Apollo's Muse: The Moon in the Age of Photography, by Mia Fineman and Beth Saunders with an introduction by Tom Hanks, features 150 full-color illustrations and is available at The Met Store and MetPublications.

Just over fifty years ago, the world watched with bated breath as the first humans set foot on the moon. Apollo's Muse: The Moon in the Age of Photography, accompanying an exhibition at The Met Fifth Avenue on view through September 22, 2019, celebrates this important anniversary but also explores scientific and poetic representations of the moon from the seventeenth century to the present. A lyrical introduction to the catalogue by Tom Hanks, star of Apollo 13, delves into the universal fascination with representations of the cosmos and the ways in which space travel expands the limits of human vision. Authors Mia Fineman and Beth Saunders present a compelling history of art and the moon, including explorations of nineteenth-century efforts to map the lunar surface, whimsical fantasies of life on the moon, and the visual language of the Cold War Space Race.

I had the opportunity to speak with Mia Fineman about the book as well as the moon's historic and ongoing role in politics, human imagination, science, and the history of art.

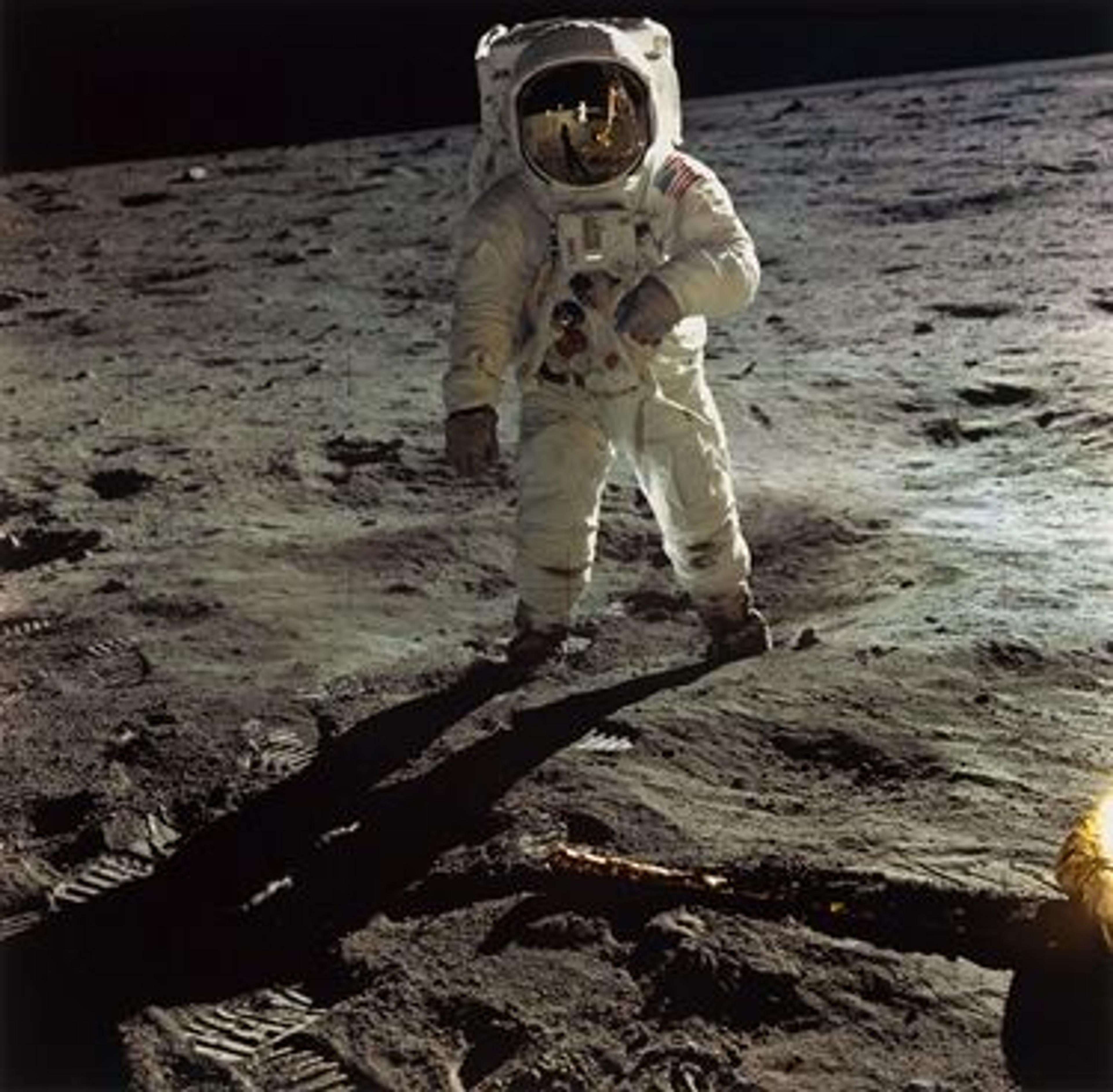

Neil Armstrong (NASA Apollo 11), Buzz Aldrin Walking on the Surface of the Moon near a Leg of the Lunar Module, 1969, printed later. Dye transfer print, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Purchase, Alfred Stieglitz Society Gifts, 2017 (2017.421).

Rachel High: Apollo's Muse coincides with the fiftieth anniversary of the moon landing. In a chapter of the book entitled "Moonshot," you outline the fascinating political impact of photography during the Space Race. What role did lunar photography play in this conflict?

Mia Fineman: The Space Race was part of the Cold War, which was a battle for political and technological supremacy between the United States and the Soviet Union. The Cold War really began after World War II when the balance of world power shifted. Both sides were afraid that whoever got to the moon first could send missiles from the moon down to Earth. This turned out not to be a likely scenario, but perhaps a more realistic fear at the time was that any nation that had the rocket power to get to the moon would also be able to direct an intercontinental ballistic missile at the enemy.

Photography played a role in this conflict in two different ways. One was as propaganda for both space programs. Soviet propaganda was more centralized and controlled by the government. The Soviet program strictly restricted access to most material and to the cosmonauts themselves. Records of technology were especially close guarded because the government feared they would lose military secrets to the other side.

The propaganda for the U.S. space program was not as closely controlled because the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) was an open agency based on transparency, at least to a degree. The American public paid for this program through their tax dollars, so NASA needed voters to be on board. The agency worked with different media including TV stations, newspapers, and magazines to publicize the space program and get people interested in human space flight.

