«Regarded by many as the creator of the poster in America, Edward Penfield was born in Brooklyn, New York, in 1866. After initially joining Harper and Brothers at the age of 25 as a staff artist and editor, he received a promotion to director after just two years. Seemingly overnight, Penfield became the company's artist of choice for seven years following the publication of his first poster for Harper's in 1893, and readers celebrated his designs for their boldness, precision, and comical twist.»

Left: Edward Penfield (American, 1866–1925) for Harper's. Harper's: April, 1894. Lithograph; Sheet: 17 13/16 x 13 1/16 in. (45.3 x 33.1 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, Leonard A. Lauder Gift, 1990 (1990.1105.1)

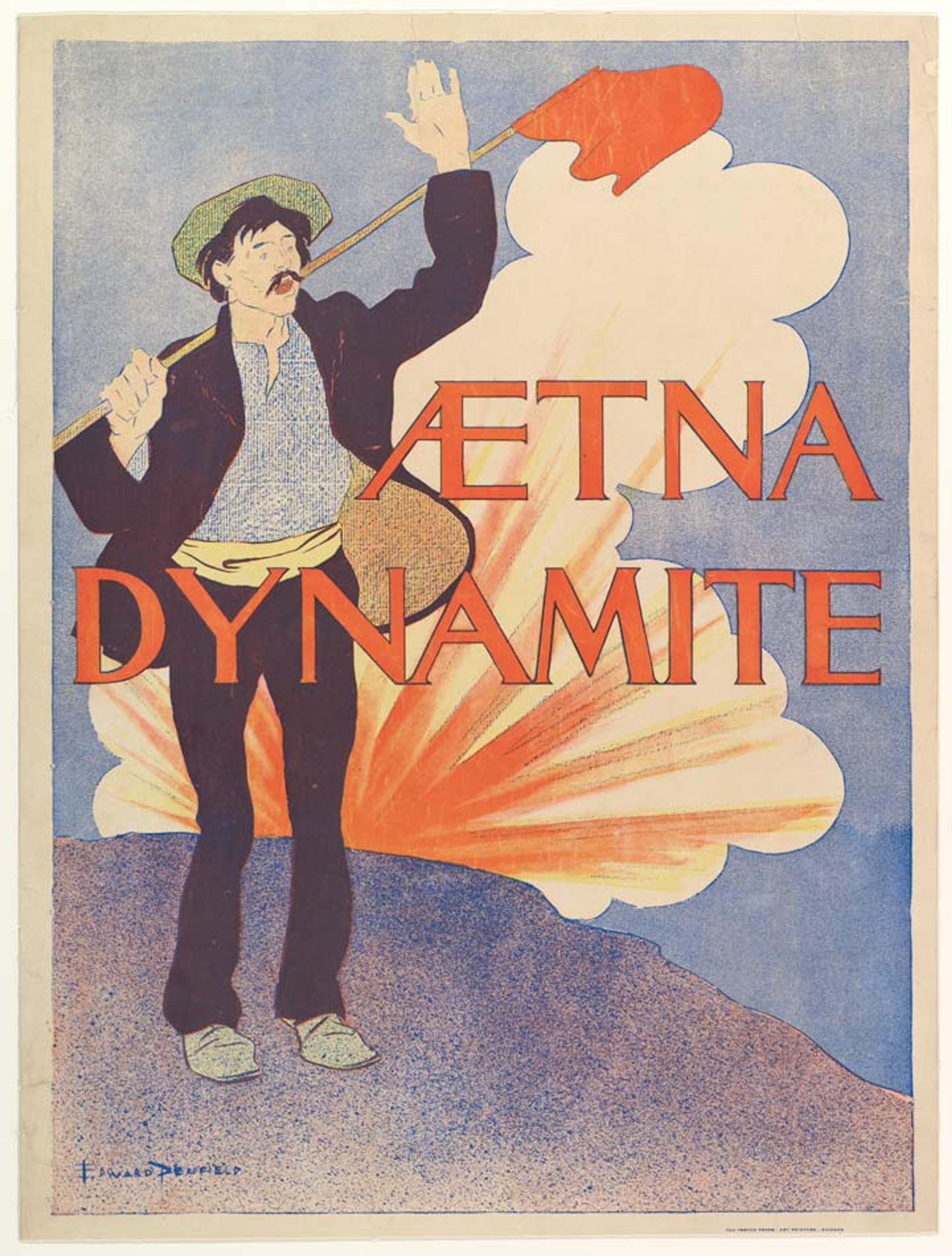

Purchased by The Met through the generous support of Mr. Leonard Lauder, Edward Penfield's Aetna Dynamite poster makes reference to a significant period in the history of dynamite, and demonstrates the power of skillfully designed advertisements to communicate veiled messages. The poster depicts a man in what would have been associated with European dress, raising a red flag against the backdrop of an explosion of orange and red. The image first appears to be a straightforward, futuristic celebration of the power of this new material and its use by the common man; symbolically, though, its imagery relates to the history of dynamite within the anarchic movement, then rampant in Europe and Chicago, where this poster was printed.

Edward Penfield (American, 1866–1925) for Aetna Powder Company. Aetna Dynamite, 1895. Lithograph; Sheet: 18 13/16 x 14 3/16 in. (47.8 x 36 cm), Image: 18 1/16 x 13 1/4 in. (45.8 x 33.6 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, The Lauder Foundation, Evelyn H. and Leonard A. Lauder Fund Gift, 1987 (1987.1010)

