Franz Michael Diespach (before 1725–ca. 1791), incorporating pieces by Jean Jacques Pallard (1701–1776). Hat Ornament with the "Dresden Green" from the Diamond Garniture (detail), Dresden and Prague, 1769; older elements Vienna, 1746. Almond-shaped celadon-green diamond of 160 grains (approx. 41 carats); two round, brilliant-cut diamonds, one of 24 1/2 grains (approx. 6.28 carats), the other of unknown weight; 411 medium to small diamonds; silver; gold, 5 1/2 x 2 in. (14.1 x 5 cm). Grünes Gewölbe, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden (VIII 30)

Jewelry in eighteenth-century Europe was more than mere ornamentation; it was an effective means of attracting the attention and respect of one's peers. Ornamenting the body with jewelry sets, or garnitures, of sapphire, ruby, jacinth, and diamonds not only communicated wealth, but also shrouded the wearer in the symbolic meanings attached to such precious stones.

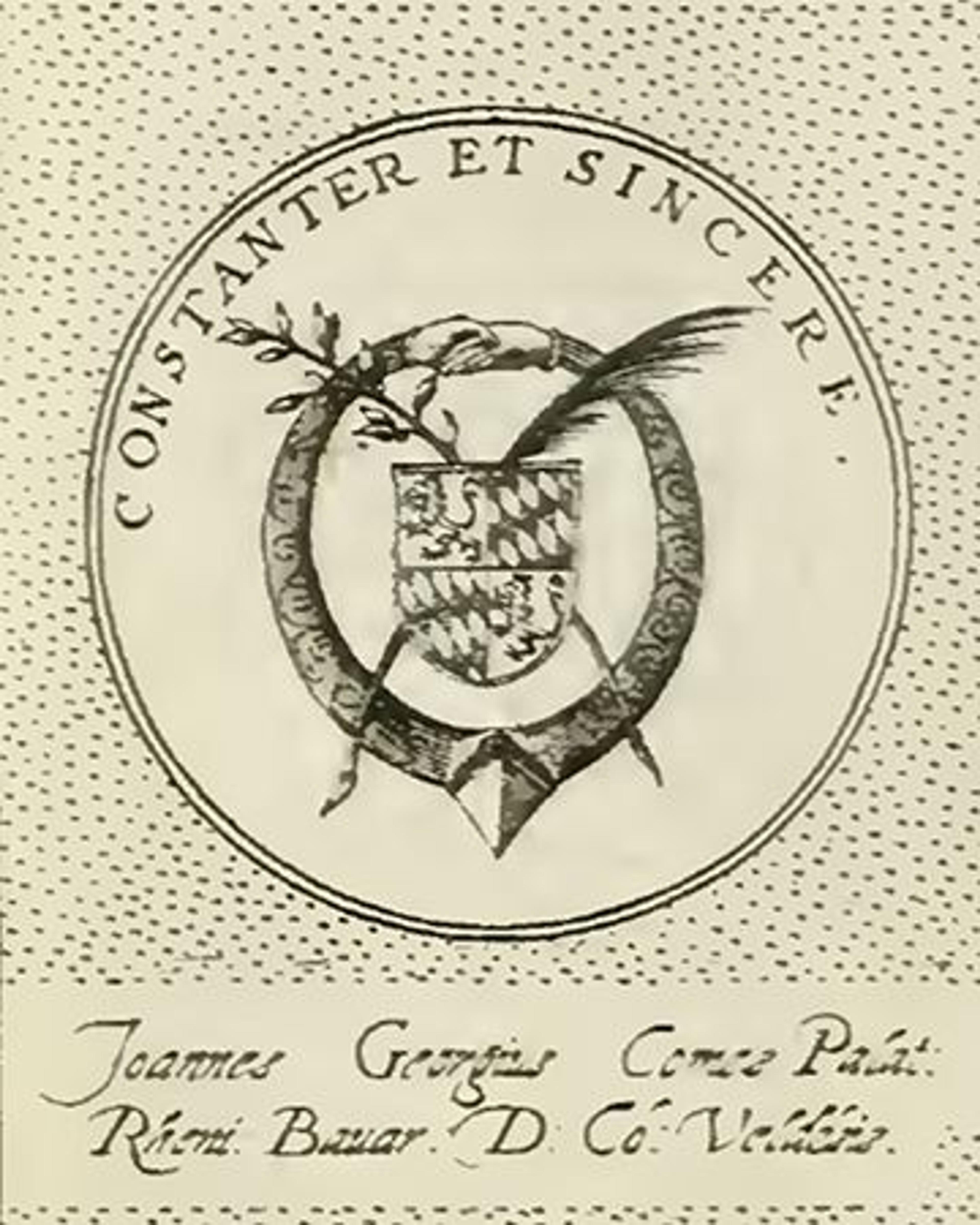

Europeans have long associated diamonds with the virtues of purity and steadfastness, because of their clarity and hardness (the word "adamant" stems from the same Latin root as "diamond"). As early as the sixteenth century, rulers in the German provinces incorporated the stones into their insignia; Count Palatine and Duke of Bavaria Johann Casimir, for example, incorporated a ring set with a point-cut diamond into his impresa, below. Even his motto, constanter et sincere, references the virtues associated with the stone. In the case of the "Dresden Green" diamond—one of the rarest gemstones in the world and, at 41 carats (160 grains), the largest natural green diamond known today—the gemstone has become a symbol of the constancy of Saxon rule.

Right: Impresa of Johan Casimir, Count Palatine and Duke of Bavaria. From Jacopus Typot (ca. 1540–ca. 1600), Symbola varia Diversorum Principum Sacrosanc Ecclesiae & sacri Imperij Romani (Amsterdam: Ysbrandus Haring, 1686). Engraving, 5 3/16 x 3 1/8 x 1 3/8 in. (13.1 x 8 x 3.5 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, Harris Brisbane Dick Fund, 1945 (45.69). Image (detail) courtesy Internet Archive

