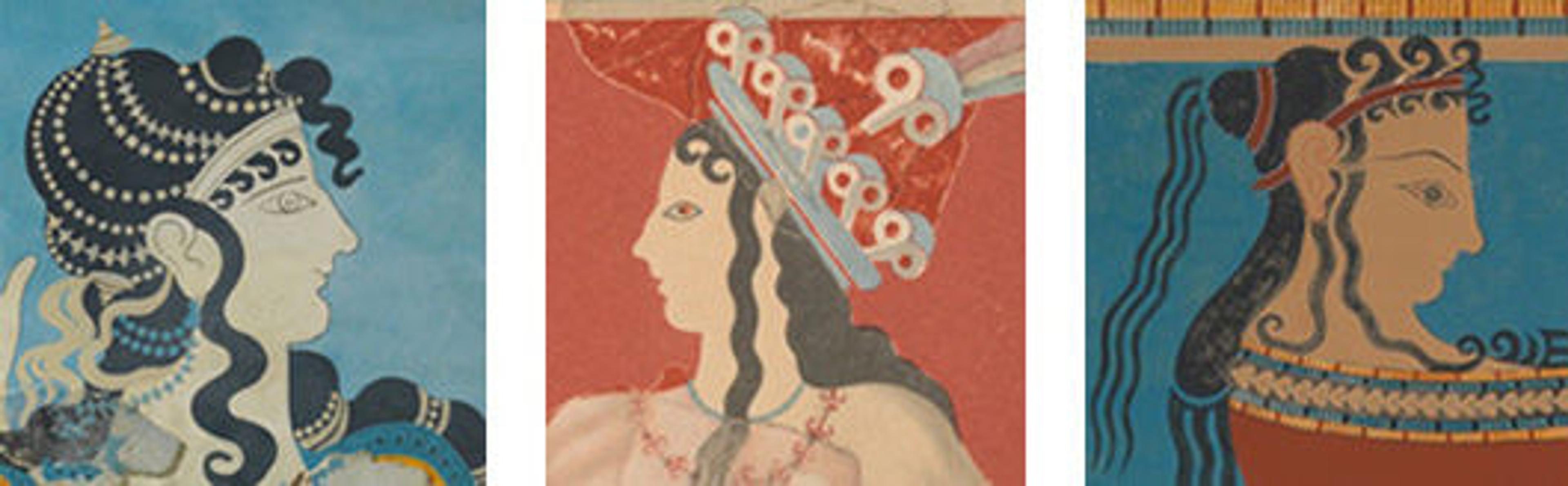

From left to right: Emile Gilliéron fils (Swiss, b. Greece, 1885–1939), Reproduction of the "Ladies in Blue" fresco from Knossos (detail), 1927. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Dodge Fund, 1927 (27.251); Sir Arthur Evans (British, 1851–1941) Frontispiece to The Palace of Minos at Knossos, vol. 2 part 2, showing the painted stucco relief of the "Priest-King" restored (detail). The Onassis Library for Hellenic and Roman Art, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York; Emile Gilliéron père (Swiss, 1850–1924), Reproduction of a fresco with a woman carrying an ivory pyxis from Tiryns (detail), 1912. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Dodge Fund, 1912 (12.128.4). Images © The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

In the second half of the nineteenth century, archaeologists began to focus on understanding prehistoric Greece and its extraordinary flowering during the Greek Bronze Age (about 3000–1050 B.C.). Heinrich Schliemann's discovery of wealthy tombs at Mycenae in 1876 brought to life the Heroic Age immortalized in the epic poetry of Homer, in which King Agamemnon’s palace was described as "rich in gold."

Twenty-four years after Schliemann's find, the British archaeologist Sir Arthur Evans began excavations at Knossos, on the island of Crete, that would yield a vast complex of buildings belonging to a sophisticated prehistoric culture, which he dubbed Minoan after the legendary King Minos. Evans hired a Swiss artist, Emile Gilliéron (1850–1924) and later his son, Emile (1885–1939), as chief fresco restorers at Knossos, where they worked for more than thirty years. The Gilliérons also established a thriving business catering to the popular demand for reproductions of antiquities from the newly identified Minoan and Mycenaean civilizations. The current exhibition Historic Images of the Greek Bronze Age: The Reproductions of E. Gilliéron & Son focuses on the colorful and carefully crafted reproductions made by the Gilliérons, which were disseminated around the world and provided a vivid impression of the new finds that inspired a generation of writers, intellectuals and artists, from James Joyce and Sigmund Freud to Pablo Picasso[1]. While there have been previous exhibitions in Europe devoted to the Gilliérons' work, this is the first such presentation in North America[2].

The Artists

Emile Gilliéron (1850–1924) was born in Villeneuve, Switzerland, where he studied art as a young man. After further training in Munich and Paris, he moved to Greece in 1876 and worked as an archaeological illustrator for Heinrich Schliemann and other researchers. At the same time, he became a noted art teacher and served as the drawing master to the princes and princesses of Greece’s royal family[3]. His most distinguished pupil was the young Giorgio de Chirico, whose later paintings, such as Ariadne, drew on the mythology of Knossos, where Gilliéron would make his greatest contributions to the study of Aegean art.

