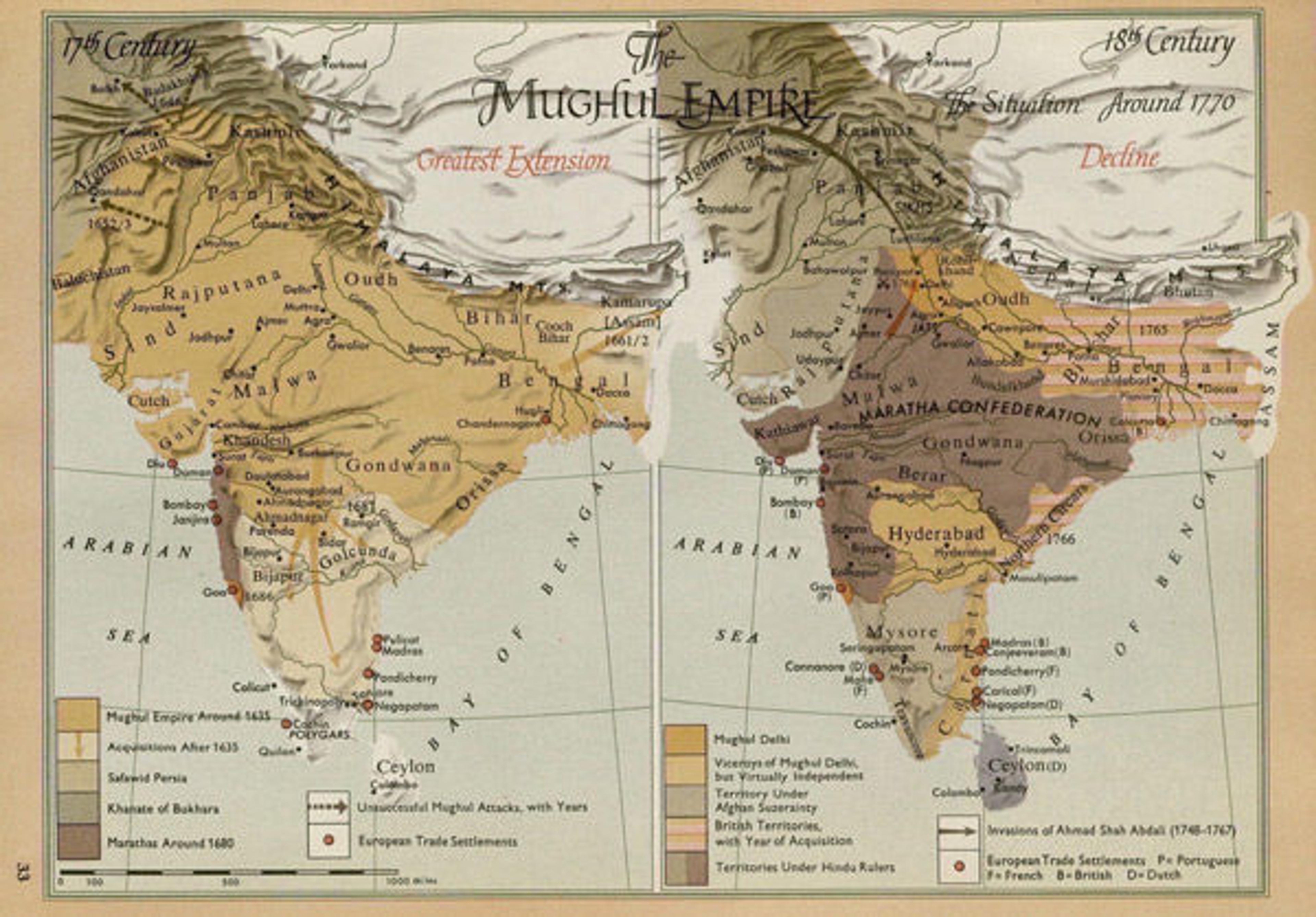

Roelof Roolvink, Historical Atlas of the Muslim Peoples (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1957), 33.

