Expanding Possibilities: Stanley William Hayter and Atelier 17

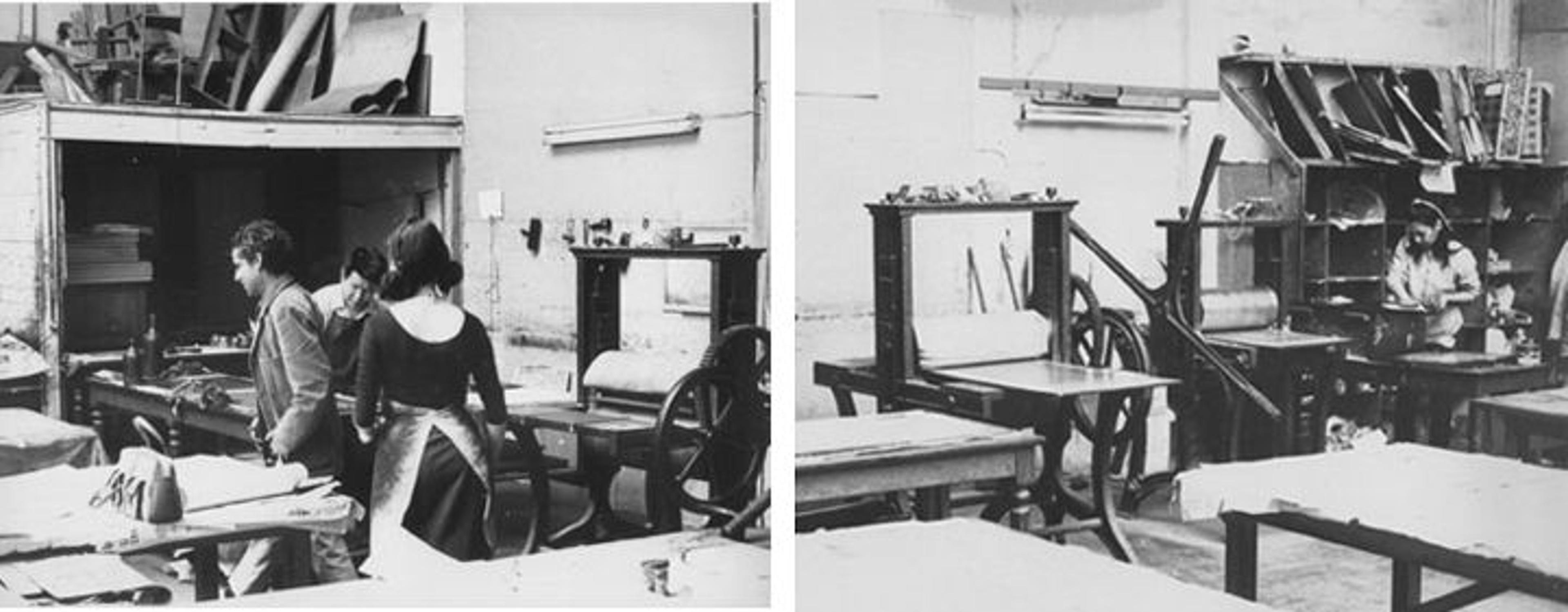

Stanley William Hayter's studio, Atelier 17, 1950s. Photos courtesy of Krishna Reddy

«Atelier 17, the celebrated print studio established by Stanley William Hayter (1901–1988) and the focus of the current exhibition Workshop and Legacy, had a profound impact on 20th-century art, specifically the graphic arts. Hayter first worked as a chemist and geologist before moving to Paris in 1926 to study art. One year later, he opened a printmaking workshop, and in 1933 he moved the workshop to a new location, 17 rue Campagne-Première, which inspired the name by which the studio would be known: Atelier 17.»