Giorgio de Chirico (Italian, b. Greece, 1888–1978), Ariadne, 1913. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Bequest of Florene M. Schoenborn, 1995 (1996.403.10). ©Foundation Giorgio de Chirico/Licensed by VAGA, New York, NY

Emile Gilliéron, fils (1885–1939), was born in Athens and shared his father’s artistic talents. After training at the Polytechnic in Athens and at the École Nationale Supérieure des Beaux-Arts in Paris, he assisted his father at Knossos. When the first campaigns of excavations of Knossos ended in 1913, he focused on the careful work of restoring the frescoes in the Herakleion Museum, re-creating spaces at the site itself and creating illustrations to be included in Evans's monumental, four-volume book, The Palace of Minos at Knossos, published between 1921 and 1936. The Greek Government named him "Artist of all the Museums in Greece," a position that he held for twenty-five years and which gave him unparalleled access to new archaeological finds.

The Minoan Frescoes at Knossos

Emile Gilliéron père (Swiss, 1850–1924), Reproduction of the "Cupbearer" fresco from Knossos, 1908. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Dodge Fund, 1909 (09.135.1). Image © The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

When numerous tantalizingly fragmentary wall paintings began to emerge at the outset of the excavations at Knossos, Evans turned to Emile Gilliéron père, who was widely recognized as the best archaeological illustrator working in Greece at the time[4]. The frescoes at Knossos were especially exciting because, more than any other find, they provided poignant glimpses into the world of the Minoans[5]. The first well-preserved image of the face of a Minoan to be discovered on one of the palace walls was that of the "Cupbearer," which Gilliéron ably restored.

Reconstruction of the "Cupbearer" fresco at Knossos. Photograph by Bruce Schwarz

The figure was part of a large procession that decorated one of the main entrances into the palace. Later, as part of Evans's effort to make ancient Knossos understandable to visitors, the younger Gilliéron would re-create more of the procession on a concrete superstructure reconstituted under Evans's guidance.

The exhibition at the Met focuses largely on the restoration of the frescoes at Knossos by the Gilliérons. The father’s body of work is particularly well represented, and includes one of the most important works on display—an early restoration of the "Priest-King," a figure that Evans believed represented one of the rulers of ancient Knossos.

Emile Gilliéron père (Swiss, 1850–1924), Reproduction of the "Priest-King" from Knossos, ca. 1906–1907. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Rogers Fund, 1907 (07.99.9a-f). Image © The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York; Sir Arthur Evans (British, 1851–1941) Frontispiece to The Palace of Minos at Knossos, vol. 2 part 2, showing the painted stucco relief of the "Priest-King" restored. The Onassis Library for Hellenic and Roman Art, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Images © The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

The "Priest-King" remains one of the most emblematic images of Minoan Crete. In 1907, the Met acquired copies of the six main fragments from the relief, which was excavated in 1901 in an area of Knossos known as the North-South Corridor. The Metropolitan’s art historians pieced the copied fragments together into a single relief based on a photograph by Gilliéron père of his first 1905 restoration, which was displayed in the newly established Herakleion Museum. The Met reconstruction differs slightly from Gilliéron's in that it provides only minimal detail of the unpreserved parts. Additional fragments of the relief were subsequently found and several more restorations were made by Gilliéron, père and fils[6]. A copy of the final version of the restoration was installed where Evans believed the original would have been located in the palace at Knossos, and an illustration of it was used as the frontispiece of the second volume of Evans’s publication about the excavations.

The restored "Priest-King" relief in situ at Knossos. Photograph by Bruce Schwarz

Scholars have long debated the validity of the Gilliéron restorations, and in the case of the "Priest-King" others have utilized the same fragments to reconstruct as many as three different figures, including one in which a sphinx wears the plumed crown. Because the remains are fragmentary, the original composition cannot be determined with certainty, but the Gilliéron restoration of the "Priest-King" in the Met’s collection remains a clever solution that combines the existing pieces into a single figure.

All of the reproductions on view in the current exhibition are at a scale of one to one, and in most cases the original fragments are carefully delineated from the restored areas. The watercolors were typically painted while the artist was in front of the originals, often at the same time as or shortly after the restorations themselves were made. Much of the restorative work has withstood subsequent research, though details of some reconstructions have been proved to be questionable or incorrect.

Attributed to Emile Gilliéron fils (Swiss, b. Greece, 1885–1939), Reproduction of the "Saffron Gatherer" fresco from Knossos, 1914. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Dodge Fund, 1915 (15.122.3). Image © The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

The "Saffron-Gather," to take a famous example, has been proved to be incorrect, as it surely represents a monkey rather than a boy. Part of the tail, unrecognized at the time of restoration but faithfully reproduced, is visible in the fragment at the far right.

Emile Gilliéron père (Swiss, 1850–1924), Reproduction of the "Bull Leapers" fresco from Knossos, ca. 1906–1907. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Rogers Fund, 1907 (07.99.17). Image © The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

The main composition of the well-known "Bull Leapers" fresco appears correct, but details of the border's restoration have been questioned. It is clear from the original fragments that the top and bottom borders consist of overlapping variegated rock patterns between narrow bands with dentil patterns; however, there is no evidence to support the rock pattern that frames the sides, and it may be a modern addition.

