Raja Tagore: Renaissance Man of Indian Music

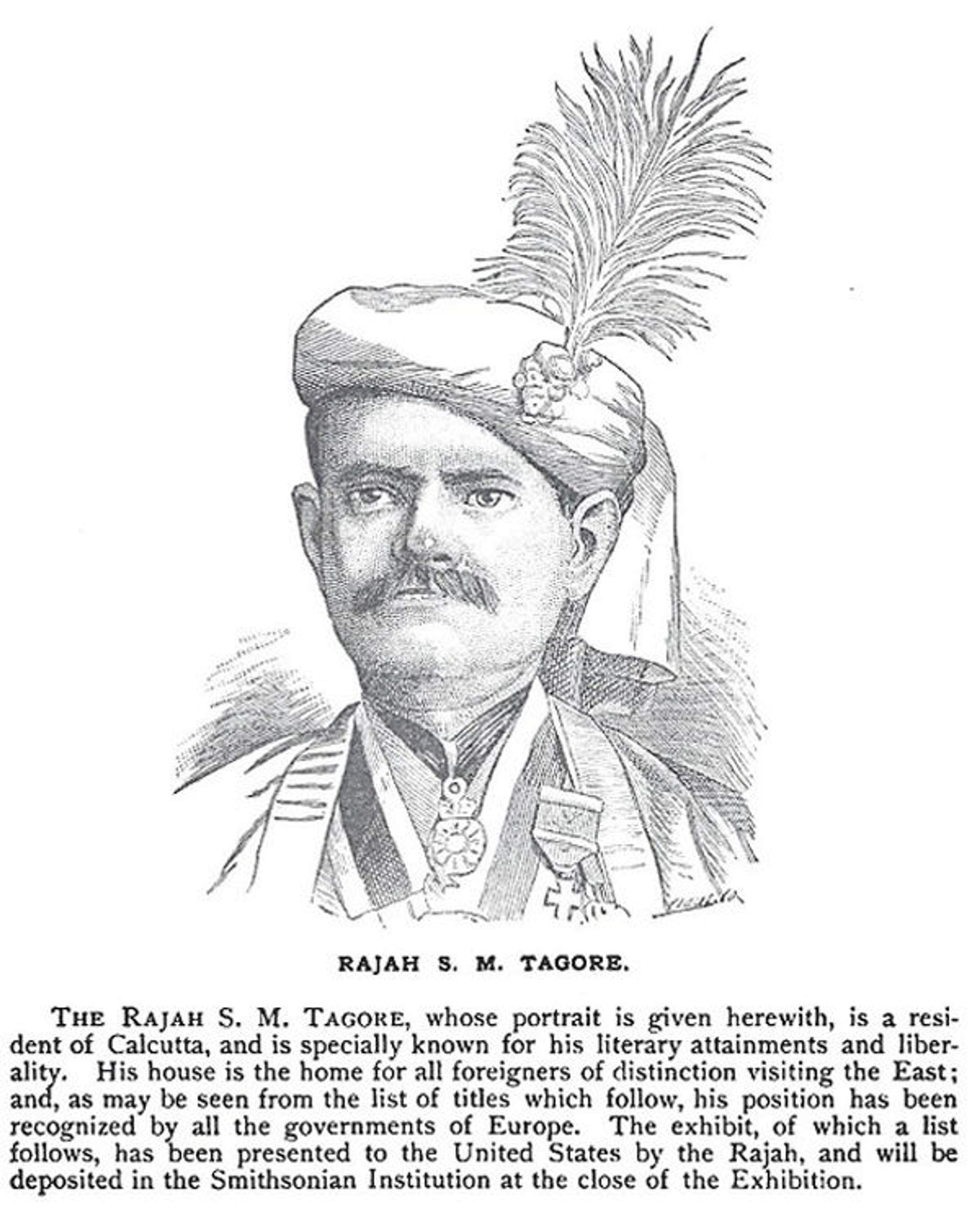

Raja Sir Sourindro Mohun Tagore, from the catalogue of the Boston Exhibition of 1883

«Among the more distinguished benefactors of the Museum's collection of musical instruments was Raja Sir Sourindro Mohun Tagore (1840–1914), a leading figure in the Bengal Renaissance of the late nineteenth century, as well as an educator, patron of music, and musicologist. Tagore was born in 1840 in Calcutta, then the capital of British India, to a Brahmin family—wealthy merchants with lands formerly owned by ruling aristocrats, who were fluent in English and conversant with Western European knowledge. The British often conferred the aristocratic title of Raja on prominent citizens; Tagore's brother inherited the senior title Maharaja, and, in 1880, Tagore himself was titled Raja, though his family had no political authority.»

