Louise Bourgeois (American, 1911–2010). Spider Woman, 2005. Drypoint, sheet: 13 1/2 x 13 1/2 in. (34.3 x 34.3 cm); plate: 6 7/8 x 9 1/2 in. (17.5 x 24.1 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, John B. Turner Fund, 2006 (2006.17)

«Spider webs have always been a source of wonderment. Woven overnight of silken strands, they are not only models of industry and beauty, but also examples of nature's ingenuity and lethal power, as seen in their effectiveness at ensnaring and trapping the spider's prey. In various historical cultures, they have been associated with the crafts of spinning, weaving, and basketry. In a more contemporary analogy, the word "web" is used to describe the vast interconnectivity of the internet. Spider webs have also been an enduring source of artistic inspiration, as seen in a collection of works spanning three centuries currently on view in the Robert Wood Johnson, Jr. Gallery.»

For the Paris-born artist Louise Bourgeois, spiders were a recurring motif throughout her long career, appearing in numerous prints and drawings as well as in monumental outdoor sculpture. The theme was initially associated with her mother, a tapestry restorer, but grew to take on broader associations as a strong female protector against evil. Spider Woman, dating from the last decade of the artist's life, represents a female spider with a human face contained within an egg-shaped form. The vibrant scarlet ink is a color Bourgeois favored in her late work.

Vija Celmins (American, born Riga, Latvia, 1938). Web 2, 2000. Mezzotint, plate: 6 7/8 x 7 9/16 in. (17.4 x 19.2 cm); sheet: 18 x 14 3/4 in. (45.7 x 37.5 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, John B. Turner Fund, 2001 (2001.388). © 2010 Vija Celmins

Another female artist who embraced arachnoid imagery was Vija Celmins. Discussing her work in a 2002 interview with former Met curator Samantha Rippner, she pondered her attraction to the spider's web: "Maybe I identify with the spider. I'm the kind of person who works on something forever and then works on the same image again the next day. At any rate, the web showed up somewhere in my psyche." Creating her mezzotint print Web 2 would have been—like much of Celmins's work—a labor-intensive task. After roughening the surface of the metal plate so that it would catch ink, she then burnished the plate smooth in places, producing delicate pale lines that suggest individual strands in a light-against-dark effect.

Left: Otto Henry Bacher (American, 1856–1909). Arachne, 1884. Etching, printed in brown ink, with plate tone, sheet: 12 1/16 x 8 3/4 in. (30.6 x 22.3 cm); image: 11 7/16 x 8 5/16 in. (29 x 21.1 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Mrs. Otto H. Bacher, 1938 (38.14.2)

The practice of seeing the spider in anthropomorphic terms is not new. In Greek mythology, the mortal woman Arachne challenged the goddess Athena to a weaving contest. For the folly of seeking to compete with a god, she was transformed into a spider. In this 1884 etching by Otto Henry Bacher, an American printmaker influenced by the manner of James McNeill Whistler, Arachne's hair merges with strands of the web, as the weaver finds herself ensnared.

Candace Wheeler (American, 1827–1923). Spider Web, 1880s. Pen, black ink, and gouache with graphite scoring lines and corrections, sheet: 17 1/2 x 18 1/2 in. (44.5 x 47 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Sunworthy Wallcoverings, a Borden Company, 1987 (1987.1074.2)

Another play on the connection between weaving and webs can be found in this design by Candace Wheeler, an American designer of textiles and wallpapers for Aesthetic period interiors. This design for wallpaper dates to the first half of the 1880s. By repeating a form found in nature and layering it with a scattering of bees, she created a dense and stylized pattern.