Emile Gilliéron fils (Swiss, b. Greece, 1885–1939), Reproduction of the "Ladies in Blue" fresco from Knossos (detail), 1927. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Dodge Fund, 1927 (27.251). Image © The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Certainly among the most famous restorations from Knossos is the "Ladies in Blue" fresco[7]. The very fragmentary painting was originally restored by Gilliéron père on the basis of other fresco fragments from Knossos, mostly of a much smaller scale. It has been shown that the artist used details of the "Cupbearer" fresco as a model for the ladies' faces, which are not preserved at all[8]. The first restoration by Gilliéron père was damaged in the Herakleion Museum during a 1926 earthquake, and Gilliéron fils was hired to restore it again in 1927; he made the Metropolitan Museum’s copy the same year. Extensive restorations like the "Ladies in Blue" fresco led the writer Evelyn Waugh, after a visit to the museum in Herakleion in 1929, to state that it was not easy to judge the merits of Minoan painting, which he thought had been influenced by contemporary fashion and the covers of Vogue magazine[9].

Above: The Queen's Megaron in the Domestic Quarter at Knossos; Below: The Throne Room at Knossos, which was restored in 1930. Photographs by Bruce Schwarz

By 1930, guided by Evans, the Gilliérons had reconstructed entire rooms in the palace at Knossos, which remains the largest Bronze Age settlement ever found on Crete[10]. Particularly good examples of Evans's grand restorations are the Queen's Megaron in the Domestic Quarter and the Throne Room.

From left to right: Emile Gilliéron père (Swiss, 1850–1924), Reproduction of a fresco with a griffin from the throne room at Knossos, 1910. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Dodge Fund, 1911 (11.37.4); Painted plaster reproduction of the "Throne of Minos," ca. 1906. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Rogers Fund, 1906 (07.51). Images © The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

The exhibition at the Met displays a watercolor of one of the majestic griffins from the Throne Room next to a plaster copy of the "Throne of Minos" that the Met purchased in 1906 directly from Sir Arthur Evans, who was curator of the Ashmolean Museum at the time. The plaster cast is painted black in places to reproduce the scorch marks on the original, which were the results of the final conflagration that destroyed the palace at the end of the fourteenth century B.C.

Evans's Pinacoteca, or Picture Gallery, at Knossos. Photograph by Bruce Schwarz

At Knossos, Evans installed a picture gallery above the Throne Room in order to hang Gilliéron copies of significant frescoes that had been removed to the Herakleion Museum. His extensive reconstructions at Knossos, which used reinforced concrete, have not been without controversy. It has even been said that the site today preserves some of the best examples of Art Deco architecture in Greece[11].

Other Minoan, Cycladic, and Mycenaean Frescoes

Emile Gilliéron père (Swiss, 1850–1924), Reproduction of the "Cat and Pheasant" and "Leaping Deer" frescoes from Agia Triadha, summer 1910. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Dodge Fund, 1911 (11.37.1a, b). Image © The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

In addition to the examples from Knossos, the exhibition includes a selection of fresco reproductions from other Bronze Age sites, including the Minoan villa at Agia Triadha on Crete, the Cycladic settlement of Phylakopi on the island of Melos, and the citadels of Mycenae and Tiryns in mainland Greece. The original frescoes from the villa at Agia Triadha were badly damaged when the building was destroyed by fire in the mid-fifteenth century B.C., darkening their appearance in some instances to the point of illegibility. Today, Gilliéron’s reproductions, made soon after the initial discovery, are in many cases more readable than the originals. The "Cat and Pheasant" fresco, in which a wild cat stalks a pheasant-like bird, is perhaps the most poignant and sensitively rendered animal scene preserved from Bronze Age Crete.

Emile Gilliéron père (Swiss, 1850–1924), Reproduction of a fresco fragment of a frieze with nautilus from Mycenae, 1915. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Dodge Fund, 1915 (15.122.6). Image © The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

A small fresco fragment from Mycenae is a particularly good example of the kind of careful archaeological illustrations that both Gilliérons did over the course of their long careers[12]. The fresco fragment, with two perpendicular painted surfaces, is illustrated in section as well. The nautilus frieze, also known from Pylos, is a particularly Mycenaean phenomenon, which draws on a marine motif that was very popular in Minoan art. Although the fragment was catalogued in 1923, this color illustration has never before been published[13].

Emile Gilliéron père (Swiss, 1850–1924), Reproduction of the "Shield frieze" fresco, 1911 or early 1912. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Dodge Fund, 1912 (12.58.1). Image © The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Gilliéron père was hired in 1910–12 by the Germans excavating at Tiryns to assist with the reconstruction of the many fresco fragments found at the site. His restoration of the "Shield frieze" fresco was made from more than two hundred fragments excavated in the Inner Forecourt of the palace at Tiryns. The distinctive figure-eight motif recalls the "Figure of Eight Shields" mentioned in Homer's epics as used by the ancient Greek warriors at Troy, thus providing an important visual link between Homer’s Age of Heroes and Late Bronze Age Greece.

Emile Gilliéron père (Swiss, 1850–1924), Reproduction of a fresco with a woman carrying an ivory pyxis from Tiryns, 1912. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Dodge Fund, 1912 (12.128.4). Image © The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Unlike the other watercolors in the exhibition, the fresco with a woman carrying an ivory pyxis, or box, from Tiryns shows no distinction between restored areas and the fragments that are actually preserved. The woman is presented as complete, but in fact much of the original painting is missing. Gilliéron's reconstruction is based on fragments from a number of figures that were part of the same procession scene[14].

