«A Metropolitan Museum patron interested in Islamic art in the 1880s would have found little of relevance on display.1 By 1910, however, the situation was very much improved, and in the century since then, the Islamic art displays at the Museum have become the largest in the Western world. This essay briefly describes the evolution of the display of Islamic art at the Metropolitan Museum—from the first largely visual exhibitions to the present scholarly organization by style, material, and civilization.»

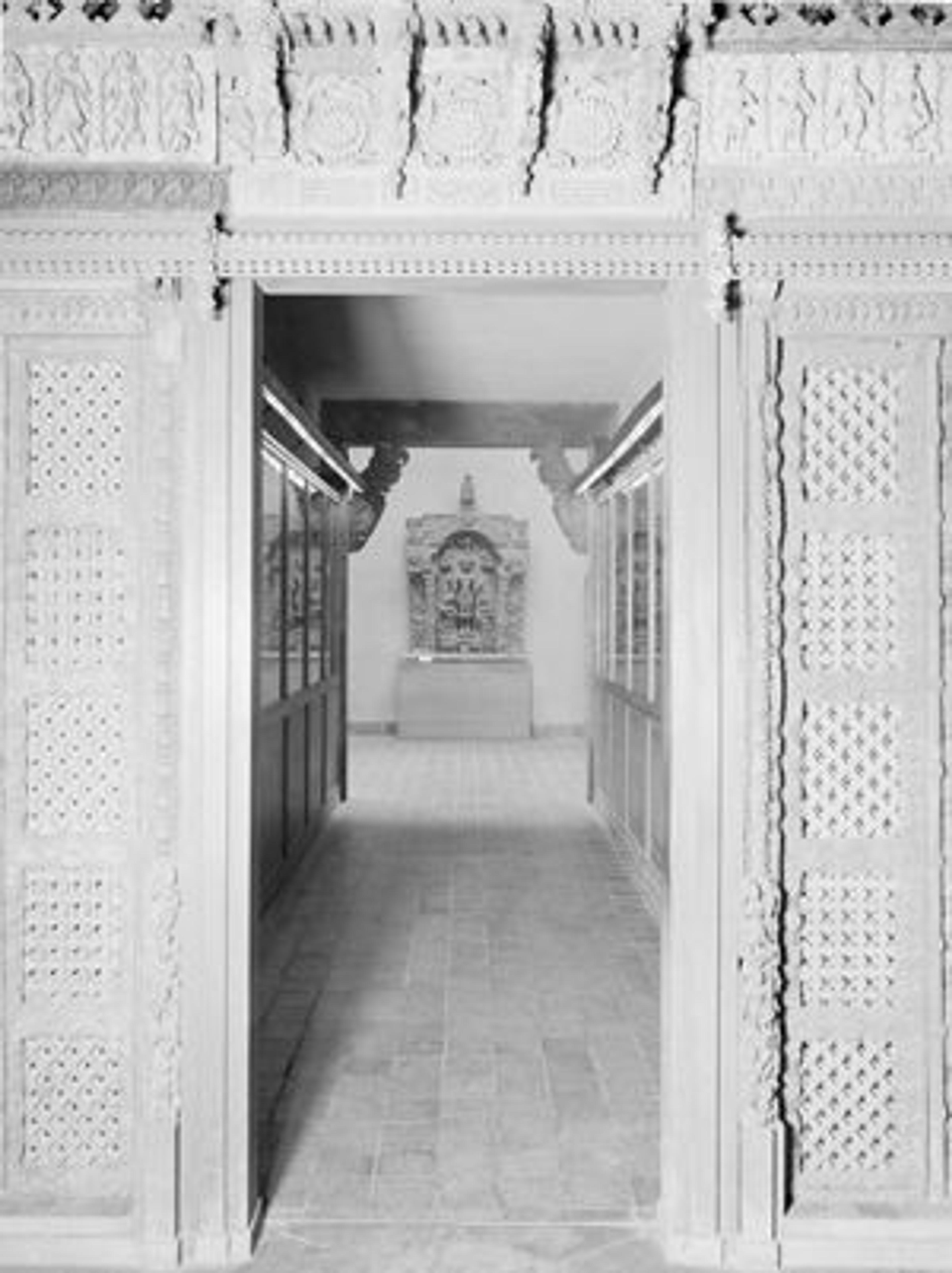

A Museum postcard showing Gallery E-14, the so-called "Persian Room," looking north into Gallery E-13, on October 2, 1912. The Museum sometimes used the terms "Persian" and "Assyrian" to distinguish Islamic-period art from ancient Near Eastern art, regardless of country.2

Many nineteenth-century viewers came to appreciate art from the Islamic world through the then-popular taste for the "exotic" exemplified in Orientalist paintings of the day (such as those displayed in Gallery 804, one of the entrances to the new galleries of Islamic art).3 At the same time, at museums including the Metropolitan, the "decorative" arts—and most Islamic art in museums is decorative—received less space and attention than the so-called fine or noble arts of painting, sculpture, and architecture. Decorative arts were often displayed by material and were thus apt to be shown together in rooms devoted to, for example, "gold," whether from the Medicis or the Mughals. During this era, when both travel and photography were difficult and expensive, curators sought to educate the viewing public by exposing them to marvels they could not otherwise encounter, but there was little emphasis on organization by time, place, or style.

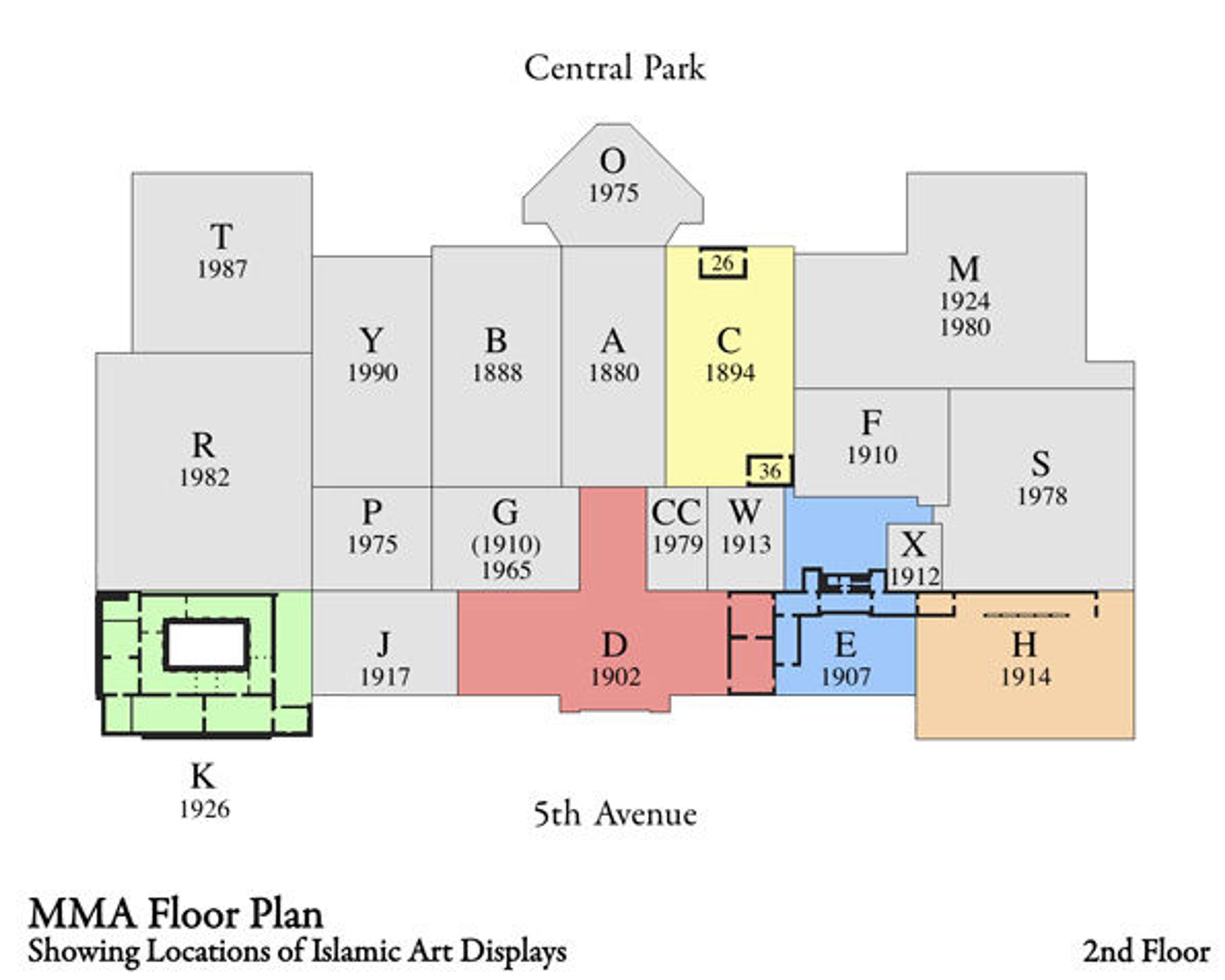

Above: Diagram of the second floor, showing locations and dates of Islamic Art displays; Below: enlarged views of highlighted wings. Diagrams by Brian Cha, Design Department

