Gerhard Richter: Painting After All, by Sheena Wagstaff and Benjamin H. D. Buchloh, with essays by Briony Fer, Hal Foster, Peter Geimer, Brinda Kumar, and André Rottmann, featuring 268 full-color illustrations, is available at The Met Store and MetPublications. The catalogue is made possible by the Mary C. and James W. Fosburgh Publications Fund. Additional support is provided by Christie's, and by Sharon Wee and Tracy Fu.

Throughout his acclaimed sixty-year career, Gerhard Richter (German, b. 1932) has employed both representation and abstraction as a means of reckoning with personal history, collective memory, and identity, particularly in the context of post–World War II German society. The book Gerhard Richter: Painting After All accompanies the culminating exhibition at The Met Breuer and is the first major presentation of the artist's work in the United States in nearly two decades. The catalogue addresses several aspects of Richter's varied oeuvre and includes essays by leading experts on the artist. While illuminating Richter's preoccupation with painting in relation to other modes of representation, the book also emphasizes the ongoing importance of the medium in contemporary art.

I spoke with curators Sheena Wagstaff and Brinda Kumar from The Met's Department of Modern and Contemporary Art about Richter's engagement with painterly tradition, his relationship to photography, and the reasons why the artist's work is increasingly relevant today.

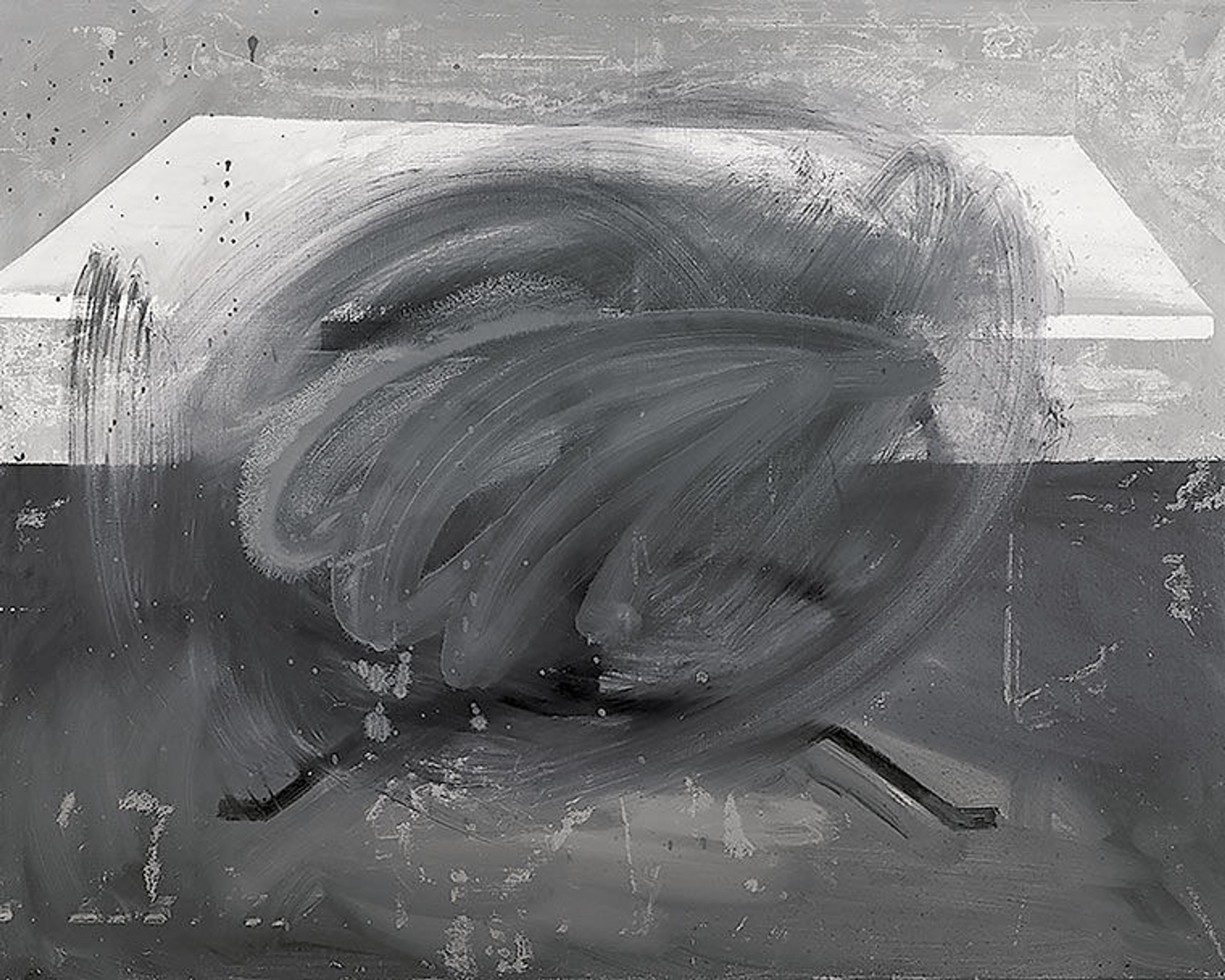

Rachel High: Many artists and critics have announced the death of painting over the years, but the medium has always been at the center of Richter's practice. The subtitle of the show and the catalogue, "Painting After All," suggests that painting has endured despite certain forces working against it. How does this subtitle capture the role of painting in Richter's work?