Emile Gilliéron père (Swiss, 1850–1924), Reproduction of the painted limestone sarcophagus from Agia Triadha, 1909-1910. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Dodge Fund, 1910 (10.38.1). Image © The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Two reproductions of important stone works with painted plaster decoration are featured in the exhibition. The first is the "Agia Triadha Sarcophagus," which, with its complex painted scenes of funerary rituals, was among the most expensive reproductions ever made by the Gilliérons. Sir Arthur Evans complained about the cost, to which the artist, Gilliéron fils, responded that it had been a very time-consuming project[15]. The Met's reproduction was made by the elder Gilliéron and shows how father and son shared in the work of their reproduction business.

From left to right: E. Gilliéron & Son, Reproduction of a painted grave stele with warriors from Mycenae, ca. 1918–19. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Johnston Fund, 1920 (20.193.2); Detail of side of stele with incurving altars; Back view of stele reproduction. Images © The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

The second example of an important reproduction of stone work is a grave stele found in 1893 at Mycenae. The painted scenes were applied to a reused sandstone sculptured stele, of a type similar to that used for the Shaft Graves of the Grave Circles at Mycenae. The front and sides faithfully represent the original work, with its older limestone carving and painted figural scenes with warriors, animals, and altars with incurving sides, while the back reveals the plaster and wooden frame on which the reproduction was made.

Master Craftsmen and Master Forgers

From left to right: E. Gilliéron & Son, Gilt copper-alloy electrotype reproduction of a fake Minoan gold snake goddess statuette, ca. 1920. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Rogers Fund, 1921 (21.189); E. Gilliéron & Son, Reproduction of a bronze votive statuette from Tylissos, ca. 1920. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Rogers Fund, 1921 (21.192). Images © The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

It is clear that Gilliéron père and fils were inventive, talented artists capable of producing both accurate copies and clever restorations. All of the works acquired by the Met from the Gilliérons were reproductions of ancient works and sold as such. An exception is a small gold statuette of a snake goddess without provenance in the Herakleion Museum, reproduced as an electrotype in 1920, which was later recognized as a forgery. Upon close inspection, one would not confuse the Gilliéron reproductions with antiquities. The Gilliérons often stamped their work with the name of the firm as well. It is notable, however, that some pieces, such as the bronze statuettes, were made using the same techniques and materials as the ancient works they replicate, which begins to blur the line between original and reproduction, especially since these works are not stamped. Furthermore, the archives of the Metropolitan Museum show that the younger Gilliéron became quite interested in replicating ancient techniques. The Metropolitan Museum hired Gilliéron fils to go to the Cairo Archaeological Museum to make replicas of ancient Egyptian jewelry in the winter of 1922–1923. On January 11, 1925, Gilliéron, who was still working on ancient Egyptian reproductions for the Met, wrote that electrotypes would not capture certain details, and boasted that his own craftsmanship could adhere to the same specifications as an artifact of the Twelfth Dynasty[16].

Emile Gilliéron père (Swiss, 1850–1924), Reproduction of the "Phaistos Disk," 1910 or 1911. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Dodge Fund, 1911 (11.37.7). Image © The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Major forgeries of Minoan and Mycenaean antiquities—notably gold and ivory statuettes and gold signet rings and relief vessels—were being made in the first half of the twentieth century, and some scholars have suggested that one or both of the Gilliérons were forgers as well as restorers. The subject is complex and a matter of ongoing research. Contested works of art that have been attributed to them include elaborate chryselephantine snake goddesses, the gold signet rings known as the Ring of Minos and the Ring of Nestor, and the well-known disk from Phaistos on Crete[17].

Gilliéron Reproductions and the Met: The History of Displaying the Art of Prehistoric Greece in Museums

Emile Gilliéron père (Swiss, 1850–1924), Gilt copper-alloy electrotype reproduction of the gold cups from Vapheio, ca. 1906. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Dodge Fund, 1906 (06.202, .203). Image © The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

As early as 1894, the elder Gilliéron, already established as an eminent artist and archaeological draftsman, was making metal copies of important Mycenaean gold objects from molds taken directly from the originals[18]. Among the first reproductions that he sold were the spectacular gold Vapheio cups, which were excavated from a tholos tomb (a beehive-shaped structure) outside of Sparta in 1889. Gilliéron also made careful drawings of the scenes on the cups, which illustrate the capture of wild bulls.

E. Gilliéron père's drawings of the Vapheio Cups. After A. Evans, The Palace of Minos at Knossos, vol. 3 (London 1930), fig. 123

He first sold his copies through the family business on Skoufa Street in Athens, and by 1906 he had a catalogue of ninety electrotypes, manufactured in Germany by the Württemburg Electroplate Company. By 1911 the firm was known as E. Gilliéron & Son and their catalogue of "Mycenaean Antiquities"—translated into English, French, and German—had grown to 144 pieces. In addition, the Gilliérons distributed elaborate handmade catalogues of their watercolors and created other reproductions on commission.