After Europe and the United States authorized the production and sale of dynamite in 1875, anarchists across Europe wrote prolifically about the explosive. Johan Most, a German bookbinder, was named the "apostle of dynamite" after publishing an article claiming that "it was with the power of dynamite" that anarchists could at last "destroy the capitalist regime" (John Merriman, The Dynamite Club: How a Bombing in Fin-de-Siècle Paris Ignited the Age of Modern Terror [New Haven: Yale University Press, 2016], 75). In Russia, the People's Will anarchist group made dynamite their official weapon, and similar groups in the United States echoed this tone. A writer for the popular anarchist newspaper The Alarm underlined the movement's disconcerting reverence for the explosive in 1885, extolling:

Dynamite! . . . Stuff several pounds of this sublime stuff into an inch pipe (gas or water pipe), plug up both ends, insert a cap with a fuse attached, place this in the immediate vicinity of a lot of rich loafers who live by the sweat of other people's brows, and light the fuse. A most cheerful and gratifying result will follow. . . . A pound of this good stuff beats a bushel of ballots all hollow—and don't you forget it! (Hertha Pauli, Alfred Nobel: Dynamite King, Architect of Peace (New York: L.B. Fischer, 1942), 188).

William B. Williams, in his book History of the Manufacture of Explosives for the World War, 1917–1918, speculated that some of the initial coupling of dynamite with anarchy began in Paris, where one group, Les Dynamitards, named themselves directly after the explosive.

