Left: Léon Bakst (Russian, 1866–1924). Costume Study for Vaslav Nijinsky in the Role of Iksender in the Ballet La Péri (The Flower of Immortality), dated 1922. Watercolor and gold and silver paints over graphite, 26 5/8 x 19 1/4 in. (67.6 x 48.9 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Sir Joseph Duveen, 1922 (22.226.1). Right: Léon Bakst (Russian, 1866–1924). Costume Design for a Eunuch in Schéhérazade, ca. 1910. Gouache and graphite, heightened with gold paint, 17 x 10 3/4 in. (43.2 x 27.3 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Bequest of Sallie Blumenthal, 2015 (2015.787.6)

«This summer, the selection of drawings in the Robert Wood Johnson, Jr. Gallery features a group of designs for the Ballets Russes by the famous Russian artist Léon Bakst (1866–1924). The Museum's holdings of the artist's work have been significantly enriched by a recent bequest from the late Mrs. Sallie Blumenthal, and now reflect a broad range of graphic material produced by Bakst and his assistants to bring to life the transportative avant-garde ballet productions that took Europe by storm in the early 20th century.»

The Ballets Russes was founded by Sergei Diaghilev (Russian, 1872–1929), who, after unsuccessfully exploring his own artistic talents, had built a career as a connoisseur and impresario of Russian visual and performing arts at home as well as abroad. Bakst met Diaghilev in the 1890s and both became founding members of the movement Mir iskusstva (World of Art), which promoted modern Russian art through its periodical of the same name, and by organizing exhibitions and performances. The Ballets Russes was arguably one of the movement's most successful initiatives, offering an international stage and regular employment to many young Russian composers, choreographers, designers, and dancers under Diaghilev's directorship.

