Plastic, Paint, and Movie Magic: A Close Look at Disney Animation Cels

The animated films of Disney are some of the best known worldwide. The movie magic that integrates story, movement, and sound was created from a marriage of artistic creativity and technological development. One of the important components of the animation process is the thousands of individual images that when photographed and shown rapidly in sequence created the illusion of movement. The Metropolitan Museum of Art owns several of the animation cels and drawings that were a fundamental part of the film making process. A close look at these reveals a side to movie magic that often goes unseen.

Production and sheets

For the production of animated films, the static components such as the background were created on paper or board and the moving figures and objects were drawn onto clear material to produce an animation cel that would be photographed in front of the backgrounds (fig. 1).

Figure 1. Walt Disney Enterprises. The Evil Witch with Vultures, ca. 1937. Gouache on two layers of celluloid over watercolor and gouache background, Sheet: 10 in. x 9 in. (25.5 x 22.8 cm). Gift of Bella C. Landauer (Ref.LaundauerDisney.2)

For decades these films required 24 hand-drawn and colored images per second of screen time meaning each feature-length film required the production of hundreds of thousands of animation cels. This industry was enabled by the advances in plastics technology that could produce clear, thin, flexible films. The earliest motion picture film, released in approximately 1889, was made from a polymer called cellulose nitrate also known as celluloid. Celluloid is a semi-synthetic plastic made from the combination of cellulose, a natural material found in plants, nitrogen-based chemical compounds, and other additives processed to form sheets. This was the same material used for making early animation cels as it was thin and flexible. One of the additives belongs to a class of chemicals called plasticizers which helped make the plastic films flexible. However, over time the plasticizers can evaporate, and the cellulose nitrates molecules recrystallize causing them to distort and become more brittle with the result being animation cels that are rippled and wavy (fig. 2).

Figure 2. Walt Disney Enterprises. The Evil Queen, ca. 1937. Gouache on celluloid, Sheet: 12 1/4 x 9 7/8 in. (31 x 25 cm). Gift of Bella C. Landauer (50.511.12)

Painting the sheets

Figure 3. Photomicrograph of figure 8. Walt Disney Enterprises. Snow White (detail), ca. 1937. Gouache on celluloid with cut and pasted celluloid and paper applied to a watercolor on paper background, Sight: 6 7/8 x 9 3/8 in. (17.5 x 23.8 cm) Gift of Bella C. Landauer (Ref.LandauerDisney.3)

Figure 4 a, b. On the left the front and on the right the back of the celluloid sheet. Walt Disney Enterprises. Snow White (detail), ca. 1937. Gouache on celluloid, Sheet: 12 1/4 x 9 7/8 in. (31 x 25 cm). Gift of Bella C. Landauer (50.511.13)