Sheena Wagstaff: Richter came up with the title himself. It is a nuanced phrase with several different meanings. It could denote the endurance of painting, but one of the topics that we cover in the exhibition and catalogue is painting's ability to confront historic memory and instances of collective and personal trauma. In this context, the title is ultimately a question: Is painting able to deal with those universal notions or is it, after all, only painting?

There's another meaning that has an air of resignation to it: After everything that has happened to humankind, painting remains. After everything we have experienced, painting is still there as evidence of our collective endurance, even as our individual lives come to an end. It is perhaps a comment on the artist's awareness of his own mortality, as well as our own.

Finally, Richter's iterations in different media—including printmaking, photograph, new technology, even glass sculpture—are in the end, all about painting. Painting, after all.

Installation view: Gerhard Richter's Birkenau series, 2014. Each: oil on canvas, 8 ft. 6 3/8 in. x 78 3/4 in. (260 x 200 cm). Private Collection. © Gerhard Richter 2020 (20012020).

Brinda Kumar: The title specifically resonates with one series at the heart of the exhibition: the Birkenau cycle. Birkenau was based on photographs discussed in Images in Spite of All (2003), a book by French art historian Georges Didi-Huberman. The exhibition's subtitle can signify "in spite of all," "after all," or even "above all," depending on how it is interpreted, which suggests there is also a more oblique connection to the question of translation.

In fact, translation is an essential part of Richter's artistic project. For example, Richter calls his works "abstract paintings," but in German, they are abstrakte bilder. "Bilder" can mean both pictures and paintings. Fittingly, painting's relationship to pictures is something that Richter explores through his practice as well.

Sheena Wagstaff: A picture and a painting are actually quite distinct entities, and yet one image can be both.

Rachel High: It is interesting to connect that notion of picture versus painting to the recent book and exhibition, Photography's Last Century, organized by The Met's Department of Photographs. Photography's Last Century discusses changes in the medium throughout the twentieth century, from photography gaining recognition as an art form in its own right to the transition from film to digital imaging. Richter experienced the ideological and technological changes in photography first-hand during his six-decade-long career. How has his understanding of and engagement with photography changed as this medium has evolved?