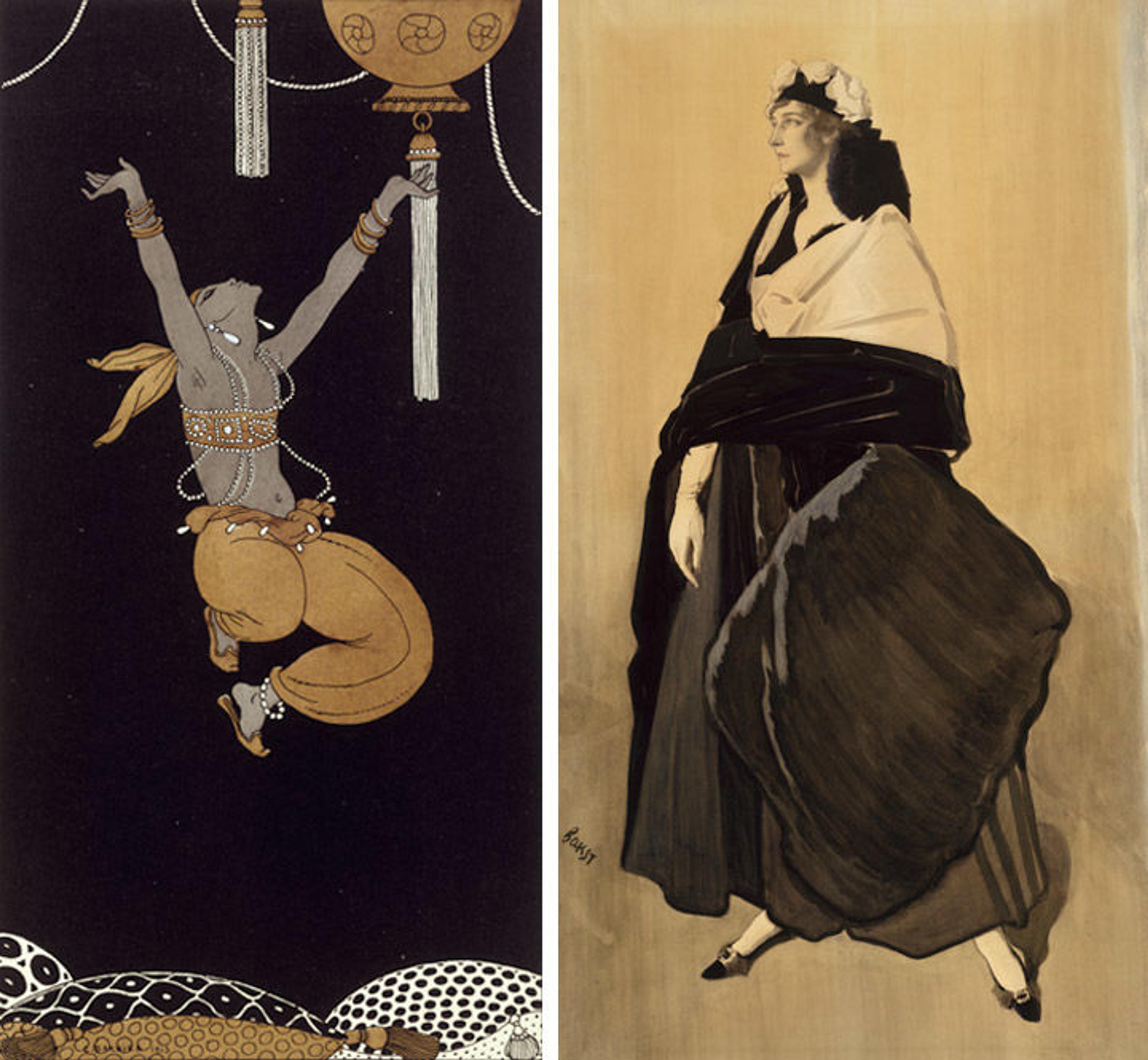

Left: George Barbier (French, 1882–1932). Nijinsky as the Golden Slave in Schéhérazade, from Nijinksi [London: C. W. Beaumont & Co.], 1913. Pochoir, 13 1/16 x 11 x 2 3/8 in. (33.2 x 28 x 6 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Mary Martin Fund, 1978 (1978.567). Right: Léon Bakst (Russian, 1866–1924). Portrait of Mme Ida Rubinstein, ca. 1910, Watercolor, gouache, and graphite on paper, mounted on canvas, 50 1/2 x 27 1/4 in. (128.3 x 69.2 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, The Chester Dale Collection, Bequest of Chester Dale, 1962 (64.97.1)

After organizing several highly successful cultural programs in Paris, Diaghilev staged a whole season of Russian ballet in the French capital in 1909, and its overwhelming popularity swayed him to make Paris the new home of the Ballets Russes. The company performed both traditional and newly commissioned productions—as many as four per year—that were brought to life by star performers such as Vaslav Niijnski (Russian, 1889–1950) and Ida Rubinstein (Russian, 1883–1960), who danced their routines in custom-designed costumes against dramatic backdrops that helped to invigorate the fantastical characters and alternate realities they portrayed.

While several Russian artists were involved in the creation of costumes and stage sets, in the early years before World War I it was Bakst who was celebrated most for his colorful and imaginative designs, and was regarded as the company's artistic director. The multimedia performances produced by the Ballets Russes had a beguiling and engrossing effect on its contemporary audiences, which we can glean, in part, from contemporary writings:

He [Nijinski] is, in truth, a stranger to the sad world of gravity, he flies through the air with a smile, and the eye follows in wonderment. [1]

Contemporary responses to the Russian ballet performances also reveal a particular sense of solace and escape that was felt at a time when Europe and the United States were suffering from the devastation and aftermath of World War I, as well as the consequences of the Russian October Revolution in 1917, which brought an end to the Tsarist regime and affected many members of the company itself.

We have our despair, our sadness, our violated love and this thing, most dread of all—the passing of the days between our hands . . . But in the spring, the Russian Ballets and Nijinski return. And all is forgotten. [2]

Léon Bakst (Russian, 1866–1924). Landscape with Shepherds, Set Design for the Ballet Daphnis and Chloé, [1911]. Watercolor over charcoal, 13 1/8 x 19 3/4 in. (33.3 x 50.2 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Sir Joseph Duveen, 1922 (22.226.2)

One of the particular strengths of Diaghilev's programming was that it showcased stories that represented history and cultures from all around the world, as though they were all cut from the same colorful cloth. In the early years, for example, the company staged several shows that were situated in Ancient Greece and the Near East. They were highly popular because these settings lend themselves well to exotic decors, colorful costumes, and erotically charged routines. Because of his own exotic features, Nijinski, in particular, effortlessly portrayed characters of various ethnicities—from the medieval Duke Albrecht of Silesia in Giselle (1910) to the Blue God in Le Dieu Bleu (1912).

