Calling a Spade a Spade: A Lack of Uniformity in Suits and Decks

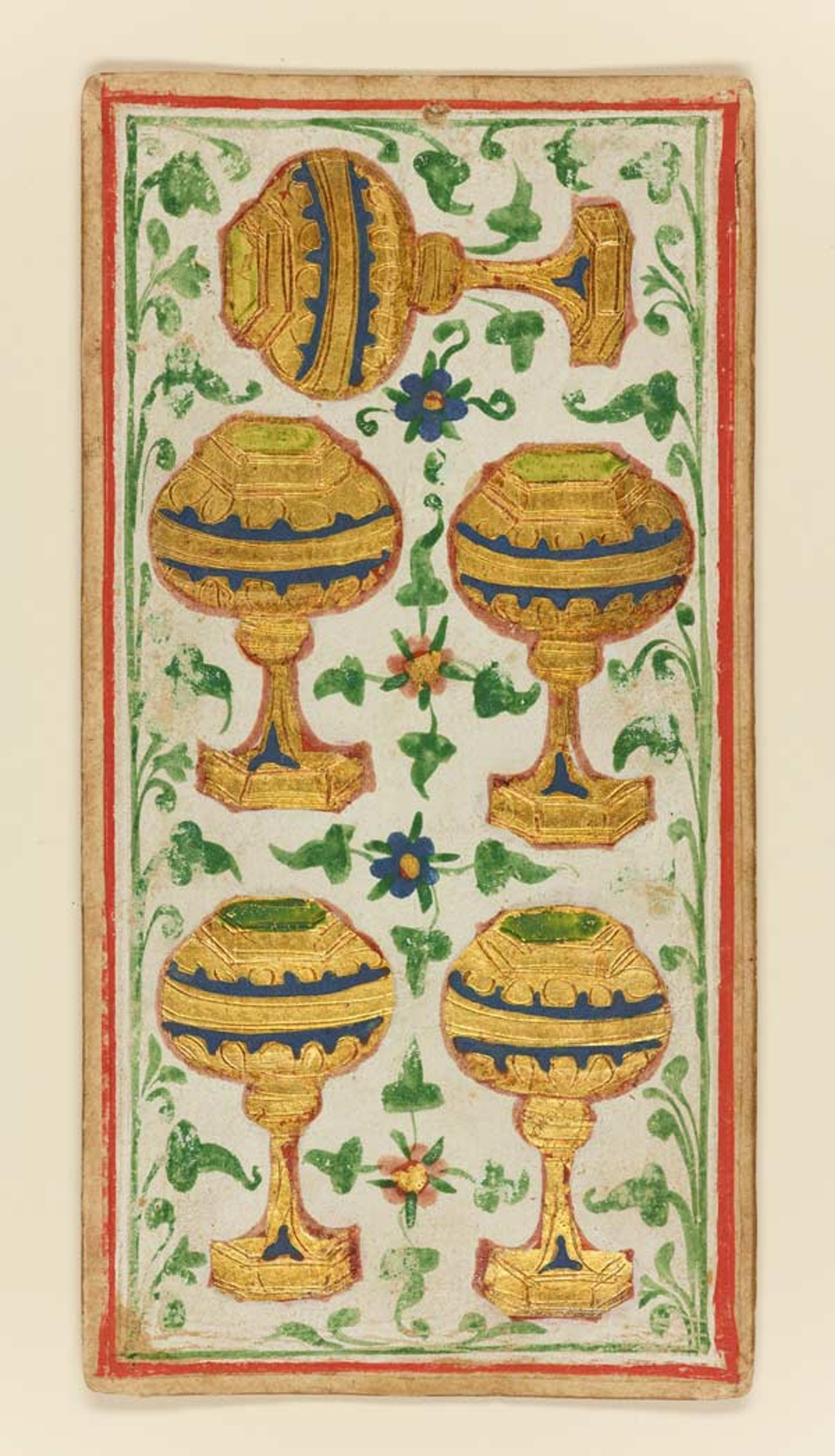

Workshop of Bonifacio Bembo (Italian, Cremonese, active by 1447/48–died before 1482). 5 of Cups, from The Visconti-Sforza Tarot, ca. 1450. Made in Milan, Italy. Paper (pasteboard) with opaque paint on tooled gold ground; 6 3/4 x 7 3/8 in. (17.3 x 8.7 cm). The Morgan Library & Museum, New York (MS M.630.26)

