Fig. 1. Stag mask, late 19th or early 20th century. Tibet. Papier-mâché, polychrome, gilding, leather, and silk. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Mrs. Edward A. Nis, 1934 (34.80.3i)

«The exhibition Sacred Traditions of the Himalayas, opening tomorrow, explores Buddhist devotional practices across the vast Himalayan region from the thirteenth through the early twentieth century. These practices included ceremonial dance and musical performance, both important dimensions of Buddhist ritual that unified this vast region, which includes Nepal, Tibet, Bhutan, and Mongolia.»

At the broadest level, these public rituals were meant to insure abundance, prosperity, and protection from evil forces, but at the same time, the underlying narrative was an effective way of conveying subtle aspects of the Buddhist philosophical tradition to large audiences. The stag mask above (Fig. 1) is theatrically presented, with large eyes and tall antlers, in an effort to give the dancer stature and make the figure visible from afar. Stag dances occurred in a variety of contexts, but the most important one was publicly performed during the Gu Tor festival at the end of the year. After dancers embodying fierce deities banished malignant forces into a torma offering standing at the center of the ritual, a young monk dancing in a wrathful stag costume would cut the torma offerings into pieces, scattering them to rid the coming year of negative forces.

Fig. 2. Leaf‑shaped box with Vishnu, 17th–19th century. Top decoration: Newari; box: Tibet, Lhasa area. Gold, diamonds, topaz, emeralds, rubies, sapphire, pearl aquamarine, lapis lazuli and turquoise. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, John Stewart Kennedy Fund, 1915 (15.95.167)

Artwork was another central focus for the diverse religious communities of the Himalayas. Within the Himalayan conception, the gods resided in dazzling jeweled palaces in heavens and pure lands, an idea that can be traced back to the earliest Buddhist traditions in India, where such crystalline structures are described in texts and depicted in sculpture. This is perfectly expressed on the lid of a golden box that uses shaped aquamarine to represent the Hindu god Vishnu (Fig. 2). He is flanked by attending figures made of lapis lazuli that boldly stand against delicate gold filigree within a field of large emeralds, diamonds, sapphires, rubies, freshwater pearls, and turquoise. Devotion to the Hindu gods Vishnu and Durga dominated the local Newari tradition in Nepal, where the box's lid was crafted. From the seventeenth through the nineteenth century, these workshops also produced much of the high-quality jewelry found in the Tibetan Buddhist context.

Fig. 3. Forehead ornament for a deity, 17th–19th century. Newari for Nepal or Tibet market. Gold, diamonds, rubies, emeralds, sapphires, lapis lazuli, coral, shell and turquoise. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, John Stewart Kennedy Fund, 1915 (15.95.161)

When visiting a temple, especially on pilgrimage, it was meritorious to take off one's jewelry and give it to the Buddha and to the monastic order as an act of devotion (dana). For this reason, personal jewelry came to be integrated into religious imagery. This practice of giving was probably also the source for the many precious stones reworked into large-scale jeweled objects destined to embellish images of the gods such as this forehead ornament (Fig. 3).

Here, the four Tathagata Buddhas, deities that each preside over a pure land in one of the cardinal directions, are presented. These Buddhas frame a double-pronged vajra done in lapis lazuli with a diamond at its center. Conceptually, this represents the vertical axis of the universe, linking the unshakable vajrasana throne, where the Buddha reached enlightenment under the Bodhi tree, to the heavenly realms of the Tathagata Buddhas. Like a bolt of lightning, the vajra at the enlightened center of the universe is a perfect expression of the diamond vehicle of Buddhism or Vajrayana.

Fig. 4. Vajrabhairava with his consort Vajravetali, 18th–19th century. Mongolia. Tung-oil stucco, wood, gold, cinnabar, and other pigments. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Bequest of Kate Read Blacque, in memory of her husband, Valentine Alexander Blacque, by exchange, 1948 (48.30.14)

The veneration of images was central to Buddhist practice, and the donation of sculptures was a way the lay community could generate great spiritual merit and insure a positive rebirth (Fig. 4). This ferocious image of Vajrabhairava from the Zanabazar tradition of Mongolia is a wonderful example of a sculpture likely donated by a pious individual. This elaborate and intricate piece was fabricated from a silt substrate bonded using tung oil over a wire armature. It was then gilded using pure gold and painted in an effort to simulate a metal sculpture. It seems clear that the donor lacked the funds to cast an image. The delicate and labor-intensive modeled image survives as a unique example from an otherwise lost image-making tradition and is clearly a masterpiece in its own right.

Fig. 5. Spearhead (Mdung Rtse), 17th–18th century. Tibetan. Iron, gold, and silver. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, Arthur Ochs Sulzberger Gift, 2001 (2001.180)

At sacred Buddhist precincts, protective shrines (gonkhang) were dedicated to guardian deities and protectors of the teachings (dharmapalas). Within these dark shrines, the imagery was usually covered except during ceremonies. Armor and weapons, especially those bloodied in battle, were especially efficacious donations to these ferocious protectors. This spearhead was likely made specifically for such a shrine given the prominently placed seed syllable kyai done in gold, which would have been used to invoke a deity in ritual contexts. In some instances, these weapons exhibit iconography related to the original users' desire for protection in battle, but much of the embellishment also relates to their function as offerings.

All of these artworks were created to help facilitate a devotee's access to the gods and the more elusive Buddhist idea of transcendence—the dharma. One of the ways for a monk or nun to accomplish this was to visualize and align oneself with one of the many Buddhist deities in the Vajrayana pantheon.