While intoxicating because of the exotic and fantastical subject matter of many of these productions, they also oftentimes communicated certain core values that permeate the romances and tragedies presented in the ballets. The arcadian Daphnis and Chloé, performed in 1912 at the Théâtre du Châtelet in Paris, for one, exemplified how love prevails under difficult circumstances through the story of the two protagonists who first deny their true feelings for one another, but are reunited after overcoming many obstacles.

Left: Léon Bakst (Russian, 1866–1924). Costume Design for the Sultan Samarkand for the Ballet Schéhérazade, dated 1919. Watercolor, graphite, and gold paint, 11 11/16 x 5 3/4 in. (29.6 x 14.6 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Bequest of Sallie Blumenthal, 2015 (2015.787.12). Right: Léon Bakst (Russian, 1866–1924). Costume Design for a Woman from the Village, for the Ballet Daphnis and Chloé, dated 1912. Watercolor over graphite, 10 1/4 x 8 1/2 in. (26 x 21.6 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Bequest of Sallie Blumenthal, 2015 (2015.787.5)

Schéhérazade, performed in 1910 at the Théâtre national de l'Opéra in Paris, encompassed all of the above-mentioned elements and was one of the most successful ballets Bakst designed for the Ballets Russes. Not only did it feature both Vaslav Nijinski and Ida Rubinstein, but the exotic setting and colorful, often quite revealing costumes—which earned Bakst the questionable title of "erotomaniac"—proved a feast for the eye and were described as "a perfect tornado of color." Further increasing its popularity was the dramatic storyline, which told of a sultan who killed his 1,000 wives after each successive wedding night because he feared their infidelity, but was eventually swayed from continuing his tyranny by the clever Schéhérazade.

Left: Léon Bakst (Russian,1866–1924). Costume Design for a Female Courtier, Likely for the Ballet La Belle au Bois Dormant (Sleeping Beauty), ca. 1921. Watercolor over graphite, 11 1/2 x 6 1/2 in. (29.2 x 16.5 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Bequest of Sallie Blumenthal, 2015 (2015.787.7). Right: Léon Bakst (Russian, 1866–1924). Design for a Loom, Possibly for the Ballet Helen of Sparta, ca. 1912–1923. Graphite with watercolor and gouache, 11 x 9 in. (27.9 x 22.9 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Bequest of Sallie Blumenthal, 2015 (2015.787.14)

To create the illusory worlds of the Ballets Russes, Bakst worked out every detail on paper. He enriched his imagination through close study of the people, nature, and historical objects from private collections and museums he encountered during his travels, which allowed him to invoke a specific time and place for each individual production. In his drawings Bakst explored his vision for the mise-en-scène, from large overall impressions of the decor to the smallest detail, fretting over the design and choice of all objects used in the staging of a show.

To ensure that his vision was executed successfully, a whole range of different types of drawings were made to communicate important information about colors, measurements, and materials. Most designs, therefore, circulated in a number of copies, some by the hand of the master, others done by workshop assistants made by way of transfer paper.

Left: Léon Bakst (Russian, 1866–1924) or Workshop. Costume Design for La Fée des Poupées, 1903. Graphite on tracing paper, squared for transfer, 14 3/16 x 10 11/16 in. (36.1 x 27.1 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Nikita D. Lobanov, 1966 (66.753.4). Right: Léon Bakst (Russian, 1866–1924). Costume Design for the Ballet Thamar, dated 1918. Gouache, graphite, and silver paint, 19 x 12 1/4 in. (48.3 x 31.1 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Bequest of Sallie Blumenthal, 2015 (2015.787.17)

While Bakst is best known through his highly finished and very expressive presentation drawings, which were collected almost from the moment the ink on the pages had dried, it is only when we look at the vast array of drawings that have survived that we gain a true understanding not only of the splendor and ingenuity of Bakst's designs, but also of the meticulous planning and creative force that drove some of the most iconic ballet productions of the 20th century.

Notes

[1] Francis de Miomandre, foreword to Nijinski, by George Barbier (London: C. W. Beaumont & Co., 1913).

[2] Ibid.