Abuna (Father) Gregorius and Deir al-Surian Conservation Project Director Karel Innemée examine the roof of a monastery church in Wadi al-Natrun, Egypt, where flood water has absorbed into the walls. From the Deir al-Surian Conservation Project Facebook page, posted December 30, 2015

«As climate change shows its devastating consequences the world over, it is not only our lives that are affected, but also our collective material culture and historical sites. Egypt is one of many countries now entering the wind and rain belt. Though still famous for its sweltering summer days and mostly moderate winters, Egypt has experienced biting cold and, more significantly, torrential rain that for many Egyptians (including me) is unprecedented.»

One area that has seen heavy rainfall is Wadi al-Natrun, a desert valley ninety kilometers northwest of Cairo. Scete, as the valley is called in early Christian literature, is among the earliest Coptic Christian monastic centers in Egypt, whose venerable monasteries, with their mural paintings and libraries, still stand witness to monastic communities past and present.

One of these is the sixth-century Deir al-Surian ("monastery of the Syrians"), so named in part because for many centuries Syrian monks practiced ascetic life there along with their Coptic Christian peers. Recent flooding has caused one of the vaults of the monastery's church to collapse. Damage has also occurred to the church's mural paintings for which the monastery is best known, but thankfully conservation work is in progress. On an equally positive note, the monastery's rich library—which houses manuscripts in Arabic, Coptic, Ethiopic, and Syriac—was unscathed.

As a Kevorkian Curatorial Fellow in the Department of Islamic Art working with Late Antique material culture, especially manuscript production, from the Mediterranean region, I was thrilled to discover among the department's collection a great deal of early medieval period textual material from Egypt and, more specifically, Deir al-Surian. Coptic—derived from the Greek term aigyptos ("one from Egypt"), reflecting the name of the main sanctuary of the Egyptian Kingdom's first capital—represents the last stage of the ancient Egyptian language, which was preceded by Demotic, Hieratic, and, finally, Hieroglyphic. Written in Greek letters with about seven additional signs from Demotic, it was Egypt's vernacular language.

When Muslims overtook Egypt from the Byzantines in the seventh century, they adapted this Greek term to call Egyptians qibt. Over time, the term began to carry religious rather than geographic meaning as Egypt's Christians came to be referred to as Copts. In the eighth century, Arabic started to be used in public affairs, and around the twelfth century, as the language became increasingly predominant, church liturgy began to be conducted in Arabic, and liturgical and prayer books were increasingly accompanied by Arabic translations.

