Unknown artist. Adolf de Meyer photographing Olga in a garden, 1900–1910. Gelatin silver print. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Lunn Gallery, 1980 (1980.1128.16)

Doesn't it seem wonderful that a camera should be privileged to be the means of providing one with exquisite memories? —Adolf de Meyer[1]

In a small, candid photograph made on a trip to the Alhambra in Spain, Baron Adolf de Meyer stands in the midst of a brick patio, delimited by a low, tiled wall and the lush vegetation of a Mediterranean garden beyond. With his back to the viewer, he is wholly absorbed in his pursuit, positioned next to a large-format view camera on a tripod, with one hand—holding a lens cap—on his hip, and his head bowed, focused on a watch diligently ticking the time of his negative's exposure. The subject of his camera's gaze is a seated woman in an elegant dress and ostentatious hat: his wife, Olga, his favorite and most frequent model.

From the time they met amidst the glamour of the London café society of the 1890s, until Olga's death in 1931, the two were nearly inseparable. By all accounts, theirs was a marriage of mutual admiration as well as convenience—de Meyer was gay and Olga, herself likely bisexual, had already married and quickly divorced a prince. She was raised by her mother in the seaside resort of Dieppe, where the future King Edward VII was a frequent visitor to their home, the evocatively named Villa Mystery. Rumors swirled that Olga was Edward VII's illegitimate daughter, and although false, he did provide her financial and social protection.

Adolf de Meyer (American [born France], 1868–1946). Olga de Meyer at the Alhambra, Grenada, Spain, ca. 1908. Carbon print, 2 1/16 x 2 15/16 in. (5.2 x 7.5 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, Mrs. Jackson Burke Gift, 1981 (1981.1010.42)

Olga's somewhat checkered upbringing benefitted from the legitimacy of de Meyer's title of baron, which he had inherited from his grandfather, while proximity to the monarch afforded the de Meyers a prominent place in London society. Notoriously chic and decidedly cosmopolitan, the couple surrounded themselves with an ever-revolving coterie of aristocrats and artists. As a photographer, de Meyer drew his inspiration from these social and artistic connections, from Olga and her innate sense of style, and from their travels together.

The de Meyers variously made their home in London's Cadogan Gardens, Paris, and New York, spent summers in Venice and Constantinople, winters in St. Moritz, and visited Greece, Spain, Morocco, Tangier, and Egypt. Their journeys together began in the spring of 1900, when the budding photographer and his new bride spent their honeymoon in Asia, visiting Hong Kong and Japan together, with de Meyer continuing on to India alone. (De Meyer had already visited Japan once, as part of a round-the-world trip that concluded shortly before he and Olga met.)