Thus, in the Museum's 1880 building (Wing A), one room displayed two porcelains from "Hindoostan" and at least four Persian hard- and soft-paste porcelains, and in another gallery, Persian tiles were interspersed with a hodgepodge of Chinese and Japanese ceramics. When Wing B was added in 1888, "figured Persian tiles" were displayed in what was then called the Hall of Ancient Statuary alongside Cypriot, Phoenician, Greek, and Egyptian fragments. Works that have now been identified as Islamic textiles were shown with Greek and Roman glass.4 Although even in the earliest years, the Museum's collections already included Islamic glass, metalwork, textiles, jewelry and ceramics, and eight "Persian" or "Turkish" carpets, these objects were not displayed as Near Eastern, let alone Islamic, art.5

Several factors precipitated gradual progress toward a purposeful organization of Islamic art at the Museum. First was the acquisition of significant individual assemblages of Islamic art, collected by people passionate about their particular areas of interest. Many of these collectors insisted that their objects be displayed together as a condition of making their gifts; the effect was that the Museum began to show Middle Eastern glass or carpets or miniatures all together. For example, the 1891 bequest of silversmith Edward C. Moore, artistic director of Tiffany & Co., for the first time meant that a visitor could see woodwork, glass, and metalwork from the central Islamic lands unified and labeled in separate galleries.6

Gallery C-26, May 9, 1907. The Moore Collection of Oriental Glass, in the Museum's earliest photo of an "Islamic" display. Later that year, Decorative Arts Curator Wilhelm Valentiner removed the dark Victorian velvet draperies in favor of walls in "grey verging on sage green" and added more contemporary cases with glass shelves. Moore's collection included Islamic textiles, seen on the wall behind the glass case, but the enameled glass shown was most significant for the Museum. Visible are Safavid and Qajar glass, a Mameluk mosque lamp, and a tazza.

Gallery C-36, November 11, 1914. In 1913 Benjamin Altman, the department store magnate, left to the Museum much of his great art collection, including the Chinese porcelain and Oriental carpets shown here. Altman's bequest filled five galleries and included sixteen Turkish, Indian, and Persian carpets, including the Herat at left, which had earlier been lent to the Museum for its seminal 1910 Oriental carpet exhibition, Safavid/Ottoman porcelains and metalwork, and numerous Chinese porcelains, seen in the center cases.7

Gallery K-33, April 13, 1926. Wing K, which opened in 1926, was specifically designed to house the Altman Collection in Galleries K-30–36. Gallery K-33 is now part of Galleries 454 and 455, "Egypt and Syria" and "Iran and Central Asia." Shown at left is Ellen Rand's portrait and memorial tablet of Mr. Altman, European furniture, a pair of silk Kashans flanking the door at rear, and an Indian carpet. This installation is a fine example of the 1920s style of display, which often included decorative arts objects of different cultures and materials displayed together. The original McKim skylight has since been blocked. The 1953 decision of the Altman trustees to allow the Collection to be dispersed for display with other related objects in the Museum cleared the way for the eventual occupation of the Altman Wing K space by the Islamic Department.

The second factor was the trend toward specialized temporary exhibitions, which were an exception to the then-widespread disregard for consistency of time, style, and place in museum displays of Near Eastern art. The Metropolitan began mounting major temporary exhibitions of Islamic art as early as 1910. Many of these exhibitions celebrated or led to permanent additions to the collection and were accompanied by complete illustrated catalogues that remained in print long after the exhibitions closed, and thereby expanded both professional and popular understanding of Islamic art. The first such exhibition consisted of forty-nine Oriental rugs from the Museum collections and those of twelve American and European individual and institutional lenders and occasioned the first Metropolitan publication on an Islamic art subject.8 Rugs lent for the exhibition subsequently came to the Museum, including a Persian animal carpet from C. F. Williams, in 1912, and other works bequeathed in 1914 by Benjamin Altman.

Gallery E-1, November 7, 1910. This first Met exhibition of art of a specifically Islamic subject, entitled Early Oriental Rugs, was curated and had an illustrated catalogue by Decorative Arts Curator Wilhelm Valentiner.

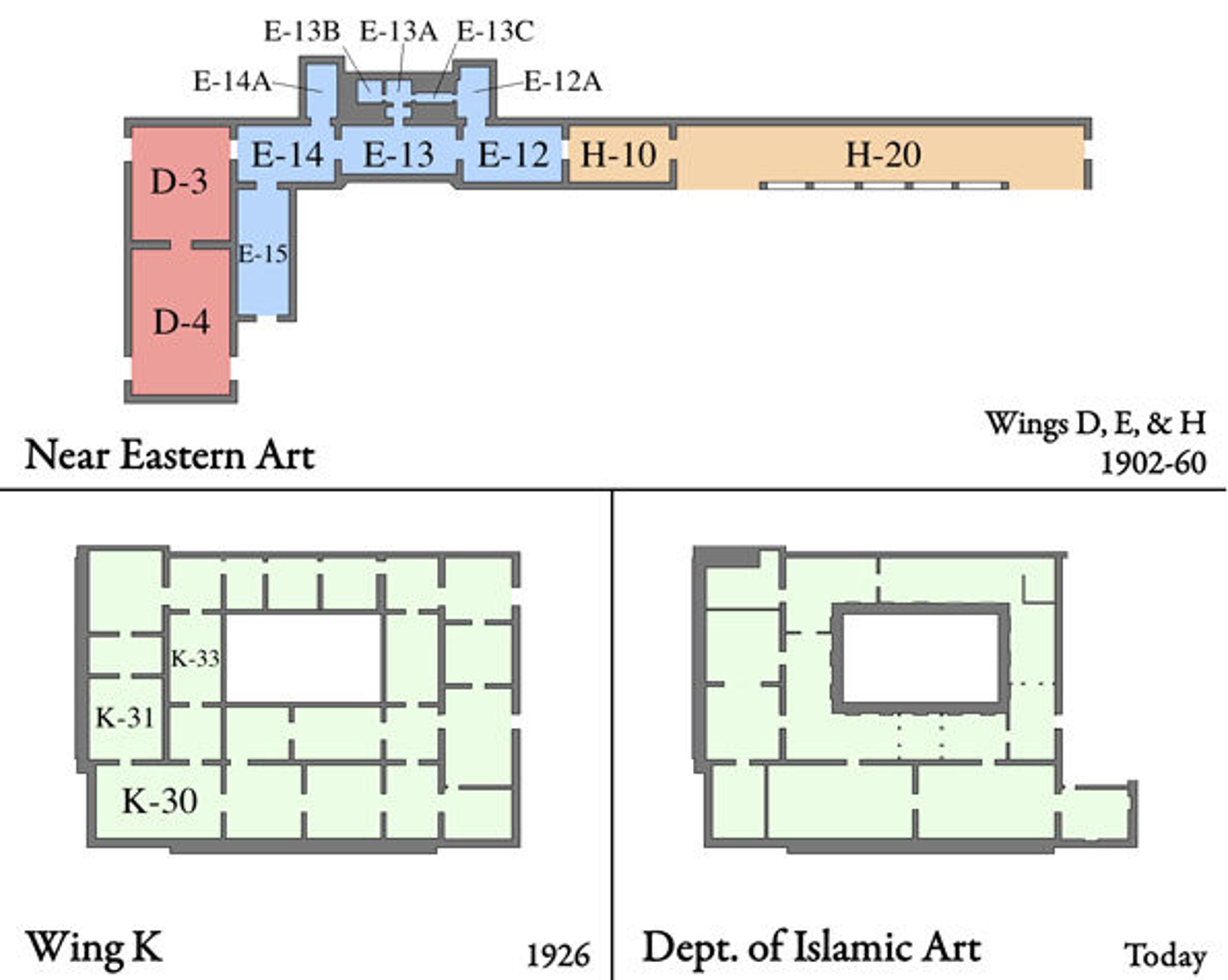

The third factor was the growth of the Museum—in personnel, including some staff members who were knowledgeable about Islamic art, and in space, which permitted the separate display of Near Eastern art. Between 1902 and 1912 the Museum built wings D, E, and H north along Fifth Avenue, where Islamic art was displayed until the 1970s.9 Wing K, where Islamic art is today, was completed between 1915 and 1926. These were the brick-and-mortar foundations for the current displays of Islamic art; the organizational evolution took far longer.