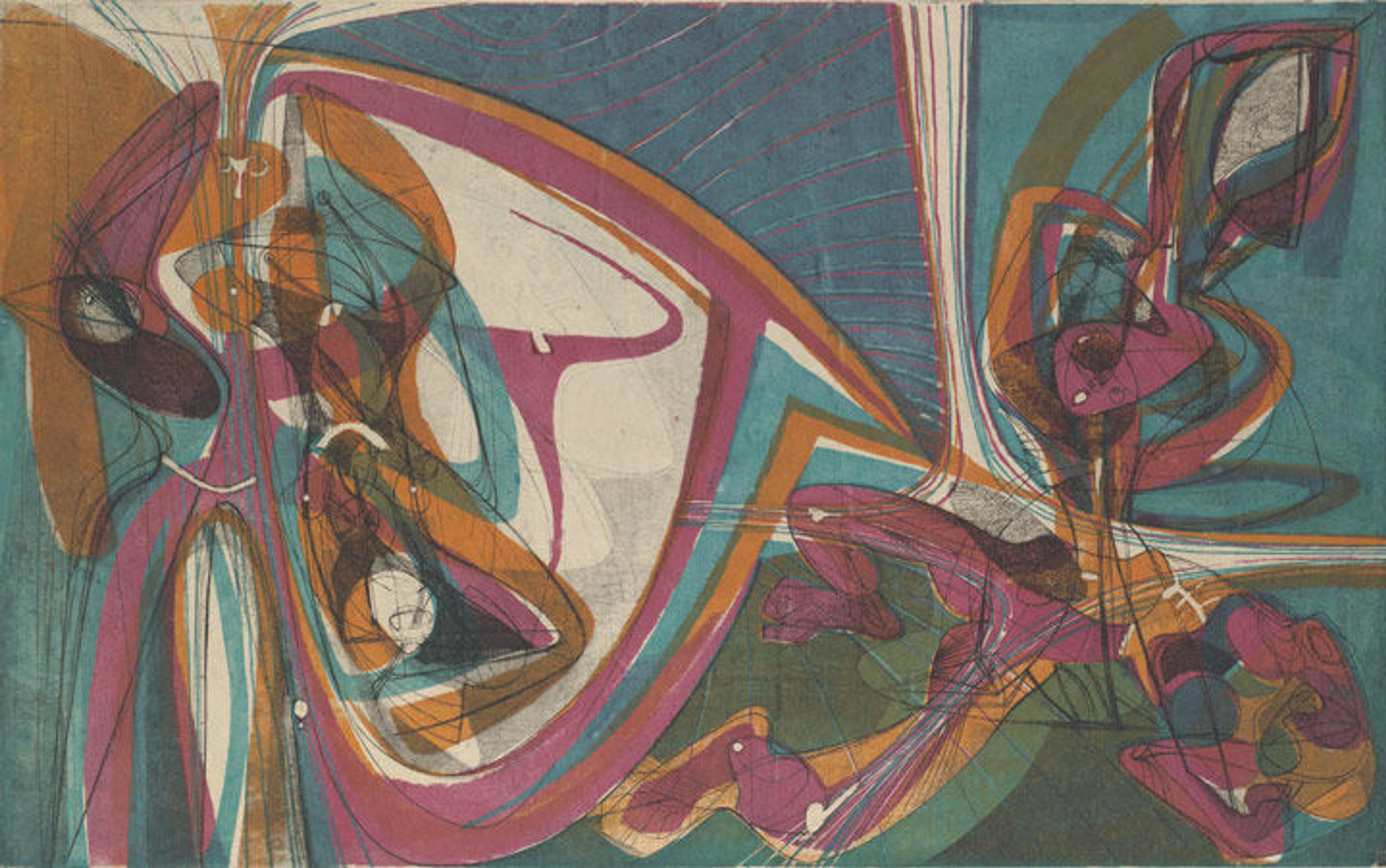

Hayter fostered a collaborative atmosphere at Atelier 17; techniques, imagery, and methods were freely shared by artists who influenced each other and worked together to advance printmaking. Hayter and the artists of Atelier 17 revived intaglio techniques (etching, engraving, and drypoint), developed new methods (such as soft-ground etching and color viscosity, also known as simultaneous color printing), and incorporated practices from movements such as Surrealism—namely psychic automatism, the belief that the artist's unconscious mind could guide his or her hand across the metal plate to reveal an image developed without conscious thought, intentionality, or preliminary drafts.

Eschewing concepts of authorship and the traditional hierarchical relationship between teacher and student, Hayter intended for Atelier 17 to be a space marked by collaboration and the free exchange of ideas. His goal was to create a kind of laboratory in which people with varying levels of experience and different approaches to the medium might experiment and develop new printmaking techniques. Hayter explained the working method and the philosophy that guided the workshop in a 1971 interview conducted by Paul Cummings for the Archives of American Art, in which he stated:

The way we work, there is no sort of professor and student deal going on here. . . . I have always had the theory since I started this thing that if you are going to get anything done about this craft it is going to take a lot of people to do it and you have got to work with them, which means a damn sight more than it sounds because there are hardly any cases of it being done. . . . You have got to put yourself on the level of the last beginner and keep in your mind the fact that with you too this is extremely tentative. That's to say, you can look at a plate every day that you go to work with a lot of people as if you had never seen a plate before.

