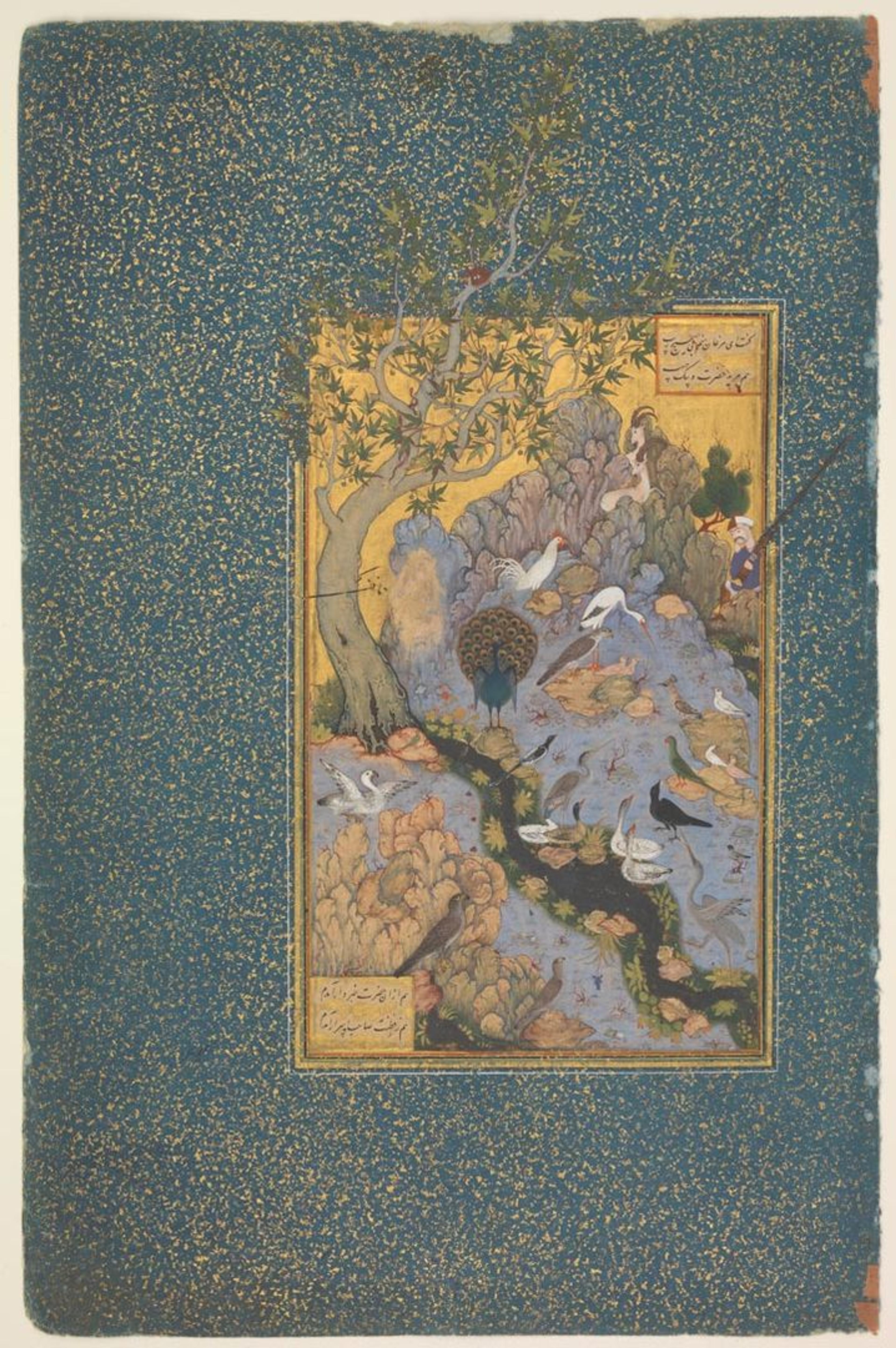

Painting by Habiballah of Sava (active ca. 1590–1610). "The Concourse of the Birds," Folio 11r from a Mantiq al-Tair (Language of the Birds), ca. 1600. Iran, Isfahan. Islamic. Ink, opaque watercolor, gold, and silver on paper; Painting: H. 10 in. (25.4 cm), W. 4 1/2in. (11.4cm); Page: H. 13 in. (33 cm), W. 8 3/16 in. (20.8 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Fletcher Fund, 1963 (63.210.11)