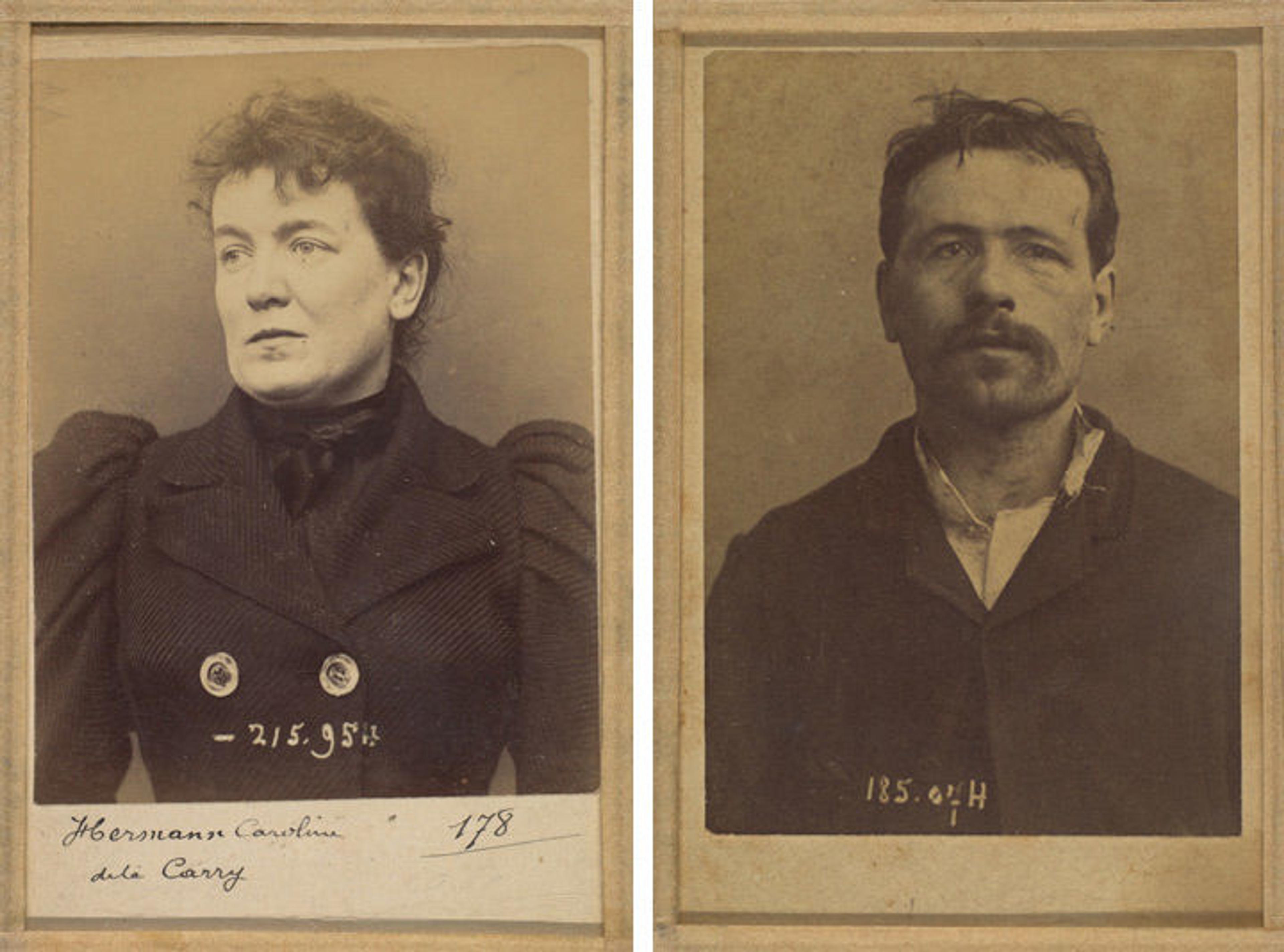

Caroline Herman (left) and François Claudius Kœnigstein Ravachol (right), two high-profile anarchists captured by police in the 1890s during a wave of bombings and assassination attempts carried out throughout Paris. Left: Alphonse Bertillon (French, 1853–1914). Herman. Caroline. 33 ans, née à Paris Vllle. Couturière. Disposition du Préfet (Anarchie). 21/3/94, 1894. Albumen silver print from glass negative; 10.5 x 7 x 0.5 cm (4 1/8 x 2 3/4 x 3/16 in.). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gilman Collection, Museum Purchase, 2005 (2005.100.375.205). Right: Alphonse Bertillon (French, 1853–1914). Ravachol. François Claudius Kœnigstein. 33 ans, né à St-Chamond (Loire). Condamné le 27/4/92, 1892. Albumen silver print from glass negative; 10.5 x 7 x 0.5 cm (4 1/8 x 2 3/4 x 3/16 in.). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gilman Collection, Museum Purchase, 2005 (2005.100.375.348)

In Chicago, both dynamite and red flags were associated with social revolution. A recent PBS documentary on late 19th-century labor movements in Chicago, Chicago: City of the Century, illustrates the political atmosphere at the time Penfield designed the poster for Aetna. As one historian explained:

The Sunday picnics that Chicago's Germans enjoyed became more than picnics. They were a chance to spread the word and recruit. One Sunday, anarchist leader Samuel Fielden spoke of the wonders of a new invention, dynamite, which, he said, "science has placed within the reach of the oppressed." On Thanksgiving Day 1884, the anarchists unveiled their new symbol. The black flag of hunger and death joined the red flag of social change.

