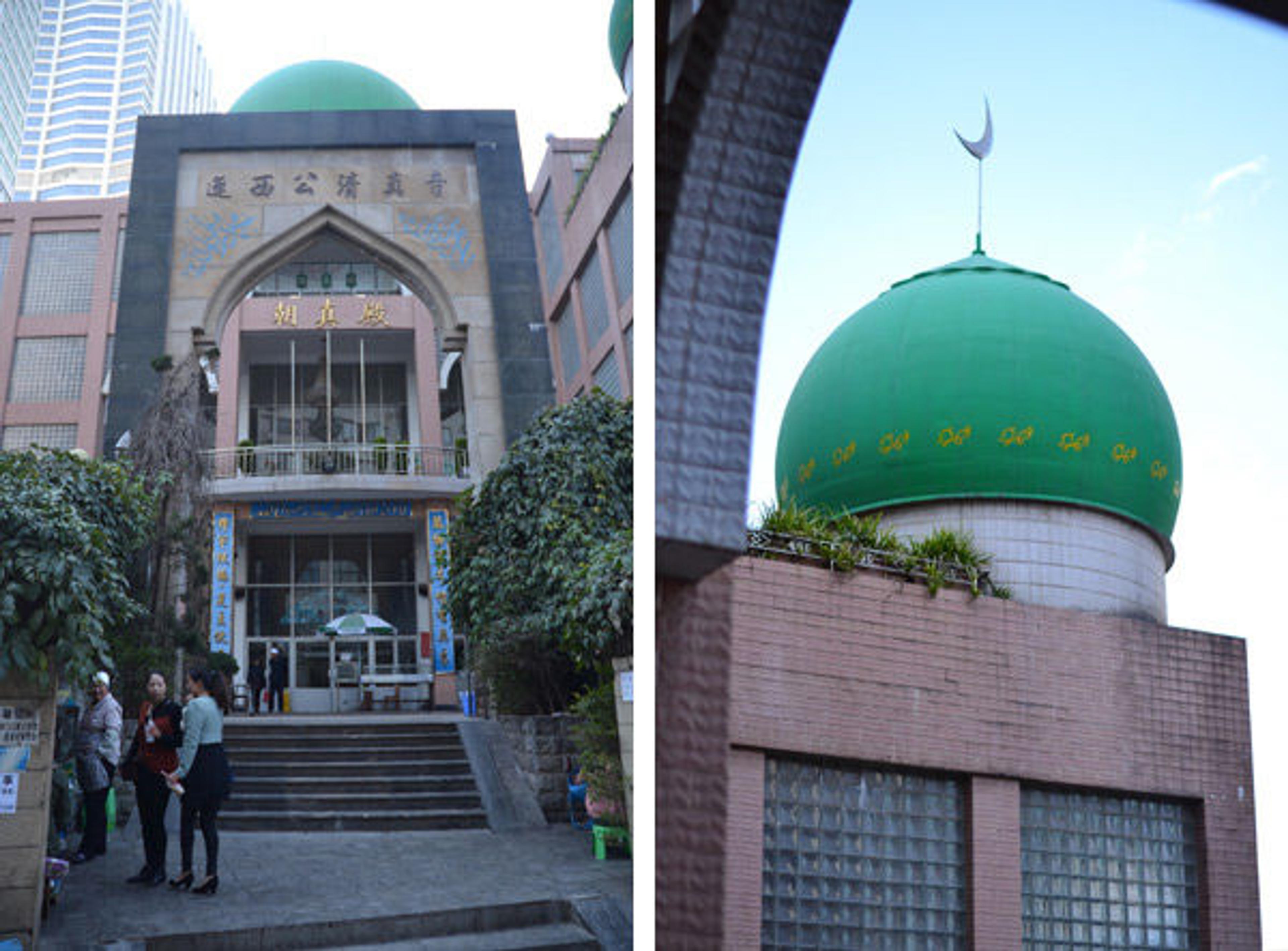

Yixigong Mosque, in Kunming, Yunnan Province, China. Photos courtesy of the author

