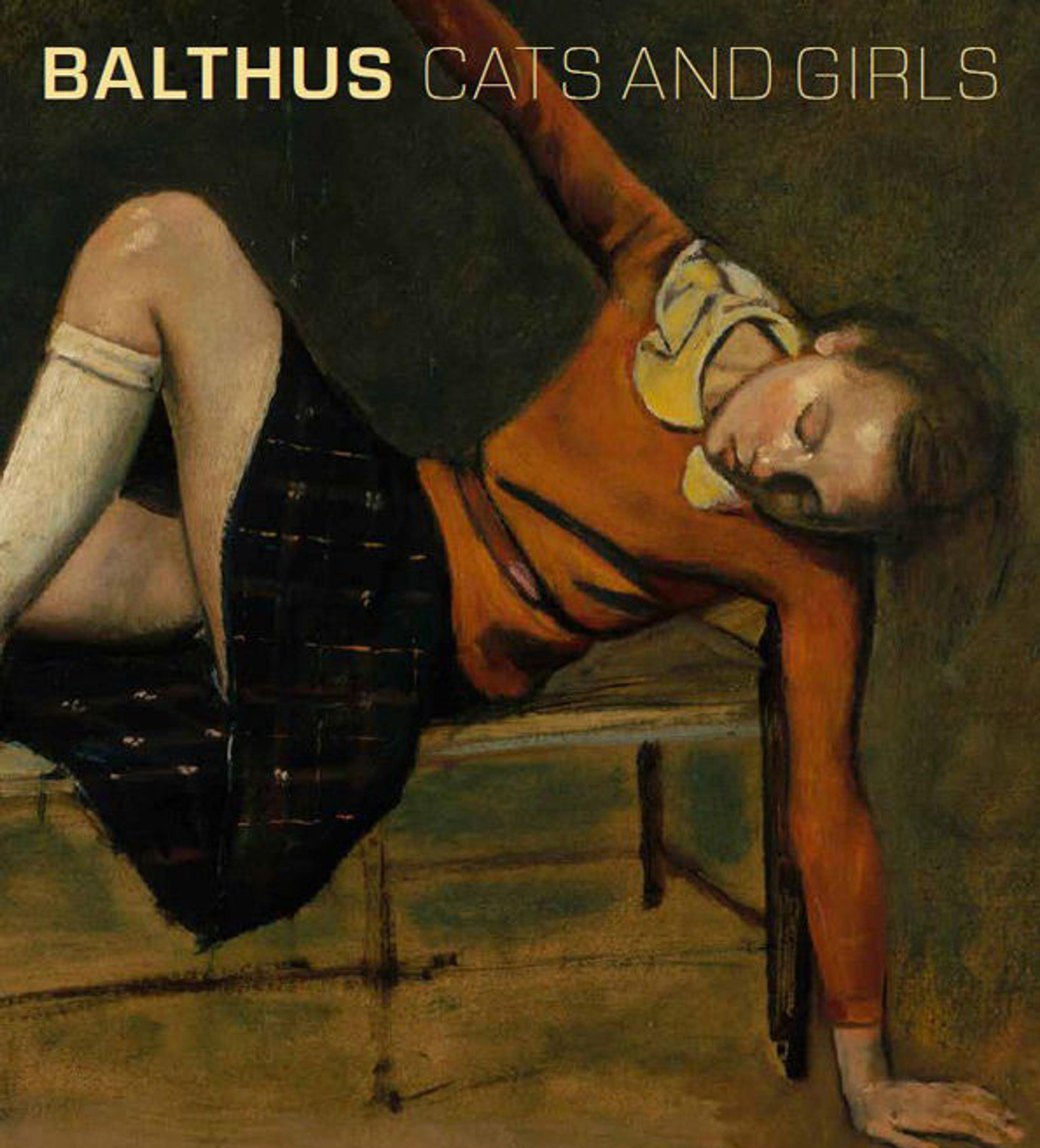

Balthus: Cats and Girls, by Sabine Rewald, features 120 illustrations and is available in The Met Store.

«With less than a month left to see the exhibition Balthus: Cats and Girls—Paintings and Provocations at The Metropolitan Museum of Art, I sat down with Sabine Rewald—Jacques and Natasha Gelman Curator in the Department of Modern and Contemporary Art, and author of the accompanying exhibition catalogue—to discuss her many years of fascination with Balthus, as well as her latest research that has brought such a renewed richness to the artist's subjects.»

Nadja Hansen: You have already written two other publications about Balthus. What keeps drawing you back to him as a subject?

Sabine Rewald: The first was the dissertation from my graduate work in 1984, on which I based the Met's 1984 catalogue, but the other publication came about not at all of my own volition. I was working on preparing my 2006 exhibition and catalogue, Glitter and Doom, and I felt that the Otto Dix portrait of Dr. Hans Koch was crucial to the show; I just had to have it. The Museum Ludwig in Cologne agreed to loan it to me if I organized an exhibition and wrote a catalogue for them about Balthus. It was an exchange really. I was happy to do it, but it was more of a retrospective—not a book sharing my recent personal research. There hasn't been an exhibition on Balthus in America in thirty years, meaning there is a whole generation that hasn't been exposed to him by a museum exhibition.