Decorative Arts Origins of the Islamic Displays

In the Museum's early years, its Islamic art collection consisted of decorative arts,10 which were deemed "crafts" or industrial art.11 However, shortly after the turn of the twentieth century, Islamic art benefitted from and arguably contributed to12 an increased respect for all decorative arts.13 One mark of this increasing respect came in 1907, when the Metropolitan established a Department of Decorative Arts, which included both Far and Near Eastern applied art. Previously, the Museum had only three curators—of paintings, sculpture, and casts—and lacked curatorial expertise in Near Eastern art. (In 1902, when the collector Osgood Field offered the pick of his Ottoman ceramic collection, the Museum had to ask the dealer Dikram Kelekian to determine whether the pieces in question were good. They were.14) The new Decorative Arts curator, Dr. Wilhelm Valentiner, filled this knowledge gap and sought to build the Near Eastern collection systematically. Examples of his acquisitions include the Ardebil animal carpet bought from the Charles T. Yerkes sale in 1910, and the Museum's first purchase, in 1912, from the dealer Hagop Kevorkian, who also donated Rhages ware he excavated personally and whose foundation continues to support the Department of Islamic art. In 1913 he solicited a donation of thirty Indian and Persian miniatures and twenty-four manuscripts from Alexander Smith Cochran.15

Gallery E-12, June 27, 1918, with Near and Far Eastern objects from the Moore Collection in new metal cases. Curators were pleased when the Museum opened a metal shop in 1912 to make sleek display cases that replaced the heavy wooden one shown in the preceding (1907) photo of the Moore Collection. An unglazed ceramic vase is visible on the floor, and Safavid and Ottoman ceramics and Spanish lusterware are in the cases on the walls. The carpets are primarily nineteenth century. E-12 was a primary display gallery for Islamic objects for approximately fifty years. The Moore Collection moved from Wing C to Wing E in 1910, and to Wing H after 1912.

The same space, Gallery E-12, in 1950. The display style was much less cluttered. Gauze shades for the skylights seen in the 1918 photo—shown furled—are still in use at this time.

Gallery E-13, June 26, 1918, looking south into Gallery E-14. Although sometimes called the "Central Persian" Gallery, it appears to have displayed mostly Indian art, including metalwork and wooden doors, and was one of three large Near Eastern art galleries between 1910 and 1975.

By the beginning of World War I, the Metropolitan had knowledgeable curators, donors passionate about sharing their interests, space to display Near Eastern art, and an established tradition of scholarly temporary exhibitions.16 A fourth and final factor advanced the display of Islamic art at the Museum: works were more available and far less expensive than traditional Old Master paintings, which also meant that people and institutions were willing to lend them. From the early 1900s through the late 1950s, a Museum visitor would have seen both an increasingly comprehensive permanent collection of Islamic-era art and, on many occasions, significant special exhibitions.

The first Plant Form in Ornament exhibition, March 21, 1919. The exhibition was conceived during the war as a patriotic means "to give art designers a new trend and inspiration . . . better than Germany and Austria" and featured many items from the Near Eastern collections. Nineteen items were from the Islamic world: tiles, ceramics from the Osgood Field collection, and several carpets and textiles, including the Ottoman tulip velvet panel at left rear. The 1919 show was displayed in one of the classroms in the Museum basement, and the aesthetic was still distinctly Victorian.

Another view of the Plant Form in Ornament exhibition, 1919. Although it was installed for only six weeks, the exhibition was immensely popular and conversations about reprising it began almost immediately. The repeat did not occur until 1933, however.

The 1933 version of the Plant Form in Ornament exhibition included an Iznik bowl decorated with carnations and tulips from the 1902 Osgood Field donation of Turkish ceramics. It was displayed with live carnations and an Italian velvet. The 1933 show reflected the streamlined Art Deco style of the 1920s and 1930s; gone was the clutter of the 1919 presentation.

The New York Aquarium kept this pool featured in the 1933 Plant Form in Ornament exhibition stocked with fish.

From the Great War until the Second World War: The Focus Narrows

By the early 1920s, seven major galleries were devoted to Islamic art. Within them, however, Islamic and non-Islamic pieces were still displayed together with little explanation of temporal, stylistic, or geographical relationships between the objects. Over the next twenty years, the expansion of the collections allowed more and more specialization and refinement in the displays.

The entrance to Gallery E-13C, April 19, 1921. This small passageway had been built in 1912 and was pressed into service as a display gallery in 1919 as the collections expanded. Here it is seen with Indian jewelry cases lining both walls, looking north into gallery E-12A, which contained Indian sculpture.

One major step occurred in 1923, when a new associate curator in the Department of Decorative Arts, Dr. Maurice Dimand, organized a separate sub-department for Near Eastern art, which included Indian art dated after 1000 B.C. and Near Eastern art dated after the death of Alexander the Great in 323 B.C. Dimand guided the growth of the Islamic collections until his retirement in 1959. He contributed significantly to the recognition of Islamic art as a separate field—not just at the Metropolitan, but worldwide—through his publication of Handbook of Mohammedan Decorative Art, a comprehensive illustrated survey based on the Metropolitan Islamic collections.17 Under his aegis the modern displays begin to emerge, but they still lacked any temporal or geographical "Islamic" cutoff; Mughal and Hindu Indian art were displayed adjacently, as were pre and post-Islamic Persian pieces. This remained true for another fifty years.

Gallery D-3, 1926. Adjacent to the Great Hall balcony, this was the "entryway" gallery into the Near Eastern art collection for several decades. A significant 1923 carpet donation caused this room to be devoted exclusively to rugs—here an eclectic display of Persian, Spanish, and Turkish carpets shown side by side. It also held overflow concert audiences for the free symphony performances that for decades were offered regularly on the Great Hall balcony. This image shows some of the more than 7,800 concert attendees who, according to The New York Times (January 9, 1926) heard a program of Beethoven, Bach, Lully, Gluck, Tchaikovsky, Saint-Saens, Brahms, Strauss, and Smetana.

Gallery D-3, June 26, 1918. This view, looking southeast, shows the space before removal of the original heavy moldings (see next image).

Gallery D-3, 1949. The same room in 1949, with the simple sign "Oriental Rugs."

During Dimand's tenure, in addition to the six large galleries already in place (D-3, E 12–14, H-10, and H-20), the Metropolitan's Near Eastern galleries expanded to fill five more adjacent small galleries and two more large galleries, as well as several noncontiguous spaces.18 Many significant acquisitions allowed him to fill these spaces. One early acquisition was the James Ballard donation of carpets, which had been orchestrated by Dimand's predecessor, Joseph Breck, who succeeded Valentiner, and which went on display in 1923. Ballard, often described as the first modern carpet collector—in the sense that he attempted to collect systematically and comprehensively across many fields—generously allowed Breck19 to select 126 carpets from his collection; the selection ensured that the Metropolitan's Oriental carpet collection was unsurpassed. Ballard's May 22, 1922, letter to the Trustees read: "It is with great pleasure and much regret that I have the honor to present to the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the accompanying list of ancient carpets and rugs. . . . Much regret; because some of these rugs are very dear to me and in their incomparable beauty they have become a part of my soul . . . . The human inspiration which created these rugs seems to have been imparted to them."