«The Concourse of the Birds, a 12th-century poem by the Persian poet Farid ud-Din 'Attar (ca. 1142–1220), has become a beloved text in both religious and secular contexts. The poem speaks of a wise hoopoe who leads all the birds on an expedition to find the Simurgh, a legendary creature whom they would like to crown their leader. An allegory of the Sufi's journey to self-realization and union with God, the words, lines, and stanzas of this poem conjure magical scenes. Brilliant birds fly through cavernous valleys while overcoming various limits and distractions, all of which serve as metaphors for the various difficulties in achieving the most profound of mystical practices: full unity with God. Their numbers diminish until only 30 birds—si (30) murgh (birds) in Persian—reach the fabled Simurgh, who, as it turns out, is simply their own reflection.»

I love that The Concourse of the Birds is an adventure story embedded in a poem with religious overtones. As enchanting scenes unfold one after another, I never imagined that these moments could be translated to the realm of visual arts. A magnificent illustrated manuscript of The Concourse of the Birds in the collection of The Met's Department of Islamic Art, however, proved me wrong.

Initially commissioned by Sultan Husayn Mirza Bayqara in 15th-century Afghanistan, the manuscript was later passed down to Shah Abbas I (r. 1588–1629), who added various illustrations before donating it to a prestigious shrine of the Safavid ruling family in Ardabil, Iran. Illustrated with paintings in both the Timurid and Safavid styles—two of the most refined, beautiful, and highly praised periods of Persian painting—each miniature brings tangible images of seemingly inexpressible ideas to the page.

Detail from The Concourse of the Birds

In my time as a college intern here at The Met, I had not expected to find an illustrated manuscript of the Mantiq al-Tair, nor did I even know any existed. All I knew was that I had read the text and loved it. So when I discovered this work, my attention jumped gleefully from detail to detail: the hidden faces in the rock formations, the falcon's piercing stare, the rooster's playful position near the center of the page, the hunter's surprised expression. (The last one, in hindsight, I likely mirrored, as it seemed that neither of us expected to come across such an enchanting scene that day.) At some point, my eyes rested on the peacock—the soft feathers on his chest, his angelic wings, the eyes of his magnificent tail.

The image pulled me back from the page as I remembered what the peacock often represents in Sufi literature: earthly attachments and, in the case of the poem, a fallen soul. This was truly perplexing to me. If an important goal to all Sufi writers is transcendence of all ties that bind one to the mundane, how ought one receive and perceive an artwork as beautiful as this folio?

Another object in The Met collection that explores similar themes is a stunning 19th-century Persian mirror case depicting a rose and a nightingale.

Painting by Zain al-'Abidin. Mirror case, A.H. 1206 / A.D. 1844–45. Iran. Islamic. Exterior: pasteboard, papier-maché, opaque watercolor, gilded and lacquered; Interior: mirror; H. 9 1/4 in. (23.5 cm), W. 5 5/16 in. (13.5 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Catherine and Robert Harper, in memory of Drs. Grigor and Arax Acopian, 2009 (2009.170)

In The Concourse of the Birds, the nightingale is the first bird to refuse to partake in the difficult journey to find the Simurgh. As the leader of the birds, the hoopoe responds that the nightingale has only "superficial love . . . [for] only for the outward show of things," as demonstrated by his attraction to the rose, a common trope in Sufi literature. The beauty of the mirror case above, in conjunction with the theme of its decoration, fits the vanity of checking one's own reflection. The roses, so finely painted, almost jump out of the lacquer, and for a second one might even imagine their sweet scent moving slowly through the air.

Ultimately there is no single answer to how one should respond to the visual richness of the manuscript; viewers can react to beauty in a number of ways. While the manuscript's contemporary setting in The Met's galleries praises beauty for the aesthetic pleasure it provides, it might have been perceived quite differently in its previous courtly or religious settings.

Moreover, there is a reason why so many Sufi poets have tried to express the inexplicable quality of mystical ecstasy. It is an experience that can only be understood through deep spiritual practice and study. In this type of enlightened state, beauty is not necessarily attached to the mundane. Rather, it is a celebration of God beyond the sensual joy we feel in the presence of beautiful objects. While anyone might claim this sophistication and wisdom, only few truly understand it. Thankfully, though, we all can appreciate this folio in one way or another, even if it is only the gold that catches our eye.

Related Link

RumiNations: Alexandra S. McKeever and Kate Justement, "Intern Insights: A Summer of Study and Exploration" (August 11, 2015)