I didn't want to do a boring survey, but something smaller, focusing on the girls. Balthus was in this strange stage in his career: He had had a show that was a flop and was financially forced to take on commissioned portraits of society people. These works are psychologically probing but certainly not flattering; there is almost a meanness to them. It is around this time that he discovered Thérèse, the young girl in his neighborhood, whose youthfulness and honesty was a relief to him. She was kind of moody and not very attractive, but he portrayed an intelligence and strength within her. He named her in the title of the work—the only one of all the children he went on to paint that he ever named. His art then took a new direction and transformed. I wanted to put her into perspective, exploring for the first time why Balthus started these Thérèse images, and where they took him.

Balthus (Balthasar Klossowski) (French, 1908–2001). Thérèse, 1938. Oil on cardboard, mounted on wood; 39 1/2 x 32 in. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Bequest of Mr. and Mrs. Allan D. Emil, in honor of William S. Lieberman, 1987 (1987.125.2)

Nadja Hansen: Was there any one aspect or thread of research that you found particularly illuminating, one that brought new life to the project?

Sabine Rewald: A lot of research went into this. I spent time reading the poet [Rainer Maria] Rilke—an intimate of Balthus who wrote about childhood—reading Balthus's letters recently given to the Bibliothèque Doucet, and trying to track down Thérèse. I have been looking for her for thirty years, personally writing to the city hall of every arrondissement in Paris trying to find birth and death records for her. Finally the 14th arrondissement responded, noting that she was born in 1925 and died in 1950, at the age of twenty-five. I wanted to know what the cause was, thinking it may have been childbirth, so I personally went to the hospital where she died. I told them about the exhibition at the Met and tried to persuade them to give me more information, but they would not release her cause of death since I was not family. Although I continue to extensively search in vain for living relatives, I was still able to find out more than has ever been found before, and maybe someday more will come to light.

Unidentified artist. Daydreaming, 1870s. Location unknown

Balthus (Balthasar Klossowski) (French, 1908–2001). The Blanchard Children, 1937. Oil on canvas; 49 1/4 x 51 1/8 in. Musée du Louvre, Paris, Donation Pablo Picasso (RF1973-56)

Nadja Hansen: You do a wonderful job of drawing comparisons with other artists who similarly took children as their subject, both prototypes and contrasting approaches. Which artists do you think most influenced Balthus, and which, if any, do you think he may have been reacting against?

Sabine Rewald: Like Lewis Carroll, Balthus's works reflect a sense of kinship or intuitive insight into his young sitters. But, unlike Carroll, he is very much interested in the trials—physical and otherwise—of adolescence. His images of children are poignant and sensitive, but with an undercurrent of tension.

There were many nineteenth-century prototypes for paintings of dreamy children, but Balthus completely eliminates the toys and extraneous objects. He greatly admired Courbet and would very likely have seen Courbet's 1844 portrait of his self-possessed sister, Juliette, and you can see how Balthus adopts the same sensuous painterly surface and simplified composition. He just takes it a step further, creating scenes that are entirely uncluttered—with clear, stark, severe interiors—a definite influence of Piero della Francesca, whose work he studied in Arezzo in 1926.

Left: Gustave Courbet (French, 1819-1877). Juliette Courbet, 1844. Oil on canvas; 30 3/4 x 24 3/8 in. Musée du Petit Palais, Paris

Nadja Hansen: You mention in the catalogue that the strict discipline of the composition heightens the erotic mood of the paintings. Can you discuss that further?

Sabine Rewald: Yes, that is where the wonderful tension comes in. Very young girls sit like that—awkwardly, with their legs askew or open, exposing themselves. I see it on the city bus all the time; it is totally unselfconscious. But when Balthus reveals his subjects in what can be deemed erotic positions—in these stark poses and empty rooms, where they often seem moody or brooding—it creates this contrast, this tension. It then becomes about what the viewer brings to it. These children are flaunting themselves seemingly unobserved, but they are observed by the viewer. It is this unselfconscious, natural eroticism that he explores and makes into art.

Balthus (Balthasar Klossowski) (French, 1908–2001). Thérèse Dreaming, 1938. Oil on canvas; 59 x 51 in. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Jacques and Natasha Gelman Collection, 1998 (1999.363.2)

Nadja Hansen: Later in his life, Balthus denied any overt sexuality in his paintings, but critics and viewers have felt very differently. What is your take on his art and his intent?

Sabine Rewald: It's so funny how people get offended or outraged by him; personally, I find his depictions of children delightful. Women just don't write about him because he has been considered so deviant. Perhaps it's because I'm German, but I have never found him offensive. The press talk as if there is something prurient in Balthus's work, but that is totally ridiculous. Even in works like Thérèse Dreaming, the cat may be a tongue-in-cheek stand-in for the artist, but I think it's exactly that—tongue-in-cheek.

Nadja Hansen: The exhibition and catalogue are both called Cats and Girls; why does he so often include cats? What do these cats represent? Are they a stand-in for the male viewer, or does it change from work to work?