Breck and Frances Morris, an associate curator of Decorative Arts, wrote the catalogue of the Ballard collection, which the Met published in an edition of two thousand and sold for $2.00 each. It was so popular that it remained in print for fifteen years. The Ballard and other donations also directly caused the rearrangement of the Near Eastern galleries to make possible the exhibition of more carpets.20

October 3, 1923. The Ballard carpet donation, seen here, prompted many changes in the Near Eastern Department displays: "There is a majesty and grandeur in these imperishable colors, mellowed but uneffaced by time and in the exquisite designs which render them a thing to love and cherish beyond any other form of art and when seen under proper light, each one seems bent on outdoing his neighbor in an effort to display every regal charm of beauty."21 The Mudéjar chest is below a large Ottoman piece. At lower left is the famous Ballard Ottoman prayer rug, and adjacent to the large Ottoman carpet are "Transylvanian" carpets also visible in later photographs. At right is an Anatolian prayer kilim; Ballard's collection was notable for its variety and inclusion of "peasant" or nomadic carpets as well as the lavish court-quality pieces prized earlier.

James Ballard

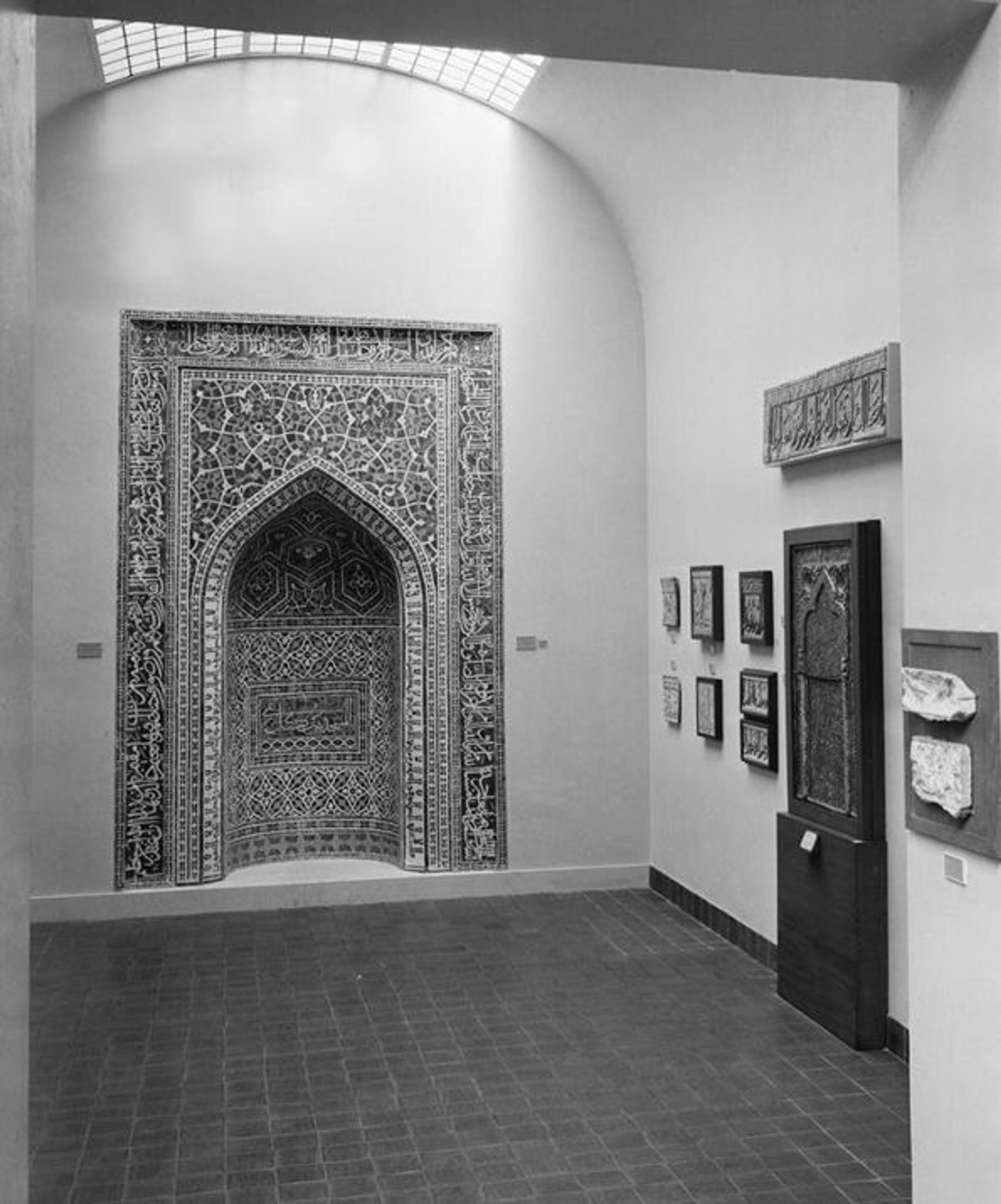

Despite the economic depression, the 1930s were productive years for Islamic art at the Museum.22 In particular, the number of special exhibitions on Islamic art topics increased exponentially. This was no doubt in part because of the January 1, 1932, establishment of a separate curatorial department called Near Eastern Art, chaired by Dimand. The new department's "ancient" and "Islamic" art continued to be displayed separately. Shortly thereafter, the Museum's only Islamic-era archaeological work began at Nishapur, Iran, the legendary home of the famous Persian poet, philosopher, and mathematician Omar Khayyam. The Metropolitan arrangement with the Iranian government was to divide the excavation finds equally; a coin toss determined which half came to the Metropolitan and which stayed in Tehran. Visitors to the Museum would have seen for the first time the finds from the 1936 Iranian expedition, including objects from the Sabz Pushan mound, in a temporary exhibition that opened October 16, 1937.23 The Nishapur materials went on permanent exhibition in 1939, when the Museum also acquired and put on display its celebrated fourteenth-century Isfahan tile mihrab from the Madrasa Imami.

The Near Eastern Department's newly built special exhibition hall, Gallery E-15, at its opening, October 25, 1937. This photo shows the first display of material from Nishapur, Iran. Included were Samanid stucco panels dated between 961 and 981 from a courtyard dado in Sabz Pushan and photographs of excavation sites. Because it was built into a light well, the gallery had glass ceiling panels that could be opened, as seen here.

Gallery E-14A, September 12, 1939. This photograph shows the first display of the 1354 mihrab from Isfahan, which served as the principal symbol of the department from 1939 until 1975 and remains an iconic piece. Above the door is part of a page from the Qu'ran of the Timurid prince Baysunghur, from Samarkand, and at right, Ilkhanate tile friezes and a leaf from the Shahnameh of Shah Ismail II.

