Fragments of a panel, 10th century. Egypt. Islamic. Wood; carved with traces of polychrome; 18 1/2 x 27 x 3 in. (47 x 68.6 x 7.6 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Rogers Fund, 1932 (32.102.1,2)

«I am sometimes met with raised eyebrows when I tell friends that part of what I do here at the Met is research the permanent collection of the Department of Islamic Art. After all, the collection is world famous, and in the century since its formation numerous experts have dedicated time and energy to its care. What more is there to research? One of the joys of working with complex artifacts, however, is that there is often more to be discovered, even if the object is well known and has been carefully documented and described in the past. New ways of looking at art emerge as the tools that curators and conservators have at their disposal become increasingly sophisticated, and, because the field of art history itself is always evolving, the questions that specialists ask of objects also change over time.»

Exhibitions often provide the opportunity to ask new questions of old objects. Such is the case with a new research project on a carved wood panel being undertaken in the Departments of Islamic Art and Objects Conservation. The panel, shown above, was carved in a fluid style associated with the ninth and tenth centuries and contains traces of polychrome pigment. It will be included in a show opening this July featuring examples of architectural ornament from early Islamic monuments. As we plan the themes of the exhibition and begin to write the object labels, questions emerge that may not have been answered before.

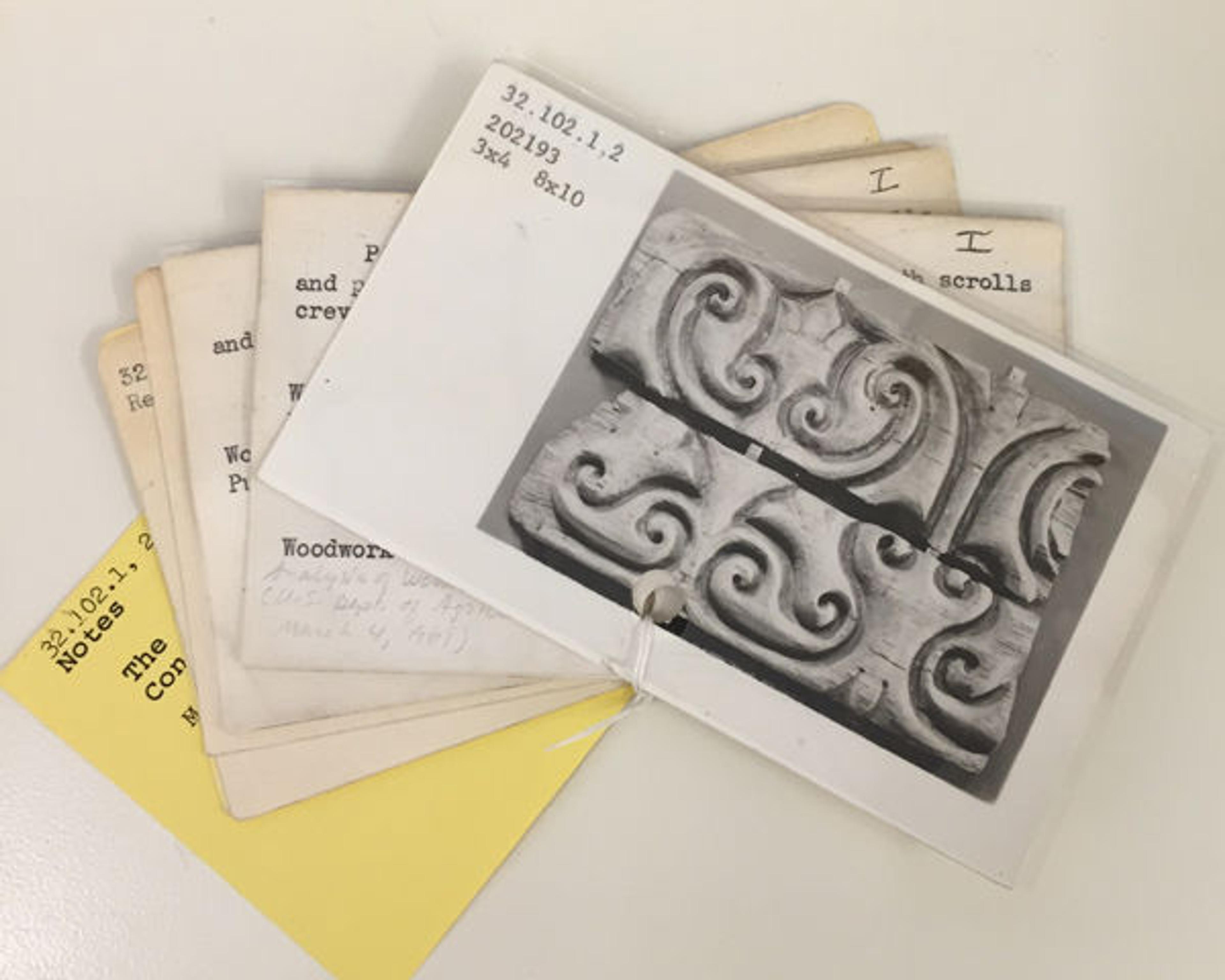