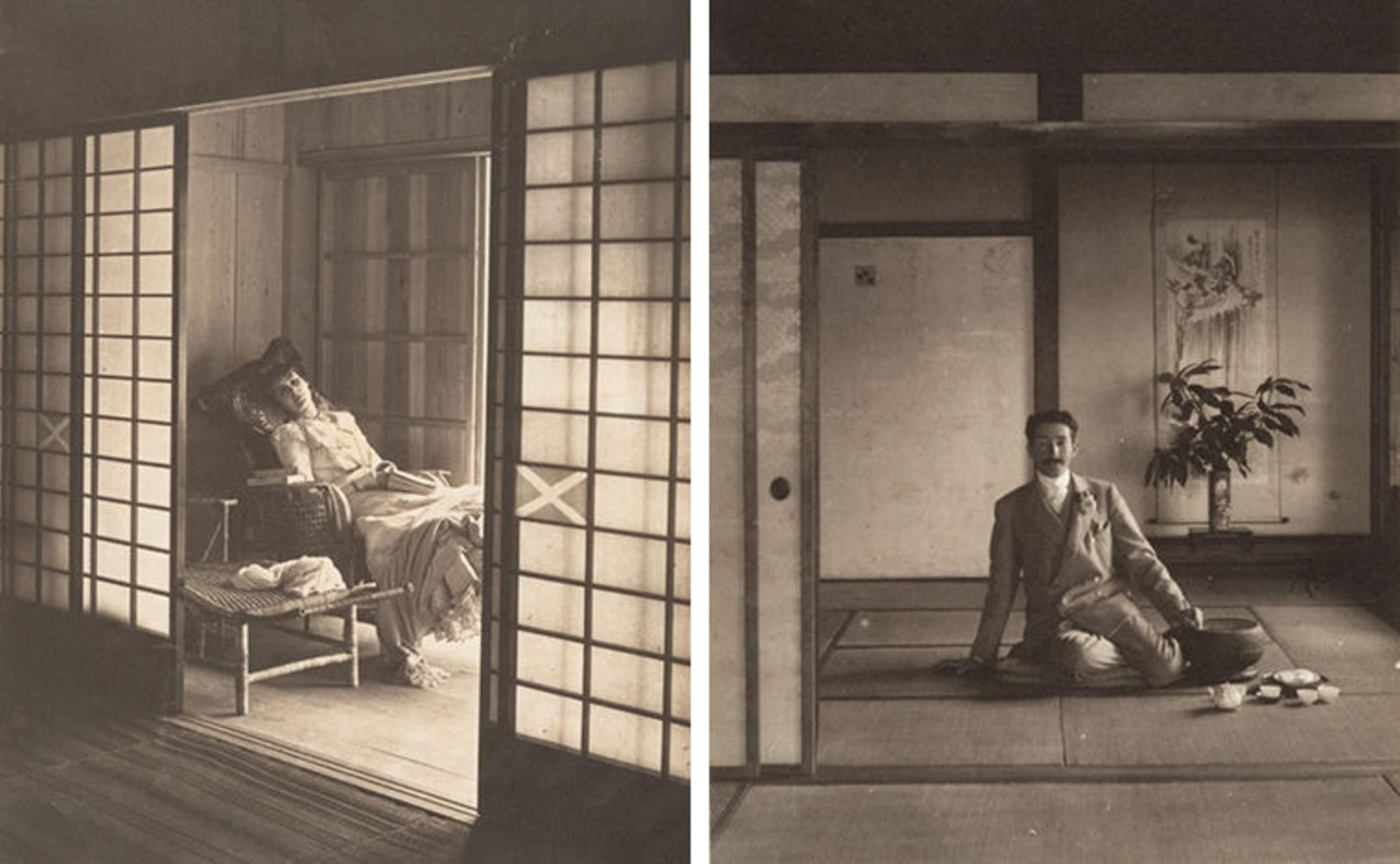

Left: Adolf de Meyer (American [born France], 1868–1946). Olga de Meyer, Japan, 1900. Platinum print, 7 5/8 x 5 15/16 in. (19.3 x 15.1 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, Mrs. Jackson Burke Gift, 1981 (1981.1010.1). Right: Adolf de Meyer (American [born France], 1868–1946). Self-portrait, Adolf de Meyer in Japanese House, 1900. Platinum print, 7 3/16 x 5 1/4 in. (18.3 x 13.3 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Purchase, Mrs. Jackson Burke Gift, 1981 (1981.1010.47)

The Met collection includes a group of fifty-nine photographs made during their journey, many of which are on view through April 8, 2018, in the exhibition Quicksilver Brilliance: Adolf de Meyer Photographs. Primarily a travelogue, the images record sites that would have been on the itinerary of any foreigner traveling through Meiji-era Japan, including monumental Buddhas, temples in Kyoto, Torii gates at Shinto shrines, Tokyo's Edo castle, gardens, and distinctive landscapes such as the waterfalls and mountains surrounding Nikko. However, these souvenirs also reveal de Meyer's experimentation with the camera, including his investigation of compositional strategies derived from Japanese art.

The de Meyers timed their travel to Japan for spring, likely following the advice of contemporary guidebooks, in order to see the cherry blossoms in full bloom. Indeed, the flowers—as well as blossoming irises—appear in several images. In one view through a garden window, the wooden doorjamb and mullions produce a flattened grid parallel to the picture plane. Rather than an opening into a three-dimensional space, however, the lack of horizon beyond creates a compressed layering of structures and vegetation. De Meyer made several such studies in and around the elegant hotels that catered to Westerners, where he and Olga stayed, which demonstrate his fascination with Japanese architecture and interior design.

In an affectionate portrait (above left), Olga pauses from her reading to look languidly at the camera. The composition, framed by the latticed panels of a sliding screen door, recalls the American painter James Abbott McNeill Whistler's paintings of women at rest in sympathetic interiors, as well as the influence of Vermeer through its device of a room viewed from an open door. As a kind of pendant to this picture, de Meyer also made a self-portrait in a Japanese interior. These studies reveal the artist's exploration of the posed figure within a highly aestheticized space, a characteristic element of his work that led to his success as a portraitist and fashion photographer.