Tagore attended the European-model Hindu College in Calcutta and developed an interest in music while very young. He published his first book at the age of fifteen, wrote more than forty works on music and musical instruments, developed a notation system for Hindustani music, and later became a leading authority on the theory of what he called "Sanskrit music." A true advocate for music, Tagore was a pioneer in evolving the art form's perception as low-class entertainment and making it a respectable pastime for the elite.

Tagore's European-style orchestra, first established in 1875 when the Prince of Wales visited India. For the orchestra, Tagore used both standard Indian instruments—like the pakhāvaj drum in the center and the tāmbūra on the far right—and instruments modified to incorporate both Western and Indian traditions such as the various sizes of esrāj, comparable to the cello and double bass of Western orchestras.

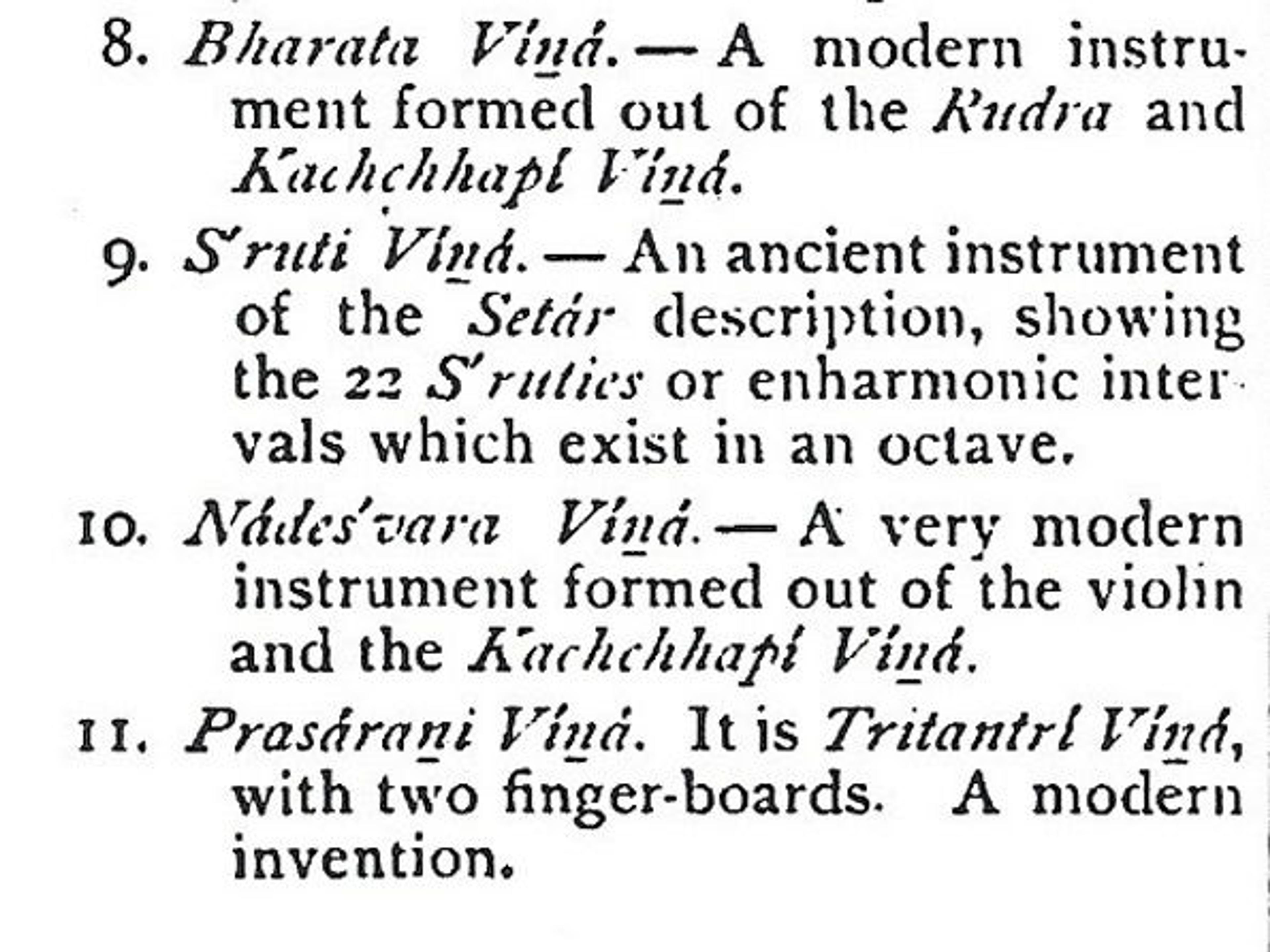

A student of both Western and traditional Indian musical forms, Tagore worked to integrate the two, notably at the Bengal Music School and Bengal Academy of Music, both of which he founded. He formed Calcutta's first "orchestra" (distinct from military bands, which had long existed in British India), and for it developed hybrid Indian/Western instruments which he believed would help to unify and preserve the best of both Indian and Western musical practices. Tagore's output is particularly valuable due of their comprehensive, catalogue-like scope: for example, even in his brief monograph entitled "Short Notices of Hindu Instruments," he identified sixty-five varieties of percussion instruments alone. Today he is best remembered for his tireless work to preserve and expand knowledge of the traditional instruments and musical forms of his native land.

To increase world appreciation of Indian music, Tagore cultivated a wide acquaintance with leading political and cultural institutions all over the world. Though he never left India (owing to a religious belief that overseas travel caused loss of caste), his network included presidents and kings from America, Asia, and Europe; and his work was recognized by honors and decorations throughout the world—from Venezuela, to the Kingdom of Hawaii, to China, the United States, and Persia. He was knighted by Queen Victoria and held honorary doctorates of music from Oxford University and Philadelphia University. Tagore's academic titles were the ones he valued most, and he even successfully petitioned the British government for the allowance to call himself "Doctor."