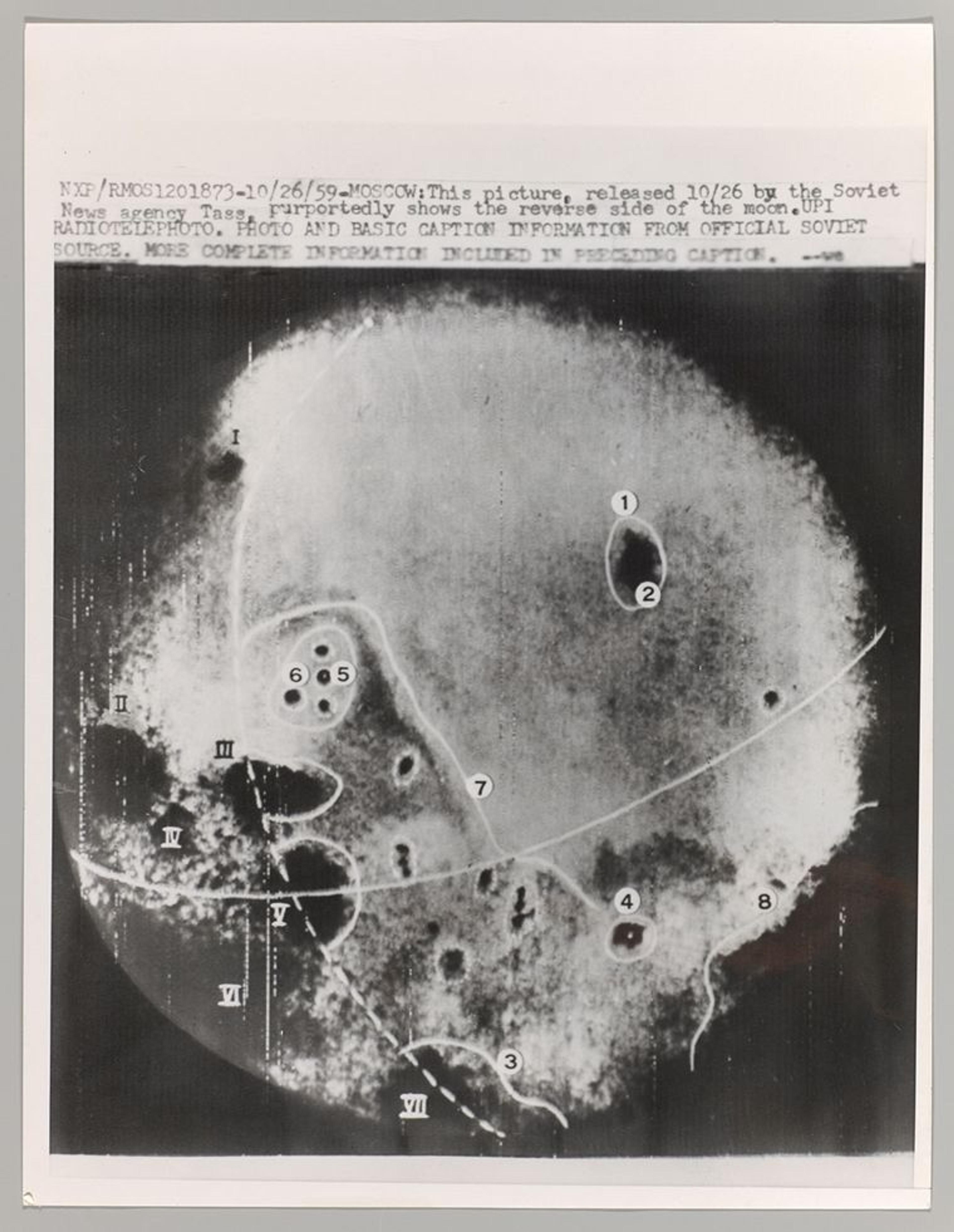

TASS (Telegraph Agency of the Soviet Union) USSR Luna 3, The Far Side of the Moon, 1959, Distributed by United Press International. Gelatin silver print. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Gift of Mary and Dan Solomon, 2016 (2016.796.1).

Apart from propagandistic images, photography also provided scientific views of the lunar surface, which allowed for a better understanding of the topography of the moon. Before humans set foot on the moon, robotic crewless missions photographed it—either by landing on the moon's surface or orbiting around it—and beamed the images back to Earth via radio waves. Both sides were using photographic imaging in the 1960s to help determine viable landing sites for their spacecraft.

Rachel High: One of the most compelling aspects of this catalogue—when compared with other books related to the Apollo mission coming out this year—is the inclusion of both scientific and creative accounts of the moon. In your essay, "Daydreams by Moonlight," you write that "the study of the moon has mingled observation and imagination." How did artists and photographers throughout history blur the lines between fantasy and fact?