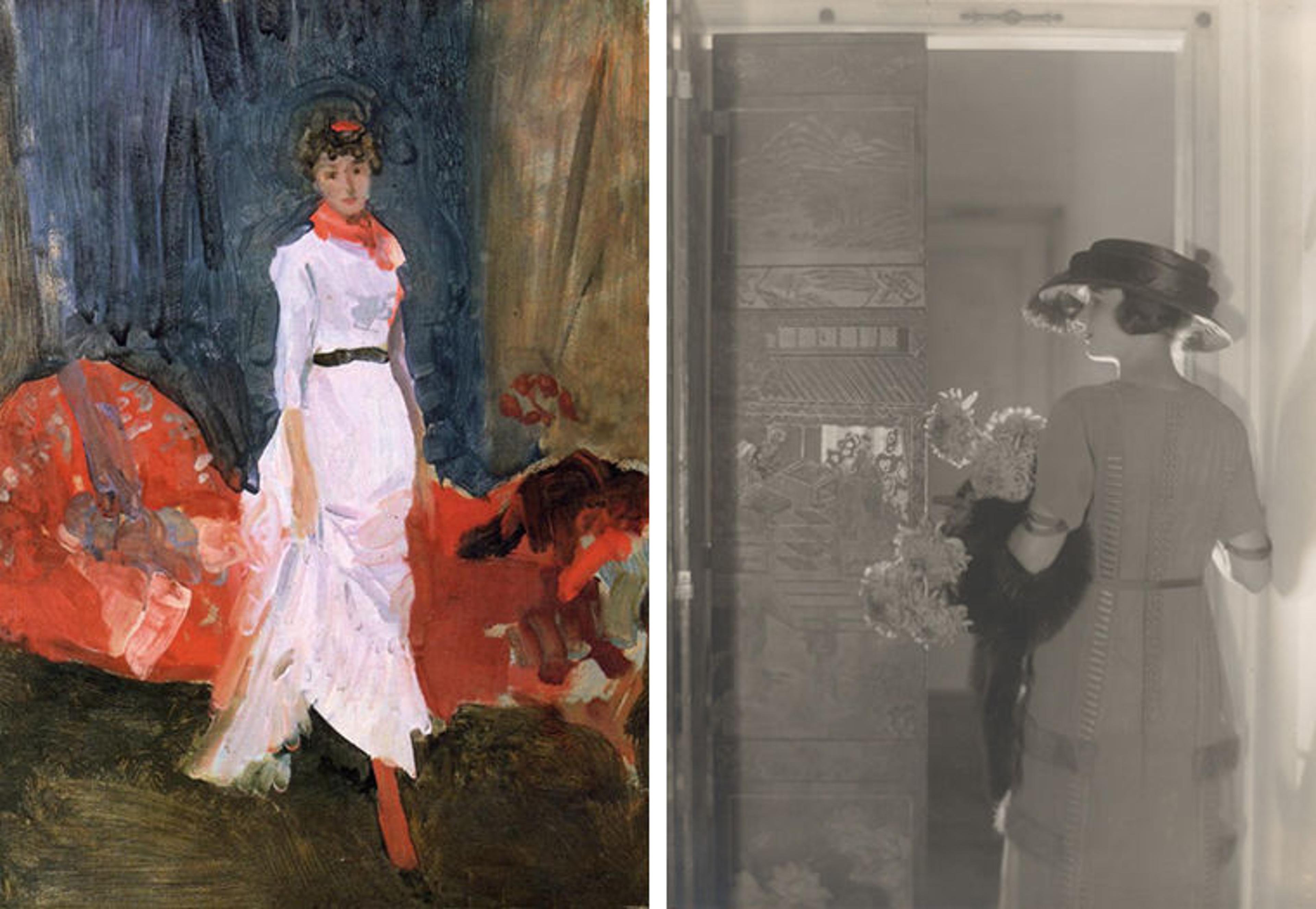

Left: James McNeill Whistler (American, 1834–1903). Scherzo: Arrangement in Pink, Red, and Purple, ca. 1885. Oil on panel, 12 x 9 in. (30.5 x 22.8 cm). The Cincinnati Art Museum (1920.38). Public-domain image via Wikimedia Commons. Right: Adolf de Meyer (American [born France], 1868–1946). Model wearing Chéruit afternoon dress, 1918. Gelatin silver print. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, The Elisha Whittelsey Collection, The Elisha Whittelsey Fund, 1975 (1975.502)