«In the permanent collection of the Department of Islamic Art are two miniature paintings from Avadh (Oudh), India. Avadh, located in the northeastern province of Uttar Pradesh, was once ruled by the Nawabs of Avadh (1722–1856), a group that gained autonomy during the disintegration of the Mughal Empire. Quickly, the Nawabs and their courtiers had to contend with the rise of the East India Company. After a decisive victory in the Battle of Buxar in 1764, the East India Company used Avadh as an effective buffer state against encroaching powers such as the Marathas and the Rohillas.»

The art of Avadh underscores this complicated, connected history, with Avadhi miniature painting in particular characterized as eclectic, weaving a hybrid of Persianate, Mughal, Indic, and European visual vocabularies. A testament to the interregional dialogue occurring in South Asia at the time, Avadhi miniatures drew from a variety of painting techniques and were overall invested in the depiction of "light and shadows and a more accurate rendition of volume and space" (Losty, 2011). Mihr Chand, Nidha Mal, Mir Kalan Khan, and Muhammad Faqirullah Khan are the most cited and celebrated artists who worked in and around Avadh. Many of them migrated to cities within Avadh, such as Faizabad and Lucknow, after the ruler of Persia, Nadir Shah, sacked Delhi and devastated the Mughal army in 1739. At this juncture, there was an enmeshed network of artistic patronage spurred by courtly elites and also by European traders. Indeed, foreigners like Richard Johnson, Jean-Baptiste-Joseph Gentil, and Colonel Antoine-Louis Henri Polier collected and even commissioned complete painting albums.

