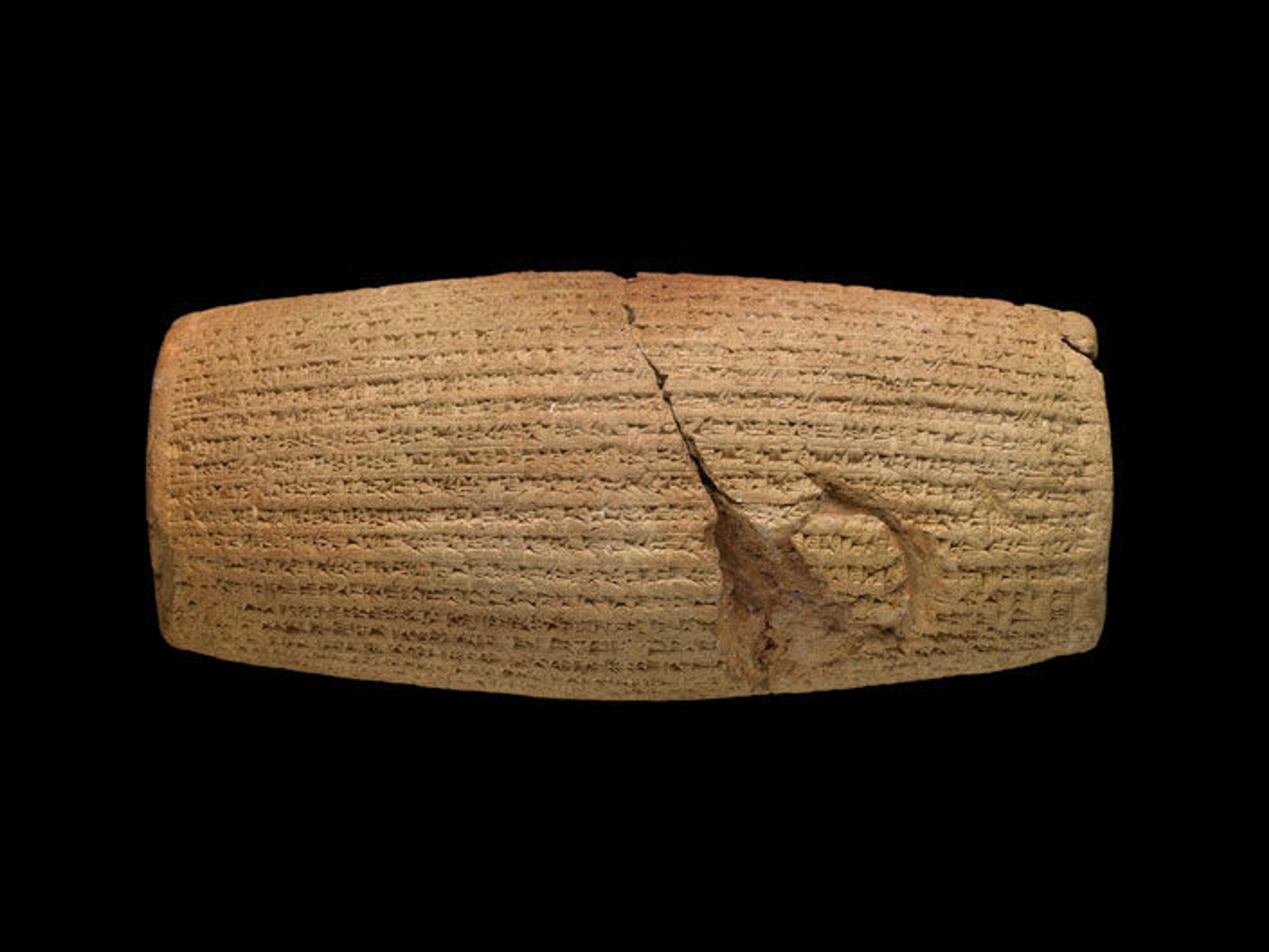

The Cyrus Cylinder. Baked clay. Achaemenid, 539–538 B.C. Excavated in Babylon, Iraq, in 1879. British Museum 90920. © Trustees of the British Museum

«The Cyrus Cylinder, currently on display in the exhibition The Cyrus Cylinder and Ancient Persia: Charting a New Empire (June 20–August 4, 2013), is a document of unique historical significance. It records the Persian king Cyrus' conquest of the city of Babylon in 539 b.c., and his proclamation that cults and temples should be restored, their personnel allowed to return from Babylon to their home cities.» When the Cylinder was discovered in the late nineteenth century, scholars immediately realized that the text accorded well with the biblical account, according to which Cyrus allowed the population of Jews in Babylon—deportees from Judah and their descendants—to return to Jerusalem, and supported the rebuilding of the Temple there. Cyrus' act was remembered through the Bible, and in later tradition he was celebrated where former kings of Babylon were reviled.

