Featured Catalogue: The American West in Bronze, 1850–1925

The American West in Bronze, 1850–1925, by Thayer Tolles and Thomas Brent Smith, features 222 full-color illustrations and is available in The Met Store.

«To coincide with the opening of the exhibition The American West in Bronze, 1850–1925, Thayer Tolles—the Met's Marica F. Vilcek Curator of American Paintings and Sculpture in The American Wing—has coauthored an evocative catalogue that explores the themes of the Old West as brought to life in enduringly popular sculptures. The publication includes new photography, essays that consider the complex role artists played in constructing the public perception of the West, and an illustrated chronology of historical and artistic events.»

Below is a sampling of the artworks included in the exhibition, as well as excerpts from the catalogue's varied essays.

Charles M. Russell (American, 1864–1926). Buffalo Hunt, 1905 (cast 1905). Bronze; 10 x 19 x 12 3/4 in. Amon Carter Museum of American Art, Fort Worth, Texas (1962.121)

Out there, after overcoming every obstacle that lay between the seeker and the goal, was eternal happiness in a mythic home for heroes. "The West of the imagination," as William H. Goetzmann called it, was everything an American idea should be. Deeply rooted in European culture, it was nevertheless unburdened by the past. It was all hope and yearning, enticing and elusive. The West was a process, not a place, and thus unattainable. It retreated before the seeker like a phantom, the artist George Catlin observed in 1833, flying "before us as we travel, . . . our way . . . continually gilded, before us, as we approach the setting sun." For most nineteenth-century Americans, the real West where ordinary people lived out their lives may not have mattered much; but as an idea, the West was charged with meaning.

—From the essay "Western Dreams and Buckskin Fantasies" by Brian W. Dippie, Professor Emeritus of History, University of Victoria, British Columbia

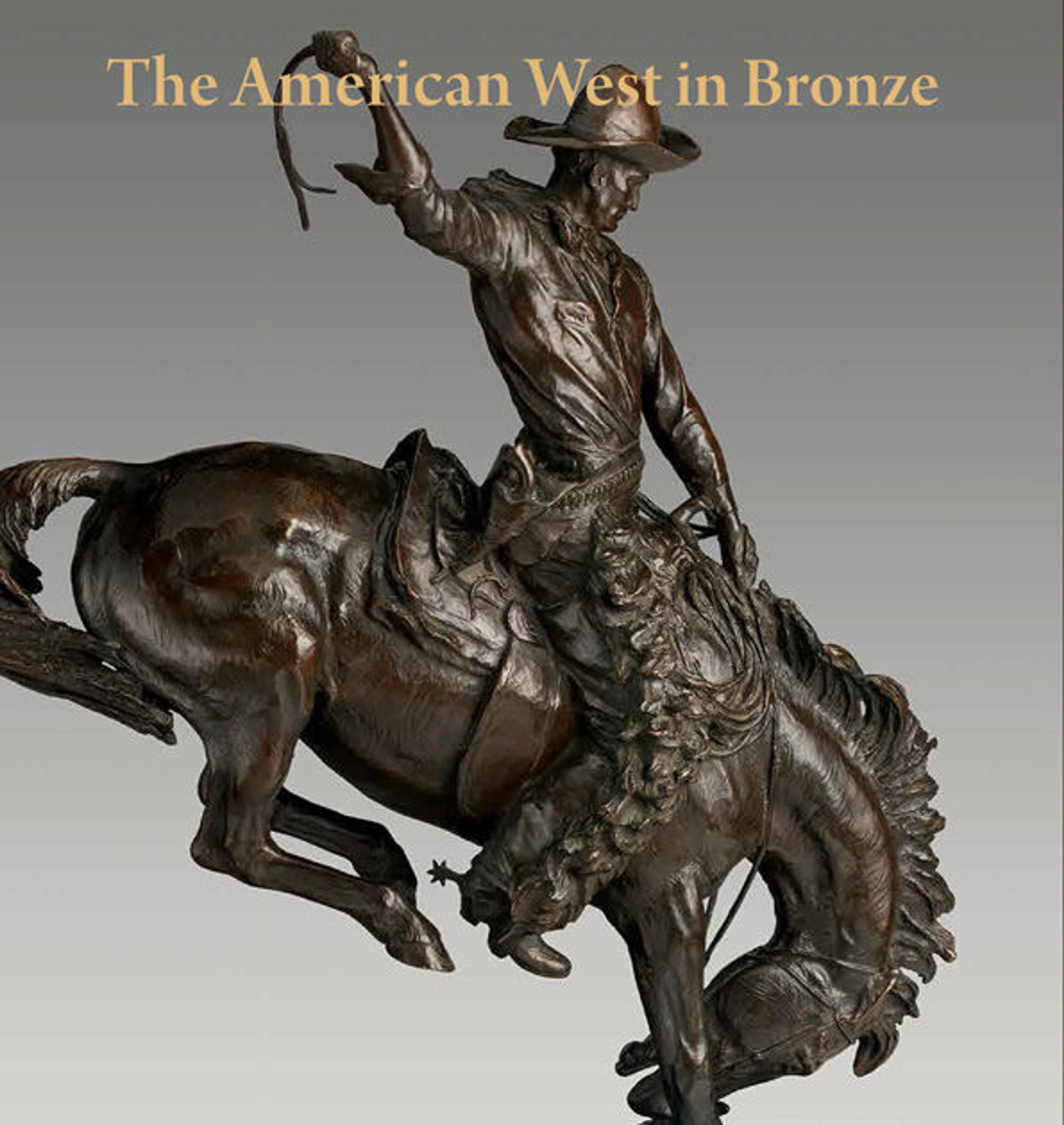

Frederic Remington (American, 1862–1909). The Broncho Buster, 1895 (cast 1906). Bronze; 22 5/8 x 22 3/4 x 15 1/4 in. The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, The Hogg Brothers Collection, gift of Miss Ima Hogg (43.73)

