Shiva Ahmadi (American, born Tehran, Iran, 1975). Pipes, 2013. Islamic. Watercolor, ink, and acrylic on Aquaboard; Framed: H. 40 3/4 in. (103.5 cm), W. 60 7/8 in. (154.6 cm), D. 2 1/2 in. (6.4 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, 2012 NoRuz at the Met Benefit, 2014 (2014.525)

«Even though most paintings become richer when viewed up close, the work of Shiva Ahmadi expands greatly with close looking, revealing itself in ways I couldn't have anticipated, even after examining the highest-quality digital image files. I first experienced Ahmadi's work in person at a 2014 Asia Society exhibition, Shiva Ahmadi: In Focus. I remember being transfixed by the piece on view: Lotus, an animation made from a 2013 watercolor triptych. It was incredible to see her meticulously painted figures come alive in their environment. Beyond their visual allure, Ahmadi also imbues her compositions with so much narrative content, that to see this narrative actually expand over time—animated through movement—deepened the work's meaning immensely for me. My only wish at the time was to get even closer.»

I recently got my wish when I had the opportunity to examine one of the Met's own pieces in the Department of Islamic Art, Pipes. Since the Museum acquired the piece in 2014, it has yet to be exhibited in the galleries. However, the work will be on view from January 12 through April 2, 2016, at New York University's Grey Art Gallery, where it will be part of the exhibition Global/Local 1960–2015: Six Artists from Iran.

Before Pipes left the Met and traveled downtown, I visited our storeroom to view the painting with Associate Curator Maryam Ekhtiar. At any distance, the content of Ahmadi's work stands out—from the easily identifiable objects (pipes, bombs, and arrows) to the more ambiguous figures that benefit from some knowledge of Indian and Persian literature and painting. Up close, though, it is her facility with materials that captivates me. It's powerful to see a watercolor at this scale (just over five feet wide), especially when considered against the department's collection of miniature paintings, which are stylistically similar but obviously smaller.