Cyrus was even more fortunate in his legacy than this, since a second tradition reinforced a positive image of the Persian king. Xenophon, a Greek soldier and scholar writing in the fourth century b.c., produced an idealized biography, the Cyropaedia, or Education of Cyrus. The work was based on the idea that Cyrus, having succeeded in creating and holding the largest empire ever known, with its diverse peoples and languages, must have possessed uncommon gifts as a leader, and that it was therefore worthwhile to study his successes. The Cyropaedia is highly fictionalized, and the Cyrus it presents very much adapted to Greek tastes and ideas of virtue, but Xenophon did have first-hand knowledge of the Persian empire and court of his own time. He drew on this experience, and quite possibly on Persian court tales of Cyrus, in producing his account.

As presented in the Cyropaedia, Cyrus is a model of virtue, and thus a leader by example, but also a shrewd military strategist and politician. This portrait certainly earned important admirers in antiquity, notably Alexander the Great and Julius Caesar, both of whom saw lessons for rulers in Xenophon's Cyrus. Late Medieval and Renaissance scholarship would revive this role for the work, as a key text in the genre of "mirrors for princes"—works with instructional value for good government. The most famous Renaissance guide for rulership, Macchiavelli's The Prince, itself drew heavily on the Cyropaedia. Unsurprisingly, Cyrus retained a strong positive image: a sixteenth-century depiction, included in the exhibition, shows Cyrus as one of four great rulers of antiquity:

Adriaen Collaert (Netherlandish, Antwerp ca. 1560–1618 Antwerp) after Maerten de Vos (Netherlandish, Antwerp 1532–1603 Antwerp). Cyrus, King of Persia, from Four Illustrious Rulers of Antiquity, 1590s. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, The Elisha Whittelsey Collection, The Elisha Whittelsey Fund, 1949 (49.95.1570)

The other portraits in the series show Ninus (the mythical eponymous founder of Nineveh), Alexander, and Julius Caesar. More recent admirers of the Cyropaedia have included Montesquieu, Thomas Jefferson, and Benjamin Franklin—democratic political philosophers who continued to see great value in Xenophon's depiction of statecraft as practiced by a benevolent dictator.

Alongside this tradition, the biblical image of Cyrus as a liberator remained strong. Drawing on the powerful language of the Old Testament prophets, the Book of Revelation in the New Testament uses the event of Cyrus entering through the open gates of Babylon as a metaphor for the Apocalypse itself; here it is a much more dramatic and violent Fall of Babylon that gives way to the heavenly New Jerusalem. This apocalyptic Fall of Babylon engendered a rich tradition in art, and one in which references to the politics of the present occur frequently, as in the example included in the exhibition:

Philips Galle (Netherlandish, Haarlem 1537–1612 Antwerp) after Maarten van Heemskerck (Netherlandish, Heemskerck 1498–1574 Haarlem). The Fall of Babylon, 1569. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, The Elisha Whittelsey Collection, The Elisha Whittelsey Fund, 1965 (65.587.8)

In such images, the maligned "king of Babylon" means not Cyrus but his Neo-Babylonian predecessors: either Nebuchadnezzar, who was responsible for the deportations that had originally moved a large part of the population of Jerusalem to Babylon, or the last native king of Babylon (in fact Nabonidus, but in biblical tradition his son, Belshazzar). Where Cyrus is described it is in his Old Testament role as a liberator. A silver plaque produced by Johann Andreas Thelot depicts him presiding over the return to Jerusalem.

Johann Andreas Thelot (1655–1734). Cyrus Freeing the Jews from the Babylonian Captivity, late 17th century. German (Augsburg). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Rogers Fund, 1948 (48.68)

The significance of this return is enormous, though it should also be remembered that many Judaeans chose to remain in Babylon, marking the beginning of two and a half thousand years of Jewish tradition in Iraq.

The rediscovery of the Cyrus Cylinder, in 1879, gave a physical focus to admiration for Cyrus, and also generated excitement because of its close correspondence to the proclamation described in the Bible. The Cylinder has taken on an iconic status in Iran, and also holds considerable symbolic importance in Israel. Today, a copy of the Cylinder is displayed in the United Nations in New York. Claims that the Cylinder represents the first "charter of human rights" are wide of the mark—if anything, the document is a statement of benevolent kingship—but its symbolic value as a modern icon of ancient religious tolerance remains enormous.