Looking back at the object file for the panel shows the history of questions asked about this particular work. Research on artifacts in museum collections is accumulative, with new findings appended to extant documentation when an object is closely examined for the second, third, and fourth times. In the days when critical information about objects was stored in card catalogs, this process of scholarly accretion was made visible when older index cards were physically attached with string to new cards which noted a change in date, an updated bibliographic reference, or a disputed geographic attribution.

Index cards from the object card catalog with information related to 32.102.1,2

The Museum acquired the panel in 1932, and at that time it was classified as "wood" and dated to "IX – X Century." The first evidence of a new research question came in 1939. At that time the object file stated that Maurice Dimand—a curator who had keen interest in the history of ornament—changed the date to read "tenth century." Dimand likely based this more-precise date on new research being published on the monuments of Cairo. Islamic art history was still a young discipline in the 1930s, as the first major excavations in the field had been published only a decade before. Questions of chronology and stylistic evolution were of great importance to scholars.

The next major appendage to the cards is dated to 1969. It reads: "Analysis by US Dept. of Agriculture, March 4, 1969, Pinus nigra." Thanks to advances in botanical research, the department could now send samples to be precisely identified in a lab. In this case, new tests established that the panel was carved from a species of pine common to the Mediterranean. Similar updates in other object files show that the identification of wood was a larger project that the department undertook at this time. The questions about style asked three decades earlier had been supplemented with new questions about material.