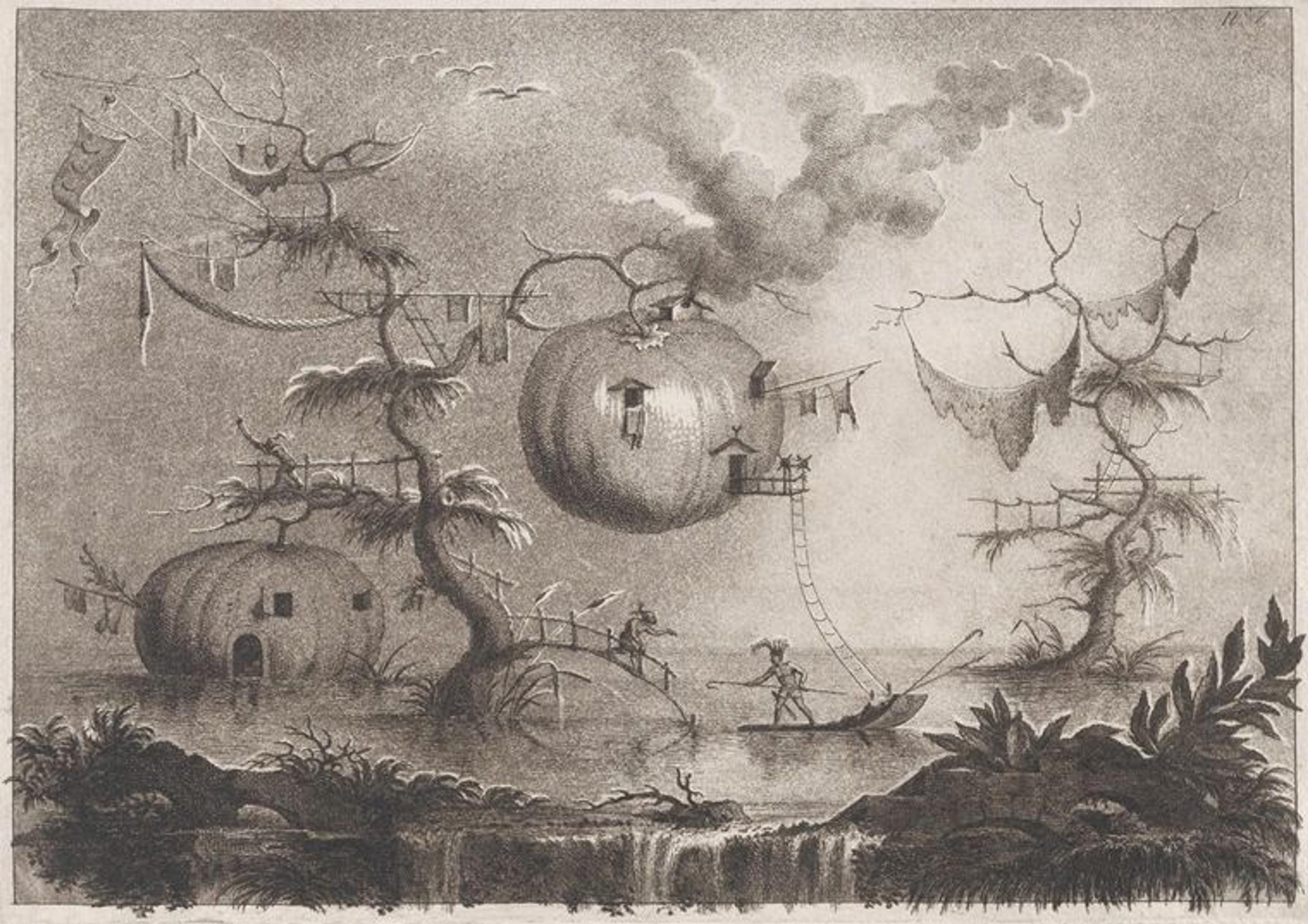

Mia Fineman: As soon as Galileo published the first views of the moon seen through a telescope, people began speculating about life on the moon. The book and exhibition feature an eighteenth-century print that shows one version of life on the moon as imagined by the artist. In the print, lunar inhabitants resemble depictions of Native Americans and are surrounded by flora and fauna associated with the Americas. Moon people are shown living in giant pumpkins and hunting oversized possums, the smaller versions of which are indigenous to the New World. The similarities between depictions of these two territories previously unknown to Europeans are no coincidence, and they emphasize the way artists use the moon to reflect the anxieties, preoccupations, and fantasies of the times.

Filippo Morghen (Italian, Florence 1730–after 1807 Naples). Pumpkins Used as Dwellings to Secure against Wild Beasts, from The Collection of the Most Notable Things Seen by John Wilkins, Erudite English Bishop, on His Famous Trip from the Earth to the Moon, 1766–67. Etching and aquatint. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Harris Brisbane Dick Fund, 1932 (32.74.8).

Fantasies of life on the moon continued well into the twentieth century, when photographs showed it to be a barren, dry, dusty place with no life. People speculated that there might be life on the far side of the moon (which never faces Earth) or in tunnels underground that we couldn't see. The public really didn't want to let go of the idea. In fact, there continues to be science fiction about life on the moon.

Before working on the project, I didn't realize how closely science and science fiction were connected. One of the things I learned was that all of the early rocket scientists were avid readers of science fiction. Jules Verne's novels inspired many scientists to create the technology that was envisioned in his books. Likewise, science fiction writers were studying the latest technology in order to add an element of believability to their fictions.

Rachel High: In the book, Beth Saunders writes on Rauschenberg's involvement in NASA Artists' Cooperation Program (established in 1962), Bell Labs' help in creating The Moon Museum, and works inspired by the moon made after the first lunar landing up to the present day. NASA has announced that it plans to send American astronauts back to the moon within the next five years. What are your thoughts about the future of art and photography with regards to its explorations of moons both real and imagined?