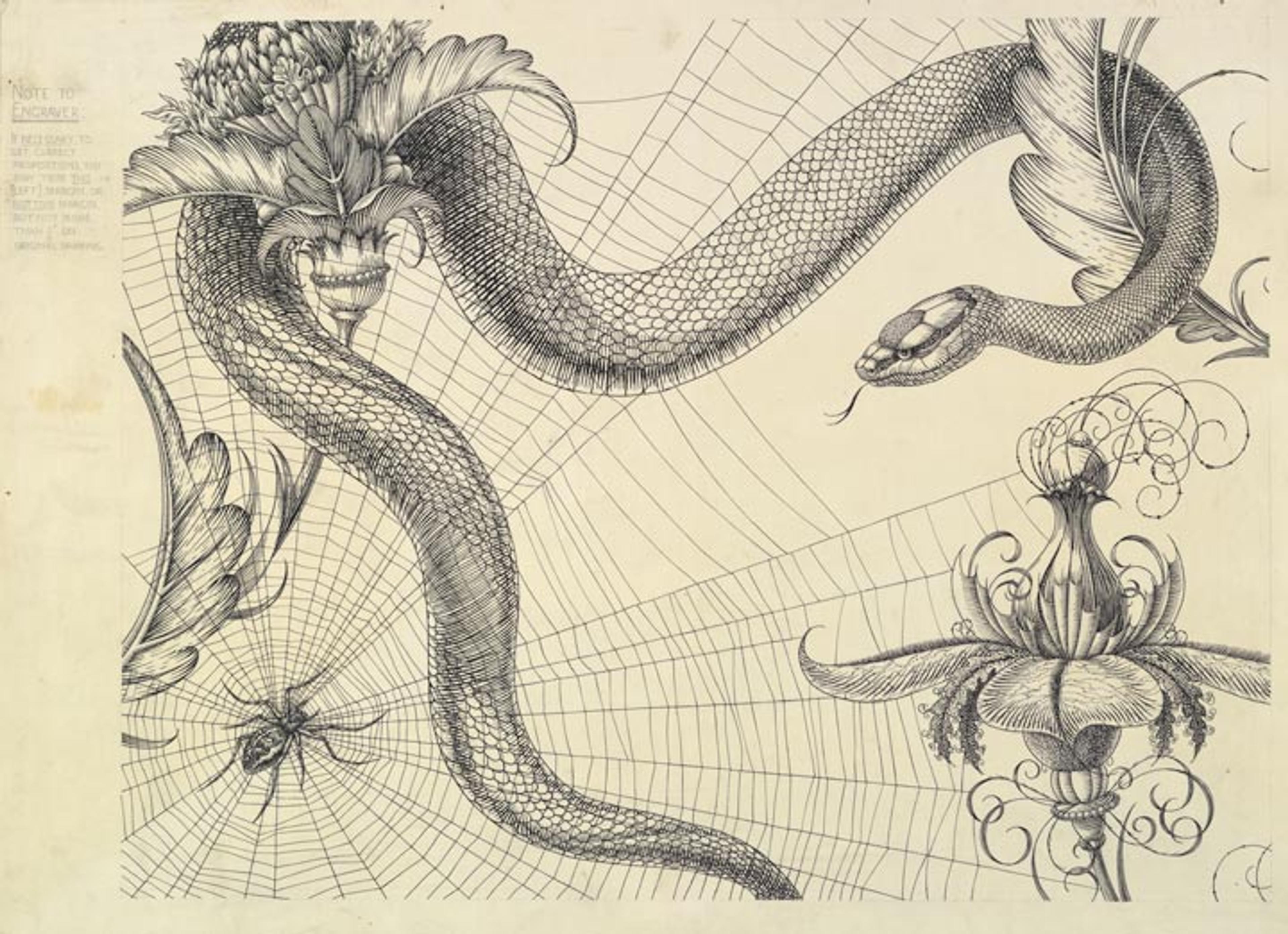

Henry Weston Keen (British, 1899–1935). Spider, Web, Snake, and Flowers, ca. 1930. Pen and ink, image: 14 1/8 x 18 1/2 in. (35.9 x 47 cm); sheet: 15 1/2 x 22 1/2 in. (39.3 x 57.2 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, The Elisha Whittelsey Collection, The Elisha Whittelsey Fund, 1967 (67.803.13)

Danger and thrill, rather than industry, are the focus of Henry Weston Keen's stylized face-off between spider and snake. Keen, a designer of book illustrations in the symbolist tradition, produced this elegant but macabre drawing to be engraved and printed as the endpaper for an edition of dramatist John Webster's tragedy The White Devil and the Duchess of Malfi published in London in 1930.

These works and others on view in gallery 690 through August 7, 2017, suggest the range of roles played by the spider in the human imagination. The balance, in the end, tips to seeing the positive side in these dangerous-looking and occasionally poisonous creatures. Notable events in spider-themed popular culture of the 20th-century include the publication of E.B. White's Charlotte's Web in 1952 and the appearance, 10 years later, of the Marvel Comics superhero Spiderman, whose powers included spinning webs from his wrists.

Related Link

Drawings and Prints: Selections from the Permanent Collection, on view at The Met Fifth Avenue through August 7, 2017