«My time as a volunteer in the Department of Islamic Art here at the Met has allowed me to reflect on my experience studying abroad last year in China and gain new perspective on the relationship between cultures that I had not previously considered. While in China, I had the opportunity to visit Kunming, the capital city of the southern Yunnan province. Dubbed the "eternal spring city," most days in Kunming consisted of cloudless blue skies and a light breeze, perfect conditions for exploring the city. While walking around the center of Kunming, I happened to see, among the sea of concrete and glass buildings, a bright-green dome topped with a steel crescent moon. Intrigued, I wove my way through alleyways until I came to the green-domed building. Much to my surprise, the structure was a mosque, bustling with people leaving midday prayer.»

Although much of China's historical narrative leads Westerners to believe the country is almost entirely secular and that much of the culture is homogeneous, this is certainly not the case. To find a mosque in the center of a large Chinese city is actually a common thing, and illustrates the fact that China is actually an amalgamation of many different cultures. Specifically, China and Islam have a rich history of artistic influence that can be traced back to the ancient trade routes of the Silk Road. Since that time, Chinese and Islamic cultures have been open to a flow of ideas, artistic inspiration, and people.

While walking through the Galleries for the Art of the Arab Lands, Turkey, Iran, Central Asia, and Later South Asia at the Met, I saw evidence of the exchanges between China and Islam in many forms of art—from pottery and decorative arts to paintings. The connections between Chinese and Islamic art can be seen in the direct imitation that appeared during and after the Ilkhanid (Mongol) period (1206–1368), as well as in the fundamental similarities that formed long before the two cultures were brought closer together.