From left to right: A Brief Account of E. Gilliéron's Beautiful Copies of Mycenaean Antiquities in Galvano-Plastic. Sale Catalogue (Württemberg: Würtembergische Metallwarenfabrik, ca. 1906); Emile Gilliéron père (Swiss, 1850–1924), Handwritten and illustrated catalogue page: "Phot. IX. Partie nod de la procession," ca. 1910. The Archives of the Onassis Library for Hellenic and Roman Art, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Images © The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

For several decades, major museums and institutions in Europe, such as the South Kensington Museum in London (now the Victoria and Albert Museum) and the Winckelmann Institute in Berlin, acquired Gilliéron reproductions to be displayed and studied. Even the National Museum in Athens had a gallery devoted to Gilliéron replicas of Greek Bronze Age art.

Between 1906 and 1932 the Metropolitan Museum acquired hundreds of reproductions of prehistoric Greek art from the firm of E. Gilliéron & Son and displayed them alongside original antiquities, with the intention of presenting as complete a record as possible of this remarkable period in art history[19].

The Gallery for Prehistoric Greek Art at the Metropolitan Museum, 1933. Image © The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

It is notable that in many cases the Museum commissioned the copies, with the excavators’ permission, shortly after the originals were discovered and before they were fully published. The frescoes excavated in 1903 at Agia Triadha, for example, were not fully published until 1998 and, excluding a visit to the Herakleion Museum on Crete, the Gilliéron watercolor reproductions offered the best opportunity for nearly a century to view images of these works[20]. The Gilliérons’ one-to-one scale replicas, typically executed in painted plaster or as metal electrotypes, documented the extraordinary, colorful objects in a way that photography was unable to do at the time. They formed part of the Metropolitan's much larger collection of plaster casts and electrotypes of world art, while the watercolor reproductions of paintings reflected antiquarian practices prevalent at the time—evident in the Museum itself, most prominently in the galleries of Egyptian art[21].

From left to right: Emile Gilliéron père (Swiss, 1850–1924), Electrotype reproduction of the gold "Mask of Agamemnon" from Mycenae, ca. 1906. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Dodge Fund, 1906 (06.224); Emile Gilliéron père (Swiss, 1850–1924), Electrotype reproduction of a gilt-electrum one-handled cup from Mycenae, ca. 1906. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Dodge Fund, 1906 (06.206); Emile Gilliéron père (Swiss, 1850–1924), Reproduction of a dagger from Mycenae, ca. 1906. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Dodge Fund, 1906 (06.220). Images © The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

In many cases, the Gilliérons reworked molds taken from original antiquities in order to re-create an object in its original undamaged form. They offered two versions of the famed gold funerary mask from Shaft Grave V in Grave Circle A at Mycenae, which came to be known as the "Mask of Agamemnon." One represented the mask as it looked when it was found, the other (see image above) restored it to its presumed original appearance. In the case of the gilt electrum one-handled cup from Shaft Grave IV, Gilliéron père straightened the stem and smoothed the corroded surface for his reproduction in an attempt to capture the original splendor of the large ritual vessel. For the elaborately decorated Mycenaean swords and daggers found in the tombs of Mycenae, the Gilliérons sometimes worked with a variety of materials, such as the ivory and blue glass in the example above, in order to re-create an impression of the objects’ ornate details.

From left to right: Emile Gilliéron père (Swiss, 1850–1924), Painted plaster reproduction of a tall spouted breccia-stone vase from Mochlos, ca. 1909-1910. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Dodge Fund, 1910 (10.38.7); Painted plaster reproduction of a terracotta stirrup jar from Gournia, ca. 1914. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Dodge Fund, 1915 (15.26.1) Images © The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

The Gilliérons were not the only manufacturers of Minoan and Mycenaean reproductions between 1900 and 1925, but they were generally considered to be the best. Their painted plaster copies of Minoan stone vases and painted pottery are as meticulous as they are masterful.

From left to right: Painted plaster and wood reproduction of the stone "Harvesters' Vase" from Agia Triadha, ca. 1907-1908. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Gisela M. A. Richter, 1908 (08.266a–c); The Gillierons' restored version of the "Harvesters' Vase." The Archives of the Onassis Library for Hellenic and Roman Art, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Images © The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Reproductions of selected Minoan works, including the "Harvesters' Vase" from Agia Triadha, were made and sold at the Herakleion Museum. The Gilliérons produced their own version with the missing lower half completely restored.

Halvor Bagge, Painted plaster reproduction of a Minoan Marine-style terracotta vase from Egypt in the Borély Museum, Marseilles, 1925–26. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Dodge Fund, 1926 (26.86.9). Image © The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Halvor Bagge, a Scandinavian artist who worked with Arthur Evans, also made a number of reproductions of Minoan and Mycenaean antiquities that he offered for sale[22]. The Metropolitan has a number Bagge's replicas, including the faience snake goddess from the Temple Repositories at Knossos and a Minoan marine style vase found in Egypt in 1893 from the collection of the Borély Museum in Marseilles (shown above).

One of the more interesting special commissions that the Met purchased from the Gilliérons is a copy of the ivory leaper from Knossos. Made of plaster with a metal armature to stabilize the core, it reproduces the ravaged surface of the ivory. In 1920, the Gilliérons made a restored version of this statuette in painted plaster with long black hair and a belted codpiece and offered it for sale to the Museum.

