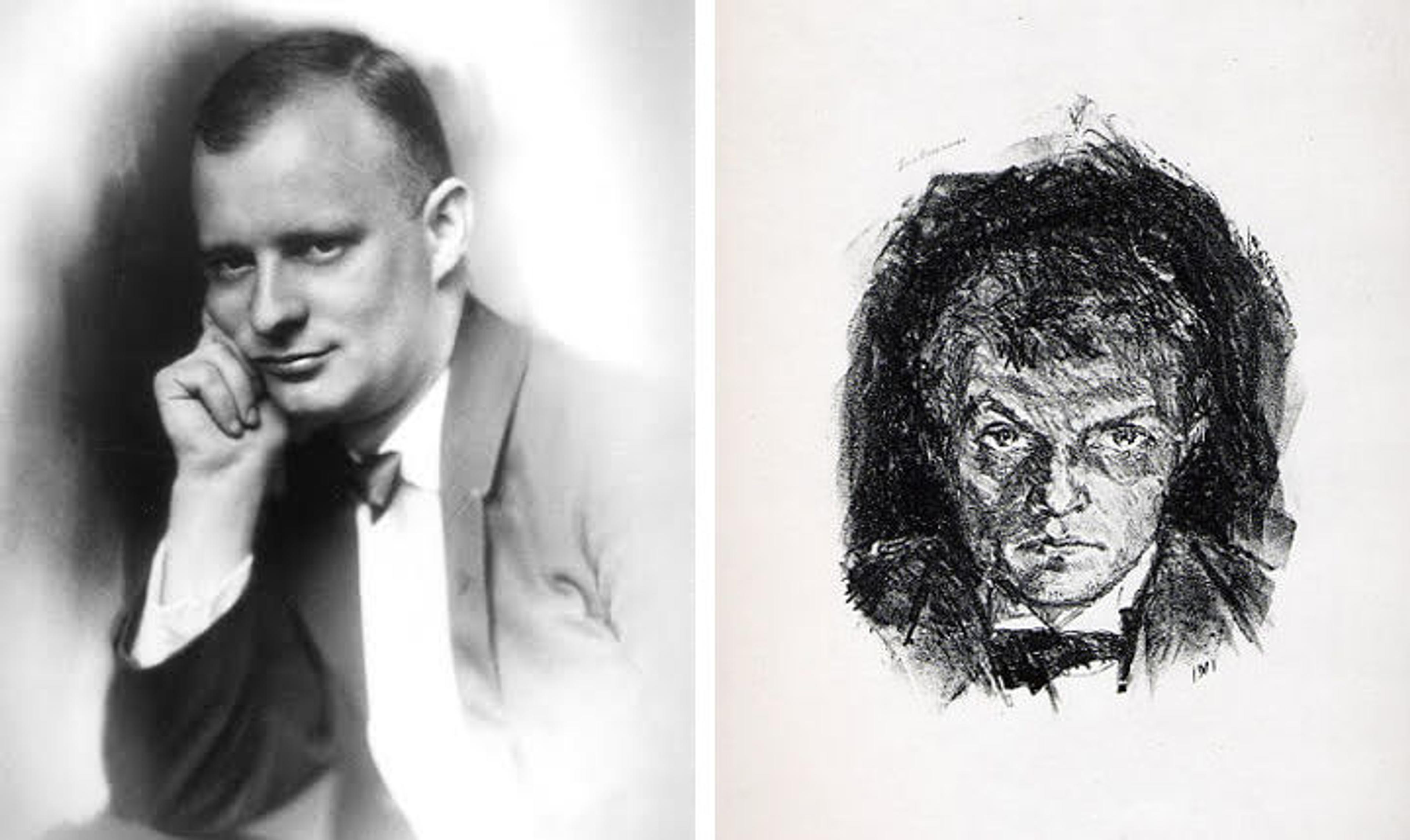

Artists in Exile: Paul Hindemith and Max Beckmann

Left: Paul Hindemith, 1923. Licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons. Right: Max Beckmann (German, 1884–1950). Self-Portrait, 1911. Lithograph, H. 17 1/2 x W. 14 3/8 in. (44.5 x 36.5 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Anonymous Gift, in honor of Reba White Williams, 1996 (1996.208) © 2016 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