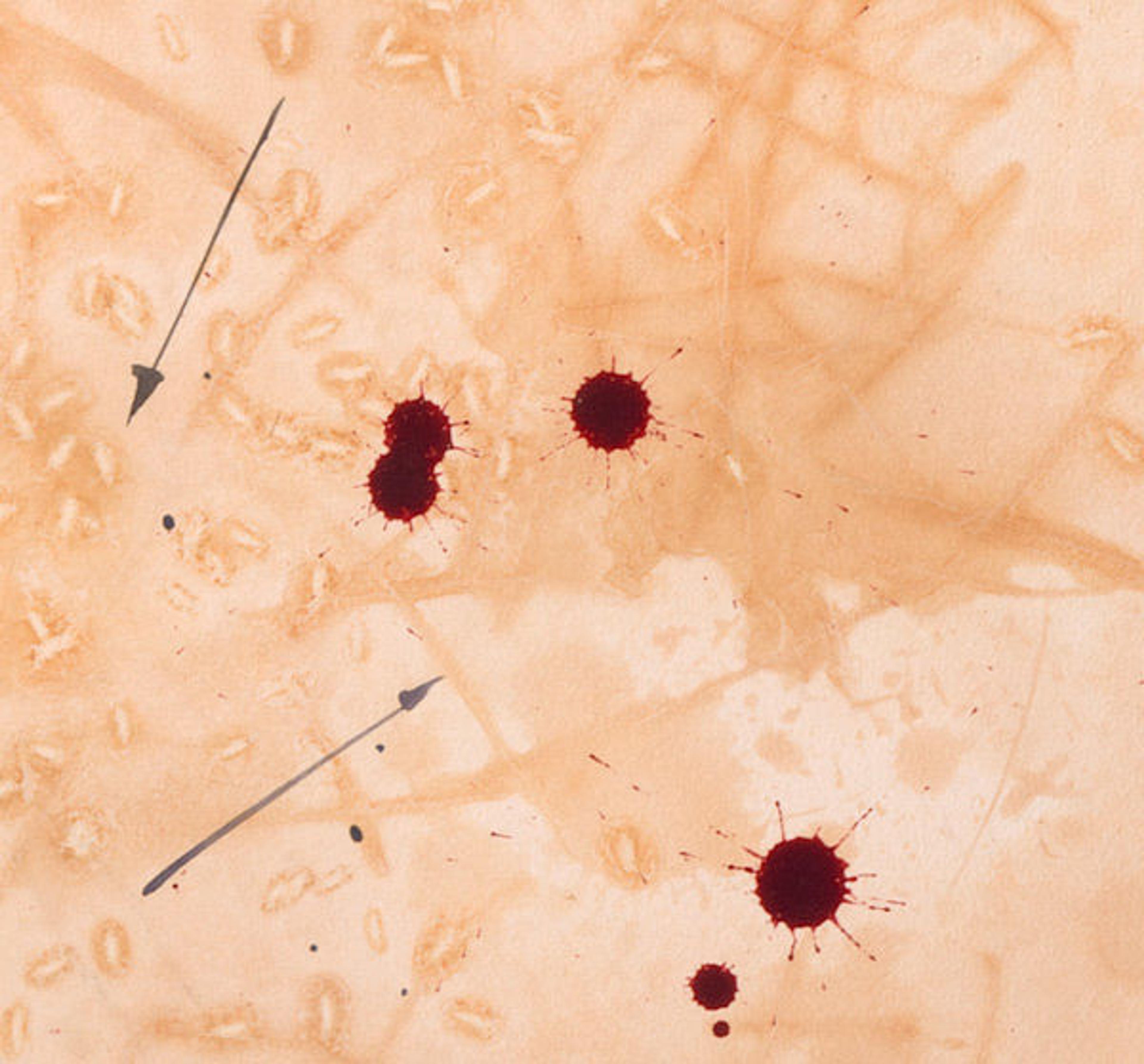

Painted on Aquaboard, a stiff support more absorbent than paper, the colors are deep and sometimes dark, but always maintain their luminosity. It feels as though they have bled into the surface with some combination of control and spontaneity. Red splotches are equally suggestive of paint and blood. Depending on your distance from the work—taking in the entire scene, or viewing only a fragment—both interpretations are satisfying. Ahmadi masterfully strikes this balance between material abstraction and clear figuration.

Detail view of Pipes showing the deep richness of the work's red splotches

The background of Pipes is easy to miss from afar, especially since the figures dominate. After stepping closer, I noticed that it was not composed solely of a monochrome beige, but rather a chaotic field of light specks and strands against darker splotches. I later watched an interview with Ahmadi in which she described her unconventional process for achieving this abnormal pattern: hair, rice, and salt granules strewn on the page, which together create variegated tones as the watercolor dries. Like the uncontrollable quality of watercolor, this technique touched me in its willing loss of control.

Detail view of Pipes highlighting the use of hair, rice, and salt granules to add texture to the painting's surface

This scattered effect resonates with Ahmadi's subject matter: the chaos wrought by war; the disorder as regimes turn corrupt; the unpredictable effects of unbridled power. These themes have deep meaning for Ahmadi, who was born in Tehran in 1975 and experienced the Iran–Iraq War firsthand. When she moved to the United States to pursue graduate degrees in painting and drawing, this content did not immediately surface. Additionally, having been surrounded by reproductions of Persian miniature painting in Iran, she was not particularly interested in the tradition at that time either. It was only when she arrived in the U.S. that she returned to her roots and began working these ideas into her painting.

This content has only become stronger over the past decade. Despite her clear references to modern-day conflicts across the globe, what's most powerful to me is that her work avoids becoming too literal. The meaning of each work is left open to interpretation as each viewer wanders through Ahmadi's materially seductive field, gently reminding us of the value and beauty of slowing down and getting close.

Related Link

RumiNations: "The Shahnama in Contemporary Iranian Art" (October 27, 2015)