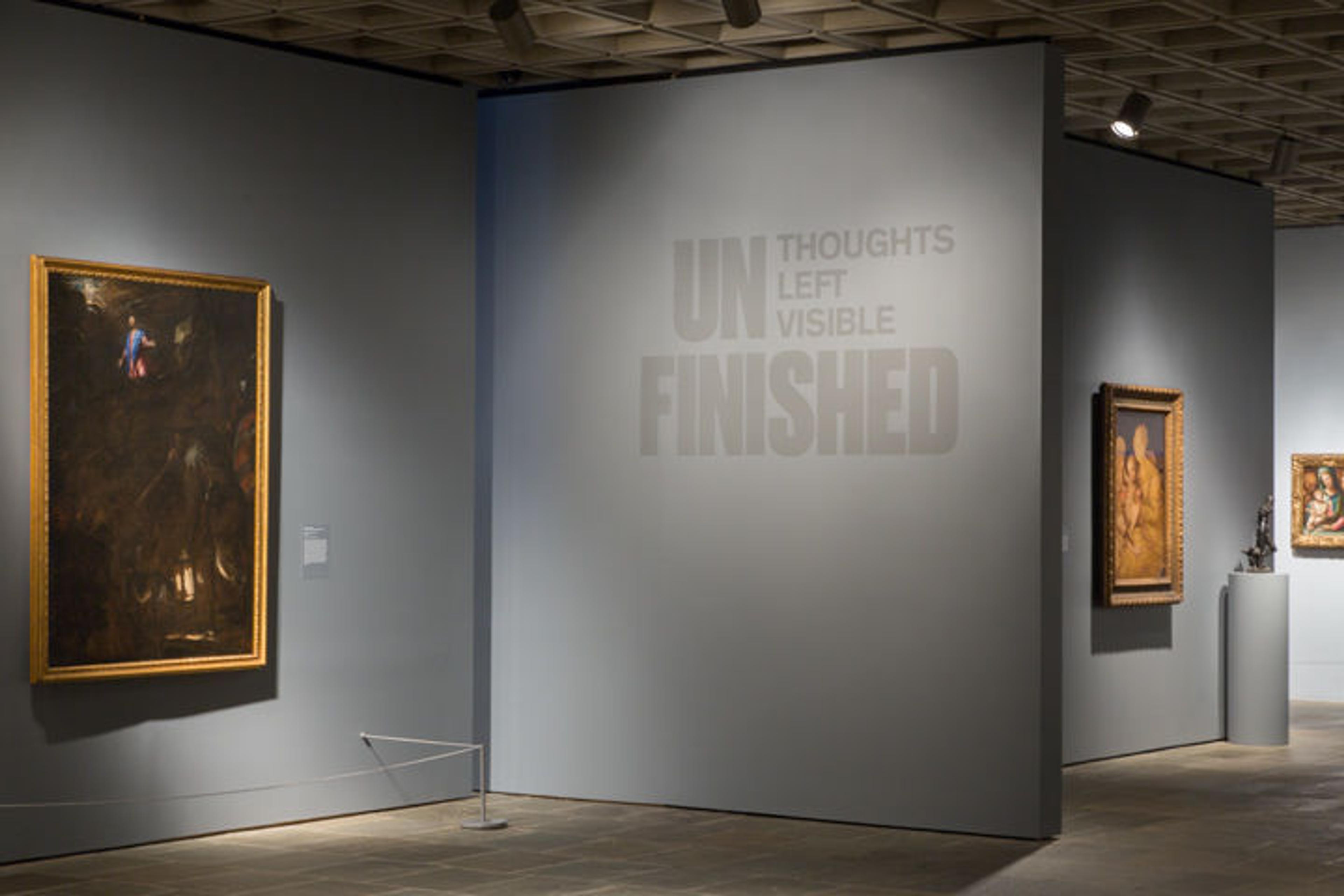

Gallery view of the exhibition Unfinished: Thoughts Left Visible, on view at The Met Breuer through September 4, 2016

«Many works of art are mysteries asking to be deciphered. In the inaugural exhibition at The Met Breuer, Unfinished: Thoughts Left Visible, some of the mysteries are more subtle, some more obvious, and some profound, but all are engaging. As part of the opening-weekend celebrations for the Museum's new location, I led two of the "9-Minute" talks—nine minutes being the time it takes to walk from The Met Fifth Avenue to The Met Breuer—that focused on various works on view in the exhibition.»