«As a result of their brutal quest to reform all of German culture, the Nazi regime not only brought about a depression in the countrywide production of new art but also caused a mass exodus of Germany's finest artists, composers, and writers. Among those to leave due to official condemnation were the composer Paul Hindemith and the artist Max Beckmann, who fled to other areas of Europe in 1937—Hindemith to Switzerland and Beckmann to the Netherlands—before ultimately finding refuge in the United States. In America, both men found avenues for work through teaching: Hindemith was a composition professor at Yale University (he even performed at several of The Met's series of Members concerts as conductor of the Yale Collegium Musicum); and Beckmann held positions at Washington University in Saint Louis and, later, the Brooklyn Museum Art School.»

Left: Hindemith (standing, wearing a white shirt) and the Yale Collegium Musicum rehearse in The Met's Arms and Armor Court before a concert in May 1948

In many ways, the output of Hindemith and Beckmann share similar perspectives, many of which will be highlighted on October 16 in the next concert in the Sight and Sound series, Hindemith and Beckmann: Expressionism and Exile, presented in conjunction with the exhibition Max Beckmann in New York, opening October 19, 2016. In addition to a performance of Hindemith's Mathis der Maler Symphony by Leon Botstein and The Orchestra Now, the event will also feature a discussion of Beckmann's work and a question-and-answer session.

The political climate in Nazi Germany sparked an interest in Hindemith to compose an opera based on the life of the painter Matthais Grünewald—specifically the artist's struggle for freedom of expression during the German Peasants' War of 1524–25, in which the country's impoverished serfs revolted against their wealthy feudal lords. The plot of the opera, Mathis der Maler (Matthais the Painter), conflicted deeply with Nazi ideology, which called for the government to dictate cultural trends to ensure the elimination of formalism and the avant-garde. At the opera's 1938 premiere, Hindemith described exactly why Grünewald's work resonated with him, stating:

. . . [Grünewald's] paintings tell us vividly how the wild times with all their misery, their illnesses, and their wars unnerved him. How bottomless must have been the abyss of fickleness and despair that he navigated when, at the threshold of modern times, he gave intimate expression one more time to medieval piety . . .[1]

Hindemith was in the initial stages of composing his opera when the conductor Willhelm Furtwängler commissioned the composer, in 1934, to write a new work to be performed by the Berlin Philharmonic. Wanting to devote all of his efforts to the opera, Hindemith decided to create three movements that could later serve as orchestral interludes in the stage work. Greatly inspired by Grünewald's most famous work, the Isenheim Altarpiece (now in the collection of the Museum Unterlinder in Colmar, France), each of the symphony's three movements is based on a section of the altarpiece: the first movement, Engelkonzert (Concert of Angels), is the scene of Mary and the baby Jesus being serenaded by angels portrayed on the outer doors; Grablegung (Emtombment) refers to the burial of Jesus after his crucifixion seen on the bottom panel; and Versuchung des heiligen Antonius (Temptation of Saint Anthony), a symphonic fever dream in which Saint Anthony is tormented by a horde of grotesque demons as seen when the inner doors of the altarpiece are fully opened.