Currently exhibited in Making Marvels: Science and Splendor at the Courts of Europe, the Dresden Green has an enchanting, evenly distributed color—an extremely rare trait in natural green diamonds. The hue was produced by a natural source of ionizing radiation within the earth's crust, most likely generated by the decay of uranium, thorium, or potassium. In addition to its color, the stone's composition gives it a high grade of clarity and its lack of nitrogen and boron impurities makes it almost entirely flawless.

The Dresden Green has been a focal point of the Saxon electors' collection since 1741. Most likely mined in the Golconda region of India, the diamond's presence in Dresden was first referenced in an inventory record noting its purchase by Friedrich Augustus II—elector of Saxony, king of Poland (as Augustus III), and grand duke of Lithuania (a descendant of Johann Casimir by marriage)—from a London merchant called Delles. Though there is no official record of the final sum, rumor had spread even one year after the sale. Frederick II of Prussia (known as Frederick the Great) wrote in a letter that "for the siege of Brünn [the capital of Moravia] the king of Poland was asked for heavy artillery. He refused due to the scarcity of money; he had just spent 400,000 thaler for a large green diamond." At the time, the exorbitant sum would have been worth about four tons of gold. When Delles sold the diamond to Augustus II, the diamond had already been cut, and the stone retains this original form today. The craftsman modified a pear-shaped brilliant cut, which left the diamond very thick in the center, to accentuate its unusual coloration.

Left: In this portrait, King Augustus III wears a badge of the Order of the Golden Fleece, likely the Yellow Topaz Golden Fleece (VIII 5 ). Pietro Antonio Rotari (Italian, 1701–1762). King Augustus III of Poland, 1755. Oil on canvas, 108 x 86 cm. Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden (99/77). Public-domain image via Wikimedia Commons

It is clear that Augustus II appreciated the uniqueness of the stone, as only a year later he commissioned court jeweler Johann Friedrich Dinglinger to incorporate it into a badge of the Order of the Golden Fleece, then the most important chivalric order in Europe. The order was restricted to Catholic princes and other noblemen, to whom the order's badge contributed great stature. As a member, Augustus II was authorized to commission jeweled versions of the order's insignia, which includes a ram's skin hung from gathered flames.