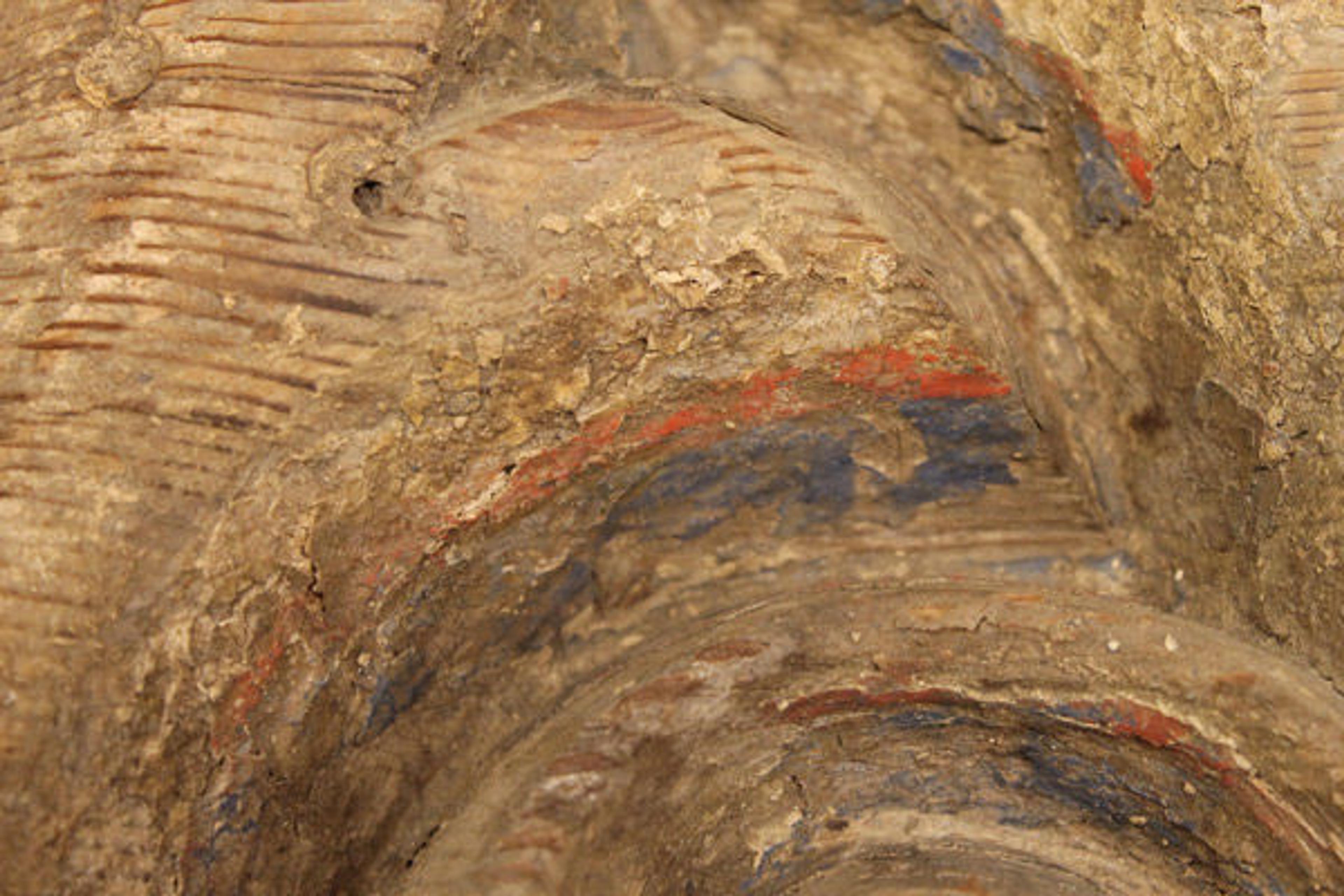

Today the department brings yet another set of questions to the carved wooden panel. We are interested now in the nature of its original polychrome decoration. A large amount of paint is preserved on the surface and the naked eye can already identify white, red, and blue layers—so what did the piece originally look like, and to what extent did it change over time? The second question asks how the piece would have been used in its original context: was it part of a ceiling or a wall, and where in a building might it have been placed? Such questions are indicative of larger trends in art-historical research in recent years, as efforts to reconstruct the original look of historical monuments has become more advanced thanks to the development of digital tools.

Detail of 32.102.1,2, which shows traces of blue and red paint clinging to the surface