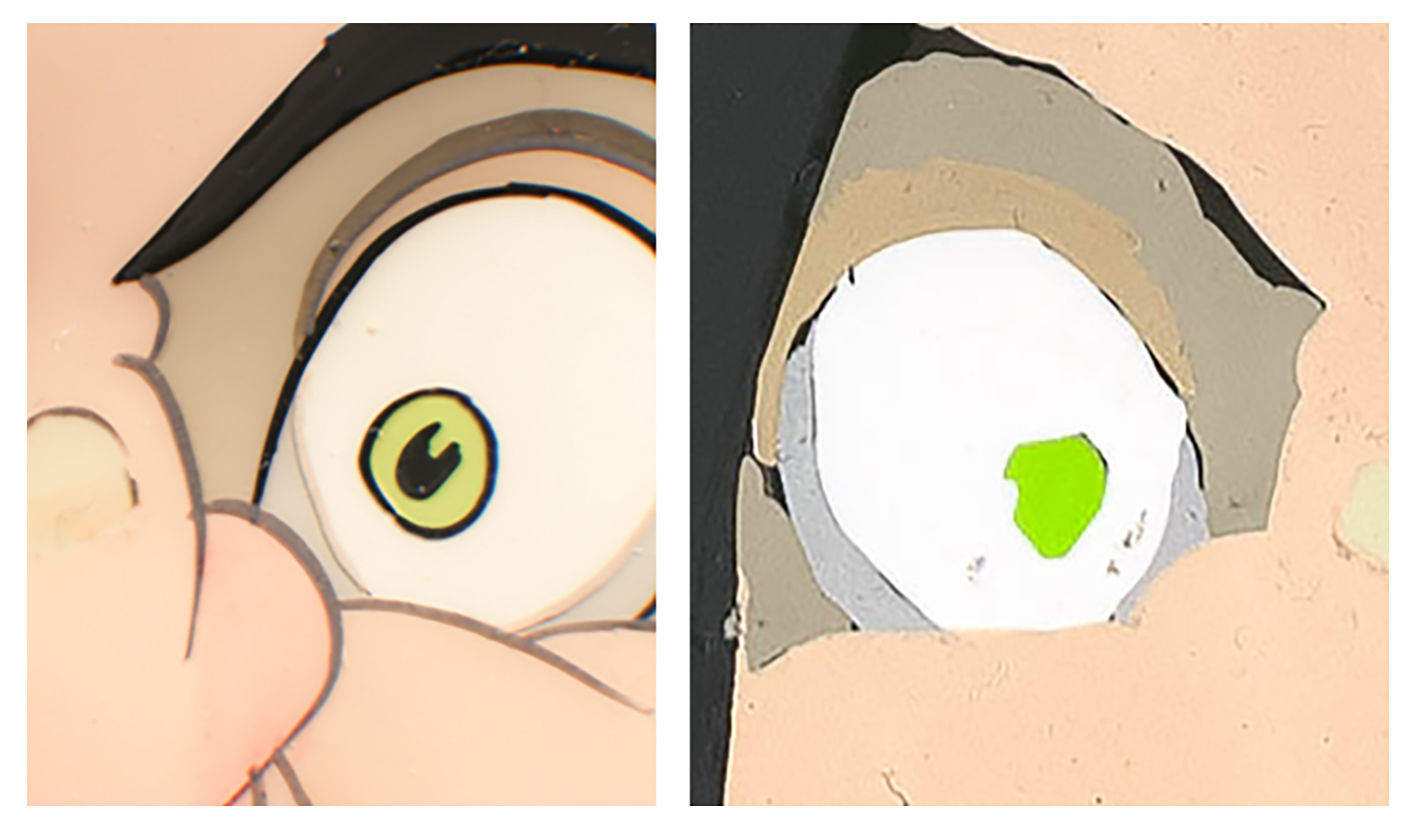

After numerous sketches were worked out, the designs, outlines, and certain details of the figures were on painted on cellulose nitrate sheets. This process was called inking the sheets and was done with a thin brush in black, gray, and white, with red for details such as lips (fig. 3). The celluloid sheets were then turned over and painted with bright water-based paints that were thick, smooth, and designed to flow across the cellulose nitrate support creating vivid fields of color with no visible brushstrokes. Some of The Met’s Disney cels remain as individual sheets, allowing access to the backside revealing some of the painting techniques. The side the cels were painted on is not the viewing side, requiring painters to understand the flow of the paints and layering of the colors. A detail of the cel of the head of Snow White (fig. 4a) shows how the fine details such as the lips, eyes, lashes, and hair stay clear and distinct on the front, while the reverse (fig. 4b) shows how the broad fields of color were applied. Details of the front and back of one of the eyes of Evil Witch from the film Snow White (fig. 5) emphasizes how the variety of colors and intricate arrangement of tone and shadow seen on the front was achieved by purposeful and ordered application of thick layers of color on the back. The knowledge and skill of the cel painter was required to achieve this thousands of times. Both of these examples (figs. 4 and 5) show how the paint on the verso appears blobby but is smooth, even lay and flawless from the front.

Figure 5 a, b. On the left the front and on the right the back of the celluloid sheet. Walt Disney Enterprises. The Evil Witch (detail), 1937. Gouache on celluloid, Sheet: 9 7/8 x 12 1/4 in. (25 x 30.9 cm). Gift of Bella C. Landauer (50.511.10)