«Readers unfamiliar with early European playing cards will be surprised by their total lack of uniformity. In the English-speaking world, all decks of ordinary playing cards comprise fifty-two cards in four suits—Spades, Hearts, Diamonds, and Clubs, ranked in that order—with Kings, Queens, and Jacks as face cards and number (or "pip") cards from 10 through 2. Instead of a 1, there is an Ace, which has the highest value. Additionally, there are two Jokers, which are used in some games and not in others.»

The suits familiar to us were adopted from French playing cards, whose suits were standardized by the mid-fifteenth century. Suits in Italy—Cups (Coppa), Swords (Spade), Batons (Bastoni), and Coins (Denari)—were likewise in place during the same period. Decks of playing cards in late medieval Germany, which are the primary focus of the exhibition The World in Play: Luxury Cards, 1430–1540, did not have standard suit symbols or hierarchies.

None survive from earlier than about 1430, but contemporary texts suggest that the earliest cards from the fourteenth century had figures borrowed from the social structure at court: kings and queens (not always paired); knaves ( attendants or persons of low rank, as opposed to knights), usually with both an upper (ober) and a under (unter) knave; various officials and functionaries (marshals, chamberlains, heralds, and cupbearers); and members of diverse occupations (clerics, cooks, footmen, and fishmongers). All were ranked in a distinct order that was usually, but not always, indicated by numbers.

10 of Germany, Master of the Household from The Courtly Household Cards, ca. 1450. German, Upper Rhineland. Kunsthistorisches Museum Wien, Kunstkammer

