Two of the three enormous Tiepolo canvases located in gallery 600. The paintings had been put on new stretchers that returned them to their original, irregular shape, which necessitated our creating custom-made frames for them.

«That's right; our newly acquired Jabach portrait arrived at the Museum with no frame. When I inquired about the omission, I was told that the frame it had had in London was not worth sending over. Besides, that frame no longer fit the picture, since it had been made when the top of the canvas was folded over. (See "The Jabach Conservation Continued: Next Steps" for more on the fold in the canvas.)»

This is hardly the first time we've had to find a frame for a newly acquired painting. But not since we had frames made for the three enormous canvases by Giovanni Battista Tiepolo that greet visitors in gallery 600 at the top of the Grand Staircase have we had to deal with a work of this scale. (In 1994, the Tiepolos had been put on newly made stretchers that returned them to their original, irregular shape, and this necessitated the making of new frames, the cross-section of which was based on a period molding we had in our collection.)

Normally, we prefer to use a period frame: something that might have been put on the picture by the artist or the first owner. When this isn't possible, we try to have a copy made of an existing frame. For example, we have a Renaissance tondo—that is, a circular picture—by the Florentine painter Lorenzo di Credi. It's currently being worked on so that we can exhibit it in the galleries. But the frame is an awful, modern concoction. Fortunately, a workshop replica of the picture that belongs to the Uffizi in Florence is in its original frame, so we contracted a master carver and gilder there to copy it. Success!

Newly gilded frame made in Florence for the Museum's tondo by Lorenzo di Credi. It was copied from an original fifteenth-century frame. Photograph by Julia Markert

Unfortunately, that solution won't work here, but the artist left us some hints about contemporary frames in the painting itself. Le Brun shows two landscapes hanging on the back wall of the room in which Jabach and his family are seated. One is in an oval frame with bunched leaves—typical of the period under Louis XIII. The other, larger frame is much simpler and in its detailing already looks ahead to what we think of as Neoclassical frames. Actually, the frames in the painting are very much like the moldings that decorate the interior of the chateau of Vaux-le-Vicomte, where Le Brun worked with the architect Louis Le Vau.

Left: Detail of the two pictures hanging on the wall behind the family in the Jabach portrait (before conservation). Right: A room in the chateau of Vaux-le-Vicomte, where Le Brun worked with architect Louis Le Vau. Photograph courtesy of pixgood.com

We considered many options and proposals for the Jabach frame. We all felt that since the picture would not be part of a period interior but would hang in a gallery, the flat, architectural molding of the type seen at Vaux-le-Vicomte would be inappropriate. Ultimately, we think we found what we wanted by looking through our own collection. We settled on a grand Louis XIV frame on a portrait of the young Louis XV by Hyacinthe Rigaud.

Details of the grand Louis XIV frame on a portrait of the young Louis XV by Hyacinthe Rigaud in the Museum's collection. Photographs by Keith Christiansen

It seemed to all of us that if we eliminated the decorative elements in the corners and centers of the frame we would have a molding that answered to what we thought was needed: a period-style molding that was simple but elegant, with a sculptural quality that would hold up to the objects portrayed in the picture yet was at the same time discreet.