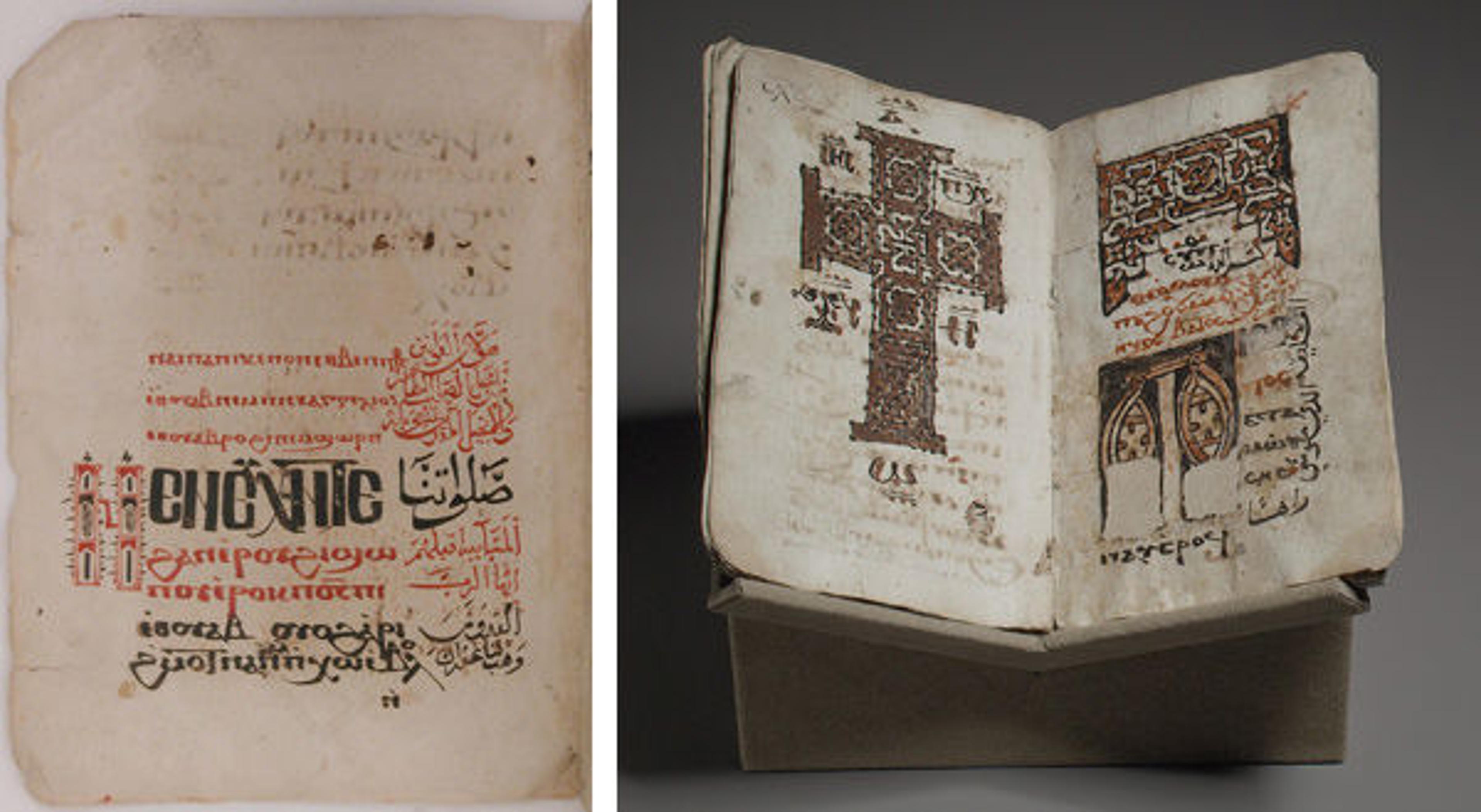

Left: Coptic prayer codex, 17th–18th century (previously attributed to the 11th–12th century). Egypt. Coptic. Black and red ink on Venetian paper; H. 8 7/8 in. (22.5 cm), W. 6 5/8 in. (16.8 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Excavations by the Egyptian Expedition of MMA, 1919 (19.196.3). Right: Illustrated Coptic liturgical codex, 17th–18th century (previously attributed to the 8th–9th century). Egypt. Coptic. Ink and colored inks on Venetian paper; Overall (closed): L. 6 1/8 in. (15.5 cm), W. 4 1/4 in. (10.8 cm), D. 1/2 in. (1.3 cm); Overall (open on book mount): H. 6 1/8 in. (15.5 cm), W. 7 15/16 in. (20.2 cm), D. 6 7/8 in. (17.4 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Excavations by the Egyptian Expedition of MMA, 1919 (19.196.5)

The manuscripts above are examples of the textual material from Deir al-Surian that are now part of the Islamic department's collection. The Museum obtained eighteen manuscripts following an excavation by its team at Deir al-Surian in 1919, but we do not know whether these codices were found at the site or acquired nearby. The prayer book, whose first page is shown at left, is a collection of morning and evening prayers as well as comments on when they should be recited, written in Coptic and accompanied with Arabic translation in the right margin (as with the liturgical codex on the right).

The prayer codex had been dated to the eleventh to twelfth century. However, when I examined the forty-four pages of this manuscript, what caught my eye was not the inclusion of both Coptic and Arabic texts, but rather the watermarks and countermarks (the initials of the paper workshop, a standard sign in Western paper production), which indicated that the manuscript could not possibly date to this period.