It is a very difficult thing to do because you have got to shake yourself up now, and then say: Listen, you think you know something about this, it isn't true you see . . . and you must of course have no personal vanity whatever when you're playing this game.

Stanley William Hayter (British, 1901–1988). Cinq Personnages, 1946. Engraving and soft-ground etching; simultaneous color printing with stencils, 14 15/16 x 24 in. (37.9 x 61 cm), Sheet: 20 1/8 x 23 3/16 in. (51.1 x 58.9 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Paul F. Walter, 1980 (1980.1117.1) © 2016 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Hayter left Paris in 1939 and moved to London, where he developed camouflage techniques for the British army. After leaving Europe for the United States in 1940, he ran Atelier 17 in New York City for 10 years, in connection with the New School for Social Research, before returning to Paris and reestablishing the studio.

At each iteration of the workshop, Atelier 17 provided a stimulating environment both for established artists and more emerging figures to experiment. When it opened in Paris, the workshop was dominated by Surrealists such as Joan Miró, André Masson, and Max Ernst; in New York, Atelier 17 was where European émigrés connected with artists who would soon be associated with the New York School, including Louise Bourgeois, Robert Motherwell, Louise Nevelson, and Jackson Pollock, showing how Atelier 17 was instrumental in the development of gestural abstraction in America.

The studio was the most global, however, after it reopened in Paris in 1950, when it began to attract artists from around the world, including the Indian-American artists Krishna Reddy (born 1925) and Zarina Hashmi (born 1937), who used this fertile ground to evolve their styles and techniques. Reflecting a postwar cosmopolitanism, artists such as Krishna and Zarina brought new aesthetic sensibilities and methods, as well as their cultural history, much of which was relatively unknown in postwar Paris, and which, in turn, influenced artists at Atelier 17 and their contemporaries in Paris.