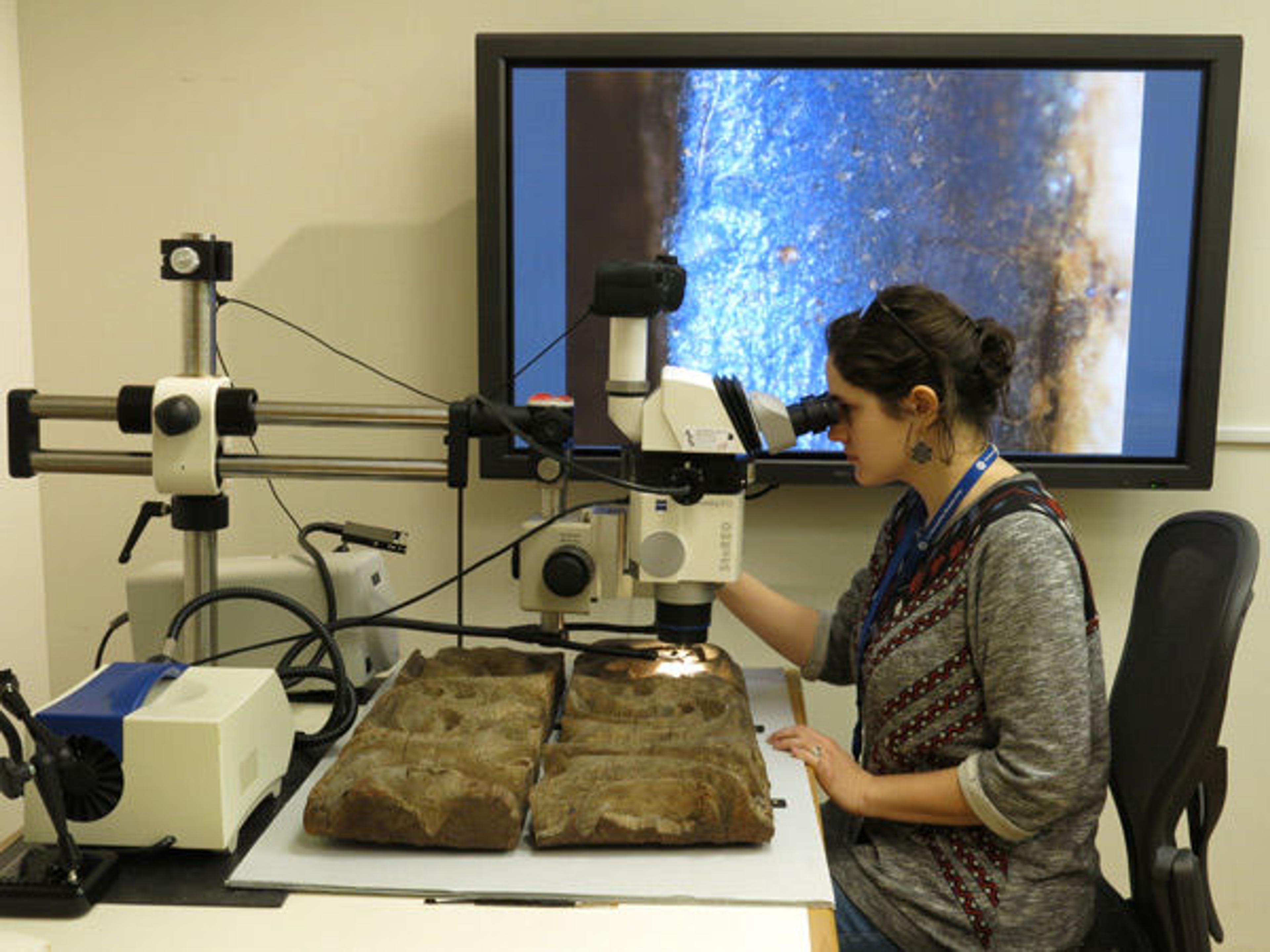

Curatorial departments might initiate research projects by raising relevant questions, but answering these questions is often a collaborative effort between museum departments. The questions about the polychrome decoration and original function of this panel, for example, are better tackled with the expertise of conservators. Mecka Baumeister, a conservator at the Met with a specialization in wood, and Gaëlle Gantier, a conservation intern, are currently both looking closely at the object to tackle some of these questions. To establish the nature of the piece's polychrome ornament, Mecka and Gaëlle are examining the piece using different microscopes: one with a camera attached to capture details, and another that displays magnified images on a screen.

Conservation Intern Gaëlle Gantier examines wooden panel 32.102.1,2 under a stereo microscope. The image on the screen behind her shows the blue paint under high magnification—the projected live-view of the camera attached to the microscope.

To establish possible functions of the piece, Mecka and Gaëlle have also taken X-rays that make it possible to see the joinery in greater detail. In a second phase of the project, the two will take samples of the polychrome decoration to establish, together with colleagues in the Department of Scientific Research, what materials were used to create it. Some interesting conclusions about the use of the piece over time are already emerging from this investigation. Namely, it appears that the visible red and blue paint was applied to the surface after the object had been removed from its original context. This indicates that the piece may have been restored in antiquity and therefore had more than one "life" as a piece of architectural decoration.

As information emerges from research undertaken in the conservation lab, new questions are sent back to the Department of Islamic Art: Are there pieces in other collections with comparative traces of pigment? Are there examples of monuments where a similarly carved piece is preserved in situ? This collaborative brainstorming is part of the process of updating information on works of art in the Museum's collection.

After completing their analysis, Mecka and Gaëlle will be writing a follow-up to this post that will outline some of their findings in greater detail. For now, I will conclude by posing one last question to readers: Twenty years from now, after our project is concluded and another curator or conservator returns to this same piece for a new exhibition or catalogue essay, what questions will they ask of it?

Related Link

Blog posts related to the Department of Objects Conservation