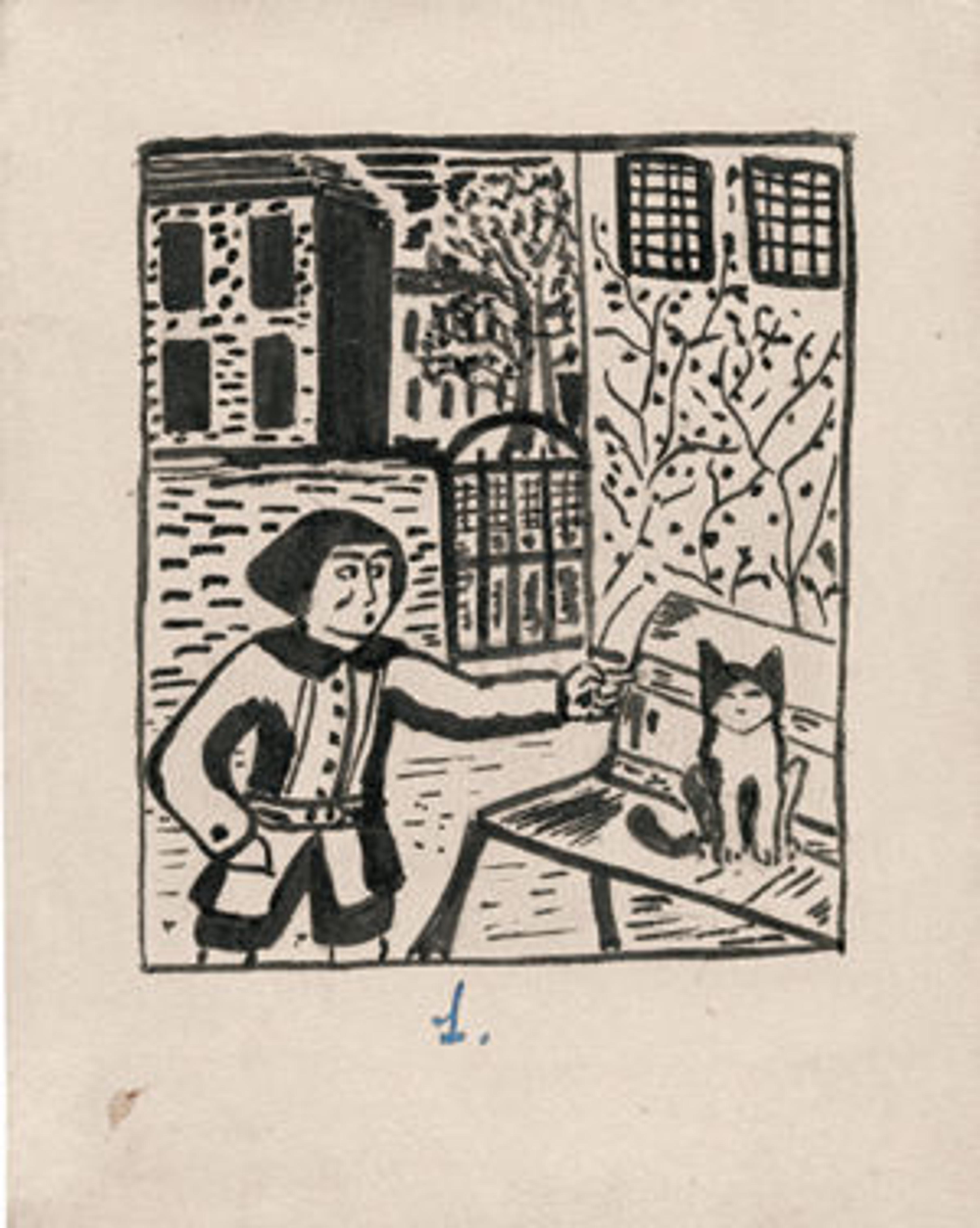

Sabine Rewald: I don't think the cats are symbolic really—I don't see some directly implied sexuality or malignant associations. Balthus loved cats. When he was only eleven years old, he did a much-admired series of ink drawings with an accompanying story all about this cat, Mitsou. So cats are present in his work from the very beginning. Balthus had a house full of cats, and he playfully called himself the King of Cats and his wife the Princess of Cats. Cats are a wonderful foil because they are sensuous animals, but completely unpredictable, aloof, and independent. They don't condescend to play on any other terms but their own. Cats only reach out for you when they want attention, and their affections never last long. In Balthus's later work, which are mostly huge canvasses that I don't care for, the cats disappear and there is a compositional imbalance and dullness to them. I think the cats added a wonderful sense of childish playfulness that was a large piece of the artist's personality.

Above: Balthus (Balthasar Klossowski) (French, 1908–2001). Mitsou, 1919. Series of 40 drawings; ink over graphite on soft, thick, cream-colored paper; first four on slightly darker, stiffer paper; each 6 x 4 3/4 in., with unevenly cut edges. Numbered [not by the artist] 1 to 23 in blue ink and 24 to 40 in black ink. Private collection

Related Link

The Met Store: Balthus: Cats and Girls