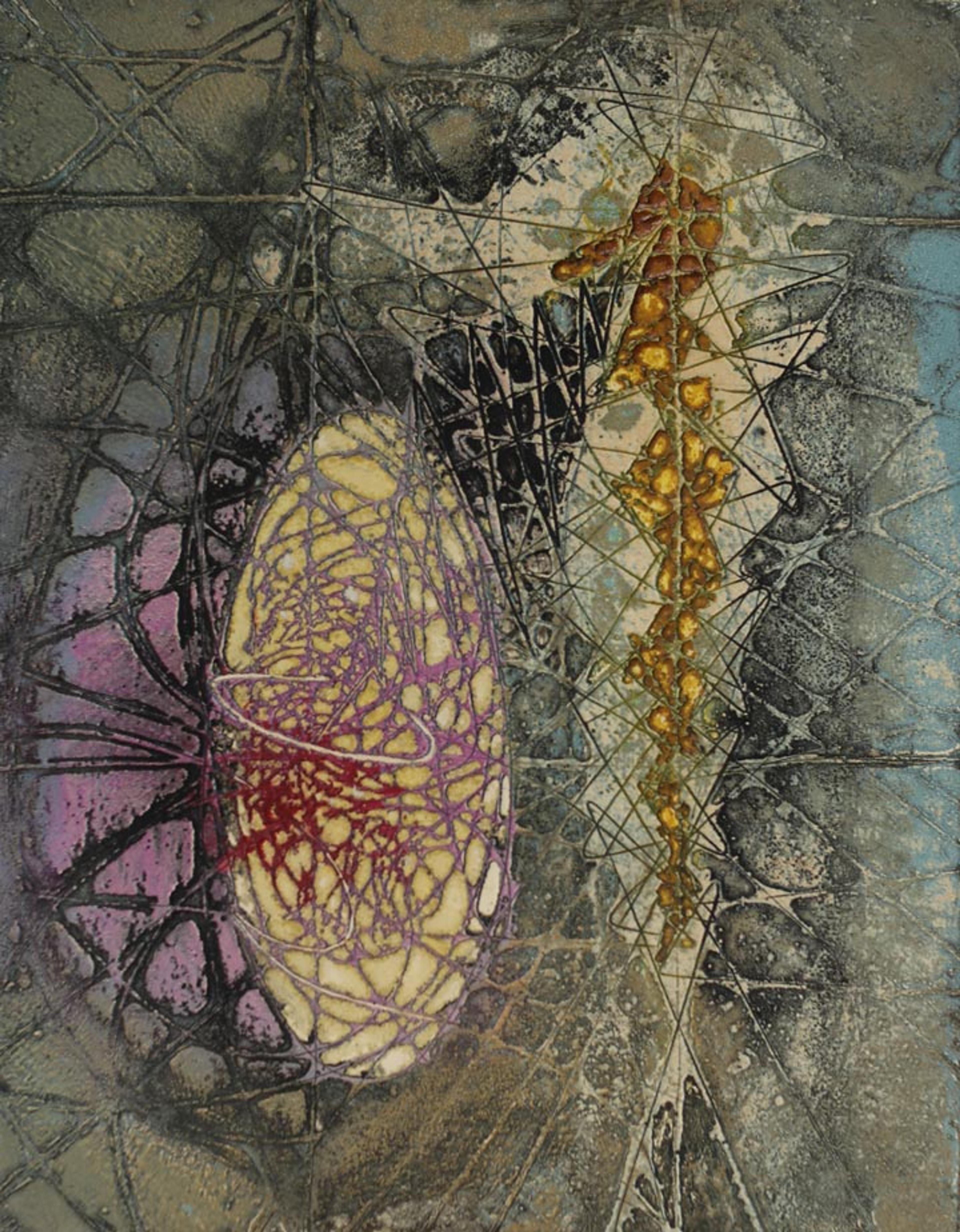

Central to the philosophy of Atelier 17 was a desire to challenge the belief that printmaking was merely a "reproductive" art; led by Hayter, the artists showed how printmaking contained a field of creative possibilities, all of which could be expanded through the viscosity method. Krishna Reddy, who had a background in sculpture before he turned to printmaking, viewed the plate not merely as a tool or component for printmaking, but rather as a work of art in its own right.

Working together at Atelier 17, Hayter and Krishna (who was the co-director of the workshop from 1964 to 1976), referred to their backgrounds as a scientist and a sculptor, respectively, to make groundbreaking advances in simultaneous color printing. In this process, a metal plate (generally copper) is incised with numerous grooves of staggered depths and textures that operate in tandem with inks composed of different oils applied with both hard and soft rollers. The various weights of the inks and pressures from the rollers allow several colors to be applied directly to an etched or engraved plate and then printed in one pass, or movement, through the press, to produce a multicolored print, each of which will display small variations. Because of his experience with sculpture, Krishna viewed the shimmering copper plates incised with the various grooves and marks of the viscosity method not merely as tools or components for printmaking, but rather as works of art themselves.

Krishna Reddy (American, born India, born 1925). Bull & Man, 1954. Etching impressed by the artist (2/10), Height: 26 in. (66 cm), Width: 20 in. (50.8 cm). On loan from the artist

