During World War II, Met staff worked tirelessly to keep the Museum's doors open throughout the war. Above is a gallery view of the exhibition Artists for Victory, which ran from December 7, 1942–February 22, 1943.

In a spectacularly organized campaign, The Met transported thousands of irreplaceable artworks out of New York City for safekeeping during World War II. Although this initiative has become a largely forgotten part of the Museum’s wartime history, Met staff were responsible for one of the most complex art evacuations in American history. They accomplished this incredible feat despite maintaining an active exhibition program throughout the war that, even with thousands of works stored offsite in 1942, also resulted in the greatest attendance since the founding of the institution in 1870.

The protection of The Met collection, staff, and visitors became a priority within weeks of Hitler’s declaration of war against the U.S. on December 11, 1941. All Museum buildings closed at dusk, additional equipment for fire protection was immediately ordered, and air raid drills were provided to the staff. New Yorkers were particularly worried about air raids, as Reichsmarschall Hermann Göring had ordered the German aircraft industry to produce a plane capable of carrying a five-ton bomb to New York. A false air raid alarm sent more than two hundred fighter planes into the air on December 9, 1941, causing the emergency evacuation of the Museum. Each night, a member of the senior staff slept at the Museum alongside a cadre of armed guards.

Experience in England had already shown that museums were not immune to attack by enemy forces. Met Director Francis Henry Taylor and his administration looked to their English colleagues for advice on the best ways to protect the collection onsite and the potential need to remove parts of the collection to safety. As there had been during World War I, Museum officials were greatly concerned about the five-and-a-half acres of skylights over the second-floor paintings galleries, which created a huge target for potential enemy bombers with the light it emitted.

A 1931 aerial photograph showing the Museum's five-and-a-half acres of light-emitting skylights, which made the building a potential target for enemy bombers.

The Cloisters, The Met’s branch location devoted to the art of the late medieval period, which had only opened in 1938, was of particular concern given its location in Fort Tryon Park where it occupied the highest ground on Manhattan Island. The likelihood of anti-aircraft batteries being set up in the park, which commanded approaches to important bridges into the city, caused Met staff to immediately remove the famed Unicorn tapestries from display. In addition, regular window glass replaced the medieval stained glass on display in order to minimize the threat of damage to artworks by exploding anti-aircraft shells.

In the meantime, Francis Henry Taylor; William Church Osborn, the Museum’s president; and members of the Board of Trustees considered various courses of action to protect the entire collection. They decided that it was necessary to create a bombproof storage shelter under the Museum or offsite and by July 1940, an area of the sub-basement of the Museum was identified as a suitable location. Twenty-six feet wide, ten feet high, and four city blocks long, this space was a section of brick tunneling associated with the Croton Aqueduct, a water distribution system constructed for New York City in the nineteenth century. To create such a space, however, required the approval of Robert Moses, New York City Parks Commissioner, who expressed opposition to the plan. Instead, like the National Gallery in London, which sent works of art to storage at a mine in the Welsh countryside, The Met initially leased an abandoned mine located about sixty miles north of New York City. Unfortunately, conditions inside the mine proved too damp for art storage.

Museum staff continued to investigate warehouses, country houses, and vaults in Manhattan, the Bronx, and to the north of the city; in all, more than fifty locations were reviewed across New England. By mid-January 1942, just weeks after the United States officially entered World War II, the Museum signed a lease on Whitemarsh Hall, a fireproof country house constructed of steel and concrete located on several hundred acres of countryside on a hill just fifteen miles outside of Philadelphia.

The fireproof country estate Whitemarsh Hall, just fifteen miles outside Philadelphia, where many works from The Met collection were kept during World War II.

Begun in 1916, the six-story Georgian-style estate—which boasted 147 rooms across three floors above ground and three floors below—was built for the self-made banking millionaire, Edward Stotesbury. By 1932, the family had abandoned the estate due to financial hardship. Given the ideal conditions at the estate, Whitemarsh Hall became the refuge of The Met’s most irreplaceable works of art during World War II.

In devising a system to identify and pack artworks slated for removal and shipping them to the estate, Met officials once again looked across the Atlantic to the experience of English museums. With more than a half a million works of art in The Met collection, staff classified artworks with an “A-B-C” system. Works of art identified with an “A” were thought to be unique and of irreplaceable quality; they were evacuated first. Those objects designated with the letter “B” were to be moved later, and those identified with a “C” were to remain in the building either on display or in storage. Each department was tasked with creating lists of artworks: the first consisted of the fifty most important works, followed by a list of three hundred works to be protected after the first group had been removed from the building.

Ninety truckloads of art were transported to Whitemarsh Hall in 1942. Anthony van Dyck's portrait of John Stuart is seen here in transit.