Later presentations

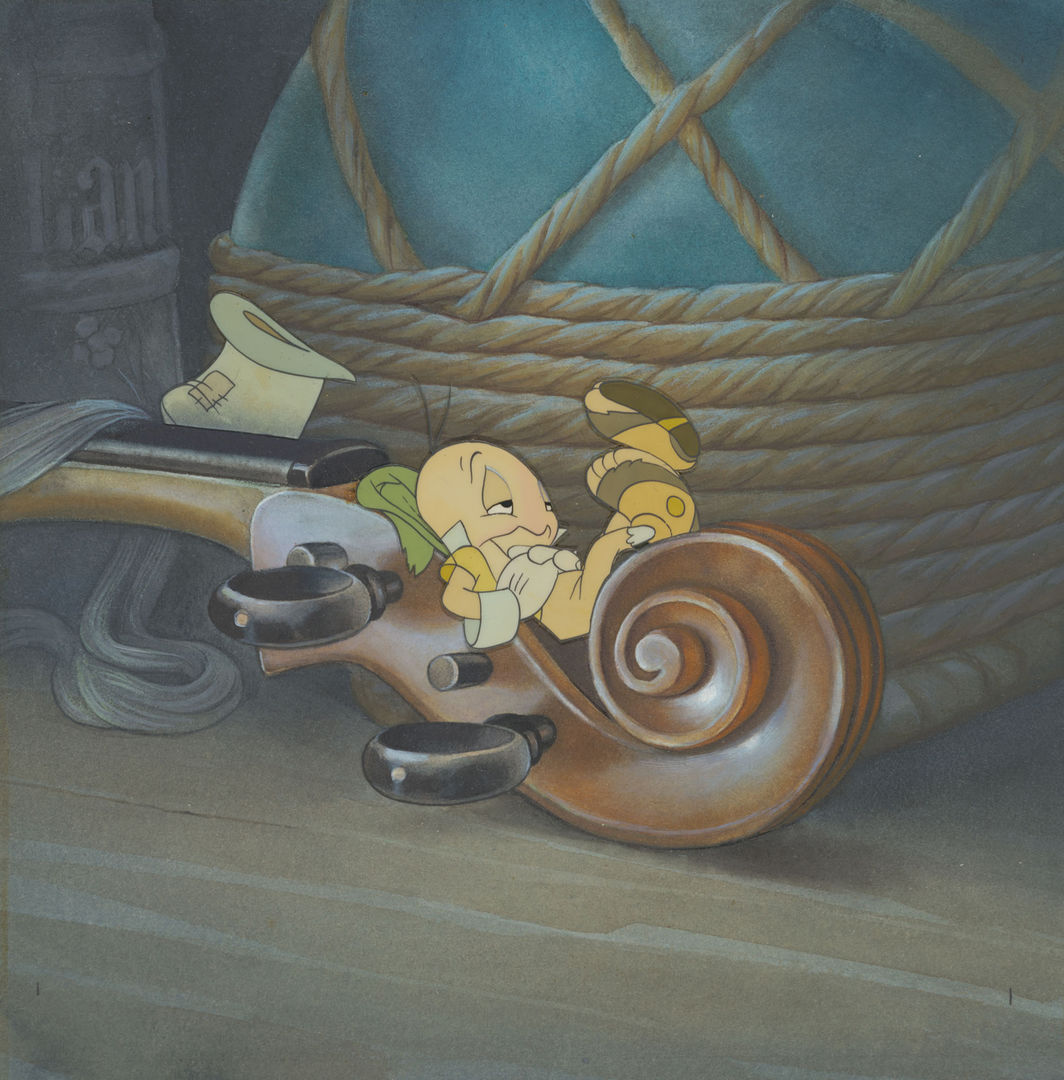

As there were many thousand sheets produced by the animation artists, beginning in the late 1930s, The Walt Disney Company in collaboration with Courvoisier Galleries prepared and sold the animation cels as works of art ready for hanging. Examples from The Met Collection show how these were assembled, manipulated, and presented for retail consumption. A cel of Jiminy Cricket from the film Pinocchio (1940) (fig. 6) was cut trimmed and then adhered to a section of the original hand-painted background. A raking light image (fig. 7) clearly shows the artful arrangement to simulate a moment in the film.

Figure 6. Walt Disney Enterprises. Jiminy Cricket Sleeping on a Violin, from "Pinocchio", 1938. Gouache on trimmed celluloid applied to a watercolor background, Sheet: 8 3/4 x 8 1/4 in. (22 x 21 cm). Gift of Bella C. Landauer (50.511.9)

Figure 7. Raking light detail of figure 6, highlighting the cut and pasted cel

Backgrounds were much less plentiful than the animation cels (one background could serve for many minutes of a finished film) so, in order to sell the individual cels, many backgrounds were fabricated for this express purpose. They varied from hand-painted and airbrushed backgrounds as seen in the carefully trimmed and collaged image of Snow White with a small bird (fig. 8). This shows how the bird was extracted from a different piece of celluloid and glued into the scene.

Figure 8. Overall view showing the manufactured background and distorted celluloid. Walt Disney Enterprises. Snow White, American, ca. 1937. Gouache on celluloid with cut and pasted celluloid and paper applied to a watercolor on paper background, Sight: 6 7/8 x 9 3/8 in. (17.5 x 23.8 cm) Gift of Bella C. Landauer (Ref.LandauerDisney.3)

Figure 8. The cut and pasted bird. Walt Disney Enterprises. Snow White, American, ca. 1937. Gouache on celluloid with cut and pasted celluloid and paper applied to a watercolor on paper background, Sight: 6 7/8 x 9 3/8 in. (17.5 x 23.8 cm) Gift of Bella C. Landauer (Ref.LandauerDisney.3)

Another material used for the backgrounds was wood veneer. Some were painted to give the effect of space for the figures to inhabit (fig. 9), others were airbrushed to create shadows to give the appearance of three-dimensional setting for the figures (fig. 10). Later, the backgrounds were also commercially printed.

Figure 9. Walt Disney Enterprises. Pinocchio with Figaro, from “Pinocchio”, 1939. Gouache on trimmed celluloid applied to a painted wood veneer background. Sheet: 6 1/8 x 7 1/4 in. (15.5 x 18.3 cm). Gift of Bella C. Landauer (50.511.8)

Figure 10. Walt Disney Enterprises. Dwarfs, ca. 1937. Gouache on celluloid applied to wood veneer background, Sheet: 14 x 16 1/2 in. (35.5 x 42 cm). Gift of Bella C. Landauer (50.511.11)

Happily ever after

This close look at some of the details and materials that made this possible helps to deepen our appreciation of what was required to make these films. In addition, we can better understand the changes animation cels have gone through both from aging and changing of function, such as becoming independent artworks that were sold commercially. The films and the animation cels create a lasting legacy that continues to engage generations of viewers and inspire film makers. The refinement of the techniques necessary to make films that create characters that come alive is indebted to the technical know-how and talent of the numerous artists who designed and painted the animation cels.