Sadly, the intentions behind the invention of dynamite were in direct opposition to the associations for which it later became known. Primarily conceived as a safety precaution, dynamite served as a more manageable alternative to earlier forms of black-powder explosives. The famed scientist Alfred Nobel worked as a young man in his father's arms factory in his native Sweden. After obtaining a degree in chemistry in the United States, Nobel returned to Sweden to work with his family. At 31 years old, a deadly explosion at the plant killed his younger brother. Deeply distressed, Nobel was determined to create a safer explosive, which ultimately resulted in his patenting of dynamite, in 1867.

From the late 19th to the early 20th century, the manufacturing of explosives such as dynamite was a thriving industry, one largely controlled by the United States. By 1914, the DuPont explosive factory of Wilmington, Delaware, had become one of the nation's largest firms, and Aetna Explosives, founded by a former executive at DuPont, "manufactured smokeless powder for the Russian, French, and English Governments and finally for the United States Government, and in October 1918, was delivering at the rate of 1,500,000 pounds of smokeless powder per month" (William B. Williams, History of the Manufacture of Explosives for the World War, 1917–1918 [Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1920]).

Despite regular accidents, manufacturers experienced little decline in profit, as the explosive material had quickly become a vital tool for many. Companies advertised dynamite as proof of the many ways in which industrial advancement could ease the strains of manual labor, boost the economy, and improve the daily lives of industrialists, farmers, and factory workers alike, promoting its use for railroad and bridge construction projects, agricultural advancement, and military purposes.

Penfield's poster serves as a visual notice of the dichotomy of meaning associated with the material: dynamite was at once advertised as the ultimate tool for industrialist expansion, as well as the symbol of uprising used by anarchic rioters at Chicago's Great Upheaval; it was the explosive used to lessen the need and expense of manual labor, and the anarchist manual laborer's romanticized weapon for revolting simply, cheaply, and loudly. The man in the poster, therefore, raises questions as to what side the artist, or Aetna, meant to represent. To what audience is the poster speaking?

After World War I, posters and advertisements for dynamite changed drastically in the United States. Repulsion for the mechanization that destroyed the lives of many replaced the glorification of destruction propounded by Futurist and revolutionary groups. As the American public inextricably began to associate dynamite with the traumas of mechanical warfare, advertisers needed to find creative solutions to reassociate explosives with productivity and goodwill, and they once again turned to artists to communicate such messages to the American public.

In a 1920 article published in Advertising and Selling magazine, J.H. Lewis highlighted the predicament facing many explosive companies such as Aetna, and how they were to overcome these challenges. As Lewis explained:

In war times it is needless to say that the powder market assumes considerable proportions. . . . Fortunately wars are scarce and no manufacturer of explosives harbors the idea of waiting around for an outbreak of hostilities in order to remain in business . . . his advertising and marketing problem is to divorce explosives in the public mind from association with the battlefield.

Many agencies strategically chose to "divorce explosives" from its previous associations by focusing on their capacity to aid Americans in rebuilding, both economically and effectively.

Considered within the context of the history of dynamite, Edward Penfield's poster is multifaceted and rich with symbolism. As is the case with many posters of the late 19th and early 20th centuries, there is much in their design that speaks to the history and context of the materials advertised and to the life of the artist behind their creation.

The Met holds one of the largest collections of posters and works on paper in the world, many of which can be viewed in the Study Room for Drawings and Prints, which is open five days a week, by appointment.

References

Merriman, John. The Dynamite Club: How a Bombing in Fin-de-Siècle Paris Ignited the Age of Modern Terror. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2016.

Pauli, Hertha. Alfred Nobel: Dynamite King, Architect of Peace. New York: L.B. Fischer, 1942.

Williams, William B. History of the Manufacture of Explosives for the World War, 1917–1918. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1920.