Charles Le Brun (French, 1619–1690). Everhard Jabach (1618–1695) and His Family (detail, before conservation), ca. 1660. Oil on canvas; 110 1/4 x 129 1/8 in. (280 x 328 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, Mrs. Charles Wrightsman Gift, 2014 (2014.250)

«While Michael Gallagher has been busy dealing with the structural issues of Charles Le Brun's great family portrait, I have felt privileged to be an attentive observer. But I have also been thinking about one of the many features that makes this painting so fascinating—the fact that Le Brun included his own reflection in a black-framed mirror propped on a table.»

The presence of a large, ebony-framed mirror in the work is not surprising; they were expensive and were displayed in the public rooms of a house—at Versailles, they became an ostentatious display of wealth and power—but the decision that a mirror in a family portrait would reflect the image of the artist at work cannot have been taken casually. It must have been approved, if not actually requested, by the patron, the German-born banker, merchant, and art collector–cum-dealer, Everhard Jabach.

Some of you may be reminded of Jan van Eyck's celebrated portrait of 1434 showing John Arnolfini and his wife. In that work, there is depicted a circular mirror that in its convex surface reflects the backs of the two principal figures, as well as two other men apparently entering the room through a door. (At that date, the technology for producing larger, flat mirrors did not exist.) Introducing a mirror was an ingenious way of extending the notional space of the picture so that it seems to embrace that of the viewer (though of course, because we are obviously not reflected in the mirror, we are made acutely aware of the painting as a fiction). The idea was immediately imitated by others: see the Museum's paintings by Petrus Christus (A Goldsmith in his Shop) and Juan de Flandes (The Marriage Feast at Cana).

Jan van Eyck (Netherlandish, ca. 1390–1441). Portrait of John Arnolfini and his Wife (detail), 1434. Oil on oak. National Gallery, London. Image via Wikimedia Commons

From the mid-sixteenth through the early nineteenth century, Van Eyck's picture belonged to the Spanish royal collections, and there is no question that Velázquez knew it and, indeed, had it in mind when he painted his grand canvas, Las Meninas, in which, once again, a black-framed mirror adorns the back wall. In it we see reflected the king and queen paying a visit to the artist's studio. Or are they the ones posing for the picture he is painting? Or is something else at work here? The ambiguity—surely intended by Velázquez—has inspired a literature of its own.

Velázquez (Diego Rodríguez de Silva y Velázquez) (Spanish, 1599–1660). Las Meninas, or The Family of Felipe IV (detail), ca. 1656. Oil on canvas. Museo del Prado, Madrid. Image via Wikimedia Commons

Le Brun could not have known either work. But the idea of incorporating a mirror reflecting someone positioned outside the picture field does not depend on something as simple as an imagined dependence of one work on another. Because, you see, the mirrored reflection is an idea—a conceit that encompasses a conception of the relation of art to nature and reality, which was something that has engaged many artists from the Renaissance to the present. Art as the mirror of Nature. It is an idea that can be, and was, taken in many directions.

Here are just a few well-known examples that I have chosen, almost at random, of painters using reflections on various surfaces to inspire our admiration—and encourage discussion among cognoscenti, an increasingly important part of artistic creativity beginning in the Renaissance.

Hans Memling (Netherlandish, active by 1465–died 1494). St. George and Donor (detail), ca. 1480. Alte Pinakothek, Munich. Photograph by Keith Christiansen

In this detail of a painting by Hans Memling in the Alte Pinakothek, Munich, the artist shows not only the reflections of the figures of the Holy Family toward which the saint gestures, but a church located beyond the picture field, thereby suggesting the vastness of the space and the picture as a fragment of reality.