Even when Augustus II grew tired of Dinglinger's setting, the Dresden Green remained a central element of the elector's collection of Golden Fleece gems. In 1746, only four years after Dinglinger finished his badge, Augustus II had it dismantled and the diamond incorporated into a different setting. This second badge of the Order of the Golden Fleece was commissioned from Geneva goldsmith André Jacques Pallard in Vienna. It included not only the Dresden Green, but also the so-called "Saxon White" diamond, the largest of Augustus II's white diamonds at the time (about 49 carats). Both stones remained in this second Fleece badge for over twenty years—it was Augustus II's favorite Golden Fleece jewel to wear during state festivals, and he even sent it to Königstein Fortress to keep it safe during the Seven Years' War.

After the death of both Augustus II and his son, Friedrich Christian, in 1763, the jewelry collection of the Saxon electors, including Pallard's Golden Fleece, passed to Augustus II's thirteen-year-old grandson, Friedrich Augustus. Friedrich Augustus left the diamond in Pallard's Golden Fleece badge until 1768, when he reached the age of majority and had it transformed into a more fashionable piece, which he commissioned from Prague jeweler Franz Michael Diespach. Diespach did not completely dismantle Pallard's Golden Fleece; the flames from which the ram's fleece hung were largely destroyed, but the three larger elements (the crowning coulant, the central flint, and the dangling fleece) were kept intact and incorporated into three other jewels.

The "Dresden Green" diamond set in a hat ornament designed by Franz Michael Diespach, with elements by André Jacques Pallard. Grünes Gewölbe, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden (VIII 30)

The Brilliant Garniture, Grünes Gewölbe (Green Vault). Image courtesy BPK Bildagentur / Staatliche Kunstsammlungen, Dresden / Art Resource, NY

The green diamond is still mounted in the flint of Pallard's Golden Fleece badge. Diespach kept Pallard's setting—which, in addition to the green diamond, holds several brilliant-cut white diamonds—and used it as the dominant component of a complex hat ornament. The jeweler fashioned the rest of the ornament as two intertwining ribbons set with old-mine-cut diamonds that culminate in a bow, at the center of which is a large antique-cut diamond. The bow topping the ornament is backed with a clasp. Pallard's riotous setting for the Dresden Green retains some Rococo spirit, while the composition of Diespach's intertwining ribbons, with their more sober, regularly set diamonds, looks more to the Neoclassical style of the Enlightenment era.

Diespach's hat ornament, in which the green diamond remains today, is part of the "Brilliant Garniture," one of two large diamond garnitures in the Saxon collection named for the respective cuts of the diamonds used in their components (the other is called the "Rose Garniture").

The importance of the Dresden Green to the Saxon electors is clear, but they were not the only ones to value the stone. Admiration for the Dresden Green has been widespread since it first came on the market in 1726. In 1753, the British Museum of Natural History acquired the bulk of the collection of British collector Sir Hans Sloane. Among many other treasures, Sloane at some point acquired a glass model of the Dresden Green, which remains in the museum's collection as a testament to the stone's enduring allure.

Today, the real Dresden Green is displayed in the historic Green Vault of the Staatliche Kunstsammlunge, Dresden, as part of the Saxon electors' jewelry collection, to which it attracts visitors from around the world. Though its ownership has passed from elector to elector, and with each of their tastes the design of its setting has changed, the Dresden Green has always remained one of the true prizes of the Saxon treasury. It is currently on view inMaking Marvels in gallery 999, through March 1, 2020.

Related Content

Making Marvels: Science and Splendor in the Courts of Europe is on view at The Met Fifth Avenue through March 1, 2020.