Clockwise from top left: E. Gilliéron & Son, Painted plaster reproduction of an ivory leaper from Knossos, ca. 1918–19. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Rogers Fund, 1920 (20.100.1); The Gilliérons' restored version of the ivory leaper from Knossos. The Archives of the Onassis Library for Hellenic and Roman Art, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York; X-radiograph of the ivory leaper reproduction. On file in the Sherman Fairchild Center for Objects Conservation, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Images © The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Gisela Richter, who joined the Museum staff in 1906 and was curator in charge of Greek and Roman Art from 1925 to 1948, tended to shy away from such extensively reconstructed reproductions, but heavily restored casts were used at other institutions for educational purposes and displays in which they were sometimes paired with unrestored or less restored plaster copies[23].

E. Gilliéron & Son, Painted plaster reproduction of a gaming board from Knossos, 1916-1920. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Rogers Fund, 1917 (17.231). Image © The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Another extraordinary object from Knossos was the "Royal Gaming Board." The original object, excavated north of the Loom-weight Basement, was an exceptionally elaborate construction made with inlays of ivory, rock crystal, and glass paste, decorated with kyanos blue and gold and silver sheet metal, on a wooden base. Four ivory gaming pieces were found nearby. The details of how the game was played are not known, but it may have had a ritual context[24]. Inlaid gaming boards were also used by neighboring cultures during the Bronze Age, especially in the ancient Near East. The Met specially commissioned a reproduction of the Knossos "Royal Gaming Board" in 1916 and the Gilliérons spent several years working on it in an effort to make their copy as accurate as possible.

Emile Gilliéron fils (Swiss, b. Greece, 1885–1939), Gilt silver reproduction of a gold bee pendant from Mallia, 1931. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Fletcher Fund, 1932 (32.26). Image © The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Gilliéron fils continued to make and sell reproductions until his death in 1939, but the Metropolitan moved steadily away from acquiring replicas until the practice was abandoned entirely in favor of original works of art. The last reproduction of prehistoric Greek art purchased by the Metropolitan from Gilliéron fils was the gold bee pendant from Mallia, made less than two years after the original was discovered in 1930. Gilliéron fils fashioned the copy "by hand with great finesse" in imitation of ancient techniques[25].

Eventually all of the Gilliéron reproductions that had been purchased by the Museum were removed from display and packed away for safekeeping; the reproductions on display in the current exhibition are on view for the first time in decades[26]. Thanks to their historical importance and usefulness as study references, as well as the precision with which they were made, these works remain valuable representations of ancient artistic achievements that continue to inspire wonder and delight.

Related Links

Exhibition: Historic Images of the Greek Bronze Age: The Reproductions of E. Gilliéron & Son

Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History: "Minoan Crete"; "Mycenaean Civilization"; "Early Cycladic Art and Culture"; "Prehistoric Cypriot Art and Culture"

Citation

Hemingway, Seán. "Historic Images of the Greek Bronze Age". New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000–. http://www.metmuseum.org/now-at-the-met/features/2011/05/17/historic-images-of-the-greek-bronze-age.aspx

Acknowledgments

I am most grateful to Thomas P. Campbell, Director of the Metropolitan Museum, and Carlos A. Picón, Curator in Charge of the Department of Greek and Roman Art, as well as my colleague, Joan R. Mertens, and other members of the Department of Greek and Roman Art who worked with me on the exhibition: Michael J. Baran, Fred A. Caruso, William M. Gagen, Debbie T. Kuo, John F. Morariu, Jr., Matthew A. Noiseux, Jennifer Slocum Soupios, and the interns Allia Benner, Amie Blackman, Jacob Coley, and Alexandra Pearsall. My thanks go to Mark C. Santangelo, Librarian of the Onassis Library, for bibliographic assistance and assistance with the Gilliéron archives in the Department of Greek and Roman Art, and to James Moske for assistance with the Museum's archives. Many thanks to Eileen M. Willis for editing this article, and to Barbara Bridgers of the Photo Studio and her photographers Joseph Coscia, Jr., and Bruce Schwarz, who took the excellent images of the pieces in the exhibition, many of which are illustrated in this article, and to Lucy Redoglia, who prepared the images for online publication. I am also grateful to the American School of Classical Studies in Athens and the Greek Archaeological Service for facilitating my request to photograph the Gilliéron restorations at Knossos and to Bruce Schwarz for accomplishing this with me in the summer of 2009. I would like to acknowledge the fruitful collaboration of Marjorie Shelley and her colleagues in the Department of Paper Conservation, who worked diligently on the conservation of the Gilliéron watercolors, as well as Dorothy H. Abramitis in the Department of Objects Conservation, who conserved the other works in the exhibition. The Brady Foundation provided essential funds for the conservation of the Gilliéron watercolors. Numerous other colleagues assisted with the exhibition and I would like to single out the following: Nina McN. Diefenbach, Patricia A. Gilkison, Michael Lapthorn, Mortimer Lebigre, Carol Lekarew, Taylor Miller, Marcie Muscat, Jennifer Russell, Linda Sylling, and Egle Zygas. For scholarly consultations, I thank Amy Brauer, Sophie Descamps, Susanne Ebbinghaus, Robert B. Koehl, Kenneth Lapatin, Colin Macdonald, J. Alexander MacGillivray, Nanno Marinatos, Nicoletta Momigliano, L. Hugh Sackett, Malcolm H. Wiener, and especially Colette C. Hemingway. Finally, none of this would have been possible without the generous exhibition support from The Vlachos Family Fund. I am particularly thankful to Peter Vlachos for his enthusiastic support.