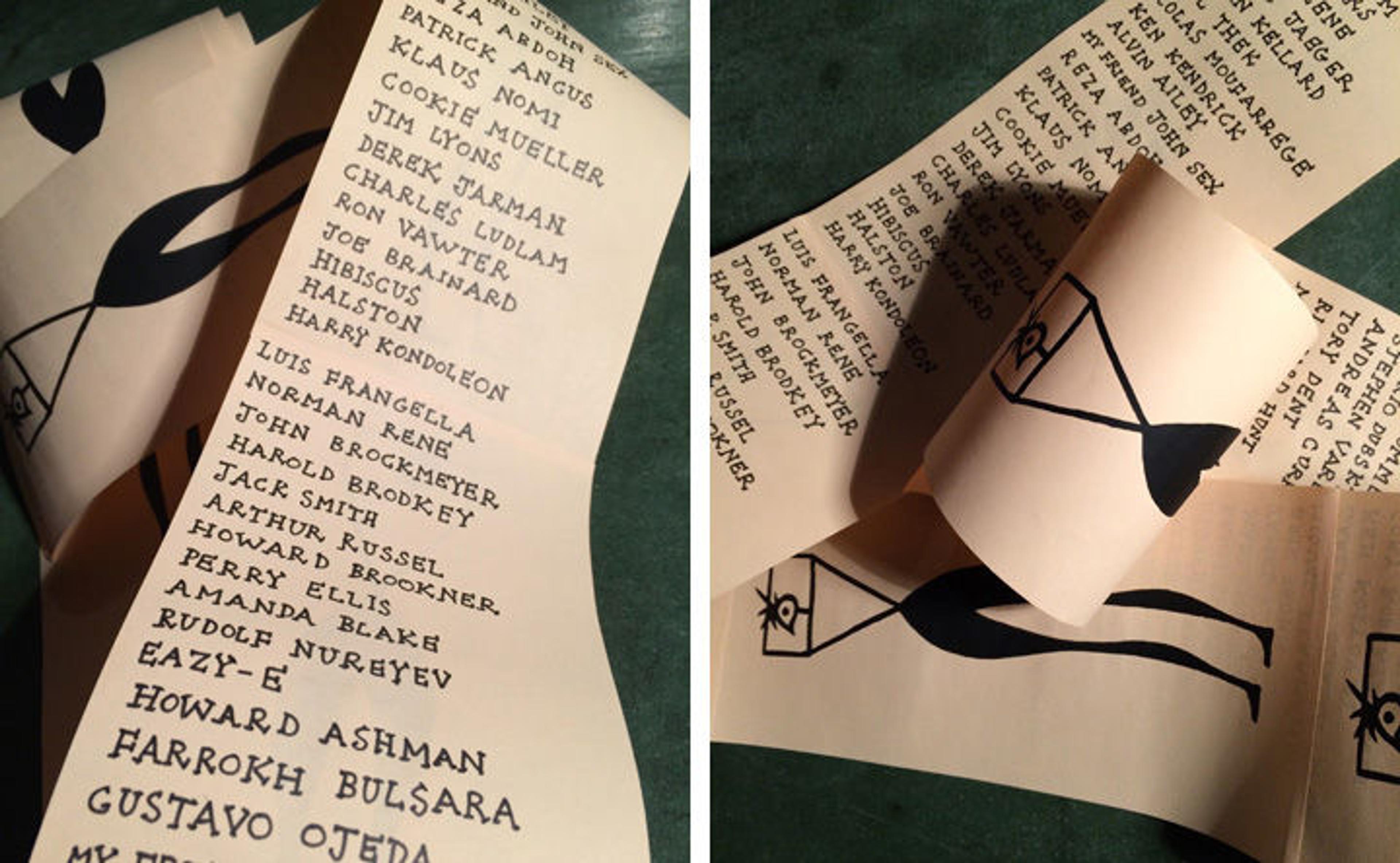

For my first talk, I briefly commented on Untitled (Portrait of Ross in L.A.) by Felix Gonzalez-Torres, a complex and loaded work that functions on many levels, and exactly the kind of work that I love. The piece, an approximately 175-pound mound of cellophane-wrapped hard candy, is a tribute to a lost lover, a critique of the social and political complicities that contributed to his demise, and a reference to religious rituals. While this intense work can certainly be talked about at length, I chose instead to recite a list of the names of artists and creative individuals (all of whom I considered to be part of my community) lost during the early years of the AIDS crisis. I then asked the audience to reflect on not only unfinished works but also on unfinished lives.

Peter Hristoff. Unfinished Scroll, 2016. Photos courtesy of the author

The following morning, I spoke about The Assumption of the Virgin by Frederico Barroci (ca. 1535–1612), another work that is complex on multiple levels. Embarrassingly, I had never heard of Frederico Barroci, who may also be one of the most famous artists that you never knew existed.

Born in Urbino, Barroci was an early master of the Italian Baroque who was greatly admired in his lifetime and envied for his talent, facility, and fame. Religious, disciplined, and taciturn by nature, Barroci was convinced that rivals had poisoned him while he was working on a commission in Rome. After the alleged incident of poisoning, Barroci was ill for three years, and was truly convinced that it was his constant praying to the Virgin Mary that restored his health. This combination of religious devotion, social anxiety, and self-acknowledged artistic greatness made him a recluse and, over time, compromised his reputation. Today his reputation is somewhat limited to scholars and art historians, perhaps because he remained a local artist, rarely leaving Urbino for the duration of his professional life.

Frederico Barroci (Italian, ca. 1535–1612). The Assumption of the Virgin, 1604–1605. Oil on canvas; 94 1/8 x 67 5/16 in. (239 x 171 cm). Galleria Nazionale delle Marche, Urbino