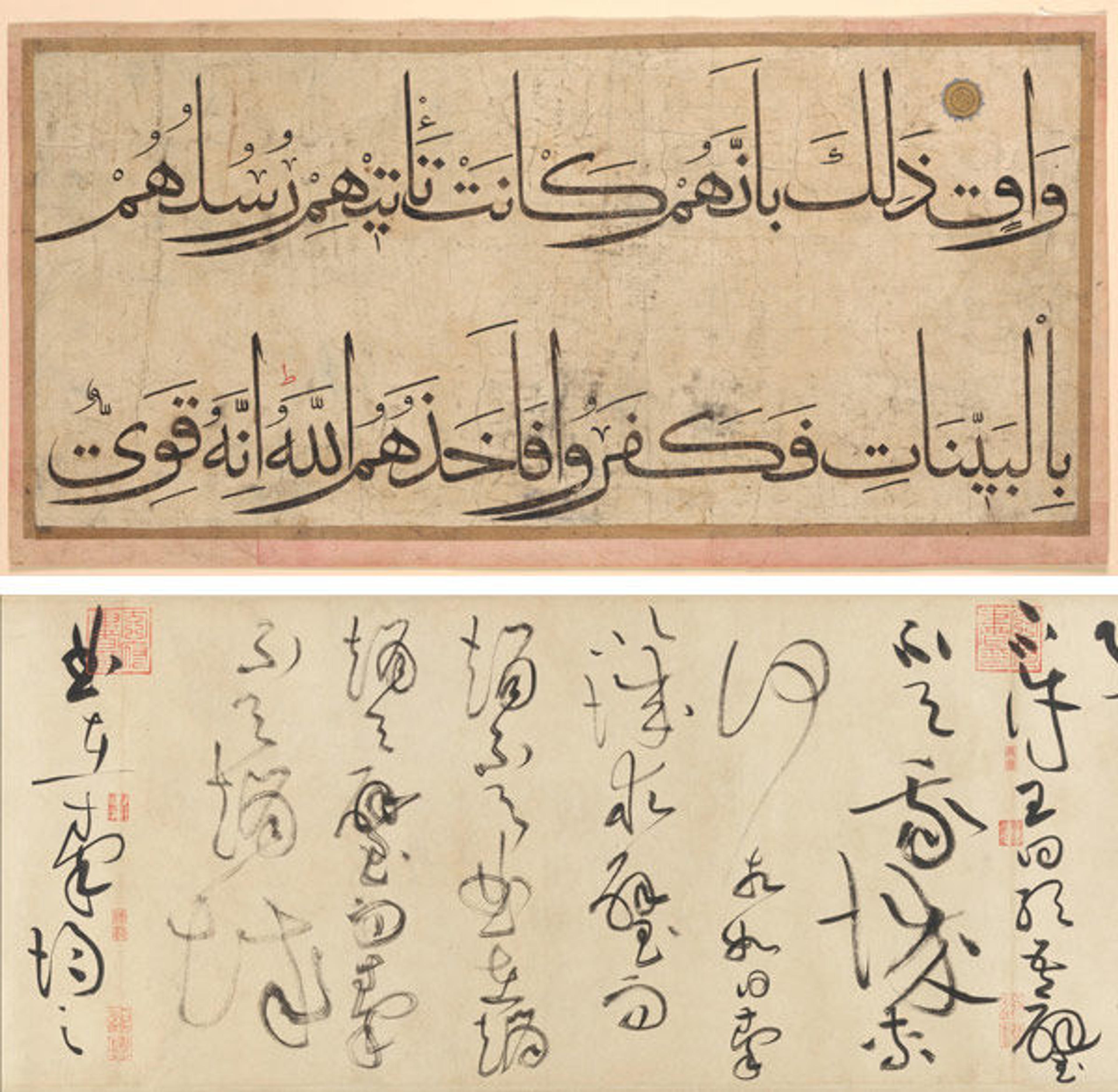

Calligraphy is the most highly regarded form of communication in both cultures. In Islamic art, Arabic calligraphy was intrinsically tied to the Qur'an, which sanctified calligraphy and the tools used to create calligraphic artwork. Similarly, the writing of Chinese calligraphy is a spiritual process in which the artist must be in tune with nature and their own body in order to create balanced and cohesive characters.

Top: Copied by 'Umar Aqta.' Section of a Qur'an manuscript, late 14th–early 15th century. Present-day Uzbekistan, probably Samarqand. Islamic. Ink, opaque watercolor, and gold on paper. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Anonymous Gift, 1972 (1972.279). Bottom: Huang Tingjian (Chinese, 1045–1105). Biographies of Lian Po and Lin Xiangru, ca. 1095. China. Handscroll; ink on paper. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Bequest of John M. Crawford Jr., 1988 (1989.363.4)

While Chinese is a pictographic language and Arabic is an alphabetical script, there are noticeable visual similarities in the weight and rhythm of the written languages. Although the two cultures grew apart over time, this fundamental likeness in artwork foreshadows the more explicit transference of ideas and iconography.

The connections between Chinese and Islamic art originated with works of pottery. Beginning in the ninth century, Chinese wares made their way to the Islamic lands, where they served as a great inspiration for local potters and craftsmen. Yet the artistic relationship between these two cultures is not as simple as China solely influencing Islamic art; rather, there was a symbiotic relationship created in which techniques, motifs, iconography, and form influenced and inspired both cultures.

This relationship can be seen most explicitly in the renowned blue and white porcelains, especially in the thirteenth century. Since the Mongolian empire, which spanned from central Europe to the eastern shores of Japan, brought the Islamic lands and China under the same dominion, these two regions were able to trade artistic goods in a direct and free manner. While it is known that the Chinese porcelains were widely coveted and inspired the creation of many different imitations, including Dutch delftware, it is less known that that these wares were first developed for the Near Eastern market, and that many of the design aspects were inspired by Islamic metalwork. The use of repetitive banded decorations and the division of the surface into multiple panels can be seen to have had a direct aesthetic influence on Chinese blue and white porcelain.