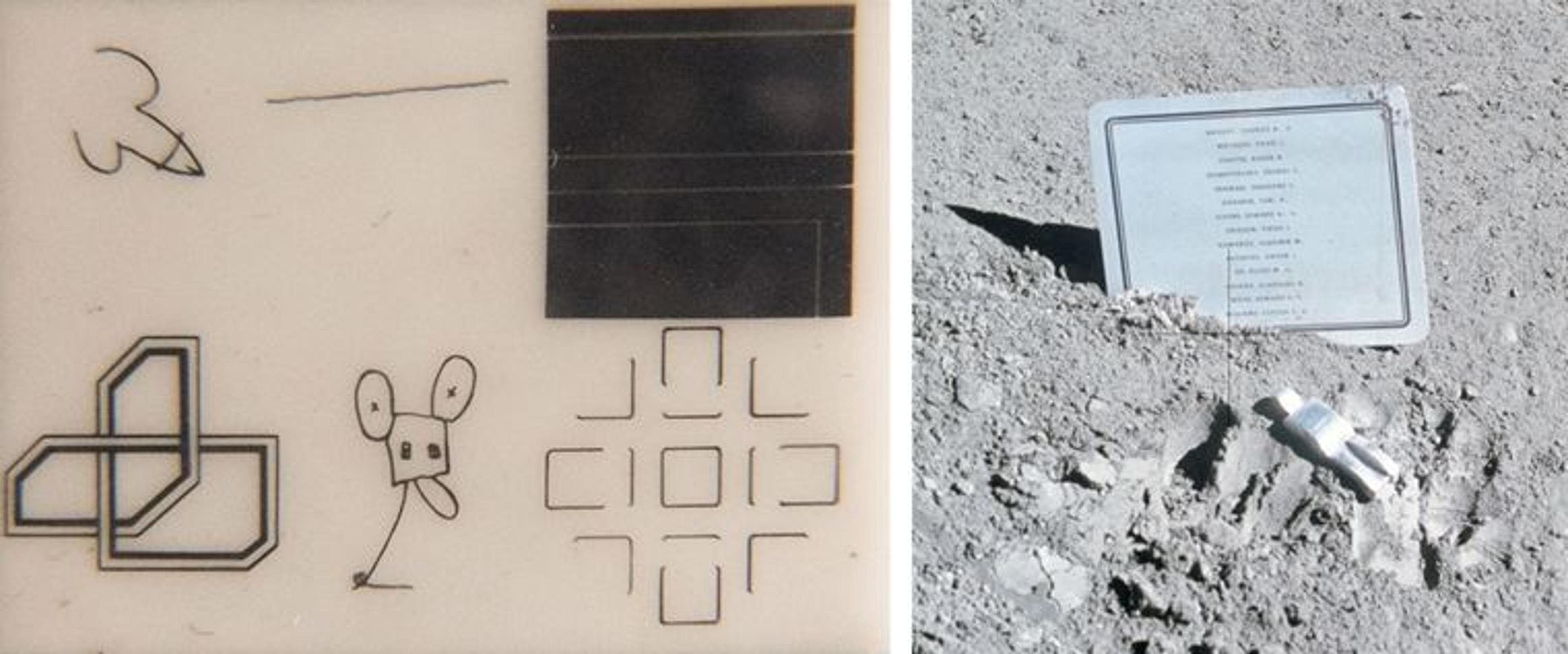

Mia Fineman: The Moon Museum, which consisted of minuscule works by John Chamberlain, Forrest Myers, David Novros, Claes Oldenburg, Robert Rauschenberg, and Andy Warhol, was sent secretly. The artists worked with someone involved in NASA to sneak it into one of the cargo carriers. Another artwork on the moon, Fallen Astronaut by Paul Van Hoeydonck was carried to the moon by astronaut David Scott.

Left: John Chamberlain, Forrest Myers, David Novros, Claes Oldenburg, Robert Rauschenberg, and Andy Warhol, The Moon Museum, 1969. Lithograph of tantalum nitride on ceramic wafer, Collection of Forrest W. Myers. Right: David Scott (NASA Apollo 15), Paul van Hoeydonck's "Fallen Astronaut" Sculpture on the Lunar Surface, 1971, printed 2019. Inkjet exhibition print from digital file.

Our story of scientific lunar photography ends in 1969. Of course, important lunar photography is going on today. The photographs made by a Chinese spacecraft of the far side of the moon are one example. There is also almost an infinite amount of contemporary art about the moon today, which we discovered over the course of our research.

NASA still does work with artists, and I think that artists will definitely want to send more art to the moon, or beyond. If commercial flights to the moon become available, many more artists will be creating works, and there really will be a museum on the moon, which would be a cool outpost to visit.

Rachel High: "The Met Moon!"

Mia Fineman: Exactly! As a joke, I considered applying for a research travel grant to go to the moon, but I never actually wrote out the application. Someday that won't sound as absurd as it does today.