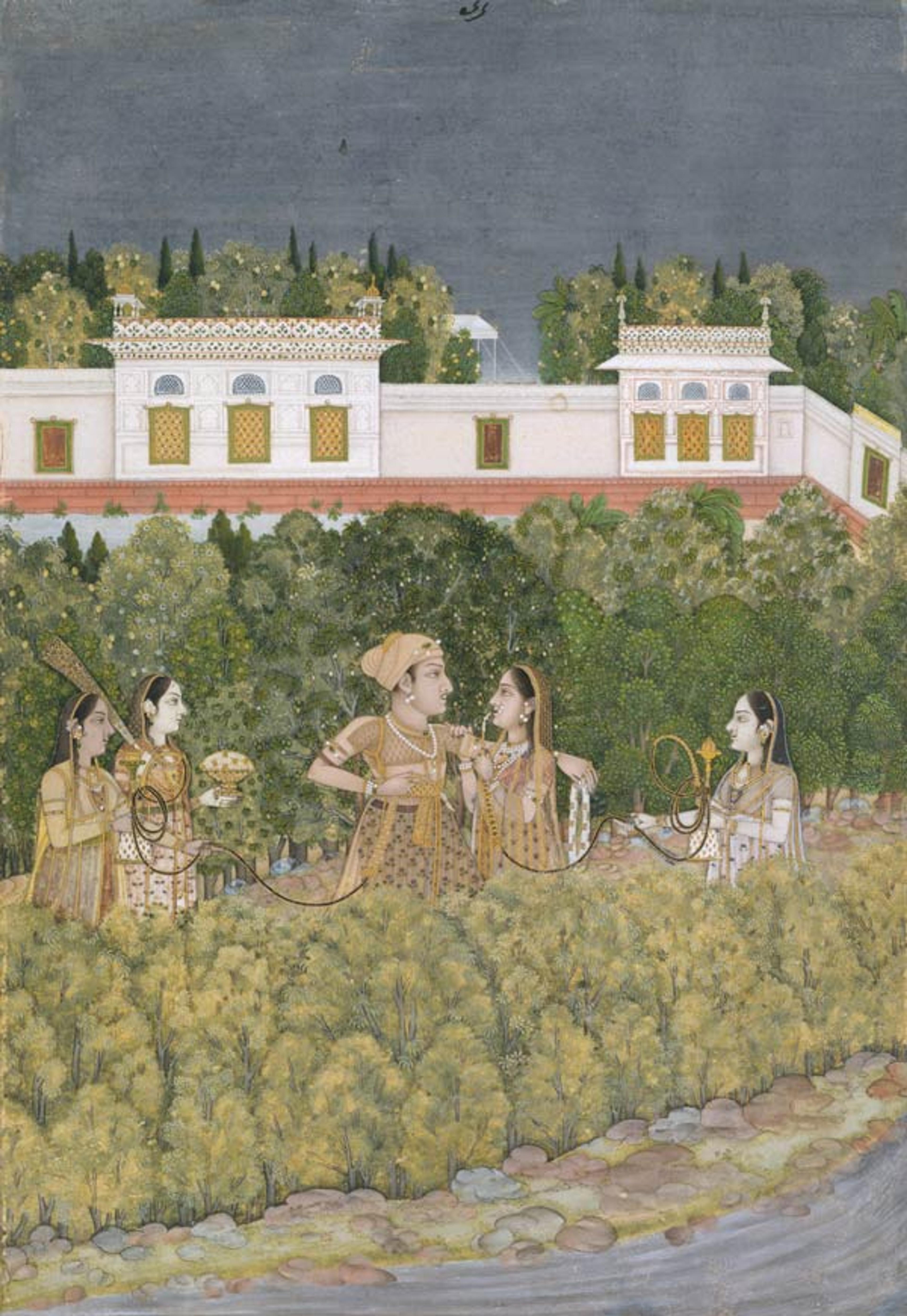

Nidha Mal. Prince and Ladies in a Garden, mid-18th century. Lucknow, India. Islamic. Ink, opaque watercolor, and gold on paper; 10 5/8 x 7 3/8 in. (27 x 18.7 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Cynthia Hazen Polsky and Leon B. Polsky Fund, 2001 (2001.302)

Prince and Ladies in a Garden features a couple flanked by their female servants. Thematically, the painting touches upon the union (waṣl) of beloved (ma'shūq) and lover (āshiq). In a South Asian aesthetic philosophy, rasa—which translates to taste, essence, or sentiment—is an overarching feeling that arises within the viewer. In this case, the scene exudes the sringara rasa, the amorous essence, and yet, the artist, Nidha Mal, envelops this scene of desire in a sober compositional structure. Overall, Nidha Mal's paintings are reminiscent of the late Mughal artist Chitarman's aesthetic, their styles matching in their usage of cool whites and frieze-like compositions.

Furthermore, Nidha Mal used a variety of spatial conventions for his terrace scenes. Here, the white wall on the right recedes toward the viewer. As a result of this perspectival device, the viewer is aware that the couple stands in an enclosed garden space bordered by an architectural surrounding and not in an open arena of wilderness, where the couple would have been more exposed. In lyrical and visual representations, trysts commonly occurred in gardens, spaces that accommodated court sociability and forms of decorum. Thus even within the pictorial imaginative space of Prince and Ladies in a Garden, seduction is represented along the ethical and courtly convention of a garden.