The composition of this painting is typical of Barroci: tiers of figures building up to the main subject, in this case the Virgin Mary during her assumption to Heaven. In comparison to his other works, this painting is barely more developed than a sketch—but with that said, what a painting! Barroci keeps his vision fresh and engaging; the figures are fluid, and in the more complete sections we see a use of color and light that is only a glimpse of what he accomplishes in his finished works. One can view the unfinished quality of this painting as a parallel to religious belief and faith, that what is suggested becomes more real than what is rendered. The "unfinished" quality of this work is what makes it alive.

Here we tap into Barroci's profound sense of faith, how religious ideas are suggestions and promises for some while others consider these as absolute and "finished" fact. He seems to be asking viewers how long a complex scene or thought can be held before it morphs into its next state. I like to think of this work along the lines of the Giotto-esque character in Pier Paolo Pasolini's The Decameron, who, at the end of the movie, says: "Why complete a work when it's so beautiful just to dream it?" This could easily be the mantra of this exhibition.

I work on multiple pieces at once, and oftentimes my production cannot keep up with my ideas and interests. The paintings that are set aside say enough, and I feel comfortable in allowing them to rest. Coincidentally, the subject of the unfinished and ideas of completion are a fundamental premise of the installation I have been working on over the course of my residency: recreating the works I admire at The Met, an impossible task to finish.

Peter Hristoff. My Met, 2015–. Photo courtesy of the author

I believe that the quality of a work having "more than enough" is often what allows an artist to set it aside. Leaving something unfinished can imply confidence, an intention to return to the piece, or complete rejection. That said, many artists I know—myself included—keep rejected work as well as unfinished work in their studios. This might be because some artists have a hard time throwing their work away, or maybe there is something an artist can gain from the potential of failure. All of this taps into faith about our collective practice, the hope of creating a body of work that says something. In any case, it is inevitably time that decides what is finished and what is not.

Related Links

Unfinished: Thoughts Left Visible, on view at The Met Breuer through September 4, 2016

Read all blog posts related to Peter Hristoff's residency at The Met.