Notes

[1] Two recent books have looked at the impact of the discoveries at Knossos and Cretan myths on modern art, literature, and philosophy. See C. Gere, Knossos & the Prophets of Modernism (University of Chicago Press, Chicago 2009); T. Ziolkowski, Minos and the Moderns. Cretan Myth in Twentieth-Century Literature and Art (Oxford 2008). One of the earliest artists known to have visited the excavations at Knossos was the Russian painter Léon Bakst. See L. Davydova, "Knossos Palace on Crete in the Drawings of Léon Bakst," Transactions of the State Hermitage XLI. The World of Classical Antiquity Art and Archaeology (Saint Petersburg 2008), pp. 263–303, in Russian with English summary on pp. 359–360.

[2] See V. Stürmer, Gilliérons Minoisch-Mykenische Welt. Ein Ausstellung des Winckelmann-Instituts Katalog (Berlin 1994); C. Haywood, All that glitters … An exhibition of replicas of Aegean Bronze Age plate. The Classical Museum April–June 2000 (University College Dublin 2000). In the summer of 2010 there was an exhibition entitled "El mundo minoico-micénico y la obrade emile gilliéron e hijo" at the Museo Nacional de Bellas Artes in Havana, Cuba.

[3] For more detailed biographies of Emile Gilliéron père and fils, see R. Hood, Faces of Archaeology in Greece. Caricatures by Piet de Jong (Leopard’s Head Press, Oxford 1998), pp. 22–26; K. Lapatin, Mysteries of the Snake Goddess. Art, Desire, and the Forging of History (Houghton Mifflin Company, Boston 2002), especially pp. 120–139; V. Stürmer, "Gilliéron als Vermittler der ägäischen Bronzezeit um 1900," Studia Hercynia 8 (Prague 2004), pp. 37–44, pls. VIII–XII, especially pp. 39-41.

[4] On Sir Arthur Evans and the Gilliérons at Knossos, see J.A. MacGillivray, Minotaur. Sir Arthur Evans and the Archaeology of the Minoan Myth (Farrar, Straus & Giroux, New York 2000); J. Evans, Time and Chance. The Story of Arthur Evans and his Forebears (Longmans, Green and Co., London 1943), esp. pp. 330, 377; A. Brown, Arthur Evans and the Palace of Minos (Ashmolean Museum, Oxford 2000).

[5] On the significance of fresco paintings, see A. Chapin, "Frescoes," in E. H. Cline, ed., The Oxford Handbook of the Bronze Age Aegean (Oxford 2010), pp. 223-236.

[6] For a discussion of the "Priest-King" with previous bibliography, see S. Sherratt, Arthur Evans, Knossos and the Priest-King (Ashmolean Museum, Oxford 2000); M. Shaw, "The 'Priest-King' Fresco from Knossos: Man, Woman, Priest, King, Someone Else?" in A. P. Chapin, ed., Charis: Essays in Honor of Sara A. Immerwahr Hesperia Supplement 33 (American School of Classical Studies at Athens, Princeton 2004), pp. 65–84; N. Marinatos, Minoan Kingship and the Solar Goddess: A Near Eastern Koine (University of Illinois Press, Urbana, Chicago and Springfield 2010), especially pp. 14–18. Another slightly different version of the "Priest-King" by the Gilliérons is published in C. Praschniker, Kretische Kunst (Leipzig 1921), pl. 13. For how the restoration of the original "Priest-King" looks today, see Archaeological Museum of Herakleion. Temporary Exhibition (Athens 2007), p. 70.

[7] A detail of one lady's head—entirely the work of Gilliéron—graces the spine of the most recent edition of the Blue Guide to Crete. See P. Pugsley, Blue Guide Crete (8th edition, London 2010).

[8] See M. A. S. Cameron, "The Lady in Red: A Complementary Figure to the Ladies in Blue," Archaeology Magazine 24.1 (1971), pp. 35–43.

[9] E. Waugh, Labels. A Mediterranean Journal (Penguin Books 1985, reprint of Gerald Duckworth and Company Ltd 1930 edition), p. 112.

[10] On Knossos, see E. H. Cline, ed., The Oxford Handbook of the Bronze Age Aegean (Oxford 2010), pp. 529–542; C. F. MacDonald, Knossos (The Folio Society, London 2005); J. W. Myers, E. E. Myers, and G. Cadogan, The Aerial Atlas of Ancient Crete (University of California Press, Berkeley 1992), pp. 124–147.

[11] J. K. Papadopoulos, "Knossos," in M. de la Torre, ed., The Conservation of Archaeological Sites in the Mediterranean Region (The Getty Conservation Institute, Los Angeles 1997), pp. 93–125, esp. pp. 115–116; J. K. Papadopoulos, The Art of Antiquity. Piet de Jong and the Athenian Agora (American School of Classical Studies at Athens 2007), p. 13.

[12] One of the archaeological publications illustrated with watercolors by E. Gilliéron, fils, is C. W. Blegen, Korakou. A Prehistoric Settlement near Corinth (American School of Classical Studies at Athens, Boston and New York 1921), pls. 1–7.

[13] See W. Lamb, "Excavations at Mycenae," Annual of the British School at Athens 25 (1921–1923), pp. 171–172, no. 18. I am grateful to Dr. Lena Papazoglou and Professor Nanno Marinatos for assistance with this reference.