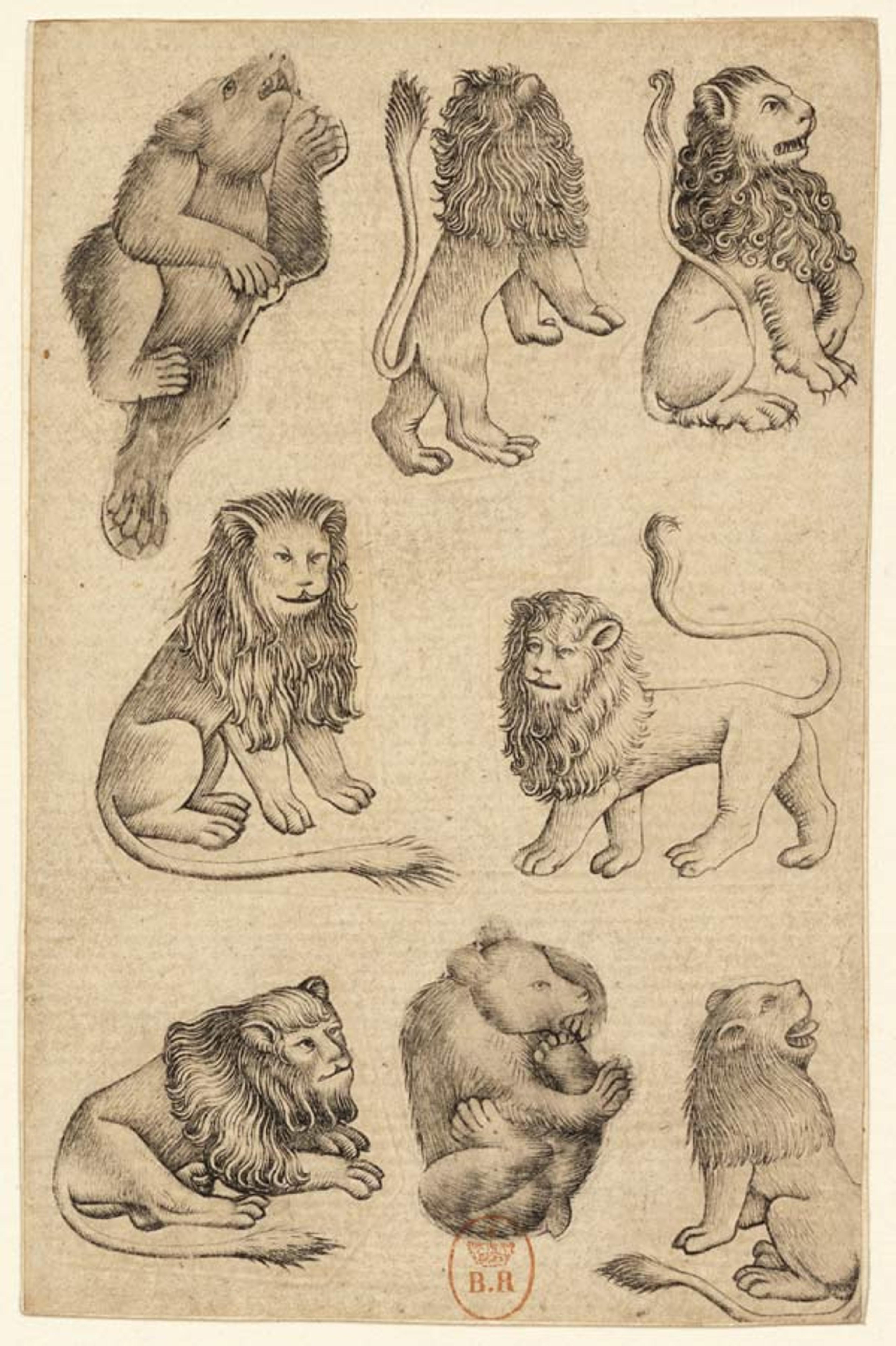

The earliest surviving cards have suits with various types of flowers and birds along with creatures associated with the hunt (Falcons, Hounds, Stags, and Bears), as well as Helmets, Shields, Swords, and Coins. Some of these suits may have been borrowed from Italian cards.

Master of the Playing Cards (German, active ca. 1425–50). 8 of Beasts, ca. 1435–40. German, Upper Rhineland. Copper plate engraving. Bibliothèque nationale de France, Paris.

The number of suits in a deck also varied at that early stage, from four, five, six, or more. The pip cards generally ran from 10 through 2, the former expressed, not with the appropriate repetition of the suit symbol, but with a banner emblazoned on it.

Banner (10) of Hounds, from The Stuttgart Playing Cards, ca. 1430. German, Upper Rhineland. Paper (six layers in pasteboard) with gold ground and opaque paint over pen and ink; 7 1/2 x 4 3/4 in. (19.1 x 12.1 cm). Landesmuseum Württemberg, Stuttgart (KK grau 39)

As the number of face cards varied and a 1 might be included or not, the number of cards in a deck ranged from forty-eight to fifty-two and, sometimes, up to fifty-six, or many more. Only in the late fifteenth century did the Germans settle on four suits: Acorns (Eichel), Leafs (Laub), Hearts (Herz), and Bells (Schelle). But even then the number of cards in a deck could still vary. To avoid confusion with modern deck structure, the terms "Jack" (roughly the equivalent of the Lower Knave), "Deuce" (2), and "Ace" (1) will not be used in this series, but there are examples of decks that include 1 in the exhibition.

Hans Schäufelein (German, ca. 1480–1540). 1 of Acorns from The Playing Cards of Hans Schäufelein, ca. 1535. Made in Nuremberg, Germany. Woodcut on paper colored with stencil; each card: 3 3/4 x 2 3/8 in. (9.5 x 6 cm). Germanisches Nationalmuseum, Nuremberg (GNM Sp 7109–7120 Kapsel 516)

With this wide range of deck and suit structures in early European playing cards, you might be wondering what types of games the cards were used for. The truth is that we don't really know, but we're able to make some educated guesses. For example, with no standardized decks, there couldn't have been codified games that could be played by all, such as we have today. Check back in for the next post in the series to find out more!

Tim Husband

Tim Husband is a curator in the Department of Medieval Art and The Cloisters.