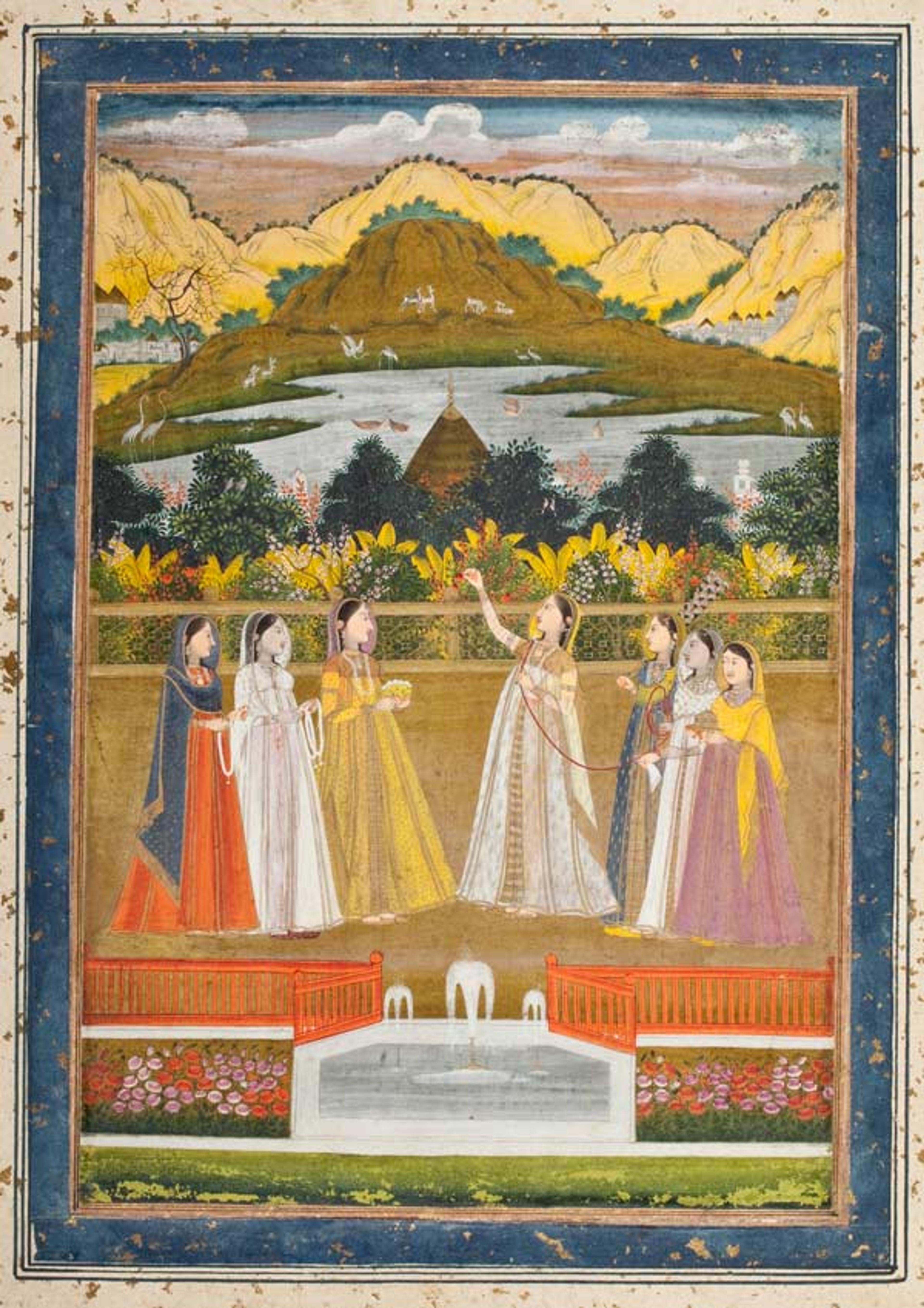

Princesses Gather at a Fountain, 1770. Farrukhabad, India. Islamic. Opaque watercolor and gold on paper; 9 x 13 5/8 in. (22.9 x 34.6 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Cynthia Hazen Polsky and Leon B. Polsky Fund, 2001 (2001.421)

Princesses Gather at a Fountain was produced in Farrukhabad, in the province of Avadh, where the painting tradition primarily employed a yellowish green color for landscapes. In this work, the rolling hillside bears this trademark chartreuse coloring. Because of Farrukhabad's close proximity to the Nawabs of Avadh—80 miles from Lucknow and 160 miles from Faizabad—artists frequently traveled between the courts. Many Farrukhabad paintings adopt the palette and technique of the Lucknow artist Muhammad Faqirullah Khan, who depicted female figures with elongated lower torsos, sharp noses, and oval faces. Princesses Gather at a Fountain invokes this trademark style. On closer inspection, the elongation of the female body was perhaps an extension of Persian poetics. In many Persian poems found on, behind, or alongside Avadhi miniature painting, women's bodies are compared to a slender cypress tree (sarv); indeed, the many female bodies that punctuate this painting are very cypress-like.

