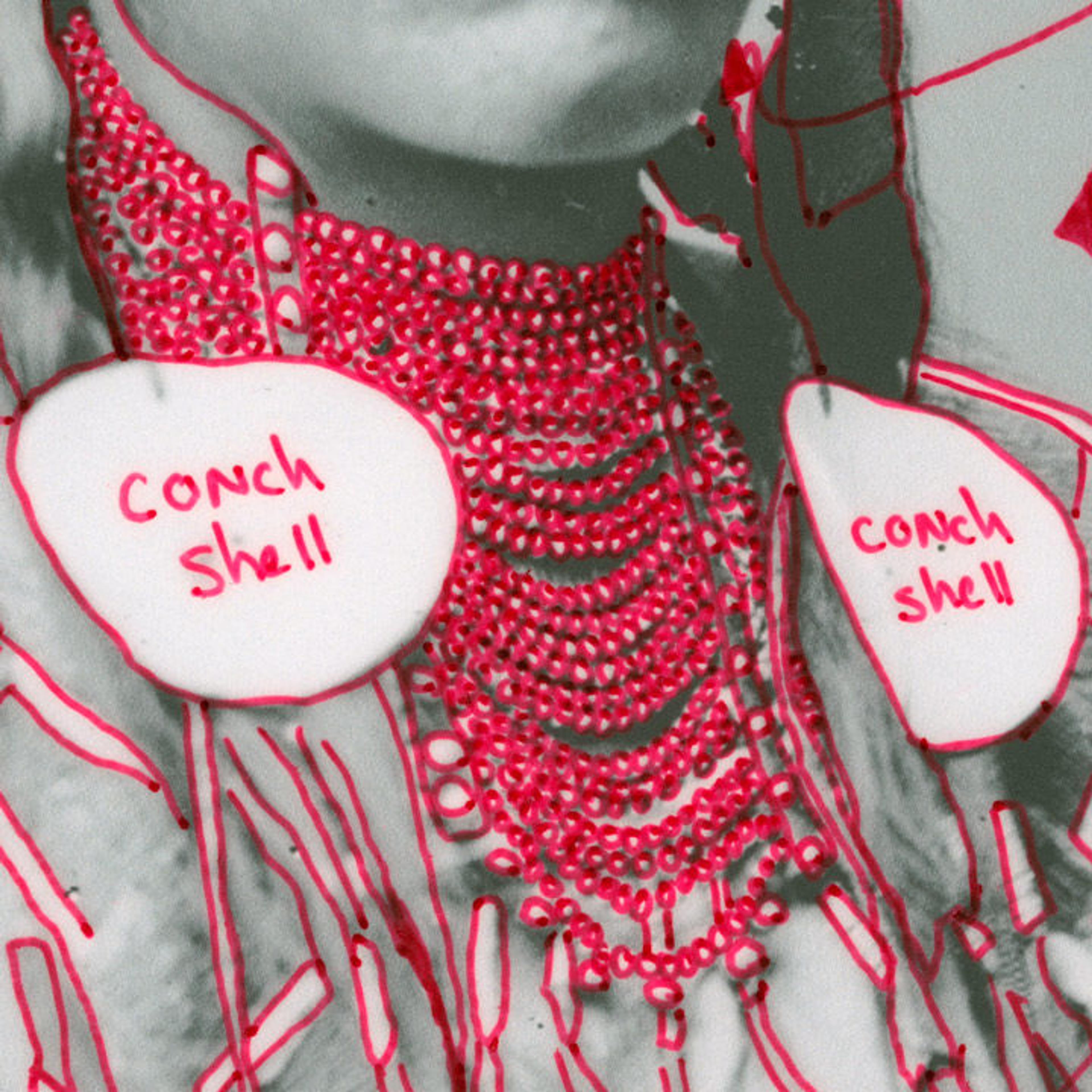

By creating their own images and speaking up about who they are, Native peoples have resisted the false information that surrounds their communities. When Red Star saw this photograph of the chief, she wanted to bring out his personal story and details about Crow culture and history. Like Chief Pretty Eagle, Red Star is from the Apsáalooke or Crow nation and grew up in Montana. Red Star knew that the clothing Pretty Eagle wears in the photo reveals important details about the life of the stately man who looks out at us with dark, steady eyes. To highlight his special clothes and jewelry, she made notes on the photograph in bright red ink.

Left: Red Star points out the ermine fur on Pretty Eagle's clothes

Right: Ermine fur on a Crow war shirt from the same time in history

War shirt. Made in Montana, United States, ca. 1880. Crow, Native American. Native-tanned leather, glass beads, pigment, wool cloth, ermine, human hair, and feathers, 41 x 59 7/8 in. (104.1 x 152.1 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, The Charles and Valerie Diker Collection of Native American Art, Gift of Valerie-Charles Diker Fund, 2017 (2017.718.6)

On the long white strips that hang from Pretty Eagle's sleeve, Red Star writes ''ermine'' to identify what they're made of and how important they were to him in his moment in history. The fur from ermine—a particular kind of weasel that turns white in the winter—is a symbol of power and bravery for Crow people. Think of Pretty Eagle wearing ermine to his meetings with the US President: not only did his presence and words command attention, but his clothing also told stories of the brave actions he took to become chief and the respect he had earned back home. Even though the six Crow chiefs had to travel over a thousand miles by wagon train and through snow to D.C., they wore their best clothes to show their pride in where they came from.

I can't stop looking at Chief Pretty Eagle's necklace. Can you imagine the time Red Star took to trace each tiny bead in red ink? Maybe she was imagining the person who made that necklace by hand. When she was a girl, she herself used to watch her grandmother design beaded jewelry and sew clothing on a sewing machine. When she grew up, Red Star sewed traditional outfits as works of art that connect to the creations of Crow women who came before her.

The power of the words in Red Star's artwork might remind you of the names Faith Ringgold included in her painting of the American flag. Like Red Star, Ringgold makes art that draws inspiration from the people around her. Born in 1930 in Harlem, New York City, Ringgold often stayed home as a girl to recover from asthma, but her mother gave her books to read, colored pencils for drawing, and fabric scraps to piece together. From her window high on Sugar Hill, Ringgold could see past the oak trees of Central Harlem all the way to the Empire State Building. On nights when she didn't want to go to bed, she stayed up listening to the women in her family talk about their lives. As an adult, she stitched visions of the neighborhood into quilts and created storybooks inspired by her relatives' words. Remembering their voices, she found her own.

Your Turn!

Faith Ringgold and Wendy Red Star make written messages part of their artwork to speak up about situations they believe are unfair. Are there things you'd like to speak up about? Find an image from the news, your family photo album, or the Internet. With strokes of paint, or pen and pencil, you can write and draw over the image to convey your own ideas.

Visit #MetKids, a digital feature made for, with, and by kids! Discover fun facts about works of art, hop in our time machine, watch behind-the-scenes videos, and get ideas for your own creative projects.