The Taus, also known as the Mayuri Veena, is one of the more spectacular items in the Tagore collection of musical instruments at the Met. The two names for the instrument come from the Persian and Hindi words for peacock, an auspicious animal often associated with the Saraswati, the Hindu goddess of wisdom, art, and music. Mayuri, 19th century. India. Wood, parchment, metal, feathers. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, The Crosby Brown Collection of Musical Instruments, 1889 (89.4.163)

Tagore's stature and education put him in touch with ruling families and major centers of learning, worldwide. For many of these institutions—including Oxford (where the collection is now at the Pitt Rivers Museum), Brussels, Tokyo, Peking, and the Metropolitan Museum—he assembled collections of instruments and donated sets of his treatises on Indian music and musical instruments. Among the most notable was one sent in 1876 to King Leopold II of Belgium; it formed the nucleus of the Musée Instrumental du Conservatoire Royale de Musique, which immediately became, and remains, one of the world's best museum collections of instruments. Tagore also formed an instrument collection for his own country and donated it to what is now the Indian Museum of Kolkata. Perhaps more important were his comprehensive catalogues, which educated generations of students and scholars, including those at the Met.

Several of Tagore's entries from the 1883 Boston Exhibition catalogue, describing both traditional Indian instruments he had collected and donated, and instruments he had "invented."

Tagore's connections within the United States began in the 1870s. He entertained President Ulysses S. Grant at his Calcutta estate, Emerald Bower, and in 1879 sent a collection of Indian instruments to President Rutherford B. Hayes. In 1883 he was asked to serve as a Commissioner for India for the Foreign Exhibition in Boston. For the Boston Exhibition, Tagore made a collection of fifty musical instruments (as well as 150 books and other objects), which he specifically designated to be sent to the new Smithsonian Institution in Washington, D.C. after the Boston Exhibition closed. The collection was transported from Boston in 1884 by Edwin H. Hawley, whose career at the Smithsonian lasted until his death in 1919. During most of that time he was a prolific correspondent and invaluable source of reference for the Metropolitan Museum's major musical instruments donor, Mary Elizabeth Brown. It may well have been Hawley who put the Brown family in touch with Tagore in 1888.