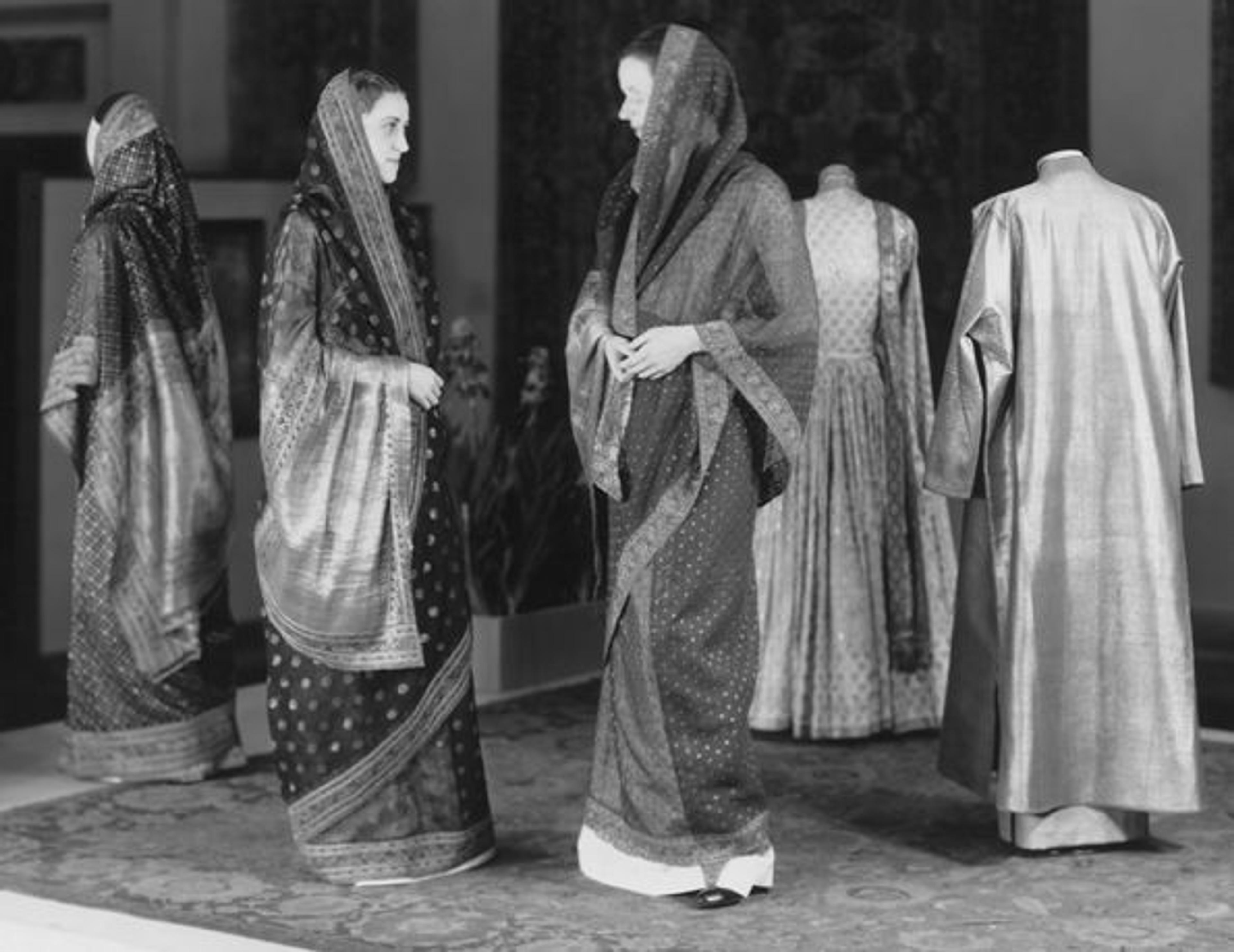

The summer 1935 exhibition Oriental Rugs and Textiles included objects from nineteen lenders. It was unique in using live models to display Near Eastern costumes, and also in being advertised in ladies' clothing stores such as Wanamaker's. As was the case until the 1960s, both "Islamic" pieces—here, kaftans—and non-Islamic Indian pieces—here, saris—were often displayed together.

Poster for the 1935 exhibition Oriental Rugs and Textiles. Between the end of World War I and 1946, the Museum presented twenty-seven special exhibitions with an Islamic focus. Each had a special poster designed by the Museum's graphic arts department to echo the motifs in the art.

Another view of the 1935 Oriental Rugs and Textiles exhibition. The Museum's Nigde carpet is at right and a Persian velvet piece and a Kashan carpet are at left.

October 14, 1933. This view of the Islamic Miniature Painting and Book Illumination exhibition (on view October 9, 1933–January 7, 1934) also shows rugs from the Museum's collection.

World War II until 1975: A Separate Identity for Islamic Art

World War II inaugurated an age of rapid change in the display of Islamic art, a reflection of much greater sophistication among the viewing public and of significant evolutions in the emerging scholarly field of Islamic art history.

The 1941 bombing of Pearl Harbor affected the entire Museum by causing the evacuation of fragile art, including many Oriental carpets, and the closure of some galleries owing to lack of staff. Temporary exhibitions filled part of the display gap. In 1942, for example, the indefatigable Dimand, ever alert to a chance to make his collections topical, informed Museum Director Francis Taylor that the "great interest in North Africa at present" (due to the battle of El Alamein) had prompted him to "install . . . an exhibition of Moroccan and Algerian textiles."24

Gallery E-13, May 18, 1943. Most of the Museum's large and fragile objects were in storage for fear of air raids; but this gallery was unaffected, and teaching use of Islamic materials—here Mughal miniatures from the Alexander Smith Cochran Collection—continued unabated. A Kashmiri carpet is on the wall at left.

By early 1944, "competent military and naval authorities" confirmed that it was safe to return stored art objects to the Museum,25 and on November 15, 1944, two temporary Islamic loan exhibitions celebrated that return. For one, Enameled Islamic Glass of the 13th and 14th Centuries, Gallery E-15 was painted a striking dark blue with spotlights focused on the glass so that the objects shone like stars against the darkness. The other, in adjacent galleries, featured twenty "Great Rugs of the Orient."26

Gallery E-15, December 26, 1944. This gallery housed the exhibition Enameled Islamic Glass of the XIII and XIV Centuries (on view November 15, 1944–February 15, 1945).

Gallery D-3, December 2, 1944. The exhibition Great Rugs of the Orient celebrated the return of objects from storage when the danger of air raids was deemed over.

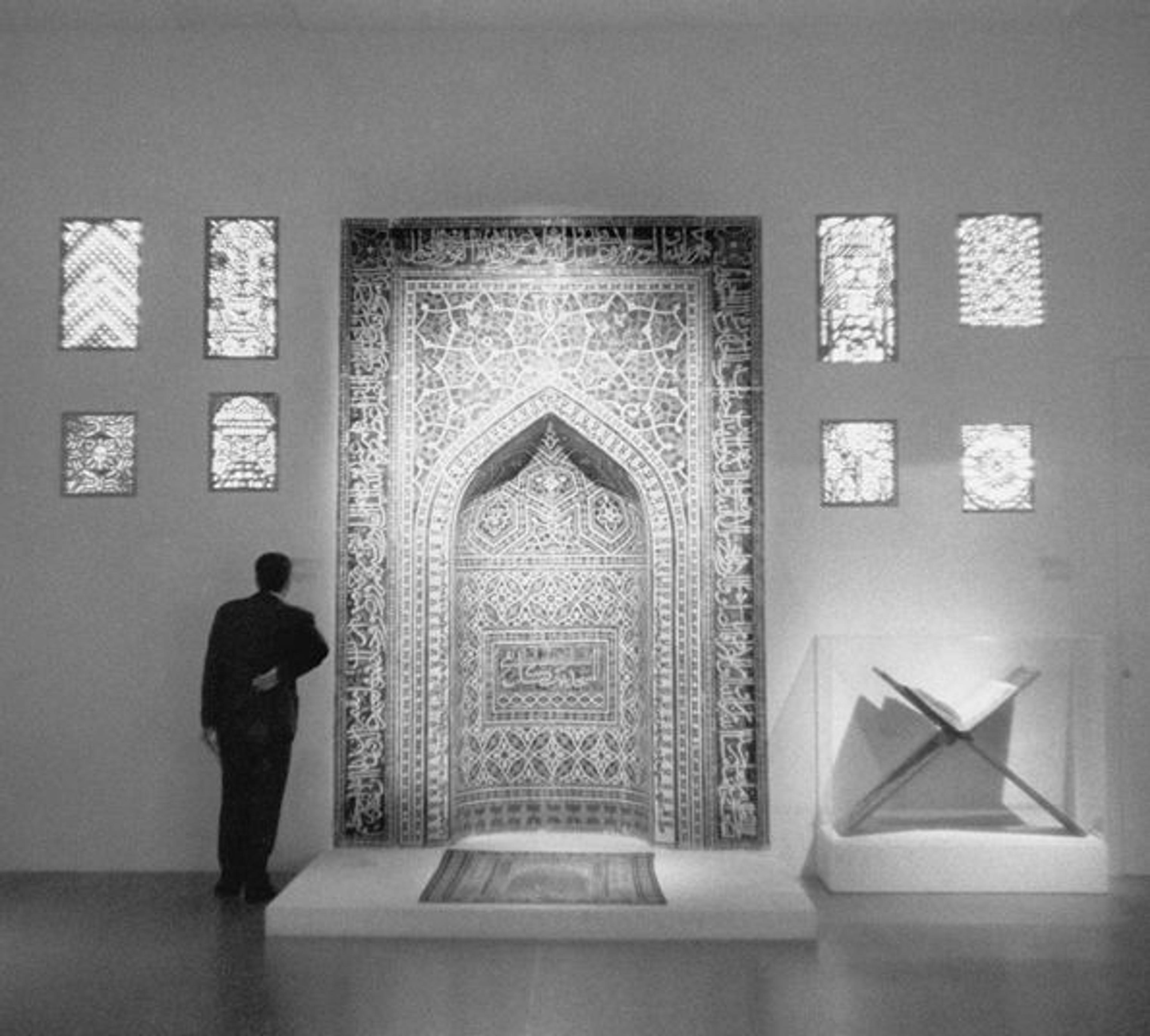

In 1947, however, all the Near Eastern galleries closed to make way for shows from other departments. The collections were reinstalled "permanently" in 1949 in their former location: fourteen large and small galleries in Wings D, E, and H. For the first time, the press releases and signage consistently identified the art on display as "Islamic."27 Although the 1949 installations were the finest presentations of Near Eastern art that the Museum had ever offered, they only lasted a decade. In 1958 the twelve E and H galleries closed because of structural concerns about the floor and roof, and by 1962 the two remaining D galleries had also been closed. Most of the collections went into storage for almost fifteen years. A single temporary Islamic gallery remained open from 1965 until 1972. It was chronologically arranged and contained mostly small objects, a few carpets, and one monumental piece—the fourteenth-century Isfahan tile mihrab. This was the Museum's sole permanent display of Islamic art until new galleries were opened in 1975.28