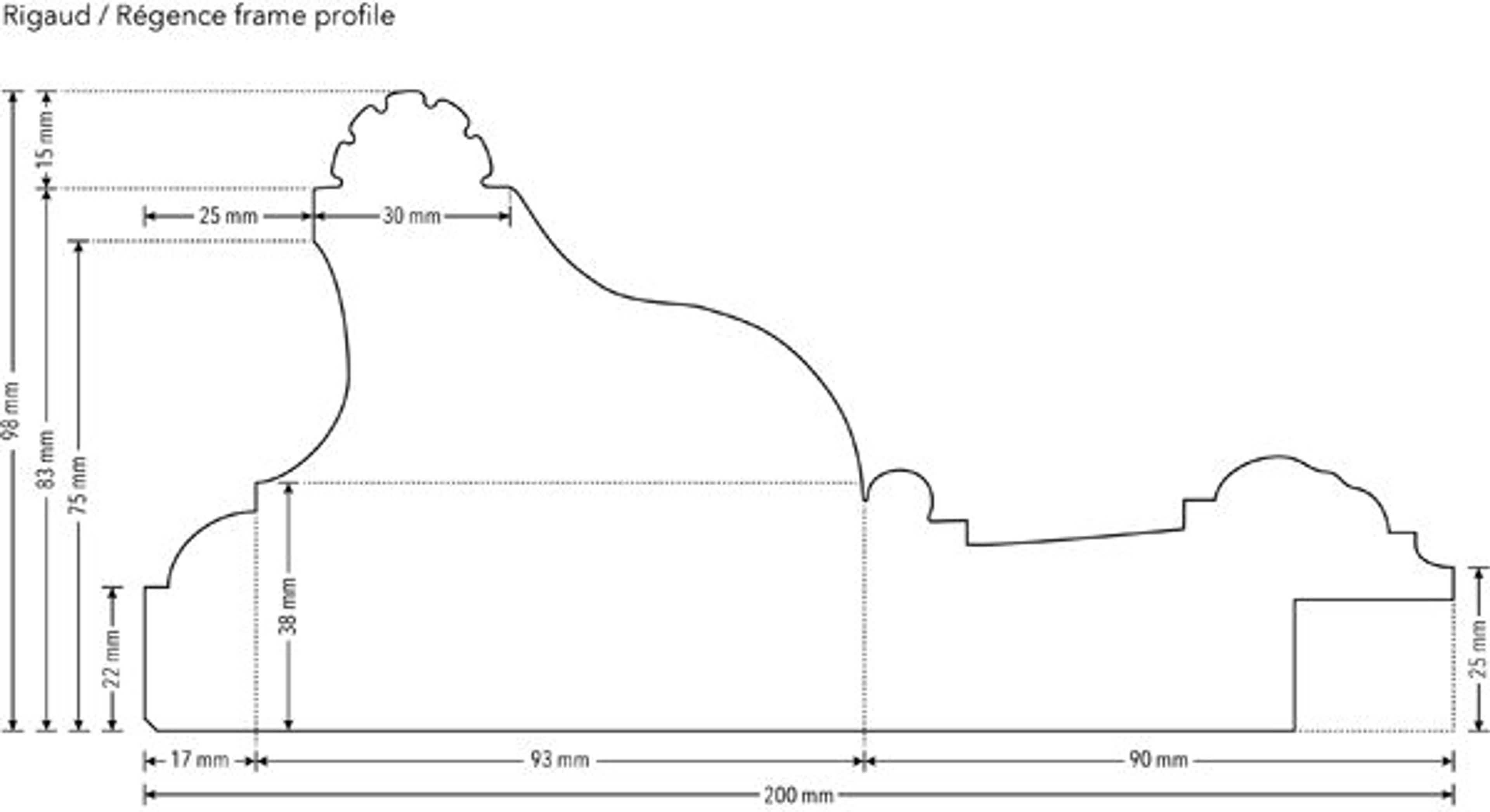

Conservators George Bisacca and Cynthia Moyer worked with Evan Read, associate manager for technical documentation, to create a diagram for the frame maker that shows a cross-section of the Rigaud frame.

Diagram of the cross-section of the proposed frame done by Evan Read

They are also making casts of the ornamental elements that have been sent to the frame maker in Paris.

Casts of the Rigaud frame's ornamental elements that have been sent to Paris, where the frame for the Jabach picture is being made. Photograph by George Bisacca

I hope to have the occasion to check on the progress and the gilding when I am in France in December. The finished frame will have to be sent in four pieces and then assembled here—we hope around the time that the picture is ready to go on view.