Sringara rasa is also present in Princesses Gather at a Fountain. For instance, the two women in the lower right-hand corner and the cluster of women to the right of the fountain are in an embrace, emphasizing the amorous sentiment of this piece. Additionally in the background are pairs of cranes, rabbits, and antelope, which are understood as a poetic metaphor of the lovers longing to be reunited. Similarly, a Farrukhabad painting in the collection of the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, A Princess and Her Companions Enjoying a Terrace Ambiance, contains the same motif of pairing animals in order to celebrate an amorous union either between the women or with an impending beloved.

Attributed to Muhammad Faqirullah Khan (Indian, active circa 1720–1770). A Princess and Her Companions Enjoying a Terrace Ambiance, circa 1760–1770. India, Uttar Pradesh, Farrukhabad. Opaque watercolor and gold on paper; Image: 11 x 7 1/2 in. (27.94 x 19.05 cm); Sheet: 16 1/8 x 11 3/4 in. (40.96 x 29.85 cm); Mat: 27 3/4 x 21 3/4 in. (70.49 x 55.25 cm). Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Los Angeles, Art Museum Council Fund (M.2005.159)

Moreover, in Princesses Gather at a Fountain, the scale of the animals is slightly disproportionate. For instance, near the left of the lake is a pair of birds with their wings in expansion, which appear quite larger than the buildings to the left of the lake. Since the birds and building lie on the same horizontal plane, the birds should have been smaller than the buildings in order for the painting to adhere to the protocols of perspective. Yet the emphasis here is not on naturalism but on the intensification of visual motifs that index the overall mood of the painting. The fountain, for instance, is pushed forward onto the picture plane, allowing the viewer to see all dimensions of the fountain at once. For a more natural rendition, the sides of the fountain would have fallen in a diagonal and thus only part of the water within the fountain would have been visible. By bending the rules of perspective, the artist (or artists, since multiple hands were usually involved in one painting) accentuated the whole layout of the fountain. In addition, water is repeatedly referenced in visual arts and literature as conduits of paradise. To extend this line of reasoning to the Princesses Gather at a Fountain, the artist/artists dramatized this aquatic trope of the fountain to suggest both a paradisiacal and pleasureful abode occurring within the painting.

Resources

Alam, Muzaffar. The Crisis of Empire in Mughal North India Awadh and Punjab, 1707–48. Delhi: Oxford University Press, 1986.

Ali, Daud. Courtly Culture and Political Life in Early Medieval India. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004.

Falk, Toby, and Mildred Archer. Indian Miniatures in the India Office Library. London: Sotheby Parke Bernet, 1981.

Gude, Tushara Bindu. "Hybrid Visions: the Cultural Landscape of Awadh." In India's Fabled City: The Art of Courtly Lucknow, edited by Stephen Markel, Tushara Bindu Gude, and Muzaffar Alam, 69–102. Los Angeles: Los Angeles County Museum of Art, 2010.

Leach, Linda York. Mughal and Other Indian Paintings from the Chester Beatty Library, Volume II. London: Scorpion Cavendish, 1995.

Losty, Jeremiah P. "Indian Painting from 1730 to 1825." In Masters of Indian Painting, Volume II, edited by Milo Cleveland Beach, Eberhard Fischer, B. N. Goswamy, and Jorrit Britschgi, 111–118. Zurich: Artibus Asiae Publishers, 2011.

McInerney, Terence. "Mughal Painting during the Reign of Muhammad Shah." In After the Great Mughals: Painting in Delhi and the Regional Courts in the 18th and 19th Centuries, edited by Barbara Schmitz, 12–33. Mumbai: Marg Publications on behalf of the National Centre for the Performing Arts, 2002.

Okada, Amina, ed. Power and Desire: Indian Miniatures from the San Diego Museum of Art Edwin Binney 3rd Collection. San Diego: San Diego Museum of Art, 2002.

Roy, Malini. "The Revival of the Mughal Painting Tradition during the Reign of Muhammad Shah." In Princes and Painters in Mughal Delhi, 1707–1857, edited by William Dalrymple and Yuthika Sharma, 17–24. New York: Asia Society Museum, 2012.

Related Link

RumiNations: "Games of Scale in a Golconda Painting" (May 26, 2015)