This single Islamic gallery was open from 1965 until shortly before the new Wing K galleries opened in 1975. As the sole permanent display of the art of the newly established curatorial Department of Islamic Art, it "show[ed] as many important, relatively small-scale objects as will fit into the new room," in the words of Ernest Grube, Associate Curator in Charge of Islamic Art [The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin New Series, Vol. 23, No. 6, "Islamic Art" (Feb. 1965), p. 197]. Visible are the fourteenth-century Persian mihrab, Ottoman windows of the eighteenth century and a fourteenth-century Persian Qu'ran stand. Photograph by Gary Winogrand, 1965

During this time, the collection itself also grew tremendously. One highlight was the 1943 purchase of the "Emperor's carpet," reputedly presented by Peter the Great to the Habsburg emperor Leopold I before eventually going into the collection of Edith Rockefeller McCormick, from whose estate the Museum bought it. Another was the Kress Foundation's 1946 donation of the Anhalt medallion carpet, reputedly abandoned by the Grand Vizier Kara Mustafa at the gates of Vienna in 1683 (Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin, New Series, Vol. 5, No. 2, Oct. 1946, p. 49). The Anhalt carpet hung from the Great Hall balcony when it was first acquired. Between 1957 and 1973, Joseph McMullan, who had begun his patronage of the Museum modestly in the 1930s, gave and bequeathed more than one hundred additional carpets, most of which were displayed for the Museum Centennial in 1970. For this unusual exhibition, the American Museum of Natural History lent a complete Turkmen tent furnished with carpets, and the government of Iran sent the master weaver Mahindokt Afsari, who wove a Senneh knot carpet with 324 knots per square inch on a vertical loom during the course of the exhibition (Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin, New Series, Vol. 29, No. 2, Oct. 1970, p. 84).

In the area of paintings, the Department of Islamic Art purchased thirty-nine leaves from the Shah Jahan album in 1955 and in 1970 received a donation from Arthur Houghton of seventy-six folios with seventy-eight illustrations of the great Shahnama of Shah Tahmasp; these were displayed in 1972 in the exhibition King's Book of Kings, the last use of the Wing K galleries before they were reconfigured for the 1975 Islamic Department galleries.

The single largest acquisition by the Department of Islamic Art during this period was undoubtedly the donation by the Kevorkian Foundation of what was then called the Nur-Al Din Room, which had been purchased in Syria in the 1930s by the dealer Hagop Kevorkian and disassembled and stored for decades. Now known as the Damascus Room, it came to the Museum in 1970 in "hundreds of pieces." A few years later, additional pieces were located and donated, and in 1975 the room was assembled in Gallery K-27 as part of the 1975 installation of the permanent collection of Islamic art. (For the 2011 installation, the room was once again disassembled and moved.)

The 1975 Galleries

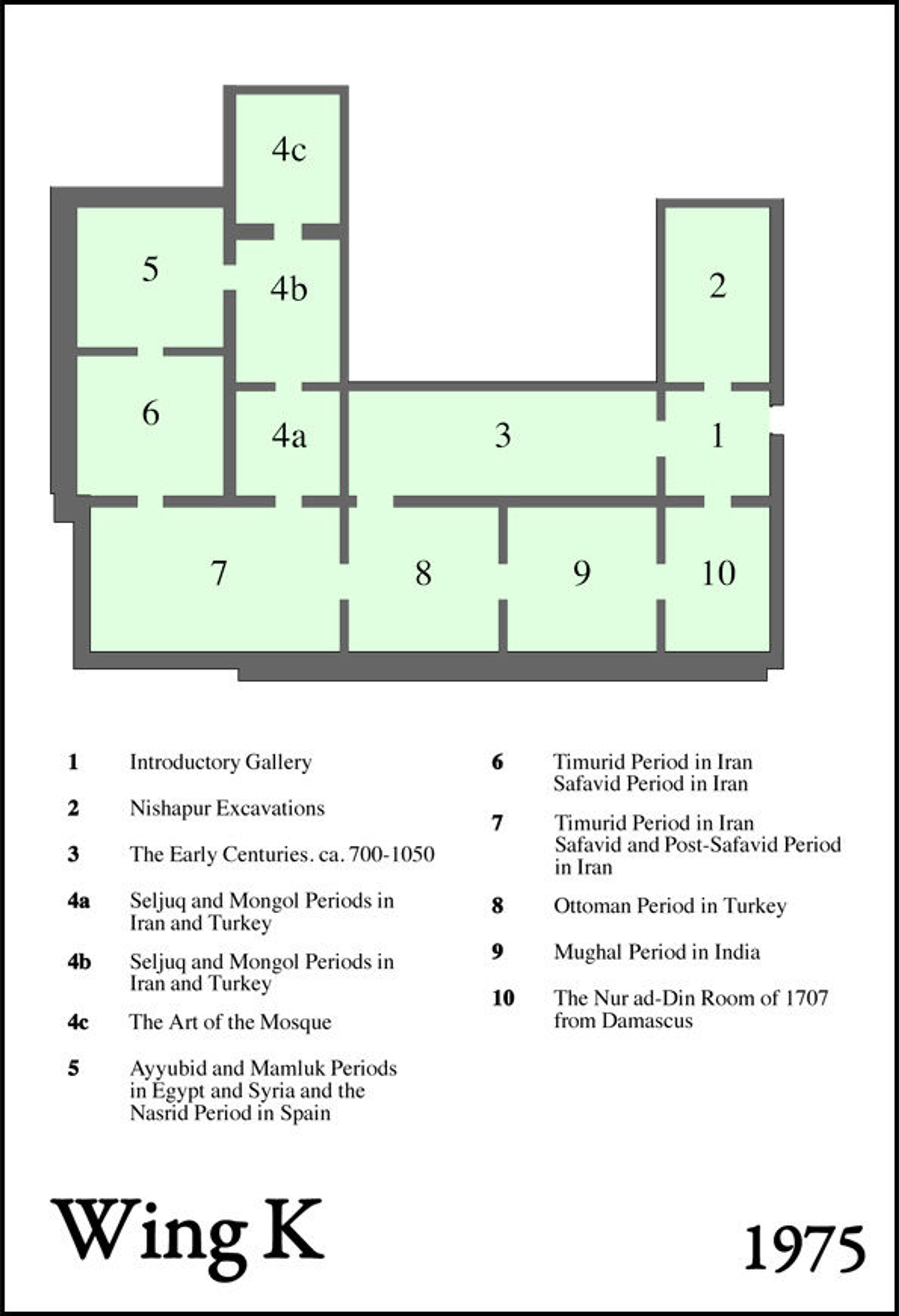

Wing K, 1975

Planning for the 1975 installation of ten Islamic art galleries had begun in 1957, but it wasn't until 1971 that their final location on the second floor of Wing K was determined.29 Arthur Houghton, Chairman of the Museum's Board of Trustees and a strong supporter of the new department, made the installation possible.30 The original schedule specified that "the planning stages to design the exhibition in these areas will be from July 1, 1971, to January 1, 1972" with installation starting January 1, 1972, and the gallery opening on April 1, 1972. The galleries were to be empty and available for work starting in September 1971.31 Perhaps not surprisingly, this ambitious schedule proved unrealistic: the emptying of the galleries was delayed by a year for the Shahnama exhibition; the new galleries opened in September 1975.32

Gallery K-30, "Timurid and Safavid Iran," in 1975. The room illustrates the minimalist 1970s aesthetic that marked this installation. The "Seley" carpet is in the center, with sixteenth- and seventeenth-century Persian carpets to the left. The room retained its original McKim, Mead & White skylight.