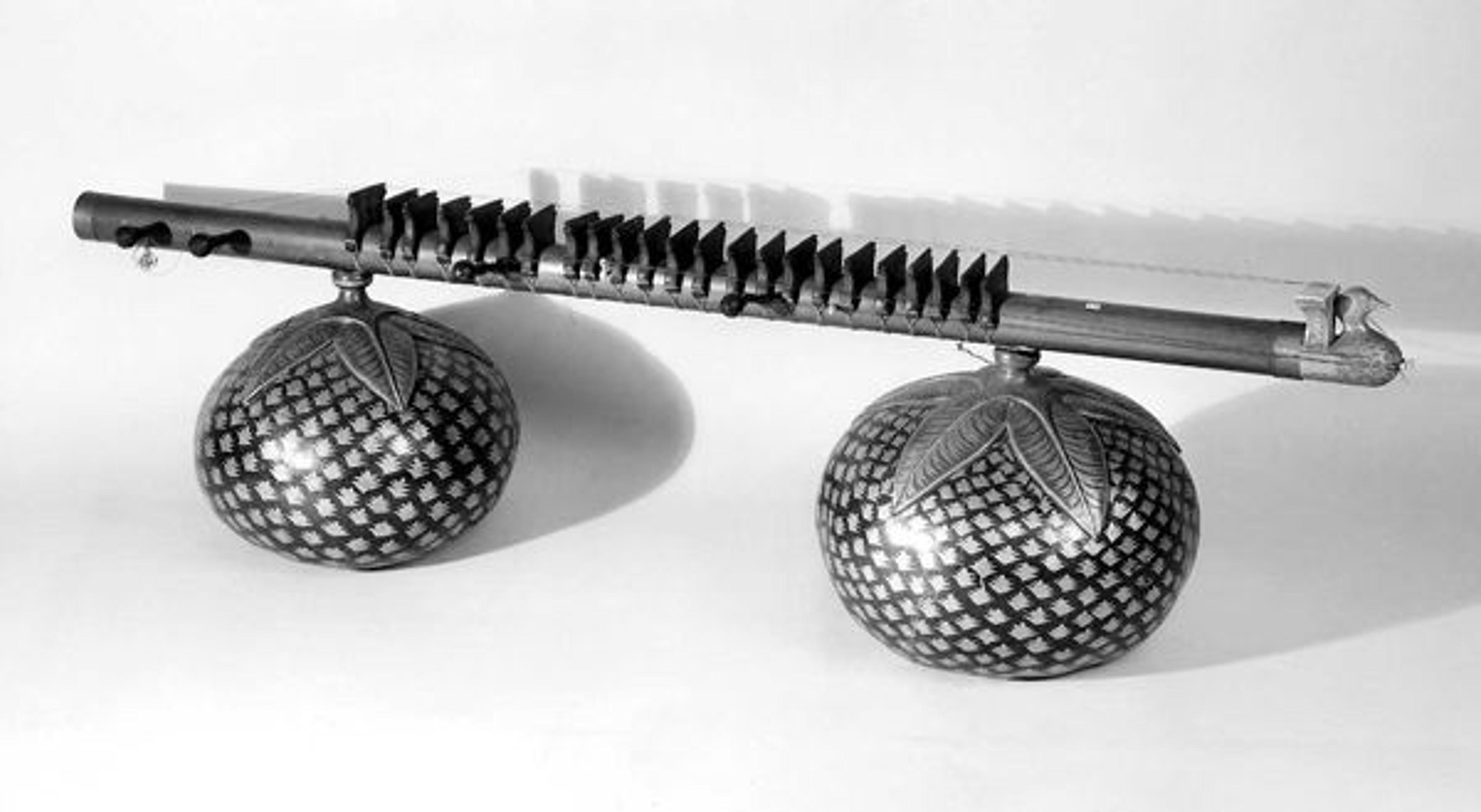

Many of the instruments in the Tagore collection feature the same painted gold-leaf pattern visible on this rudra veena. The rudra veena was the most popular solo stringed instrument of the Dhrupad genre of North Indian classical music. Mahati Vina, ca. 1885. India. Gourd, various materials. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, The Crosby Brown Collection of Musical Instruments, 1889 (89.4.172)

The Brown family, through the family firm, Brown Brothers, and its Indian agent, had contacted Tagore in early 1888 to solicit his assistance in obtaining Indian instruments for their collection. Tagore promised his help and immediately sent copies of his books, although the thirty instruments he donated did not arrive at Brown Brothers until mid-1889—too late to be included in the catalogue, or in the first Brown donation to the Museum. However, William Adams Brown, Mary Elizabeth Brown's son who prepared the 1888 catalogue of the Crosby Brown Collection, acknowledged Tagore in the catalogue and referred to his gift of a "very beautiful and complete collection of Indian instruments." The Museum's annual report for 1889 lists as donations by Mrs. John Crosby Brown two collections of musical instruments: one was her original 278; the other was the Tagore collection, transferred to the Museum in October 1889. The same annual report lists the Tagore books and treatises as donations to the Museum library—important works that were frequently used and cited by curator Frances Morris, especially as she prepared the Museum's first catalogue of Asian musical instruments in 1901.

Tagore died in 1914. His dying wish was that his sitar be cremated with him on his funeral pyre.

Additional Reading

South Asia Journal of South Asian Studies, N.S. Vol. 27, No. 3, Dec. 2004

Katz, Jonathan. "Raja Sir Sourindro Mohun Tagore (1840–1914)." Popular Music, Vol. 7, No. 2, May 1988, 220–221.

Rebecca Lindsey

Rebecca Lindsey is a member of the Visiting Committee of the Departments of Musical Instruments and Islamic Art.

Allen Roda

Allen Roda was formerly a Jane and Morgan Whitney Research Fellow in the Department of Musical Instruments.