The transference of the use of banding and creation of friezes can be seen in this comparison of an eleventh-century Islamic ewer and a later sixteenth-century Chinese vase. Left: Ewer with inscriptions and hunting scenes, 11th century. Iran, Nishapur. Bronze; cast, engraved. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Rogers Fund, 1938 (38.40.240). Right: Bottle with Daoist immortals, late 16th–17th century. Ming Dynasty (1368–1644), Wanli period (1573–1620). China. Porcelain painted with cobalt blue under transparent glaze (Jingdezhen ware). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Rogers Fund, 1916 (16.61)

During and after the Mongol period, blue and white porcelains dominated the Chinese export market. Many of these works found their way to the Islamic lands, where potters were once again inspired by the exceptional quality of these Chinese objects and began to create their own interpretations. Examples of blue and white porcelain from both China and Islamic lands can be seen side by side in the Islamic Art galleries.

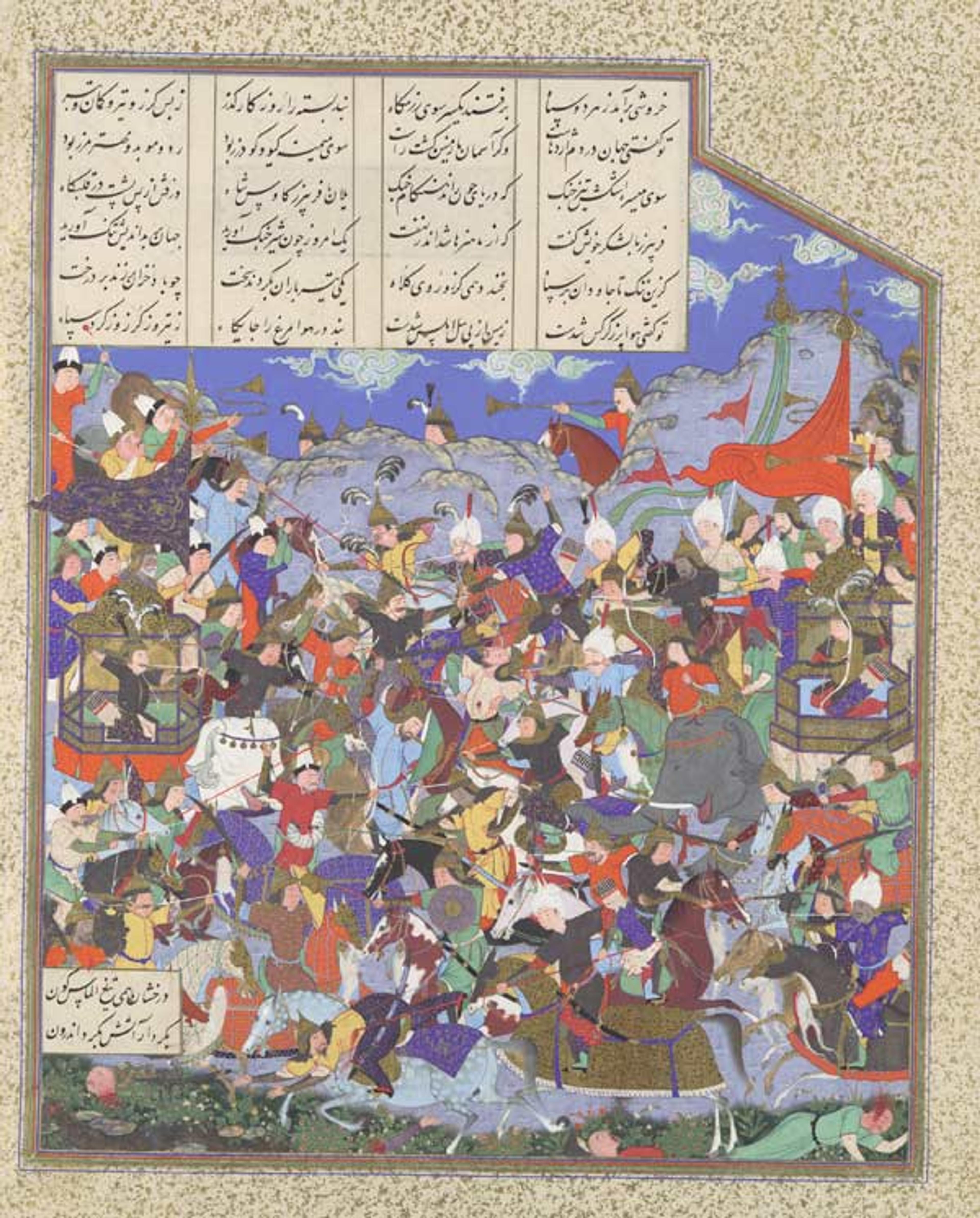

Three-dimensional pottery and decorative arts were not the only media affected by the artistic exchange between China and Islam, however. Starting with the Mongol conquest, Chinese motifs and imagery found their way into two-dimensional Islamic paintings as well. For example, some the folios from the famous Shahnama (Book of Kings) of Shah Tahmasp contain highly stylized, knotted white clouds—a motif commonly found in Chinese blue and white porcelains. While Chinese clouds had already made their way into Persian painting by the fifteenth century, artists continued to include these forms for years to come, a testament to the high regard with which the Chinese arts were held within the Islamic lands.

"The Battle of Pashan Begins," Folio 243v from the Shahnama (Book of Kings) of Shah Tahmasp, ca. 1530–35. Iran, Tabriz. Opaque watercolor, ink, silver, and gold on paper. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Arthur A. Houghton Jr., 1970 (1970.301.37)