The 1975 galleries opened during the curatorship of Dr. Richard Ettinghausen, a scholar who also served as consultative chairman of the Department of Islamic Art from 1969–79. Dimand, who remained active as Curator Emeritus into the 1970s, also assisted in the organization.33 At the time, the galleries represented the largest permanent exhibition of Islamic art ever shown in the Western hemisphere. They were organized along the lines of the pre–World War II displays in the Kaiser-Friedrich Museum in Berlin, where Ettinghausen had trained. The galleries displayed art from the Seljuk and Mongol eras, followed by rooms arranged by country and region. Separate from these were the Nur al-Din Room and the Nishapur gallery, which provided the viewer with a sense of Islamic architecture, both interior and exterior. These installations lasted into the twenty-first century with only minor changes and provided a fitting culmination for the first century of Islamic art displays at the Metropolitan.34

The Nur Al-Din Room, 1975

May 9, 2009. The fountain from the Nur Al Din/Damascus Room is winched by hand down a corridor from its 1975 home to its 2011 home. The gentleman with the broom is sweeping cornstarch under the cement slab, a low-tech but totally effective way to lubricate the floor.

The Twenty-first Century

Since its inception, the Department of Islamic Art's exhibitions and displays have evolved in ways that mirror new areas of focus not just for scholars, but also for collectors. Early donors and researchers prized court-quality works—especially textiles, ceramics,35 and painting—from Persia, the Levant, and Egypt, popular "exotic" destinations in the early twentieth century, when excavations excited the public imagination.

As early as World War II, however, new trends began to emerge. A showing of "Peasant and Nomad Rugs of the Caucasus" held at the Museum in 1943 presaged the enormous interest in geometric and flat-weave pieces that is now current. "Tribal" jewelry from the Islamic world, which was little appreciated in the Victorian and Edwardian eras, is also now collected by the Department; today the popularity of these pieces rivals that of Mughal gold and precious jewels.

Since then, while continuing the cutting-edge research in the traditional Middle Eastern areas of Museum expertise, the Department has also focused on other areas including India, Ottoman Turkey, and Andalusian Spain—almost thirty special exhibitions on those three areas alone since World War Two. (The Department's ability to mount these exhibitions was greatly enhanced in 1982 when the Kevorkian Foundation funded the opening of a permanent gallery for mounting Islamic Department temporary exhibitions.) In recent decades, archaeological work in the Middle East has become more difficult. At the same time, oil-financed development in the Arab world has expanded the demand in those countries for examples of their own art, and worldwide sensitivity to clandestine trade in antiquities has meant that the Museum cannot as easily purchase objects directly from the sources.

But as a result of the British presence in India until 1947, scores of collections of Indian art with well-documented histories of export and ownership going back many decades have come to light. Similarly, post-Ottoman Turkey36 has long supported studies on Ottoman subjects. Andalusia has been popular in this country since the days of Washington Irving; art of the era has been dispersed in western Europe for centuries, and the Museum's seminal 1992 exhibition Al-Andalus directly led to the inclusion of a room in the new galleries for the art of Islamic Spain (Gallery 457).

As the 2011 galleries of the Art of the Arab Lands, Turkey, Iran, Central Asia, and Later South Asia make their debut, the Department of Islamic Art looks forward to introducing a new generation to the beauty of the works on view, and to continuing the Museum's 130-year history of displaying these treasures.

March 1, 2011. Craftsmen from Fez execute traditional plasterwork, woodcarving, and Zellij tilework based on a pattern in the Alhambra, in the Moroccan Court, Gallery 456.

Islamic Art Displays, 1880–2011 1880–1910 Wing A, first floor Rooms E, W, Z 1888 Wing B, second floor room Q, and Wing A, Room H 1888–1906 Wing B-19 1891–94 B-15 Moore Collection 1894–1910 C-26 Moore Collection 1909 C-22 Textile study room (basement) 1910 E-12–14 (closed 1947–49; 1958–65) 1912 D-3 added; closed 1962 with D-4. E-12A and E-14A built 1913–58 H-10 1914–58 H-23 textile study room 1914–26 C-38 Altman collection Oriental rugs 1915 E-13-A, C 1916 H-20; closed 1958 1925–58 H-15, 16 for Near Eastern embroideries 1926–53 K-33 Altman rugs 1936–58 E-15 built 1939–58 H-8 1947 D-4 for Indian art, until 1962 1965 Gallery 2-72-G (formerly E-12–14) opened. Closed 1973 1975 K-23-36, 41 (Galleries 1–10) opened 1980s K 37-40 storeroom and office space opened 2011 New galleries opened

[1] The description of the works now in the Department of Islamic Art has changed over time, from "Persian" to "Mohammedan" to, in 1932, the jawbreaking "Division for Art of the Islamic Near East, comprising Moorish Spain and North Africa, Egypt Under the Arabs, Turkey in Europe, the Caucasus, Asia Minor, Syria, Mesopotamia, Arabia, Persia, West Turkestan, Afghanistan, India, Indonesia, and Indo-China." Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin, Vol. 27, No. 1 (Jan. 1932), pp. 18–19.

[2] See, e.g., letter of William Sloane Coffin (Museum Trustee) to Curator Joseph Breck, October, 14, 1931: "It may be necessary eventually to separate the Persian and the Assyrian and have different experts in charge."

[3] A well-known example of this taste is Olana, the "Moorish" house built on the Hudson by Frederick Edwin Church in the 1870s. While Church described Olana as "Persian," it contained Chinese, European, modern Mexican, and pre-Columbian art elements along with Near Eastern items of every era. The chimneypots are Japanese teapots.

[4] The Metropolitan's first two works of art from the Islamic world came through the 1874 public purchase of "Cypriote" antiquities excavated by the Museum's dashing first director, Luigi di Cesnola; they went unrecognized for decades. When the Museum's Central Park building opened in 1880, there were also Islamic textiles that had been collected by the wife of the Orientalist painter Andrew MacCallum on the couple's Middle Eastern journeys in search of picturesque subjects. The MacCallum collection was exhibited at the Museum in 1877, offered for sale for $5,000, and acquired for the Metropolitan by an anonymous donor. Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin, Vol. 19, No. 8 (Aug. 1914), pp. 178–81; The Art Journal New Series, Vol. 4 (1878), p. 32.

[5] Museum Handbook No. 5, "Oriental Porcelains" 1877–83, pp. 35–36; see also Ernest Ingersoll, A Week in New York. New York: Rand McNally and Co., 1891.

[6] The Moore collection was displayed together until 1912—first in room B-15, then in C-26, then in E-12, and after construction of Wing H in 1913, with other objects in galleries H-10 and H-20 (later H-21). This last move was possible because Moore's executors showed an exemplary willingness to accept the Museum's suggestions to group, for example, the Moore textiles "with other similar objects for the greater convenience and benefit of students." Letter, January 19, 1906, from Edward C. Moore Jr. to Edward Robinson, Museum Assistant Director.

[7] Twenty years later, Altman's residuary legatee and trustee Michael Friedsam, who had inherited many of his Near Eastern decorative arts objects, in his turn bequeathed his entire collection to the Museum.

[8] The 1910 exhibit cost approximately $4,000 to mount, including $3,000 for the fully illustrated catalogue, a mere $216.30 for transporting the loans to the Museum from Europe and all over the U.S.; a reasonable $505.20 for insurance, and $278.50 for fabric and labor to rehang the walls of the exhibition room with 210 yards of gray Arras cloth. The Museum paid an additional $100 to Bloomingdale's department store to rent twenty-six "pyramidal bay trees" as decorations, and Bloomingdale's was responsible for training Museum staff to water the trees.