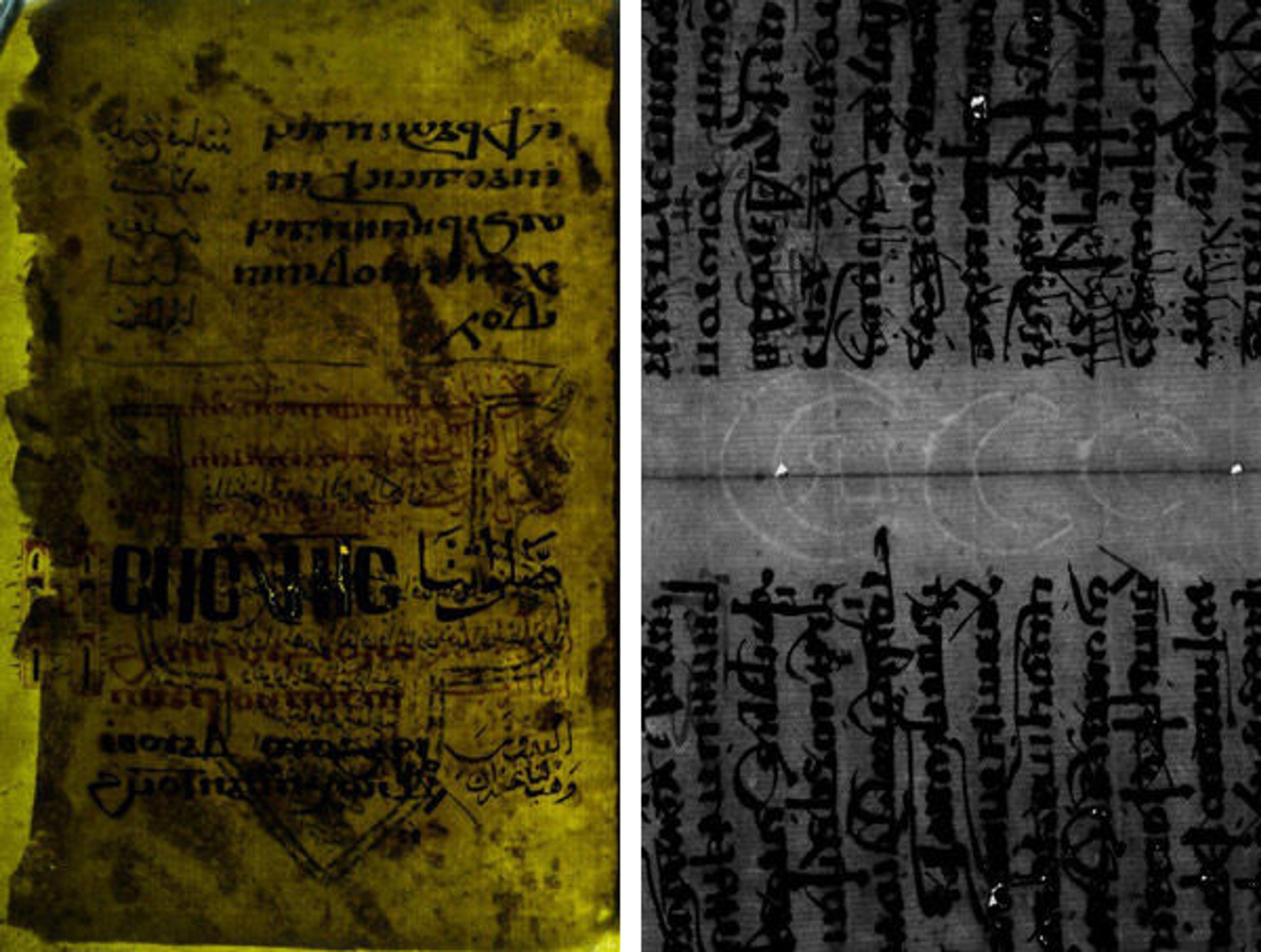

In this manuscript, we have not only the tre lune, or three crescents, on almost every other page, sometimes with the initials "LR," but also two crowns, a honeycomb shape topped with a cross, and a six-sided star with a lune. My close examination of the watermarks demonstrates that the paper belonged to a seventeenth/eighteenth-century Venetian papermaking workshop (though, admittedly, crown watermarks typically appear on paper produced in seventeenth-century French mills). We know that the Mediterranean region was a large market for Venetian paper, especially that bearing the tre luna, which can be found in many Ottoman manuscripts from the region, particularly in Egypt.

Two detail views of 19.196.3 using backlit photography, showing a flyleaf containing the colophon (left) and the tre lune watermark with the initials "LR" (right). Photographs by Alzahraa K. Ahmed and Tom Vinton