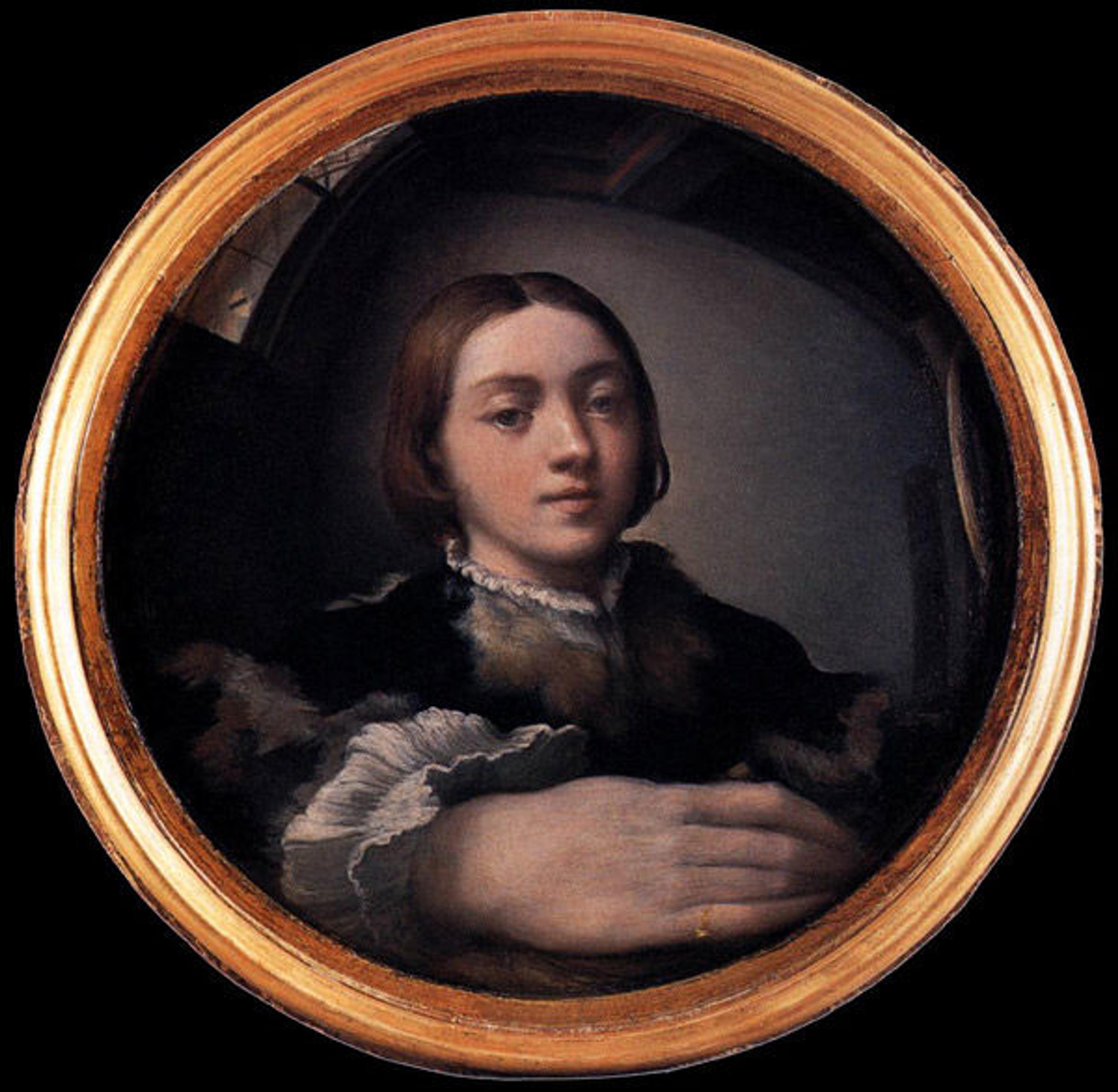

Parmigianino (Girolamo Francesco Maria Mazzola) (Italian, 1503–1540). Self-Portrait in a Convex Mirror, ca. 1524. Oil on panel. Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna. Image via WikiArt

For his self-portrait, the twenty-one-year-old Parmigianino used a convex piece of wood to simulate a real mirror—a perfect emblem of Art as the mirror of Nature. Notice the way Parmigianino employs the distorting curve of the mirror to emphasize his hand as the means by which his genius is made manifest.

Andrea Solario (Italian, ca. 1465–1524). Saint John the Baptist's Head, 1507. Oil on poplar. Musée du Louvre, Paris (M.I. 735) © Musée du Louvre/A. Dequier - M. Bard

In Saint John the Baptist's Head, Andrea Solario shows his own image as an inverted reflection in the stem of the dish.

Peter Paul Rubens (Flemish, 1577–1640). Venus at a Mirror, 1613–14. The Princely Liechtenstein Collections, Vienna. Image via Wikimedia Commons

In Peter Paul Rubens's astonishing painting of Venus at her toilette, we make eye contact with the goddess by means of her reflection—which, of course, is itself a fiction. We gaze at Venus and, by means of the mirror, she gazes at us gazing at her.

Georges de La Tour (French, 1593–1653). The Penitent Magdalen (detail), ca. 1640. Oil on canvas. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Charles Wrightsman, 1978 (1978.517)

In Georges de La Tour's The Penitent Magdalen, Mary Magdalene contemplates the reflection of a candle flame in a luxuriously framed mirror: a metaphor for the brevity and vanity of life. ("And all our yesterdays have lighted fools / The way to dusty death. Out, out, brief candle!" [Macbeth, Act V, scene v])

So what do we think Le Brun and his patron meant to convey? Does the reflection of the artist working on a canvas—not, incidentally, the portrait of Jabach and his family (the canvas in the mirror is too small for that)—suggest Le Brun's employment by Jabach in a socially dependent position? Or, contrariwise, does it commemorate the close friendship of patron and painter that, according to Le Brun's biographer, existed between the two? Is Le Brun's reflected presence emblematic of Jabach's consuming interest in painting? Or is it, rather, a comment on Le Brun's idea of portraiture as mimesis—something different from the imaginative recreation of a mythological story, allegory, or historical event for which he was famous? Does it suggest that, in addition to the picture being a magisterial exercise in portraiture, it is an allegory of the art of painting—in a vein similar to what many scholars have posited for Velázquez's masterpiece?

In the 2002 translation of her book on the history of the mirror, Sabine Melchior-Bonnet notes (pp. 164–65): "An instrument of reflection, [the mirror] also offered itself as a model of reflection. In the seventeenth century, the experience of the self was rooted in a clear-sighted gaze sharpened by the mirror and the exercise of reflective thought." Fantastic!

I like to imagine discussions of this sort taking place in front of the painting itself once Michael has finished his work and the frame arrives from Paris. Because this picture is a work of extraordinary richness.