[9] The completion of Wing E made it possible, in early 1910, for the Department of Decorative Arts to separate Eastern from Western object displays. Galleries E-12–14 became the nucleus of the Museum's Near Eastern displays until the 1975 galleries opened; they were supplemented over time by D-3 and D-4 to the south and H-8, -10, -20, and -21 to the north. (Today all of these rooms and many more house Asian art.) Valentiner first arranged Near Eastern Art in the E galleries between 1907 and 1910: E-12 for the Moore collection, E-13 for Persian art beginning with fourth-century Sassanian, and E-14 for "Saracenic Art, Syria, and Asia Minor." Small extensions off of the three main galleries, denominated 12-A, 13-A, -B, and -C, and 14-A, were added in 1912, and gallery E-15 in 1936. (These additions were obliterated by the construction of the Grace Rainey Rogers Auditorium in the 1950s.) Even at this early time, Valentiner strove to achieve the most modern in museum display techniques: "The new rooms [E-12A and E-14A] are built with vaulted ceilings, flagged floors and walls finished in a rough cast plaster, very slightly tinted, in an endeavor to procure a background suggesting the plaster and color wash found in native houses throughout the Near East. The cloth wall-covering in Galleries E-12, -13, and -14 was replaced by a similar plaster surface so that all five rooms now show a harmonious and related treatment" Report of William Valentiner on the Department of Decorative Arts for the Year 1912. By the early 1920s, when the Moore collection moved, Gallery 12 was "Persian or Asia Minor material of the sixteenth century or later." Galleries 12-A and 13-A–C contained mostly non-Islamic Indian arts; Gallery 13 contained Mughal and Hindu miniatures, textiles, and metalwork of the Islamic. Gallery 14 contained Near Eastern art dating before 1500, including mosque lamps donated by JP Morgan and ceramics from Syria, Egypt, and Persia, miniatures from the Alexander Smith Cochran Collection, and the fourteenth-century Koran stand. 14-A contained Persian pottery, mainly Rhages, and tiles. Gallery D-3 contained twenty representative examples of Near Eastern and Indian rugs or unusual beauty and interest. Guide to the Collections, 1922.

[10] The Museum's Brief Guide to the Collections in 1947, for example, described the Near Eastern galleries as "Near Eastern Art, embracing the decorative arts of the Muhammedan countries."

[11] Indeed, in 1918 the Metropolitan created a position for "Associate in Industrial Arts" to facilitate use of the Museum as a resource for manufacturers, artisans, and designers. The first associate, Richard Bach, immediately organized the unusual Plant Form in Ornament joint exhibition with the New York and Brooklyn Botanical Gardens and the New York Aquarium, designed as an opportunity for craftsmen to study applied art. For the exhibition, the Museum contributed thirty-three Islamic items and the Botanical Garden and New York Aquarium contributed flowers and fish in staggering numbers, since the mortality rate for both was high! This 1919 exhibition was extremely successful and was enlarged and repeated in 1933, again as an "industrial art" exhibition particularly rich in Islamic objects.

[12] In part owing to the discouragement of figural art in sacred contexts, Islamic decorative arts had been highly developed for many centuries, so when more of this art became available to viewers in the early twentieth century, the very high quality of what was available has been credited with helping to elevate the stature of decorative arts in general in the art world. See Art Treasures of the Metropolitan, (New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1952), p. 197.

[13] As early as 1939, the WPA Guide for New York credited the Islamic paintings exemplified by the Alexander Smith Cochran Collection as an inspiration for Matisse. Works Progress Administration New York City Guide (New York: Random House; 1939), p. 372.

[14] Letter, February 28, 1902, from Patrick Reynolds, Museum Registrar, to Kelekian. Kelekian provided a "certification" dated March 2, 1902, that the pieces were "very good, mostly 16th century."

[15] Cochran, heir to a carpet fortune, also donated important carpets to the Museum.

[16] WWI itself caused some disruption. It completely halted Museum acquisitions and significantly delayed completion of Wing K, as stone for cladding could not be delivered from Europe owing to U-boat attacks. In addition, the outbreak of war in Europe in August 1914 caught the energetic curator Dr. Valentiner on a buying trip to Europe; his Near Eastern purchases were delivered only after the Armistice. Like other Museum curators of European birth, Dr. Valentiner felt compelled to serve in the armed forces of his native country; it is pleasant to note that these men received leaves of absence and were treated with unfailing courtesy then and later by the Museum. See, e.g., letter from Robert de Forest, Museum President, September 27, 1916, to Lawrence Abbott, President, the Outlook Company; letter Edward Robinson, Museum Director, to Dr. Valentiner, March 20, 1917.

[17] The Handbook, first published by the Metropolitan in 1930 and reissued several times in the ensuing decades, was the first guide in English that identified an Islamic aesthetic; such was its success that it was translated into Persian and Arabic.

[18] In 1936, Dimand arranged to build Gallery E-15 to provide a space for special exhibitions, akin to today's Kevorkian Gallery, and in 1939 he annexed Gallery H-8 on the first floor to display Coptic, Abbasid, and Iranian objects, including some more from Nishapur. Of the Near Eastern Department space, one large and four small galleries were exclusively Indian art; the remaining seven large (and one small) gallery were predominantly, though not exclusively, dedicated to the display of Islamic art.

[19] Breck later became Director of the Cloisters and Acting Director of the Metropolitan. He established the Department of Near Eastern Art and created the separate "Division for Art of the Islamic Near East." Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin, Vol. 27, No. 1 (Jan. 1932): pp. 18–19.

[20] Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin, Vol. 19, No. 11 (Nov. 1924): pp. 265–267.

[21] Letter of James Ballard to Museum Trustees, May 20, 1922, on the occasion of his donation.

[22] A sign of the economic times was a modest donation of $10 received in 1937 from one Joseph McMullan, who wrote to Henry W. Kent, Museum Secretary, that "some day I may be in a position to do something more substantial, particularly, I hope in the sadly neglected field of near eastern art, whose greatness and significance is gradually dawning on our western minds." Twenty years later, inspired by Ballard, and having assembled perhaps the "greatest private collection of oriental carpets in the country," then valued at one million dollars, McMullan gave his first carpet to the Metropolitan; during his lifetime he donated forty-two more and at his death he left the Department of Islamic Art fifty-nine additional carpets. See New York Times, Nov. 25, 1957; Museum press release, June 1970, concerning the McMullan Collection; Memorandum of Marie Swietochowski to Ashton Hawkins, November 8, 1973.

[23] New York Times, Oct. 16, 1936, p. 21.

[24] December 3, 1942, Internal Memorandum from Dimand to Francis Henry Taylor, Museum Director 1940–55.

[25] See, e.g., letter December 7, 1943, from Taylor to John S. Burke, Esq., trustee of the Altman Foundation.

[26] New York Times, November 15, 1944, p. 23.

[27] In 1956, the Museum created a separate department of Ancient Near Eastern Art (defined as art of the region before the death of Alexander the Great in 323 B.C.), and thereby left Islamic-era art as the primary focus of the Department of Near Eastern Art. From 1959–63, the Near Eastern and Ancient Near East departments were again briefly combined under Charles Wilkinson, a scholar of diverse interests and accomplishments who had led the Museum's Nishapur excavations in the 1930s. Wilkinson's retirement in 1963 precipitated the formation of the independent Department of Islamic Art.

[28] See, e.g., Feb. 11, 1971, memo from Richard Ettinghausen to Thomas Hoving, noting that more than eighty percent of the Islamic art collection had been off display for more than ten years.

[29] See, e.g., New York Herald, September 8, 1957. As late as 1968, the plan was for the new Islamic galleries to open in the same location where the Near Eastern galleries had been—"north Wing, second floor"—and in time for the Museum Centennial in 1970. Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin, Oct. 1968, p. 103.

[30] The original budget was less than half a million dollars, not including the cost of installing the Damascus Room, which the Kevorkian Foundation underwrote. The final cost exceeded the original budget by about twenty percent.

[31] See April 29, 1971, memo from Marilyn Jenkins to Department of Islamic Art. The 1972 Museum Guidebook was published with a close-to-accurate diagram and description of the Islamic galleries as they eventually opened in 1975. However, between 1972 and 1975 there was no permanent display of Islamic department objects at all.

[32] May 5, 1971, letter from Thomas Hoving to Marjorie Kevorkian.

[33] As had Ernest J. Grube, who led the department after Wilkinson's retirement and before Ettinghausen's appointment.

[34] The 1975 galleries were disassembled in 2004. Navina Haidar, curator in the Department of Islamic Art, has had primary responsibility for the 2011 project since its inception, in association with Daniel Walker, Department Chairman through 2005, Michael Barry, Consultative Chairman 2005–08, Sheila Canby, Department Chairman since 2009, and many others.

[35] As early as 1880 the Museum presented a special exhibition of "Oriental Porcelains." Between 1921 and 1931 there were five special exhibitions of Islamic carpets and textiles, and between 1933 and 1941, there were four special exhibitions exclusively of Islamic painting.

[36] The Islamic Department does not collect contemporary art; the general cutoff date for pieces being considered for acquisition is the end of the Ottoman Empire.