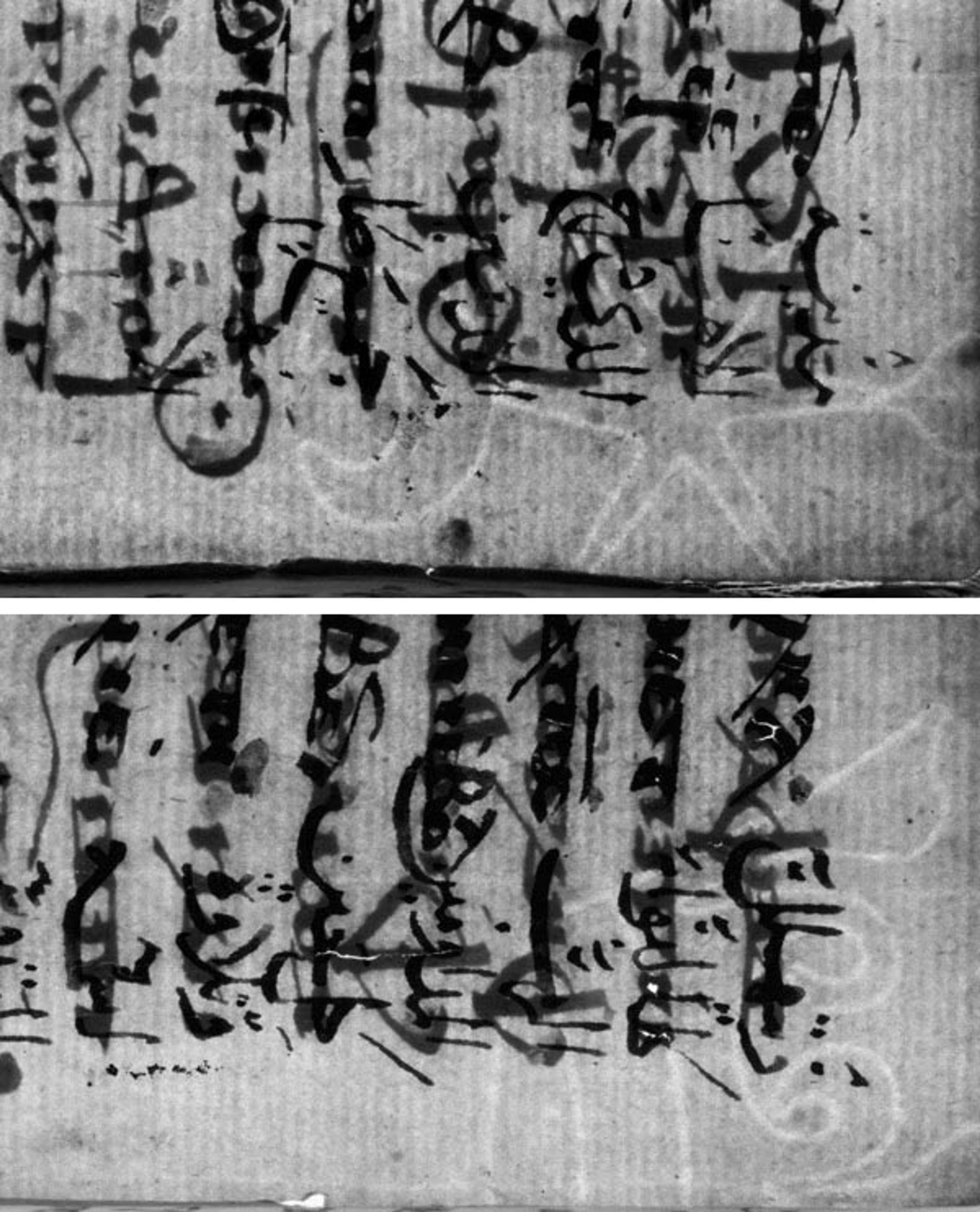

I also realized that the flyleaf glued to the first folio of the codex has an Arabic colophon stating that the manuscript is a copy of an earlier version. I wondered whether I would arrive at the same results if I were to analyze other manuscripts in the group. On inspecting the liturgical codex seen above right, I did indeed, and I found the same exact watermarks throughout, only this time with the initials "IR." Clearly an eighth/ninth-century dating is inconceivable.

Two detail views of 19.196.5 using backlit photography, showing a six-sided star with a lune watermark (top) and a half-crown watermark (bottom). Photographs by Alzahraa K. Ahmed and Tom Vinton

The stars were aligned when I saw the three crescents, and my findings were further supported when I discovered afterward that Metropolitan Museum conservator Yana van Dyke—who carried out fantastic conservation work on the manuscripts—first noticed the watermarks almost ten years ago. While the manuscripts are not of an early date, they highly resemble their predecessors; as such, they are evidence of the continuity of venerated handwriting and copying traditions. Wadi al-Natrun, long an important Christian pilgrimage site, was a center of book production and literary texts that is critical to our understanding of Christian manuscript production, including in the Islamic period.

The Coptic monk Father Yehnes al-Suriani takes a selfie with other monks in a boat while evacuating their rooms after rains flooded their Syrian monastery. From Father Yehnes al-Suriani's Facebook page, posted November 7, 2015

The region's historical importance is all the more reason to take seriously the environmental issues it faces. Whereas the monks of Wadi al-Natrun once assembled and recorded textually their collection of sayings, a genre called the "Sayings of the Desert Fathers," today's monks recorded their evacuation from their living quarters due to flooding in a genre I like to call the "Selfies of the Desert Fathers"!

Related Links

RumiNations: "The Art of Marbled Paper: Dynamic Fluids in Flow" (June 23, 2015)

Byzantium and Islam: Age of Transition Exhibition Blog