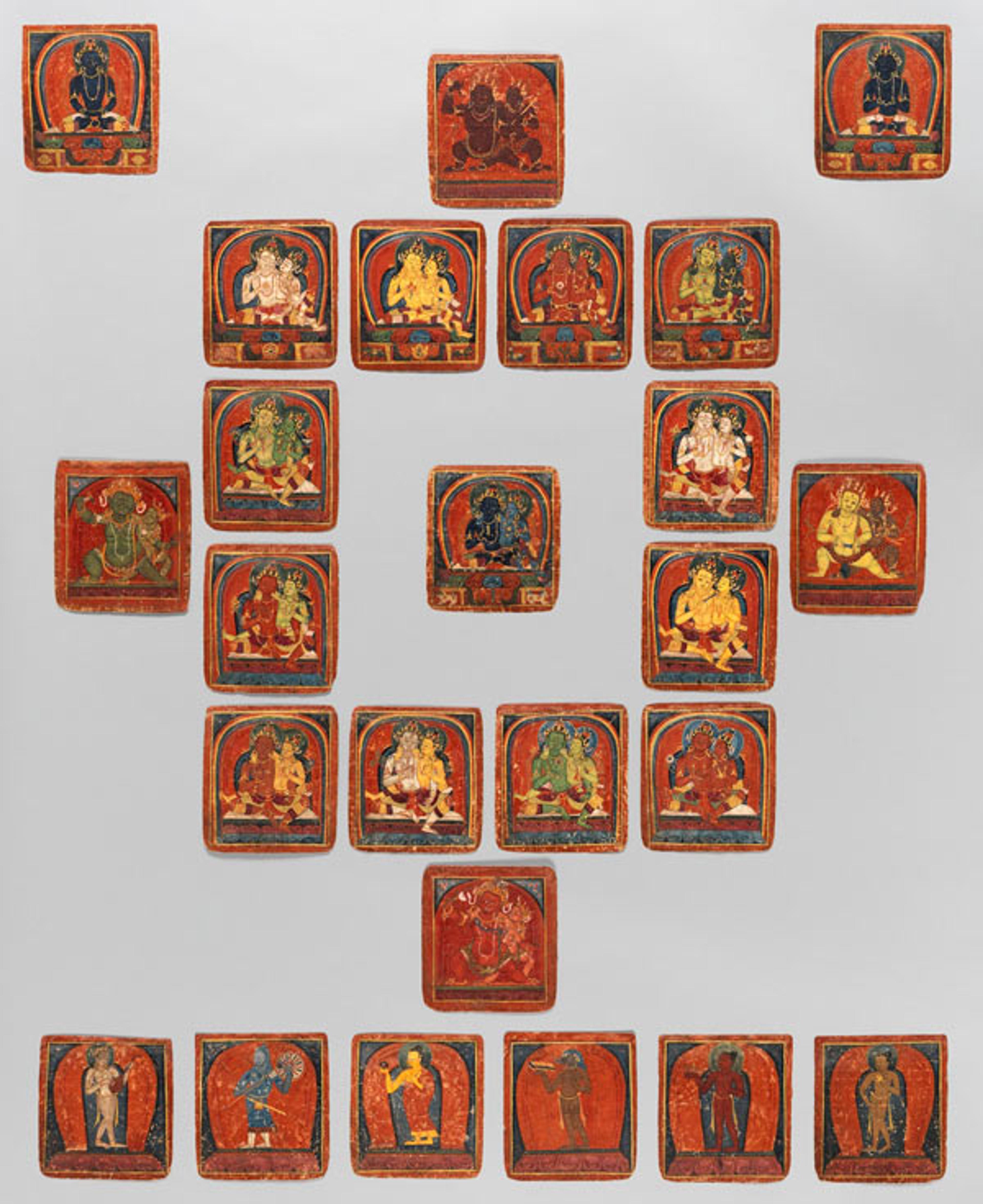

Fig. 6. Set of twenty-five initiation cards (tsakalis) organized as a mandala, early 15th century. Tibet. Opaque watercolor on paper. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Rogers Fund, 2000 (2000.282.1-.25)

Tsakali cards were used by itinerant teachers moving from one monastery to another to empower a practitioner to evoke a particular Buddhist deity (Fig. 5). First, the disciple sought permission from the deity, either through a dream or under the guidance of a teacher. The associated ritual involved visualizing the deity as described in recited mantras (incantations) and with an image—in this case, the deity represented on the tsakali. When laid on the ground in the form of a mandala, as seen here, the cards created a fixed sacred space like that of a temple.

The cards form a mandala if the first of these ordered cards is placed in the middle and the following cards are arranged clockwise, as is auspicious. The bodhisattvas Samantabhadra (male) and Sambantabhadri (female), appearing in the upper corners, have as their esoteric counterpart the central and most important figure, Vajrasattva. While no text explains this specific mandala, the Maha Vairochana sutra tells us that Vajrasattva should be venerated prior to undertaking advanced tantric techniques in order to purify the mind. This accords with the inscriptions on the back of each card, which associate certain mental states with each deity and delusions, such as pride, jealousy, and hatred, with each of the possible rebirths. It is remarkable that these cards, perhaps the earliest ordered set of tsakali that survives intact, together form a mandala suitable for the ritual of initiation.

This is the first in a series of blog posts by Met curators and conservators on specific works of art or other aspects of Sacred Traditions of the Himalayas. You'll be able to follow along by viewing all posts tagged "Sacred Traditions of the Himalayas." You can also join the conversation on social media by using the hashtag #SacredTraditions.