Another common motif that originated from China and was used in Islamic artwork is the phoenix, referred to as fenghuang in Mandarin. Commonly depicted as a soaring creature with long, trailing plumage, the fenghuang is symbolic of femininity in Chinese culture yet does not necessarily hold the same connotation and cultural meaning when used in Islamic contexts. The Metropolitan Museum's tile with image of phoenix, a late thirteenth-century Iranian section of a frieze on display in gallery 455, is a fantastic example of Chinese imagery and iconography translated into Islamic artwork. While not technically a two-dimensional object, the piece is representative of the imagery often found in Persian paintings, which include the phoenix, stylized clouds, and flowers.

Tile with image of phoenix, late 13th century. Iran, probably Takht-i-Sulaiman. Islamic. Stonepaste; modeled, underglaze painted in blue and turquoise, luster-painted on opaque white ground. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Rogers Fund, 1912 (12.49.4)

Even though museums are usually divided into departments based on culture or geographic region for organizational purposes, I believe that one of the greatest parts of the museum experience is seeing the artistic impact when two or more cultures interact and share ideas. The intermingling of peoples from seemingly disparate cultures is certainly one of the most important aspects of human history, and seeing this process take place through the visual arts is fascinating. Just as I witnessed at the Yixigong Mosque, different cultures exist alongside and within each other in ways that may be surprising. The link between China and Islam is not the only connection to be seen, and I encourage all patrons of the Met, or any museum, to look for these networks and discover that any two cultures are much more connected than previously imagined.

Resources

Gray, Basil. "Chinese Influence in Persian Painting: 14th and 15th Centuries." In The Westward Influence of the Chinese Arts from the Fourteenth to the Eighteenth Century, Percival David Foundation Colloquies on Art and Archaeology in Asia 3 (1972a): 11–17.

Medley, Margret. "Chinese Ceramics and Islamic Design." In The Westward Influence of the Chinese Arts from the Fourteenth to the Eighteenth Century, Percival David Foundation Colloquies on Art and Archaeology in Asia 3 (1972a): 1–10.

Watson, Oliver. "Chinese-Iranian Relations, XI: Mutual Influence of Chinese and Persian Ceramics." Encyclopædia Iranica (online edition, 2015), accessed May 20, 2015, http://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/chinese-iranian-xi.

Watson, Oliver. "Islamic Pots in Chinese Style." In The Burlington Magazine 129, no. 1010 (1987): 304–6.