Solon Hannibal Borglum (American, 1868–1922). Lassoing Wild Horses, 1898 (cast ca. 1900–1902). Bronze; 31 3/4 x 19 3/4 x 33 1/4 in. National Cowboy & Western Heritage Museum, Oklahoma City, Museum Purchase (1972.20)

Lassoing Wild Horses was Borglum's first major sculpture. . . . The work focuses not on the wild horse that was being captured, as suggested in the tension of the rope that extends from the lead rider's right side, but on the concordance of the two cowboys. With this sculpture, Borglum rose to fame meteorically in the United States. He was introduced as a prophet of the prairies and as "the first . . . to produce sculpture that was both truly western and truly art."

—From the essay "Cowboys in Bronze" by Peter H. Hassrick, Director Emeritus and Senior Scholar, Buffalo Bill Center of the West, Cody, Wyoming; and Director Emeritus, Petrie Institute of Western American Art, Denver Art Museum

Arthur Putnam (American, 1873–1930). Prospector, 1903 (cast ca. 1921). Bronze; 11 x 8 1/2 x 8 1/2 in. Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, Gift of Alma de Bretteville Spreckels (1924.119.1)

The tactile modeling, undulating surface, and exaggerated musculature of Prospector appear to have been influenced by the French sculptor Auguste Rodin, whose work had been on view in San Francisco and whom Putnam would meet in Paris in 1906. Rodin and many of his followers were interested in the physical and emotional toll of labor, and Putnam's small model depicting a prospector squatting next to his pickax is as much about the ethos of labor as it is about the gold rush.

—From the essay "Settling the West: Fearless Men and Strong Women" by Thomas Brent Smith, Director, Petrie Institute of Western American Art, Denver Art Museum

Alexander Phimister Proctor (American [born Canada], 1860–1950). Pursued, 1914. Bronze; 17 3/4 x 24 1/8 x 6 1/2 in. Charles and Barbara Griffith

Adolph Alexander Weinman (American [born Germany]), 1870–1952. Chief Blackbird, the Ogalla Sioux, 1903. Bronze; 16 3/8 x 12 1/2 x 11 1/2 in. Brooklyn Museum, Gift of George D. Pratt (15.512)

Sculptors [ . . . ] chose to present Indian men in bronze not as they then lived but as first inhabitants of a land they were destined to relinquish. Shown hunting, performing rituals, fighting, dying in battle, or otherwise surrendering to their fate, bronze Indians acquired a patina of nobility.

—From the essay "Indians on the Mantel and in the Park" by Carol Clark, William McCall Vickery 1957 Professor of the History of Art and American Studies, Amherst College, Amherst, Massachusetts

Henry Merwin Shrady (American, 1871–1922). Buffalo, 1899 (cast ca. 1901). Bronze; 14 x 13 1/2 x 10 in. Amon Carter Museum of American Art, Fort Worth, Texas (1999.21)

Nearly every sculptor of western themes, whether an animal specialist or not, at some point modeled the bison. Perhaps the most remarkable in terms of its naturalism and quality of casting is Henry Merwin Shrady's Buffalo . . . He convincingly recorded the bison's solid form, rendering its weighty coat as a textural tour de force. . . . Remington was so impressed by Shrady's Buffalo, . . . that he purchased an example in 1908, calling it "bye [sic] and large the best buffalo I ever saw modeled and it has become one of the things that I had to own." Unlike sand casting, the lost-wax process allowed for refinements to the wax model, which gave sculptors freedom to make changes, experiment, and lavish care on details, as Shrady did here.

—From the essay "Preserved in Bronze: The West's Vanishing Wildlife" by Thayer Tolles

Frederic Remington (American, 1861–1909). Coming through the Rye, 1902 (cast 1907). Bronze; 29 x 31 x 27 1/4 in. Buffalo Bill Center of the West, Cody, Wyoming, Gift of Barbara S. Leggett (5.66)

With his sculptures, Remington had breathed new life into the cowboy hero. In 1902 he copyrighted his raucous foursome, Coming through the Rye, which introduced many to a radically different image of the cowboy—a brawling horseman of the plains. The composition and the theme of cowboys as rowdy hooligans had been born as an illustration, The Dissolute Cow-Punchers, for one of the early Roosevelt stories in 1888. Roosevelt had referred to this as "mere horse-play . . . the cowboy's method of 'painting the town red,' as an interlude in his harsh, monotonous life." Western towns, though, viewed such activity in quite another light. Livingston, Montana, for example, regarded a cowboy "shooting off his mouth and his revolver" as "an unmitigated nuisance, and an offender against the public peace." In Arizona the problem had gotten so severe in the early 1880s that President Chester A. Arthur threatened to call out the cavalry. Charlie Siringo, who in 1886 published one of the more credible memoirs of cowboy life, came to the defense, saying that the "wild and wooly" members of his fraternity were mostly imaginary because that was how "eastern people" had them "pictured." Remington was certainly trying to please eastern audiences, and whether it was pure invention or reality based in some way, Coming through the Rye presented a popular trope.

—From the essay "Cowboys in Bronze" by Peter H. Hassrick

Related Links

The Met Store

American West in Bronze exhibition blog

Nadja Hansen

Nadja Hansen was formerly an editorial assistant in the Editorial Department.