Mathis Gothart Nithart (Grünewald) (German, 1475/80–1528). Isenheim Altarpiece (view with outer wings opened), 1512–16. Mixed media (oil and tempera) on limewood panel. Museé Unterlinden, Colmar

Despite being a progressively tonal work, Hindemith incorporated numerous folk songs and hymns throughout, including the medieval song "Es sungen drei Engel" (Three Angels Were Singing) during the first movement, and a 13th-century chant, "Lauda Sion Salvatorem" (Praise, O Zion, Thy Savior), in the final movement, which is then answered by a number of alleluia refrains in the brass. The sense of nationalistic reverence that should have been highlighted by Hindemith's inclusion of these German songs fell on the deaf ears of the Nazi leaders, though, and Propaganda Minister Joseph Goebbels quickly deemed the work "degenerate" and denounced Hindemith for "cultural Bolshevism." As such, Hindemith could not get the opera produced in Germany, and the stage work did not receive its premiere until 1938 in Switzerland.

Like Grünewald, Beckmann had also been unnerved by the horrors of war he witnessed. After serving voluntarily as a medic in World War I, Beckmann later channeled his visions of warfare into emotionally charged and keenly vivid scenes of terror—which had previously been depicted only by the likes of Grünewald and Hieronymous Bosch—wherein he mixed reality, dreams, mysticism, and mythology into his work. He also turned to the triptych throughout his career, creating 10 such works that successfully translated the sacred medieval form into an avenue for his modern, secular allegories.