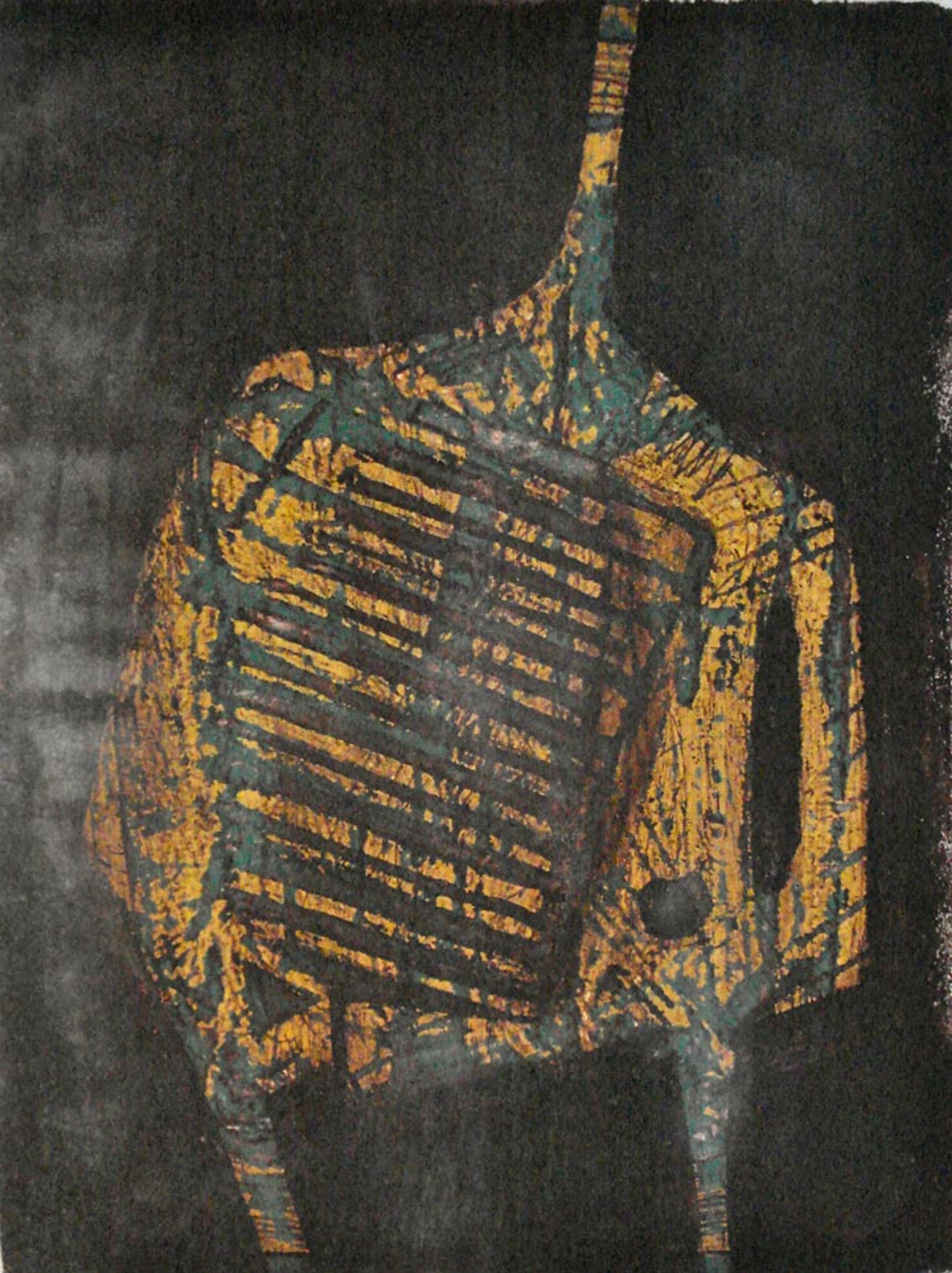

It was also at Atelier 17 where Zarina first embraced printmaking and developed an interest in handmade paper. Between 1964 and 1967, she learned intaglio methods at the workshop. Like Krishna, Zarina often combined abstract patterns with representational elements in work from this period. However, while Krishna's art evoked the organic world, Zarina's dark palette and subjects referred more to the spaces and issues shaping contemporary urban life.

The haunting image of a single figure, scarred and naked, in Man, for instance, shows the influence of existentialism while also evoking the brutal legacy of war and the colonial oppression felt in India during English rule. The print's scratched surfaces, layered patterns and colors, and textural effects evoke the illegal markings of graffiti, as well as the art brut pieces the French artist Jean Dubuffet (1901–1985) developed in the wake of the Second World War. Zarina later traveled back to India and to Japan, where she continued to explore new printmaking methods and ways to engage the distinctive qualities of handmade paper.

Zarina (American, born Aligarh, India, 1937). Man, undated. Etching (viscosity). On loan from Zarina

The dialogic space of Atelier 17 represented a particularly radical departure from the traditional workshop structure within which artists of India and the Muslim world had worked for centuries. Krishna, Zarina, and the numerous artists who passed through Atelier 17 found an environment that provided the materials and support necessary to advance the possibilities for printmaking and for modern art broadly considered.

As Zarina later said, working with Hayter and at Atelier 17 "freed" her, as it exposed her to a variety of new ideas and approaches in addition to giving her the confidence to follow her own vision and to create unique and powerful works. This is just one example that shows how Hayter's radical redefinition of the workshop model at Atelier 17 expanded possibilities for printmaking and continues to be felt today.

Related Links

Workshop and Legacy: Stanley William Hayter, Krishna Reddy, Zarina Hashmi, on view at The Met Fifth Avenue through March 26, 2017

RumiNations: "Krishna Reddy and Atelier 17: A 'New Form' Takes Shape" (October 18, 2016)

Jennifer Farrell

Jennifer Farrell is a curator in the Department of Drawings and Prints.