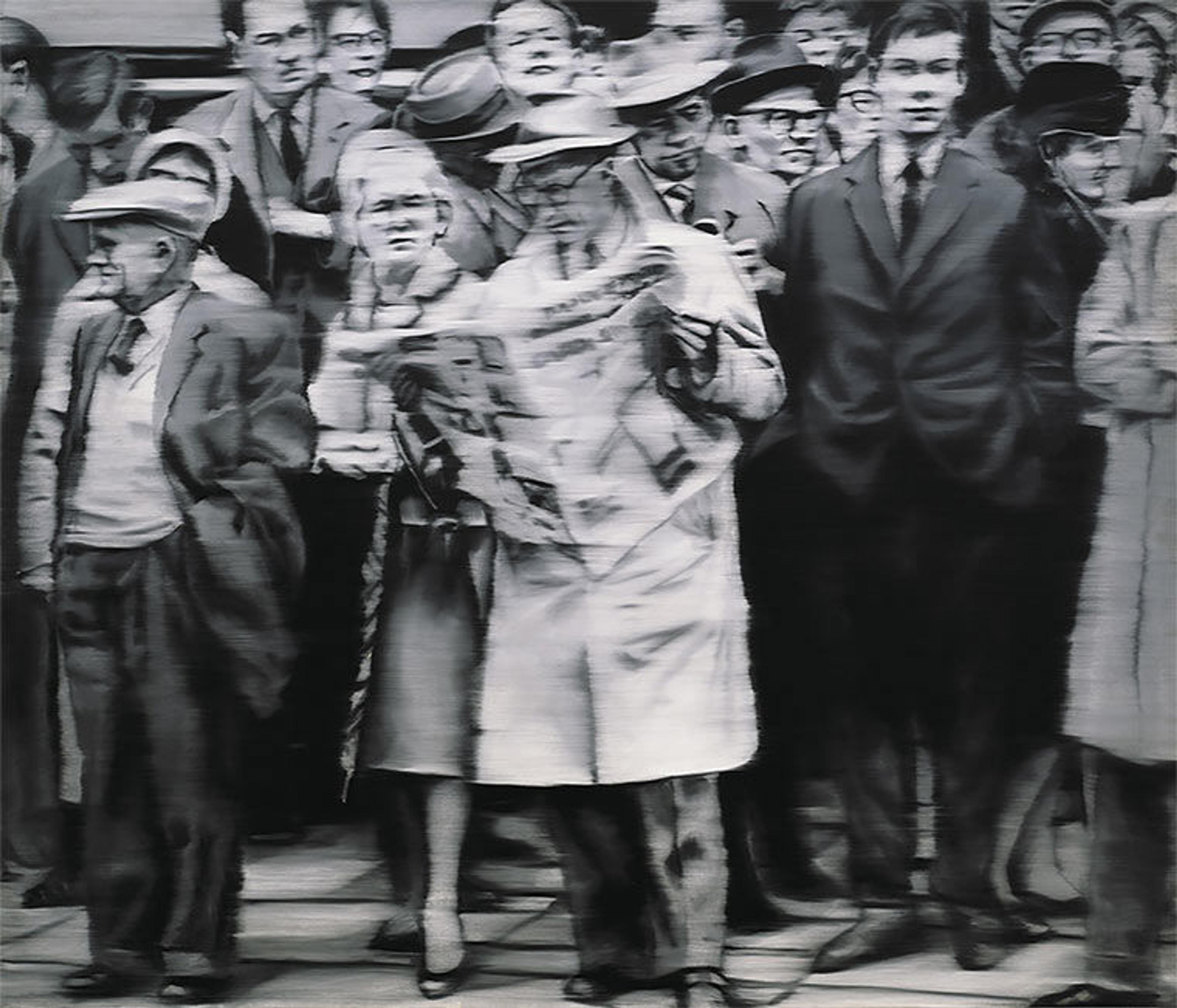

Gerhard Richter (German, b. 1932). Group of People, 1965. Oil on canvas, 66 15/16 x 78 3/4 in. (170 x 200 cm). Private Collection. © Gerhard Richter 2020 (20012020).

Gerhard Richter (German, b. 1932). Betty, 1977. Oil on wood, 11 13/16 x 15 3/4 in. (30 x 40 cm). Museum Ludwig, Cologne / Loan from private collection 2007. © Gerhard Richter 2020 (20012020)

Brinda Kumar: Richter is interested in what photography affords as a medium. His earliest paintings—his breakthrough works following his defection to West Germany in 1961—were his photo paintings. These works were based on photographs, but the paintings removed the images from the specific context in which they were meant to be encountered.

For example, some of the photographs Richter used were meant to be seen in reproduction, such as in the media culture of newspapers and magazines. But he also addressed a more personal, intimate relationship with photography, through family picture albums, which are not typically in wide circulation.

Sheena Wagstaff: Richter has always embraced photography as a source for his art, but paradoxically, he has also used it as a foil to painting, because of his deep-seated mistrust of photography's supposed ability to depict or capture a sense of realism.

Brinda Kumar: Richter collected a number of the photographs that he found or took himself in a compendium known as the Atlas. This was not just a collection of source imagery, but also spaces where he could experiment. As Richter has said about his approach to landscape paintings, "I see countless landscapes, photograph barely 1 in 100,000, and paint barely 1 in 100 of those that I photograph." He looks at photography somewhat askance, both as a vector for memory and also as a reflection of reality.

Gerhard Richter (German, b. 1932). Atlas sheet 222, "Rooms" (detail), 1970. 20 3/8 x 14 1/2 in. (51.7 x 36.7 cm). © Gerhard Richter 2020 (20012020).

Sheena Wagstaff: A reflection of reality, but one that is ultimately not about truth in any direct way.

Rachel High: Sheena, in your introduction to the catalogue, you establish Table (1962) and September (2005) as focal points of Richter's work. The exhibition opens with these two paintings, as well as the glass work 11 Panes (2004). Why did you select these particular works to open the book and exhibition?

Sheena Wagstaff: The works represent three approaches or indicative strands of the artist's practice that run through the catalogue and the exhibition.

Gerhard Richter (German, b. 1932). Table (Tisch), 1962. Oil on canvas, 35 7/16 x 44 1/2 in. (90 x 113 cm). Collection of Anne Simone Kleinman and Thomas Wong. © Gerhard Richter 2020 (20012020)

Gerhard Richter (German, b. 1932). September, 2005. 20 1/2 x 28 3/8 in. Oil on canvas, 20 1/2 x 28 3/8 in. (52 x 72 cm). The Museum of Modern Art, New York, Gift of the artist and Joe Hage, 2008. © Gerhard Richter 2020 (20012020)

Table is the first work in Richter's catalogue raisonné. He claimed that this was his first mature work, and he destroyed most of what had preceded it. Table was more experimental and a departure from his previous paintings because of its relationship to photography; the original source was a photograph of a modern table printed in a magazine. The painting is not a specious homage to photography, but an acknowledgment of photography's importance in the circulation of any image. The frantic scrubbing-out gesture also makes Table a disturbing picture, because it focuses our attention on that violent expression of eradication. It's as if that painterly action is destroying the photographic image as we watch!