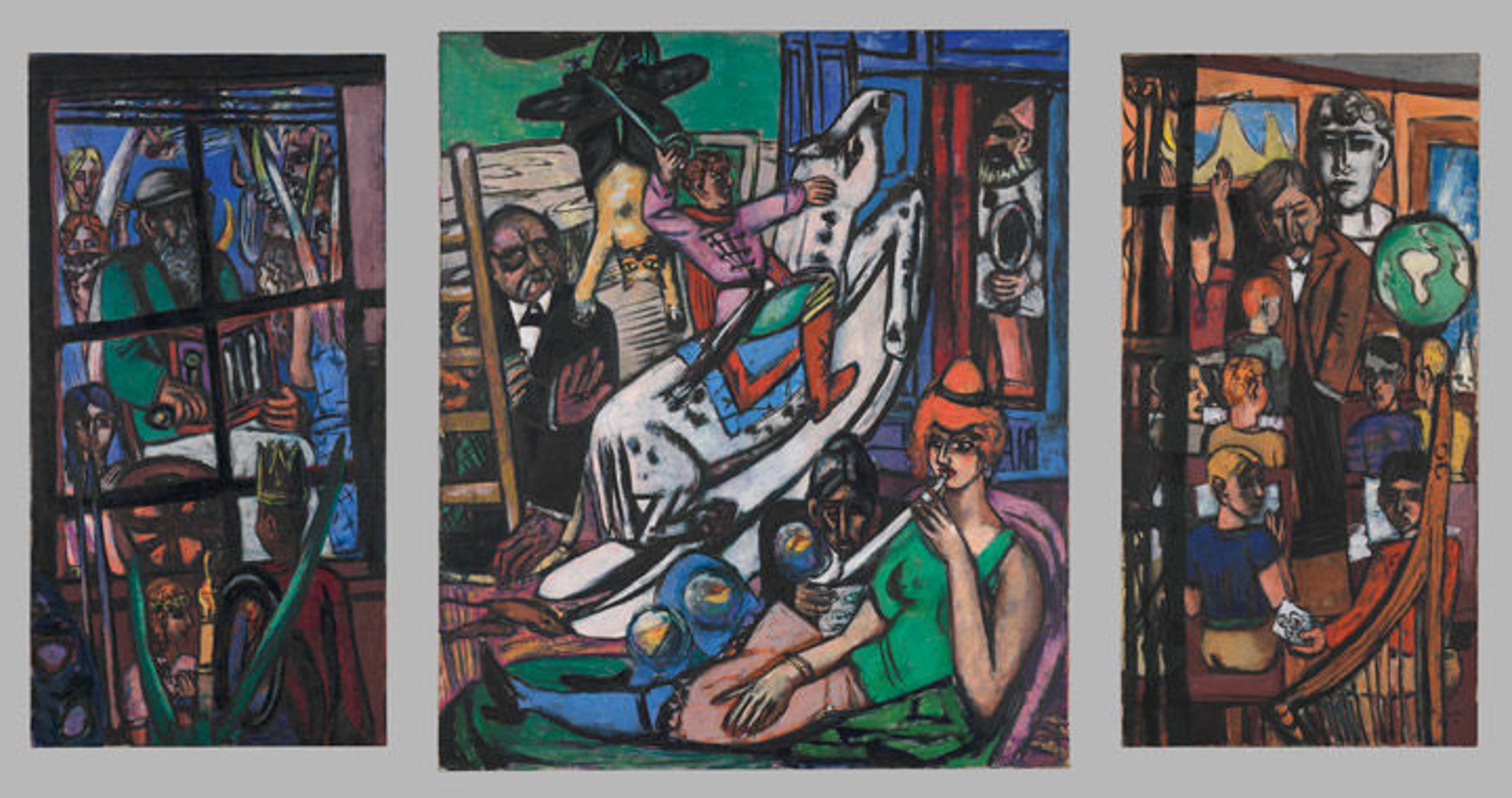

One such triptych now in The Met collection, The Beginning, showcases Beckmann's synthesis of fantasy and reality. Completely autobiographical in nature, the right panel depicts an everyday scene of his childhood classroom in Germany and the left panel evokes a dream state in which Beckmann, as a child, looks out his window to see a series of winged women and one sinister-looking man; meanwhile, the central panel seamlessly merges the fantasy and reality presented in the outer scenes.

Max Beckmann (German, 1884–1950). The Beginning, 1949. Oil on canvas, Overall: 69 x 125 1/2 in. (175.3 x 318.8 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Bequest of Miss Adelaide Milton de Groot (1876–1967), 1967 (67.187.53a-c) © 2016 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Beckmann became the ire of Hitler's government as swiftly as Hindemith. In 1933 the artist was dismissed from his teaching position at Frankfurt's Städel School, and 28 of his paintings and more than 500 works on paper were systematically removed from display in the country's museums. On the same day that the notorious Nazi-sponsored exhibition of "degenerate art" opened in Munich in 1937, Beckmann traveled to Amsterdam with his wife, Quappi, where he remained until he was able to receive a visa to move to America in 1947.

Although he was incredibly prolific during his years in exile, creating more than 250 paintings while holding teaching posts, Beckmann's abrupt departure from his homeland proved humiliating to the artist, especially given the success he had achieved and the praise with which he had been hailed just before his denouncement. Unfortunately Beckmann's time in New York City was brief, as he suffered a heart attack in 1950 near his Upper West Side apartment while en route to The Met, where he was eager to see a recently completed work of his exhibited in the Museum.