More than fifteen thousand artworks from the Museum’s permanent collection traveled to Whitemarsh Hall in 1942, from the first shipment, which arrived on February 9, through May 1942. Ninety separate truckloads insured at one million dollars each were transported via truck accompanied by armed men. Fortunately, a series of photographs taken in 1944 show us the estate, select works of art, and Museum staff working there during this period. A continuous steel-mesh-and-barbed-wire fence surrounded the building.

A steel-mesh-and-barbed-wire fence surrounded the building, seen here, perhaps, with the watchdog named Peggy.

There were only two gates, both of which were kept locked at all times and the entire area could be flooded with light at a moment’s notice by searchlights installed on the roof. A watchdog named Peggy spent the night between the building and the fence and an hourly patrol of the entire building was made. Inside, a structure of steel pipes was built from which to hang paintings. When full, the room held 450 paintings hung in rows on racks from floor to ceiling. Crated and boxed works of art were stored in other rooms, including the basement, and the kitchen was fitted into a photographic and restoration laboratory.

Left: The structure made of steel pipes, from which paintings were hung in rows, from floor to ceiling. Right: The estate's kitchen was fitted into a photographic and restoration laboratory.

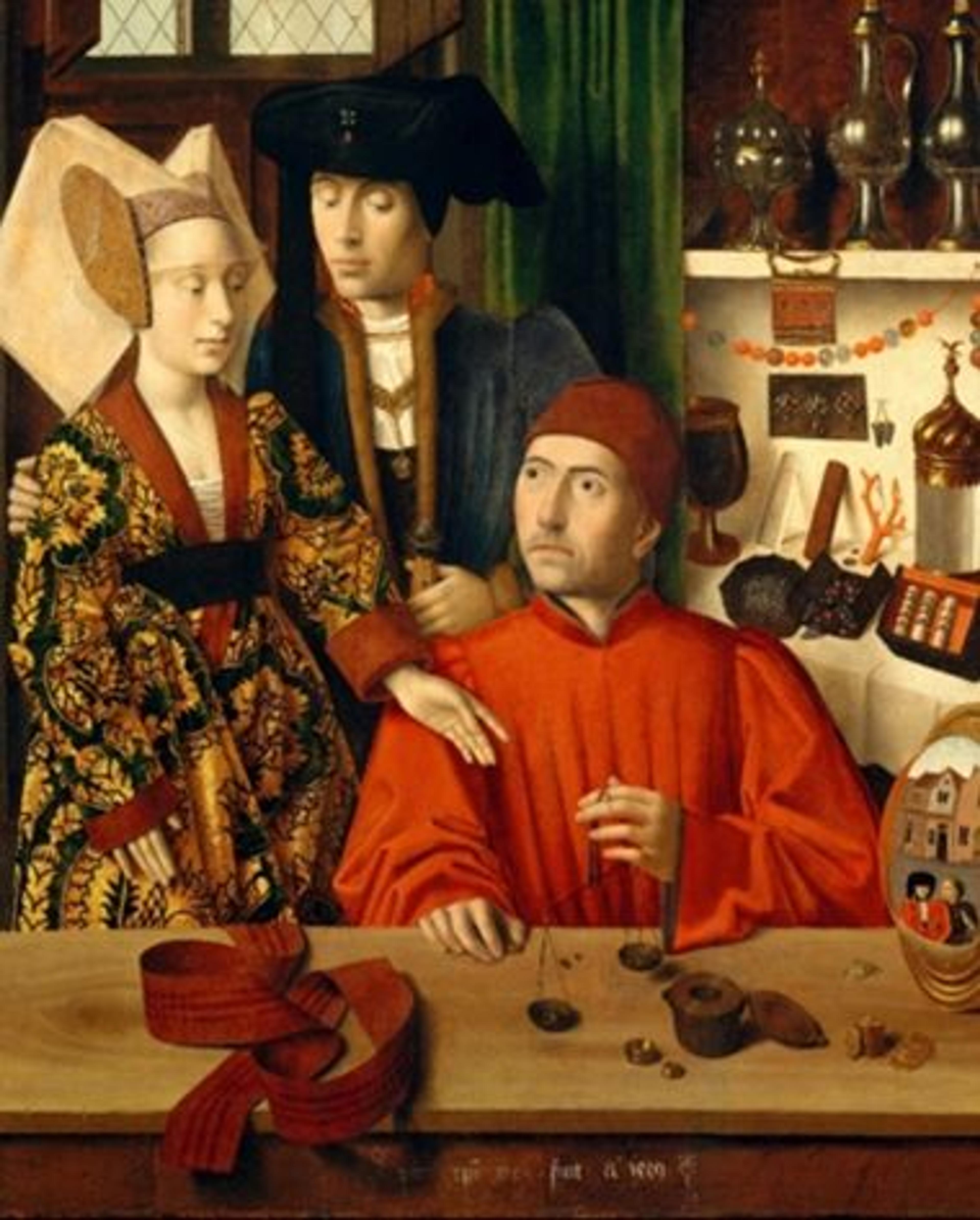

With only half of the fifty thousand cubic feet of space available at the estate in use by The Met, the Museum offered in January 1942 to store artworks belonging to other local institutions and private collectors, including the Brooklyn Museum, the City of New York, the Morgan Library, and many others. The painting A Goldsmith in his Shop by Petrus Christus, belonging to Robert Lehman and valued at $100,000, was among the works sent to the estate. Lehman bequeathed the painting to the Museum in 1975.