The second image is one we all know so well. September was created four years after 9/11, and it has a particular resonance for New Yorkers, as well as the rest of the world. It is an image we witnessed almost at the instant of its impact. The image is fraught with a heavy symbolism and spectacular resonance. Due to its media ubiquity, it is instantly recognizable, and its function of marking an event in time has become very complicated—emotionally, sociologically, and politically. Richter was flying to New York at the time of the attack, and his personal experience may have provoked his long-considered attempt to render that moment in a modestly scaled amalgam of photographic and painterly image.

Left: Diego Velázquez (Spanish, 1599–1660). Las Meninas, 1656. Oil on canvas, 126 1/4 x 110 7/8 in. (320.5 x 281.5 cm). Museo del Prado, Madrid (P001174).

Richter's glass and mirror works are more important than they have been given credence to to-date. These works engage with a great pictorial tradition that was employed by everyone from Velázquez and Titian, all the way through to Barnett Newman and Kerry James Marshall. Our relationship to painting and reflection allows us to see ourselves implicated within the pictorial space of a work of art. Richter's mirrors take this to its logical conclusion, as our image appears iterated or reflected within the physical environment in which Richter's glass pieces are displayed.

Ultimately, Richter's work is about pictorial and painterly traditions. Standing in front of a painting has more of a singular presence and relevance to our actual living moment than photography will ever have, because photography always marks the instant of passing—the death—of the very moment it records. It is this paradox, burrowed deep in Richter's work, that enables the image to continue to live, to be relevant.

Installation view: Gerhard Richter (German, b. 1932). Gray Mirror (4 Parts) (Grauer Spiegel [4 Teile]), 2018. Lacquer on back of glass, 89 3/4 in. x 29 ft. 11 1/16 in. (228 x 912 cm). Private collection. © Gerhard Richter 2020 (20012020)

Rachel High: This is the final exhibition at The Met Breuer and the first major exhibition of Richter's work in the United States in nearly twenty years. Why is it important to look at Richter anew, and how do the book and exhibition speak to The Met's commitment to contemporary art going forward?

Sheena Wagstaff: There are a number of answers to those questions. The Breuer program has made a concerted effort to take account of different types of histories that are perhaps not so well known in the United States. We have also cast a fresh look on artists whose work we think we already know—like Edvard Munch, Marsden Hartley, or even Vija Celmins, a peer of Gerhard Richter.

We also mounted experimental thematic exhibitions. Unfinished (2016) and Like Life (2018) are both good examples of the type of shows that exemplify modern and contemporary art's deep connection to the history of art.

Brinda Kumar: Gerhard Richter: Painting After All continues this investigation into both thematic approaches and deep dives into artists' careers. Richter's oeuvre epitomizes the continuous examination of the possibilities of art, and in his case, of painting. We have the extraordinary opportunity to introduce or reintroduce his works to newer generations, including younger generations of painters. Richter, as the book and exhibition demonstrate, has been prolific in the last two decades. The two series at the heart of the exhibition—Cage (2006) and Birkenau (2014)—date from this period. This is an opportunity to take account of a full career and share it widely with a specific focus.

Sheena Wagstaff: Richter is an artist who has an extraordinary facility for both abstraction and pictorial realism. He has reinvented that medium time and again. Yes, he is well known, but the commodification of his work—about which he despairs—has been so manipulated by the market that it has completely obscured the truly remarkable scope of his artistic project. His work has importance not just to now, but to the entire century, and to the greater world history of art.

In the last five to ten years, other artists—including Henry Taylor, Etel Adnan, Cecily Brown, Julie Mehretu, Jordan Casteel and Dana Schutz—have newly acknowledged the importance of painting. These artists, among many others, look to Richter. They may not follow directly in his footsteps, but his status as a benchmark artist who is in his prime right now is undeniable. We hope that both the exhibition and catalogue offer an exquisite encounter with a formidable master.

Related Content

Tour the exhibition galleries of Gerhard Richter: Painting After All in this video and see more of the works on view.

Get an inside look at a master painter at work in Gerhard Richter Painting, a feature-length documentary streaming at The Met for a limited time.

In 2020 art can be made from literally anything. So why still paint? Gerhard Richter has some answers. Check out the Primer.