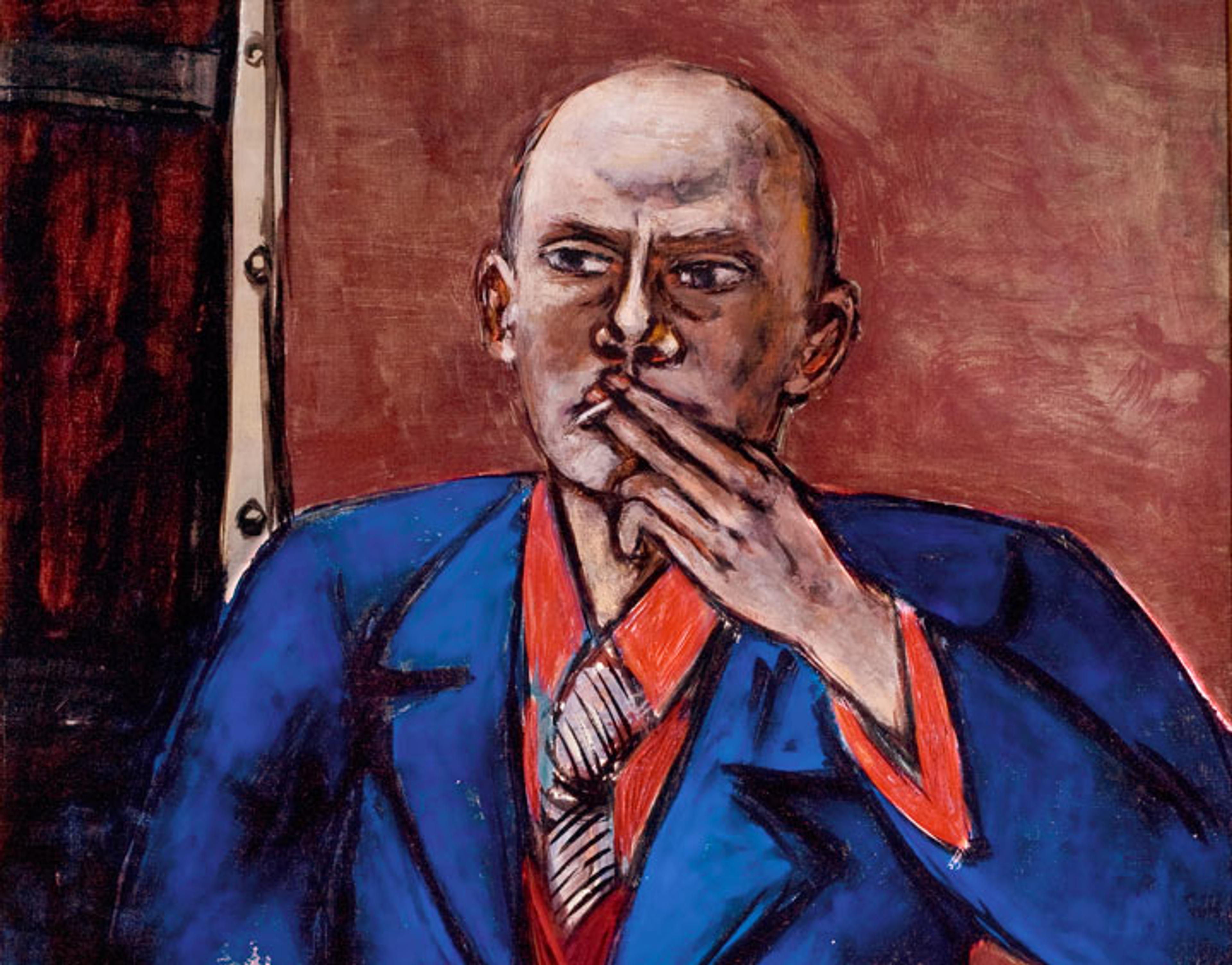

That work, Self-Portrait in Blue Jacket—now in the collection of the Saint Louis Art Museum in the artist's adopted city of two years—will be on view in Max Beckmann in New York, where Beckmann's icy stare will speak volumes to visitors who are still wrestling with the same themes of humanity's angst: the persistent threat of war, the subjugation of religious and minority groups, and the rise of authoritarian states in otherwise progressive and culturally rich societies.

Max Beckmann (German, 1884–1950). Self-Portrait in Blue Jacket (detail), 1950. Oil on canvas, 55 1/8 x 36 in. (140 x 91.4 cm). Saint Louis Art Museum, Bequest of Morton D. May. © 2016 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn

Note

[1] Paul Hindemith, "Zur Einführung," in Festheft zur Uraufführung im Stadttheater Zürich, trans. Siglind Bruhn (Zurich: May 28, 1938), 3–5.

Related Links

Max Beckmann in New York, on view at The Met Fifth Avenue from October 19, 2016, through February 20, 2017

The Artist Project: "Eric Fischl on Max Beckmann's Beginning"

Michael Cirigliano

Michael Cirigliano II is the managing editor in the Digital Department.