Right: Petrus Christus (Netherlandish, active 1444–1475/6). A Goldsmith in his Shop, 1449. Oil on oak panel, 39 3/8 x 33 3/4 in. (100.1 x 85.8 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Robert Lehman Collection, 1975 (1975.1.110)

Full-length portraits of the Marquis de Lafayette and George Washington were among the paintings stored by the City of New York. In total, the estate housed about 28,000 works of art. The transport was handled with such secrecy that no one knew what was happening, but neighborhood gossip included that it was used to confine Axis diplomats or was a mental hospital for soldiers. Despite efforts to keep this initiative confidential, the press published many articles focused on the Museum’s evacuation plans.

Even with a portion of The Met collection stored at Whitemarsh Hall, 1942 saw the largest attendance in the Museum’s history because of the large number of service men and women passing through New York. For this reason, and due to Allied military progress, a selection of one hundred paintings were returned for immediate exhibition in 1943. Later that year, Whitemarsh Hall was sold to the Pennsylvania Salt Manufacturing Company and The Met’s lease was terminated. The process of returning the collection to the Museum began in late 1943 and continued into 1944. On one return trip in February 1944, the Museum’s driver, whose name is recorded only as McMahon, was pulled over for speeding and fined twelve dollars for driving forty miles per hour.

Only five works of art stored offsite were identified as having sustained minimal damage, demonstrating the success of The Met’s initiative to remove its most important collections to safety. While The Met collection fared exceptionally well during the war, Whitemarsh Hall, sadly, later fell into disrepair. Despite efforts to preserve it, the estate was demolished in 1980 in favor of a housing development.

Less than five years after the end of World War II, the Museum was faced with the possibility of moving its collection offsite yet again. In response to hostilities in Korea and the beginning of the Cold War, works of art were sent to Colorado in the early 1950s; later, space was identified at the U.S. Mint at West Point for possible art storage. Met staff relied greatly on their efforts during World War II as a framework for these later activities.

Met staff and trustees acted decisively and methodically to safeguard the collection at a critical moment in world history, during a period that witnessed the largest wholesale destruction of art and cultural heritage in modern times. The record of their work documented in memos, lists, and photographs, attests to a keen sense of purpose in the face of adversity and in a shared commitment to the care of the collection for future generations. At the same moment, however, Met staff worked tirelessly to keep its doors open throughout the war, putting on exhibitions and concerts that supported the war effort including, Artists for Victory, Winning the Peace, and Saints for Soldiers. Such initiatives greatly contributed to the Museum’s attendance records in the midst of the war.

It is fitting to recognize these wartime accomplishments during The Met’s 150th anniversary year since 2020 has brought its own significant challenges to the Museum’s staff and collection. Our five-month closure in the face of the global pandemic has ushered in an especially difficult moment for the Museum. Despite this, Met staff have once again risen to the challenge, safeguarding the collection by conducting regular gallery patrols while others in security, engineering, and operations maintained the Museum’s complex maze of buildings. The story of The Met’s evacuation of its most irreplaceable collections to safety during World War II and the challenges the Museum faced in its 150th year underscores the dedication of Met staff, then and now.

Author's Note: I wish to acknowledge former Met colleague, Rebecca C. Grunberger (Rebecca Ben-Atar), whose graduate work on Francis Henry Taylor and World War II was an important resource for this research. See Rebecca C. Grunberger, “Our doors shall remain open”: Francis Henry Taylor and the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Great Art Evacuation during World War II, M. A. Hunter College Dept. of Art, 2011.

Editor's Note: This article was updated on January 22, 2021, to correct mention of the date the United States entered World War II.

Further reading:

Bosman, Suzanne. The National Gallery in Wartime. London: National Gallery Company; Yale University Press, 2008.

Chanel, Gerri. Saving Mona Lisa: The Battle to Protect the Louvre and Its Treasures During World War II. New York: Heliopa Press, 2014.

Mallon, MacKenzie. “A Refuge from War: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art and the Evacuation of art to the Midwest during World War II,” Getty Research Journal No. 8 (2016): pp. 147–160.