[14] S. A. Immerwahr, Aegean Painting in the Bronze Age (The Pennsylvania State University Press, University Park and London 1990), pp. 114–117, 202 catalogue Ti No. 4.

[15] See letter from E. Gilliéron fils to Arthur Evans dated February 14, 1911, Evans Archive, Ashmolean Museum, Oxford University. I am grateful to Dr. Yannis Galanakis for assisting me with the Gilliéron correspondence in the Evans Archive.

[16] E. Gilliéron, fils, to Albert M. Lythgoe, January 11, 1925, Office of the Secretary Records, The Metropolitan Museum of Art Archives.

[17] On the snake goddesses and other questionable ivory statuettes, see K. Lapatin, op. cit. note 3; S. Hemingway, "The place of the Palaikastro Kouros in Minoan bone and ivory sculpture," in J.A. MacGillivray, J. M. Driessen, and L. H. Sackett, eds., The Palaikastro Kouros. A Minoan Chryselephantine Statuette and its Aegean Bronze Age Context (British School at Athens Studies 6, London 2000), pp. 113–122, especially pp. 119–121. See also K. Lapatin, "Forging the Minoan Past," in Y. Hamilakis and N. Momigliano, eds., Archaeology and European Modernity: Producing and Consuming the 'Minoans' Creta Antica 7 (2006), pp. 89–105. Nanno Marinatos has made compelling arguments that the Ring of Minos and the Ring of Nestor were forgeries by E. Gilliéron, fils. On the Ring of Minos, see N. Dimopoulou and Y Rethemiotakis, The Ring of Minos and Gold Minoan Rings. The epiphany cycle (Athens 2004). On the Nestor ring, see N. Marinatos with B. Jackson, "The Pseudo-Minoan Nestor Ring and Its Egyptian Iconography," Journal of Ancient Egyptian Interconnections Vol. 3:2 (2011), pp. 6–15. Available at http://jaei.library.arizona.edu. The suggestion that the Phaistos disk is a forgery by one of the Gilliérons is put forward in J. M. Eisenberg, "The Phaistos Disk: A 100-Year-Old Hoax? Addenda, Corrigenda, and Comments,” Minerva September/October (2008), pp. 15–16, esp. p. 15.

[18] In 1894, Gilliéron offered to make electrotype copies of the Vapheio cups for Salomon Reinach, then curator of the National Archaeological Museum in Paris. The museum went on to acquire a number of reproductions from E. Gilliéron & Son to augment their archaeological collection. I am grateful to Dr. Anaïs Boucher, curator at the Musée d’archéologie nationale in the Château de Saint-Germain-en-Laye, Paris for sharing copies of their Gilliéron correspondence with me.

[19] See G. M. A. Richter, "Reproductions of Mycenaean Metalwork," MMAB (1906), pp. 123–124; G. M. A. Richter, Cast Catalogue. The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Greek and Roman Art (New York 1908), pp. 25–34.

[20] See P. Militello, Hagia Triada I. Gli Affreschi (Padua 1998).

[21] The Harvard Art Museum has a collection of fifteen Gilliéron watercolor reproductions of Minoan and Mycenaean frescoes that were long displayed in the Van Rensselaer Room of the Fogg Museum and currently hang in the lecture hall of the Sackler Museum. Their paintings were acquired directly from Gilliéron fils in 1926. Harvard also has many of the Gilliéron electrotype reproductions, which professors, such as Emily Vermeule and David Gordon Mitten, used as teaching aids in their Aegean Bronze Age seminars. I am grateful to Amy Brauer for assisting me when I came to study their Gilliéron watercolors in 2009.

[22] Bagge was also a collector of Medieval and Byzantine art. See C. DeKay, Exhibition of the Halvor Bagge Collection of Byzantine Paintings, Carvings, Manuscripts, Embroideries, Etc. (The Ehrich Galleries, New York 1915).

[23] See C. Haywood, The making of the Classical Museum: Antiquarians, Collectors and Archaeologists. An exhibition of The Classical Museum, University College Dublin (Dublin 2003). The illustration on p. 14 shows a display in 1912 of replicas of prehistoric Greek art, including many made by the Gilliérons. Two painted plaster versions of the Boxer Rhyton from Agia Triadha are displayed side by side. One is gilt and the other is not. Next to these is a painted plaster copy of an inscribed Minoan stone offering table paired with a fully restored plaster version. I am grateful to Professor Haywood for showing me the Gilliéron reproductions in the Classical Museum at UCD in Dublin in October 2010. The National Museum of Ireland in Dublin also has Gilliéron replicas. On the history of the collection and its significant holdings of casts, see L. Mulvin, Roman and Byzantine Antiquities in the National Museum of Ireland—A Select Catalogue (Wordwell Limited, Bray 2006), pp. 12–18. I am grateful to Professor Mulvin for assisting me with the study of their Gilliéron electrotypes.

[24] For further reading, see N. Hillbom, Minoan Games and Game Boards (Lund 2005).

[25] E. Gilliéron, fils, to Gisela M. A. Richter, November 24, 1931, The Onassis Library for Hellenic and Roman Art, Archives.

[26] On the history of the Greek and Roman collection and its display at the Met, see C. A. Picón, "A History of the Greek and Roman Department," in C. A. Picón et al., Art of the Classical World in the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Greece, Cyprus, Etruria, Rome (New York 2007), pp. 2–23.