Upon returning to London, de Meyer made a series of still lifes of flowers that reveal the continued influence of Japanese aesthetics on his mature work. His masterful Shadows on the Wall (Chrysanthemums) boldly approaches abstraction in its minimalist rendering of the shadow cast by a vase of flowers against a blank wall. It also exhibits the strong influence of Whistler on de Meyer. The two were likely personally acquainted; Olga is the subject of Whistler's Scherzo: Arrangement in Pink, Red, and Purple, painted circa 1881–85. Like Whistler, de Meyer's interest in Japanese art and aesthetics led him to travel directly to the source. A key figure of the Aesthetic movement, Whistler followed the philosophy of "art for art's sake" and pursued in his paintings a harmonious balance of color and tone, privileging the ability of form to convey mood over realistic representation. Notably, de Meyer produced peach- and cerulean-tinted carbon prints of his Japanese pictures, which represent an early example of the artist's exploration of color and its tonal effects.

Right: Adolf de Meyer (American [born France], 1868–1946). The Shadows on the Wall (Chrysanthemums), ca. 1906. Platinum print, 13 11/16 x 10 1/2 in. (34.7 x 26.7 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, Alfred Stieglitz Collection, 1933 (33.43.231)

Contemporary critics recognized the affinity that de Meyer's photographs shared with Whistler's paintings. A 1914 article in the American Arts and Crafts movement periodical the Craftsman effused of de Meyer and his still lifes: "He is bent, in fact, on translating his material into a fantasy of abstract beauty. It is almost a rendition of matter into music. . . . Compared with these prints, which have the delicate perfection of some choice example of Japanese lacquer-work, too many other photographers seem technically inefficient."[2] Here, the association of visual art with music directly links de Meyer's art with that of Whistler, who titled his paintings "nocturnes" and "symphonies," based on the conventions of musical composition.

Shadows on the Wall (Crysanthemums) also evokes Whistler's Japonisme, expressed in that artist's work through the decorative objects depicted in his portraits and in compositional strategies drawn from Japanese prints. In de Meyer's photograph, the flattened composition—radical for its time—suggests the appearance of a lacquered screen, and was likely achieved through a combination of directional and backlighting. De Meyer later employed this innovative lighting technique in his fashion work, creating dynamic abstract backdrops for the elegant silhouettes of haute couture. Reflecting the eclecticism of Aesthetic movement interiors, his photographs often included silk fans, screens, carpets, and other decorative elements, including one example in The Met collection that appeared in the November 1918 issue of Vogue. More than a simple honeymoon, de Meyer's travels in Japan nourished Orientalist fictions, and gave rise to the subjects and compositions of many of his photographs.

Adolf de Meyer (American [born France], 1868–1946). Daibutsu [Great Buddha], Nōfuku-ji Temple, Kobe, Japan, 1900. Gelatin silver print. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Lunn Gallery, 1980 (1980.1128.1)

Adolf de Meyer (American [born France], 1868–1946). View through the window of a garden, Japan, 1900. Platinum print, 5 7/16 x 8 in. (13.8 x 20.3 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, Mrs. Jackson Burke Gift, 1981 (1981.1010.3)

Adolf de Meyer (American [born France], 1868–1946). Ueno Tōshō-gū, Tokyo, Japan, 1900. Platinum print, 5 11/16 x 7 13/16 in. (14.5 x 19.8 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, Mrs. Jackson Burke Gift, 1981 (1981.1010.4)

Adolf de Meyer (American [born France], 1868–1946). Garden pool with waterlilies, 1900. Carbon print, 4 13/16 x 7 15/16 in. (12.2 x 20.1 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, Mrs. Jackson Burke Gift, 1981 (1981.1010.22)

Notes

[1] Quoted in Alexandra Anderson-Spivy, Of Passions and Tenderness: Portraits of Olga by Baron de Meyer, edited by G. Ray Hawinks (Marina del Rey, CA: Graystone Books, 1992).

[2] Quoted in Philippe Jullian, De Meyer, edited by Robert Brandau (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1976), 26–28.

Related Content

Quicksilver Brilliance: Adolf de Meyer Photographs is on view at The Met Fifth Ave through April 8, 2018.

For more on Adolf and Olga de Meyer, see Anne Ehrenkranz, A Singular Elegance: The Photographs of Baron Adolph de Meyer (San Francisco: Chronicle Books, 1994).